Five years after the Sri Lankan Army killed the Tamil Tiger leader, his most ardent supporters refuse to believe Velupillai Prabhakaran is dead.

On May 18, 2009, the Sri Lankan Army killed the Tamil Tiger separatist leader Velupillai Prabhakaran. The cause of death was believed to be a single shot to the head at close range. The army had two former Prabhakaran allies turned government mercenaries visually ID the body; they also took a DNA sample. Then they cremated him.

With Prabhakaran’s death, the bloody 26-year Sri Lankan civil war came to an abrupt end. But the peace since has been deeply uneasy. Sri Lanka’s Tamil heartland, the north and east parts of the South Asian island, has been “pacified” at great human cost, with the Sri Lankan army occupying large swaths of land. The military also controls much of the economy—from grocery stores to hotels. In Tamil areas, locals rarely leave their homes after dark for fear of harassment or sexual assault from Sri Lankan soldiers.

Five years after the end of the war, many Tamils believe they have received neither a true home nor justice. In my travels around the region and through the global Tamil diaspora, I have found that for many people, that existential angst has resulted in one very peculiar question: is Velupillai Prabhakaran really dead?

You don’t have to look hard to find skeptics. On YouTube, loyalists, conspiracy theorists, and self-styled investigative journalists post videos, often set to dramatic soundtracks, that pick apart government footage of Prabhakaran’s body. I’ve heard the doubts whispered by everyone from Tamil exile leaders in Toronto to the Tamil restaurateur in neighborhood in Brooklyn.

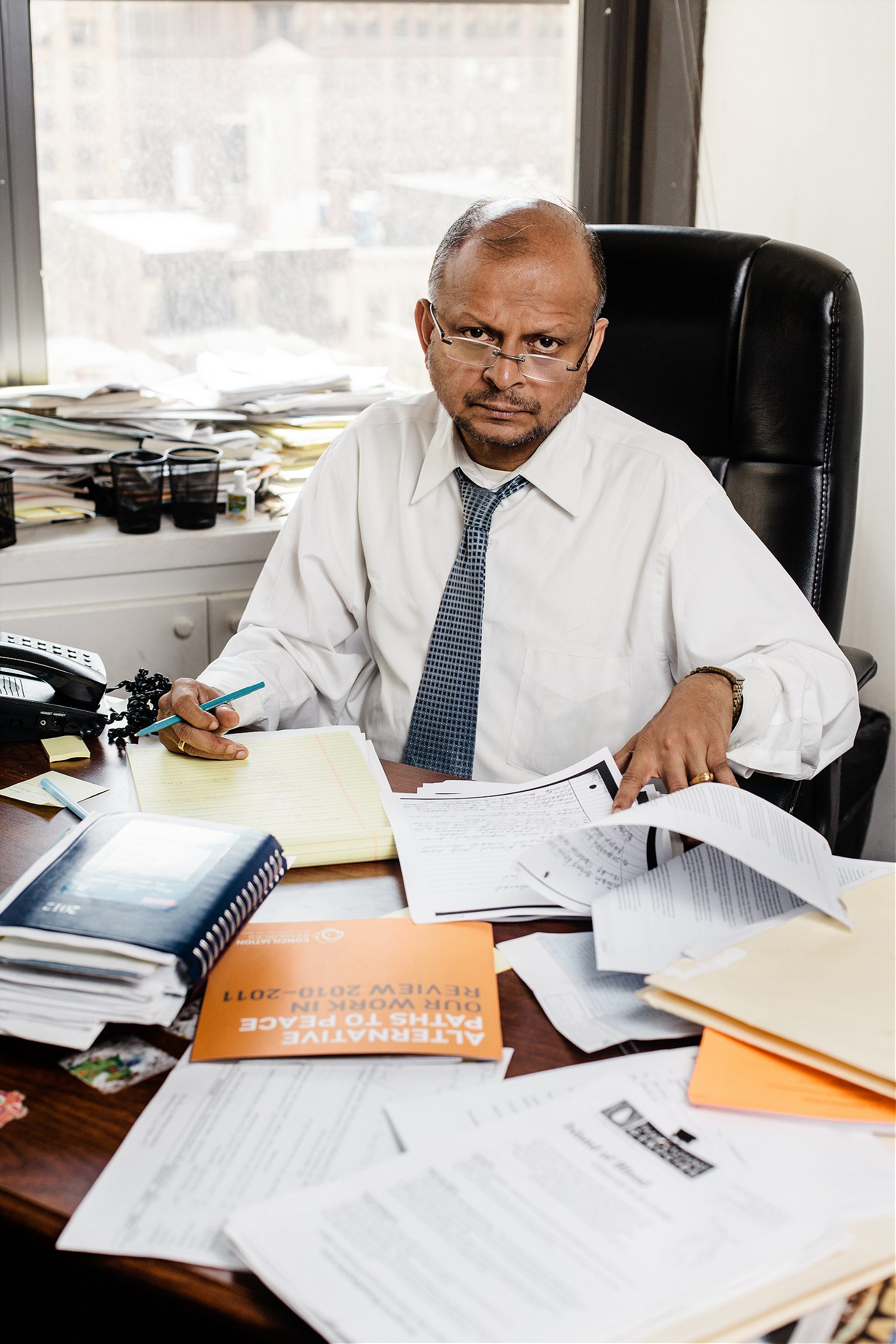

It’s a view championed by people you’d assume would know better. People like Visuvanathan Rudrakumaran, a fierce orator and defender of the Tamil cause who also runs the Transnational Government of Tamil Eelam (TGTE), a government in exile committed to achieving Tamil independence through peaceful means. Over the years, the two of us have lunched together at our favorite Chettinad restaurant in Manhattan. One day, he admitted something remarkable: until he sees Prabhakaran’s body in person, he remains unconvinced the separatist leader is dead.

To Samanth Subramanian, a New Yorker contributor whose book, This Divided Island: Stories from the Sri Lankan War, explores the conflict in depth, this suspicion has its own logic. “Part of the reason people may think Prabhakaran is still alive lies in his own life—in the way he repeatedly got himself and the Tigers out of tight situations during the war, and in the way he was so difficult to capture,” he says. “Another reason is the way he was finally captured and killed—in circumstances that were murky, and in front of unreliable witnesses, like soldiers.” These doubts are compounded by the “continuing difficulties of Sri Lankan Tamils, who still fell under threat from the state,” Subramanian adds. “[They] yearn for a champion.”

The Tigers are credited with popularizing suicide bombing and creating the suicide vest

For close to thirty years, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam ran the world’s most well-branded insurgency. Their iconic flag featured a snarling Tiger set against a blood red background centered within two crossed rifles and a ring of bullets. Prabhakaran, who was rarely seen and was known to use body doubles, added to the mystique. After training in Lebanon with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, he adopted founder George Habash’s philosophy that a dead civilian is worth 100 dead soldiers. The Tigers are credited with popularizing suicide bombing and creating the suicide vest. Between 1983 and 2009, the organization killed more than 1,000 people in suicide bomb attacks.

Though he was ruthless and often terrorized his own community, many Tamils saw Prabhakaran’s violence as their last hope. Sri Lanka’s conflict pitted the majority Sinhalese community against the Tamil minority who’ve traditionally lived on the island’s north and east coasts, across the Palk Strait from their linguistic cousins in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. At the beginning of the war, the Tigers enjoyed the patronage of India’s intelligence service, which set up training camps in India.

But by 1987, as the Tigers grew bolder and more violent, the Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi switched sides, dispatching the Indian Army into northern Sri Lanka to aid the Sri Lankan Army. The Tigers, masters of asymmetrical warfare, routed them. In 1991, still angry with Gandhi, Prabhakaran retaliated inside India. As he appeared at a small city called Sriperumbudur, near Chennai, the Tigers sent three suicide bombers to put a garland filled with explosives around the Gandhi’s neck. The explosion killed the Prime Minister and 18 others. Hundreds were wounded.

Prabhakharan, like Che Guevara, is often perceived as less a terrorist than a folk hero

More than 20 years later, many young people don’t remember the full extent of the Tigers’ reign of terror. And Prabhakharan, like Che Guevara, is often perceived as less a terrorist than a folk hero. Prabhakaran’s likeness appears on murals, political posters, and anywhere where local politicians from all stripes can borrow his political capital and his cult of personality for votes.

To three young privileged political insiders I met at a bar in Coimbatore, in India’s Tamil Nadu, who carried pictures of Chief Minister J. Jayalalithaa in their breast pockets, Prabhakaran was a strong man like Narendra Modi, India’s newly elected prime minister. My driver, who had endured a childhood of violence and watched his father kill his baby sister with his hands, identified with Prabhakaran’s hardscrabble upbringing. Prabhakaran emerged from a poor lower-caste background to create a caste and sex-blind fighting force in the Tigers, a point underscored by an elite female suicide squad who wore cyanide capsules around their neck to swallow in case of their capture and was responsible for killing Gandhi.

Even in Sriperumbudur, where the Tigers murdered Gandhi, a man I met named David who had been maimed in the explosion and now walked with a cane, said he still supported Prabhakaran and believed in his cause.

**

Toronto boasts the world’s largest Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora, an estimated 250,000 people. If you ask people there, they will often tell you that Prabhakaran is merely in hiding and will re-emerge to lead the struggle for Tamil Eelam. In Scarborough, a Toronto suburb and the heart of city’s Tamil community, images of Eelam and Prabhakaran were visible on the front glass of every small Tamil supermarket, restaurant, and small business.

The de-facto Canadian consulate for the de-facto state of Tamil Eelam is an insurance agency/mortgage brokerage above a Jamaican beef patty joint in a workaday Toronto strip mall. There, I met with three members of the Transnational Government of Tamil Eelam: Deputy Prime Minister Dr. Ram Sivalingam, Sam Sangarisivam, and Secretary of Information Roy Wignarajah.

Wijnarajah, who sells life insurance out of the office, had secured the conference room for our meeting. Like most of the community, he’d found his way to Canada after Black July, when Sinhalese mobs killed more than 3,000 people. With its relatively open immigration policies, job opportunity, and strong social safety net, Canada became a haven for Sri Lanka’s Tamils.

“The apartment building that I was living in was attacked in Colombo,” Wignarajah said. “The person who was leading the mob was a Buddhist priest in robes with the election voters list. And he was pointing every Tamil house. They had the voters list!”

Like Rudra, the three men seemed unable to wrestle with some of the truly horrific things of which the Tigers have been accused, not least of which was a 2006 Human Rights Watch report that found their proxies were extorting Tamil businesses in Toronto for donations.

They are most comfortable talking about the harsh realities for Tamils still inside Sri Lanka. “It is like an open prison,” said Sangarisavam, over donuts and coffee at a local Tim Hortons. “Everyone is under the control and there’s no way you can go and complain or you can even say anything against them. If you do, you will disappear next day.”

The Sri Lankan government has portrayed the victory over the Tigers as yet another battle in the War on Terror

Since the end of the war, the Sri Lankan government has refused to acknowledge the well-document discrimination faced by Tamils after Sri Lanka’s independence, which precipitated the war in 1983. Instead, it has portrayed the victory over the Tigers as yet another battle in the War on Terror. “We are the only country that defeated a terrorist group comprehensively,” UN Ambassador Palitha Kohona told me at his office on Manhattan’s east side. “The LTTE were a bunch of thugs.” Kohoona dismissed the idea of Tamil statehood. “This myth of a homeland is never going to happen because it was never there to begin with,” he said.

The more time I spent with Kohoona, the more I understood the diaspora’s nostalgia for Prabhakaran. Five years after the war’s end, Sri Lanka’s ruling Rajapaksa family has consolidated power, watered down the judiciary, crushed dissent, and allegedly murdered political rivals.

When I asked Kohoona about a wealthy Montreal-based Tamil named Andrew Antonipillai Mahendrarajah, who had travelled to Sri Lanka in May 2012 to reclaim land the army had allegedly grabbed and was castrated and murdered, he seemed to play dumb: “I actually don’t know anything about this case so I couldn’t answer any questions.”

I pressed him on the story, sharing some widely reported details of the case. “I don’t know a thing about this story,” he said. “Some story about the military killing people”—his voice rose an octave to convey an exaggerated sense of disbelief—“because he wants his property back, it has to be looked at with a little bit of care.” (The case has been cited by foreign governments and rights groups as an example of Sri Lanka’s continuing culture of impunity.)

Kohoona returned to his talking points, reiterating the official policy that government forces freed the Tamils from the grip of a vicious terrorist force that controlled the Jaffna Peninsula against their will. “The only facts that are known to the world, and I am going to repeat them, is that we are the only country that defeated a terrorist group, comprehensively.”

Since the end of the civil war, Sri Lanka has continued to be hostile to minorities

The government, he explains, is committed to making Sri Lanka a harmonious society. “It’s time that we forgot the bitterness of the past and got on with life because life gives you a second chance sometimes,” he said. “And this is a second chance we have and we must use it so that the next generation doesn’t suffer.”

But since the end of the civil war, Sri Lanka has continued to be hostile to minorities. Over the last year, radical Buddhist groups have led attacks on Sinhalese Christians in the South and Muslims in the east. The army occupies most of the north and east of Sri Lanka, the notional Eelam once controlled by the Tigers. Human Rights Watch’s 2013 wrap-up was titled Sri Lanka: Little Progress on Rights.

May 19 marks the 5th anniversary of the end of Sri Lanka’s civil war. On March 27, Rudra and other Tamil activists in the diaspora finally succeeded in pushing the UN Human Rights council to investigate rights violations and war crimes committed during the final days of conflict by both the Tigers and government forces.

In response, the Rajapaksa government branded the TGTE, Rudra, and hundreds of other groups and individuals as foreign terrorist organizations. Rudra laughed wryly about the move. “Even if you don’t believe in an independent state,” Rudra told me, “if you want to have reconciliation, this is not the way to do it.”

In the lead-up to the anniversary this week, Rudra and other activists picketed the UN trying to force Sri Lanka to reconsider their prohibition of separatism. But on the Sunday before the anniversary, Rudra and other TGTE members instead planned to gather quietly in Queens and hold a memorial for the 40,000 people who died in the final battle—including Prabhakaran, the man Rudra and others still hope isn’t dead at all.