A writer journeys to the Louisiana backcountry looking for the legend of America’s outlaw couple.

I’ve always wondered why certain histories morph into myths and legends. What is it about a Butch Cassidy or a John Dillinger that captures the imagination? Part of it might be our childlike fascination with outlaws, those individuals on the edges of society who flout the norms that bind the rest of us. In some respects, it may be our love for those who take what they do not have; but even so, there has to be a measure of elusiveness involved. The outlaw must be crafty, display cunning, and a cat-and-mouse game must ensue. The stories have to entangle our minds and ensnare our judgments. Time has to bleed away. And if all the right pieces fall in place, eventually, we might find ourselves standing in historical escapism.

Bonnie and Clyde first came into my consciousness about the time I realized black-and-white TV shows were byproducts of technological deficiencies rather than earthly deficiencies—the world, to my amazement, had always been in color. But at a very young age this was hard to understand. History, for me, was black and white, good or bad, right and wrong. On Sunday afternoons my family would have post-church lunch at my grandmother’s house, and much of the time was spent in my uncle’s childhood room, which time seemed to have preserved in formaldehyde. On the bookshelves sat metal figurines of cowboys, and Indians, and war. Model bombers hung from the ceiling. And tacked to the wall were two wooden placards emblazoned with the black-and-white wanted posters for Billy the Kid and Jesse James. Wanted, they both said. Dead or Alive.

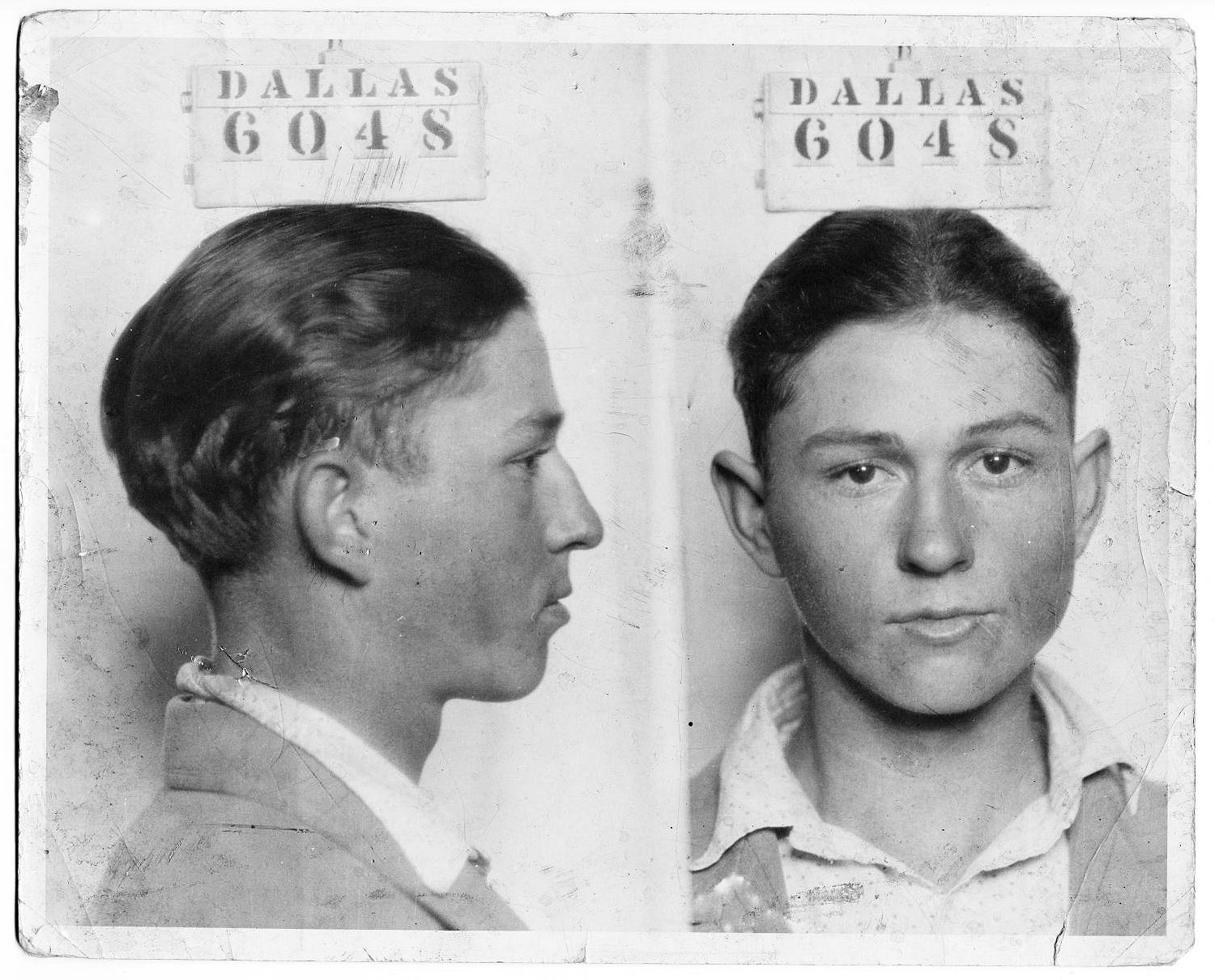

Through the years I came to share my uncle’s fascination with the American outlaw, and as my fascination grew, the American outlaw transformed from rambling train robber to Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in Technicolor. When I was around twelve, my uncle drove me to the Clyde Barrow gravesite on Fort Worth Avenue in Dallas. A billboard stood at the southwest end of Western Heights Cemetery and shaded the grave. A cheap motel and a small used car lot were within eyesight. It was hard to believe the Clyde Barrow was buried there, especially when cars geared by. Such a mountainous figure confined to such a small, isolated space. History covered by the advancements of time. The inscription on the grave reads: Gone but not forgotten.

The rain beats down on the roof of my car as I see the exit for Gibsland, Louisiana, turn off of U.S. 80, and head south. I’m researching Bonnie and Clyde for an article, and the small town of Gibsland is ground zero for Bonnie and Clyde enthusiasts. It’s the last outpost of living information and home to the Ambush Museum. Eight miles south, where they were gunned-down in a hail of bullets, stands a stone marker.

The road eventually turns into Main Street, Gibsland’s one thoroughfare. It’s a spittle of a town. Back in the day, briefly, the town was known as a railway junction and home to Coleman College, but all I can see through the torrent is the overgrown green trappings of Louisiana backcountry and the foundation of a former home. I slow down to cross over some railroad tracks and see a small row of buildings in the distance. It looks like nothing civilized has lived here for decades.

As I come up the middle of Main Street, I realize the town is nothing more than a block of storefronts that face one another. The most visible sign reveals itself in yellow above a flat, green metal awning. I see the word Ambush in big letters. In front is one car by itself, a gray, late-80s suburban parked combat-style, backed in tail-first, ready for a quick exit.

I had done some online research for the trip and found a Facebook page for the Bonnie and Clyde Ambush Museum. I found the name of L. J. “Boots” Hinton, the museum’s curator, and called the phone number. Over the next three days I called three more times and left messages asking if I could meet with Boots and speak about the ambush. I left my number.

Eventually I became concerned when I read on the Facebook page that the museum had been closing intermittently due to Boots’ health concerns. When Friday afternoon rolled around and there was no reply, I decided to book a hotel room in Shreveport, Louisiana, anyway and headed down that evening. In total I would travel the three-and-a-half hours from Dallas, where I live, not knowing what I’d find.

I have my girlfriend with me in hopes of doubling the trip as a getaway, but as we sit in the car staring at the fogged windows of the museum, she says, “We came for this? I can’t even see anything.” I shake my head—it would be hard to just stumble across a place like this. The storefront is the only one with a light on. I give her the umbrella and, before we jump out, she says, “It looks open, right?”

A bell rings as we enter and inside we find a small anteroom that doubles as a makeshift office/cashier space and a sparse gift shop. There are a few t-shirts and a few books for sale. Off to the left sits a man in what looks like a flame-retardant flight suit—black—with a fur collar and a baseball cap that says “Navy” on his head. He’s wearing round, wire-framed glasses and has his legs crossed. He looks up at me and takes a drag from a cigarette. And when he doesn’t say anything, I’m not sure if he actually sees me at all.

“Video just started,” he mumbles. “Go on in.” The door says, “No Photography,” and I’m standing there with a borrowed Nikon around my neck.

When I push the door open it wiggles a bit with a flimsy reverb and I realize the anteroom isn’t completely separate from the main museum room. The wall doesn’t completely touch the ceiling; it looks like a large cubicle.

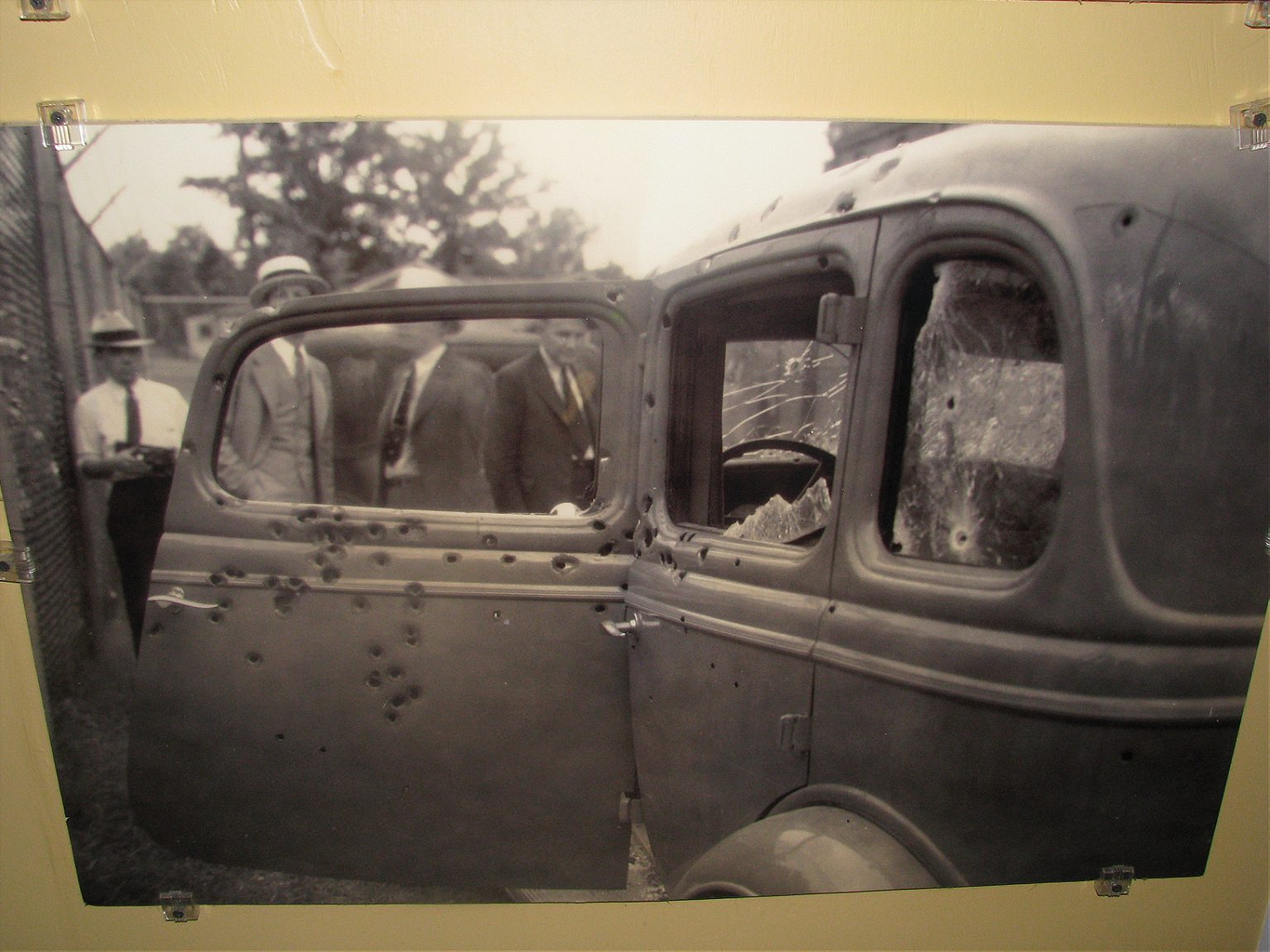

Inside and off to the right four people are sitting in chairs you might find in the carpeted rec/banquet room of a Church of Christ—I must have missed the other two cars somewhere in the rain. I sit down and start trying to process everything: the Bonnie Parker movie poster starring Dorothy Provine (Tagline: Cigar Smoking Hellcat of the Roaring Thirties); the glass cases full of Bonnie and Clyde comic books, postcards, books, even a restaurant menu. And on a small table pushed against one wall sits a tiny Panasonic TV with a built-in tape player. The video runs for a few minutes and shows grainy black-and-white video of the couple’s death car. It’s silent. A plastic bucket in the middle of the room collects a steady drip of rainwater.

When the video is over we begin walking around the small museum, which is approximately the size of large loft apartment, depending on which city you’re in. On one wall is a timeline of the Bonnie and Clyde story, from Clyde’s birthplace of Telico, Texas, to the predestined ending, a topic that’s heavily themed here. Slowly strolling past the information, I discover things I’d never known, or had at one point read and pushed out of my mind for the sake of maintaining a certain rose-colored image.

At one point I read that Clyde had a heart-and-dagger tattoo. Something about it doesn’t fit with the Clyde I know and the picture I hold. All I can see in my mind is a cartoonish red heart on the wall of a tattoo parlor in Dallas. I learn more about the small group of members that constituted the gang. Over a short period of time, by their own hands or those of the police, the Barrow gang’s bodies were chipped away at like marble. A finger here, a toe there. The literature makes it sound more like a desperate attempt at survival than the story of Romeo and Juliet on a semi-heroic, love-drunk robbing spree.

I do a few more circles around the museum. Against another wall are photos of the death scene and the ensuing days (two bodies slumped over in a stolen Ford V-8, each riddled by various-sized shells, both covered in blood; the bodies eventually laid out in a morgue and covered somewhat with white sheets). At the back of the museum is a replica of the death car, though it has fake bullet holes and stands in as a poor substitute. A single-toilet-bathroom is directly next to it. I can’t help but wonder how this place stacks up to the other shrines of the world.

I walk back out to the anteroom as the last two people are leaving. The man in the flight suit is leaning over and ashing his cigarette in one of those empty Starbucks Frappuccino bottles they sell at gas stations.

“Are you Boots?” I say.

He looks up at me and nods.

I give Boots my name and he stares at me for a while.

“A Cameron from the Dallas Morning News is coming down here today to interview me,” he says, taking another drag of his cigarette.

I have no doubt that someone else is looking for a story from Boots, but I doubt there’s a reporter from the Dallas Morning News with my name that’s coming down on the same day, and it’s certainly not me, because I don’t work for them.

Boots tells me that he is the son of former Dallas Deputy Sheriff Ted Hinton, one of the men that opened fire during the ambush on May 23, 1934, not long after the pair drove away from the Ma Canfield’s Café, which is actually the same storefront as the Ambush Museum today. He begins a whirlwind story that has bits and details that only the son of someone involved in the history would know. It turns out at least one of the posse members sent to hunt down the lovebirds turned to alcoholism afterwards.

“You ever been in a firefight?” he asks.

From the look of me the answer should seem fairly obvious.

“It’s like being in hell,” he says. “He had the PTSD. But they didn’t have a name for it in those days.”

He starts in on long retellings of the events and drifts off, losing his train of thought. At one point he notices a dripping noise behind him, slowly turns, and just stares at a stack of notebooks for a while. The history seems trapped inside him at times, only leaking out slowly like the rainwater. He’ll lull himself into a quiet place, and when I start to talk, he begins another story.

The cigarette burns down, ash falls on his flight suit. He places it in the Starbucks bottle and lights another one. “If you’ve ever tried to drive a ’34 V-8…” he trails off. And this goes on for an hour and a half.

By the end we’ve exhausted the history of Bonnie and Clyde—what they ate, where they went, who was looking for them. He even tells me that his dad and a man named Bob Alcorn passed them once during the manhunt when they were on Shoefly Road, which, it turns out, is actually a type of road meaning bypass, and is actually spelled “shoofly.” This is my mistake. Boots hands me a flyer and tells me to come back for the 80th anniversary festival at the end of May.

He lights another cigarette. The bell rings.

I want to see what a festival for two killers who were blown away in the most spectacular way imaginable could possibly be like

On my return trip I arrive at the festival early. I’ve already completed the research I need, but I want to see what a festival for two killers who were blown away in the most spectacular way imaginable could possibly be like. That, and I want to see Boots again. As I pull up there’s a markedly different look to the place. The sun is out. Cars are lined around a field and a few people are walking towards the Ambush Museum. My girlfriend grabs the gin bucket we concocted for the occasion and we head towards the show.

People are standing and sitting up and down the curb of Main Street. To the left of the Ambush Museum, in a building detached from the rest, there’s another storefront claiming to be dedicated to Bonnie and Clyde, but after a quick walk through, it turns out to be nothing more than a few rooms with newspaper clippings and kitschy stuff. I buy a refrigerator magnet in the shape of an old-timey car that says “Bonnie and Clyde Ambush. 80th Anniversary. Gibsland, LA.” When I step outside, I regret not getting the coffee mug.

Across from the Ambush Museum people are loitering around a trailer which has been converted into a smoker and grill. A voice comes over a PA system and in front of the town hall is an older man with a jet-black-dyed comb-over. He’s dressed as an Elvis impersonator and he breaks into one of the greatest hits. “I don’t associate Bonnie and Clyde with Elvis right away,” my girlfriend says, toting the gin bucket around like well water. “Just…not immediately.”

“Sure,” I say. “But not immediately.”

An hour later a reenactment of a Bonnie and Clyde bank robbery begins. This is one of the highlights, and very similar to two others I’ve seen in person, both in Texas. A non-descript man wearing ‘30s attire runs out of the local bank followed by a woman in a red dress and beret. Four or five men who are dressed liked ‘30s sheriffs and deputies and have been taking pictures with people and shaking kids’ hands jump to attention. All parties raise their firearms.

After a moment of scripted shouting, blanks begin to pop and crackle throughout Main Street. A sheriff goes down. Bonnie drops her bag and runs back to grab it. Car doors fly open, men drop to their knees for accuracy, and smoke fills the street. People are clapping and a child is waving an American flag.

We’re told the parade will begin in an hour and a half, but before that there’ll be a Bonnie and Clyde lookalike contest. Fifty bucks will be awarded to the adult winner and 25 in the kids’ category. We set off to find a place in the field to put our blanket down and have a drink in the shade. As we walk across the street, I notice a corrugated mobile home in the distance with large plumes of smoke drifting out from behind it.

“What is it?” my girlfriend says.

“I think it’s food. You want anything?”

She shrugs.

I walk over and there’s a barbeque menu tacked next to an open window with bars behind it. I look around, wait a few minutes, and when no one shows, I walk around to the back. Two guys are there, one manning a giant drum grill, the other sitting on a foldout chair.

“You guys have any barbeque?” I say.

One man smiles; the other shouts towards the trailer.

The ribs are covered in a sweet, sticky sauce, and the meat sheds off the bones and crumbles like pulled pork. The rack goes down in record time. I’ve had ribs across Texas, North Carolina, Kansas City, and anywhere I can find in between. I won’t stake my life on it. There’s undoubtedly something about the place. It could even be the gin. But they are the best ribs I’ve ever tasted, and I walk back for two more Styrofoam lunch containers. When I get there, no one seems surprised to see me.

We sit there for what seems like a long time. Two wild dogs that have been inching closer to us for a while finally realize we’ve eaten all the food and move on in another direction. A black gentleman in a wide-brimmed hat slowly saunters by on an emaciated looking white horse. The parade begins and you can hear motorcycles revving in the distance. Children stand up from the curbs and the small parade starts to filter down Main Street before making a left turn right in front of us and heading past the field.

There are a couple of old-timey cars that go by. A family of four, each one on their own four-wheeler. Finally, an old convertible passes with Boots sitting like a flagpole in the back. He has on a white cowboy hat and is wearing a checkered dress shirt. For the most part he looks straight ahead, but he waves occasionally, like a king passing his subjects.

The final car rolls on past and the PA system comes back on. The final event will be held in a few hours at the ambush site eight miles away. It feels like both the main performance and the curtain call.

“Do you want to stick around for that?” my girlfriend says.

As I sit there I can’t help but think of the stories my uncle shared with me, how he talked about Bonnie and Clyde with such reverence. Yes, they were bad, but they were also mythical. The robberies, the shootouts, the escapes—they all seemed so heroic in a way that knowingly distorts reality. I can’t imagine Boots seeing any heroism in it, except for maybe his father and the other men, but even that, the way he told it, sounded like a curse. The way history has blurred the events actually bothers me, and what was once a childhood fantasy seems grayed by adulthood, like most things. I can’t even explain it. People died. Citizens around the country were struggling to survive. And the story of a young man and women who were blown away in their car has a nostalgic place in American lore.

Finally I imagine what it would be like if it happened today, and wonder why people have driven by the roadside marker over the years and pockmarked it with bullets. Is it a form of flattery or condemnation, and where does this festival fit in between?

My girlfriend asks me again. “No,” I say. “I can imagine it.”

When the anniversary came back around this year, I went online and looked up the Ambush Museum’s Facebook page just to see what was going on. It said a new owner had taken over the establishment and expanded the merchandise in the museum’s gift shop. There was a recent picture of Boots in black jeans and what looked like a pressed tuxedo shirt. And under the “PEOPLE ALSO LIKE” category were Vintage Camper Trailers and Dawn Wells, who was Mary Ann on Gilligan’s Island.

I googled Clyde Barrow one last time, just for the hell of it, and realized he doesn’t even have his own Wikipedia page. There’s only one for the duo, Bonnie and Clyde. Some things just can’t be separated.