In Myanmar’s Kachin State, the jade industry funds conflict, drugs and corruption.

Stretched across the northern mountains of Myanmar, Kachin State is the jade mining capital of the world. A single stone, once cut and processed for the international market, can sell for several million dollars. But although the industry comprises nearly half of the country’s GDP, at around $31 billion annually, it hasn’t done much to lift Myanmar from the bottom ranks of the world poverty index.

In the region dubbed the “new wild west of Asia,” control of ore is one of the issues contributing to the world’s oldest civil war. It started when ethnic Kachin rebels took up arms against the national government after a military coup in 1962. Due to its remote location and strict travel restrictions imposed by the government, the international community has largely ignored the conflict. Today, Kachin State is part of a lawless grey area, controlled in patches by the national government, rebels and local militias (read R&K’s 2012 interview with the daughter of Kachin freedom fighter). The lucrative jade trade plays a key role in keeping the conflict alive and well-funded.

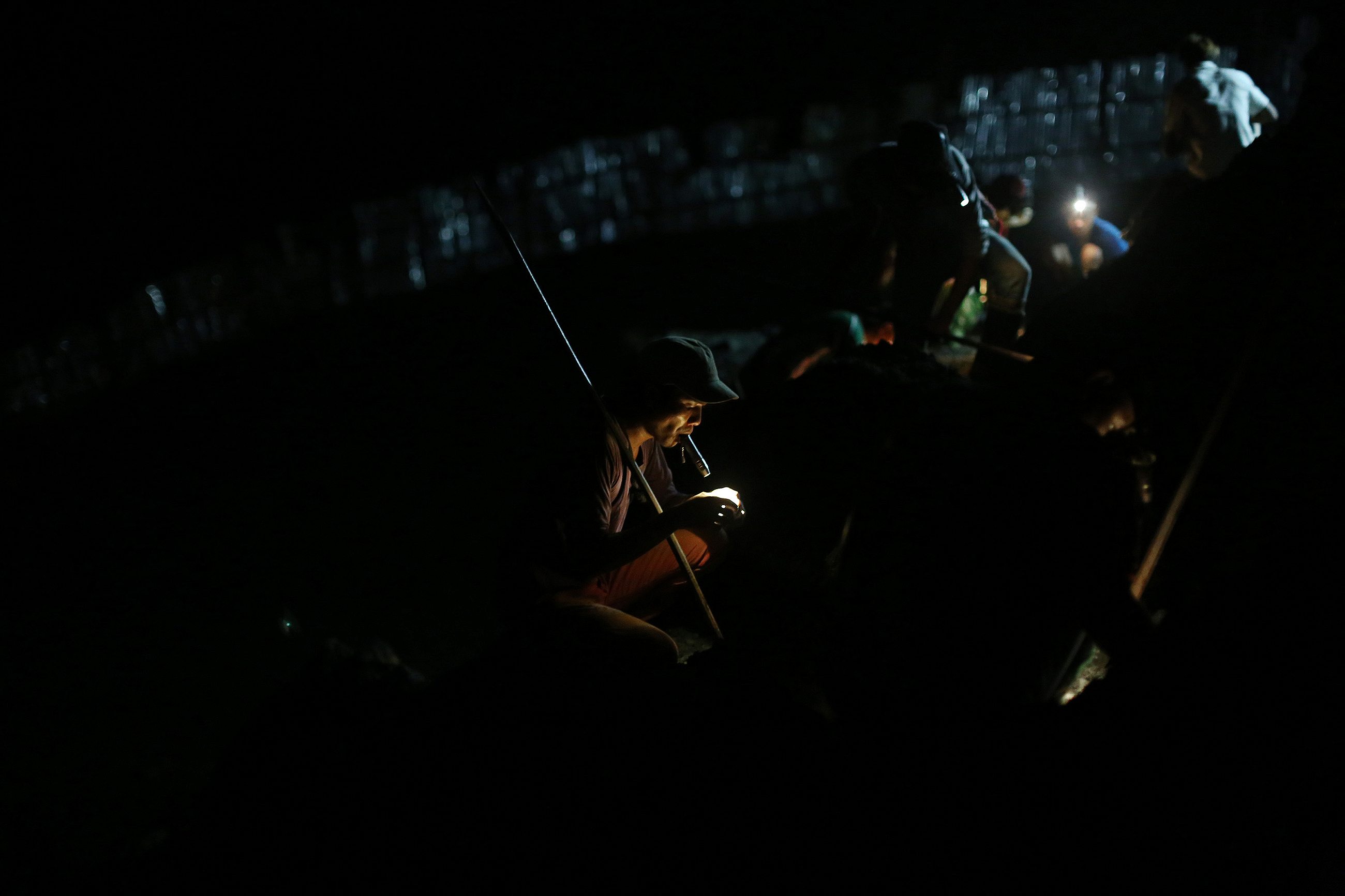

In Hpakant, young men from across the country work in extreme conditions with little to no law enforcement and zero regulations. Many fall victim to hard drugs and poverty. The town is a hotbed for opium cultivation. Intense, unregulated mining has caused several deadly landslides in the past few months. Hundreds have died, yet little to nothing is being done for worker safety.

Despite recent democratic elections in Myanmar, the remnants of the authoritarian military regime still have a stranglehold on the jade industry. A recent report by Global Witness described it as “the biggest natural resource heist in modern history.” Hpakant continues to suffer from crippling underinvestment in healthcare and infrastructure, while the wealth from the rich hills makes its way into the old regime’s pockets.