Stateless in their own country, many of Myanmar’s Rohingya have fled to neighboring Bangladesh. But to get by in a foreign and hostile land, they must often pretend to be locals.

In Myanmar’s 2014 population census, there was no option to register as Rohingya. The only way members of the Muslim minority group could be counted by their own government was if they identified themselves as immigrants from a neighboring country: Bangladesh.

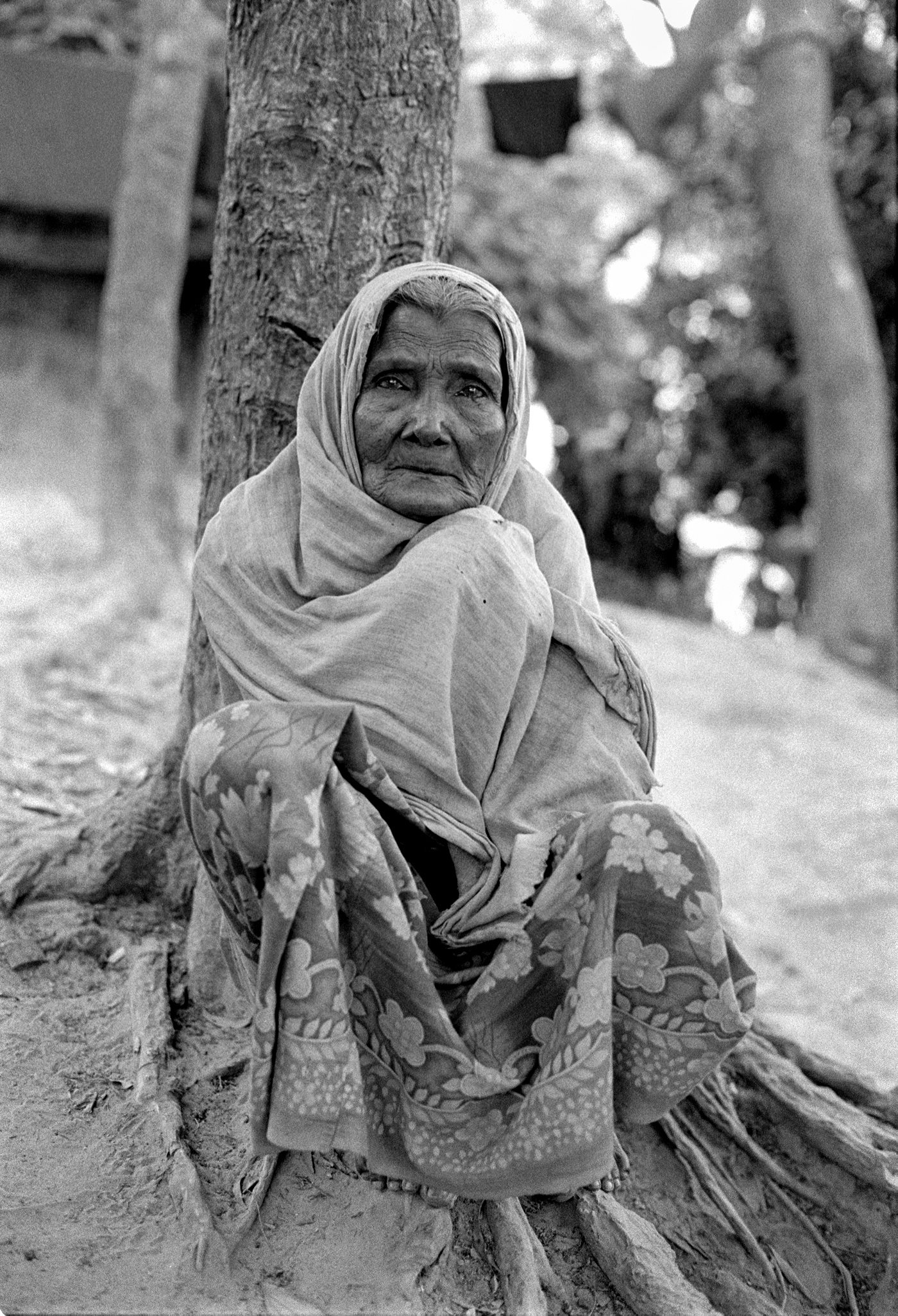

It doesn’t matter how long the Rohingya have lived in Myanmar, officials there see them as invaders who want to establish a Muslim insurgency in the predominantly Buddhist state of Rakhine. In 1982, the government passed a law that failed to recognize the Rohingya as an indigenous race of Myanmar because they were unable to prove residence in the region before the year 1823. But experts agree: the Rohingya have lived in Myanmar for centuries.

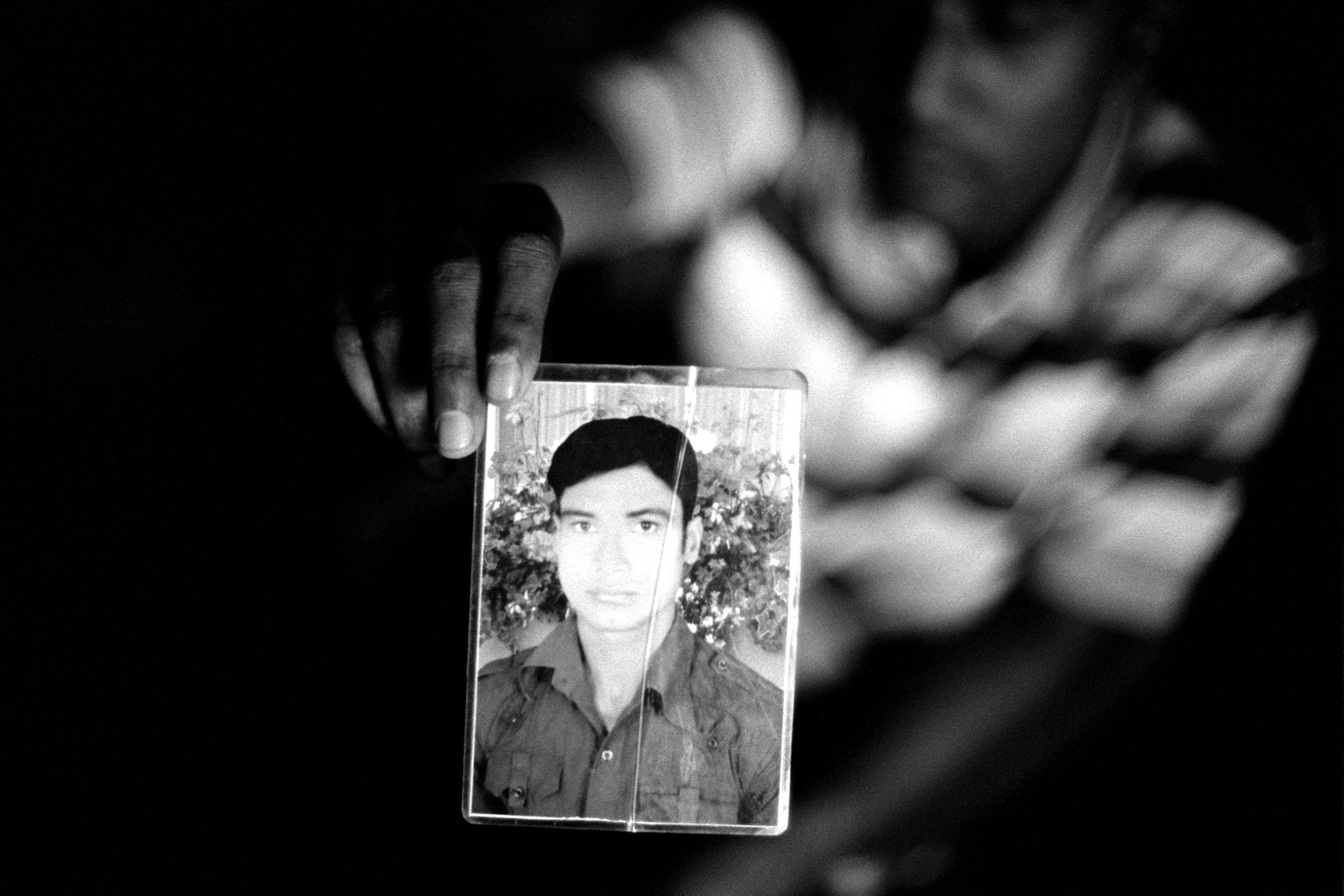

Stateless in their own country, the estimated 1.3 million Rohingya have been victims of restricted movement, land confiscation, forced labor, torture, marriage and child birth restrictions, medical and educational inequalities, false imprisonment, rape, arson and murder. Several armed operations led by Myanmar’s military government were expressly aimed at driving the Rohingya out. In 2012, a series of attacks left more than 140,000 Rohingya internally displaced, forced to live in squalid camps near the Rakhine capitol of Sittwe. Myanmar’s current president, Thein Sein, has gone as far as asking other countries to take the estimated 1.3 million Rohingya out of Myanmar.

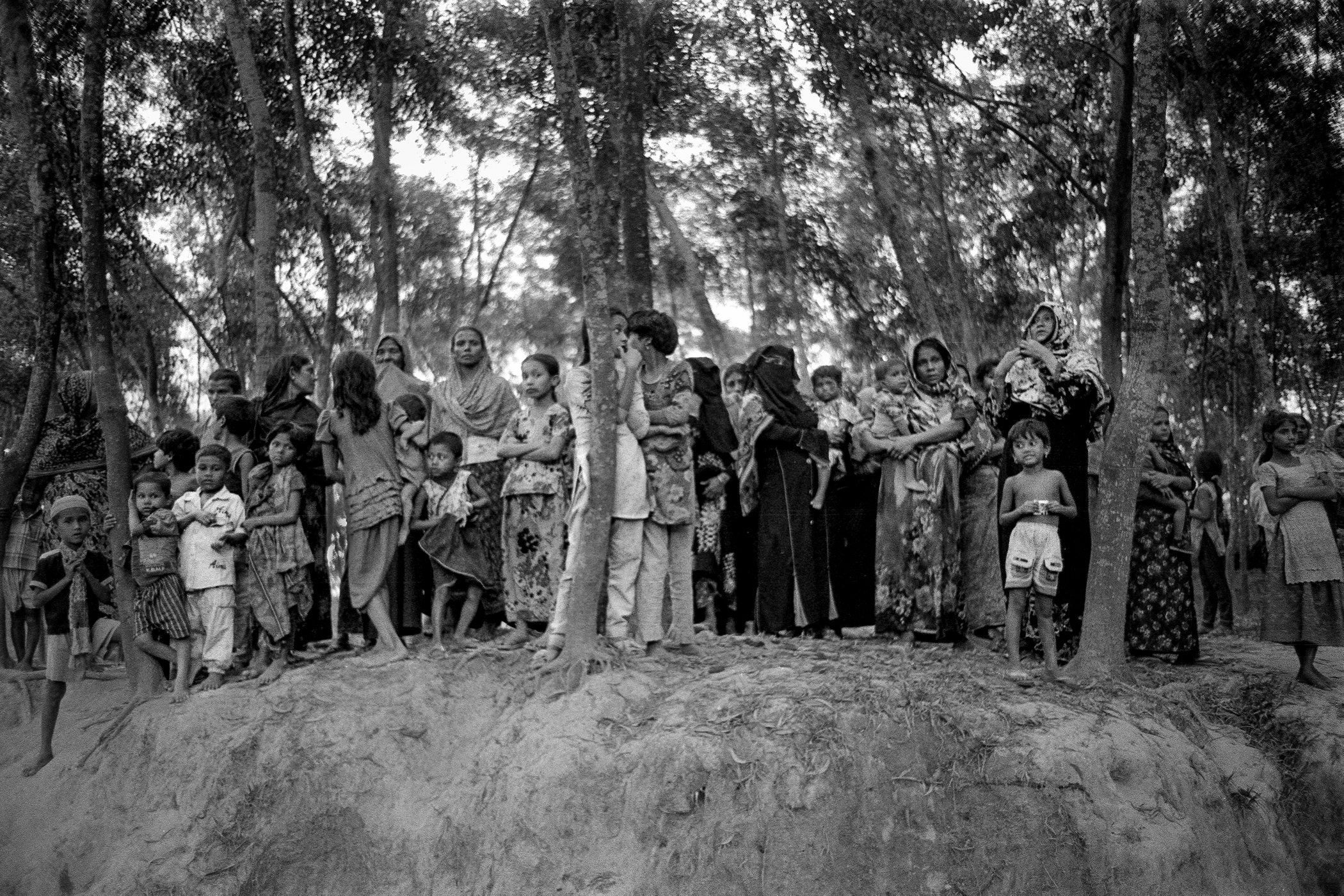

A short trip across the Naf River, Bangladesh has officially accepted 32,000 Rohingya refugees onto its territory while hundreds of thousands of others have come into the country illegally. But apart from their shared religion, Bangladeshis and the Rohingya don’t have much in common. For those refugees that moved into Cox’s Bazaar District or Bandarban District, it’s all about assimilation and keeping a low profile. They blend in and try to become part of a society that is, for them, quite foreign. Those who are particularly good at knowing how to deal with the authorities end up having multiple identities. It’s possible for some to go as far as to enroll in universities and even to buy passports. But in order to do this, they must pretend to be Bangladeshi.

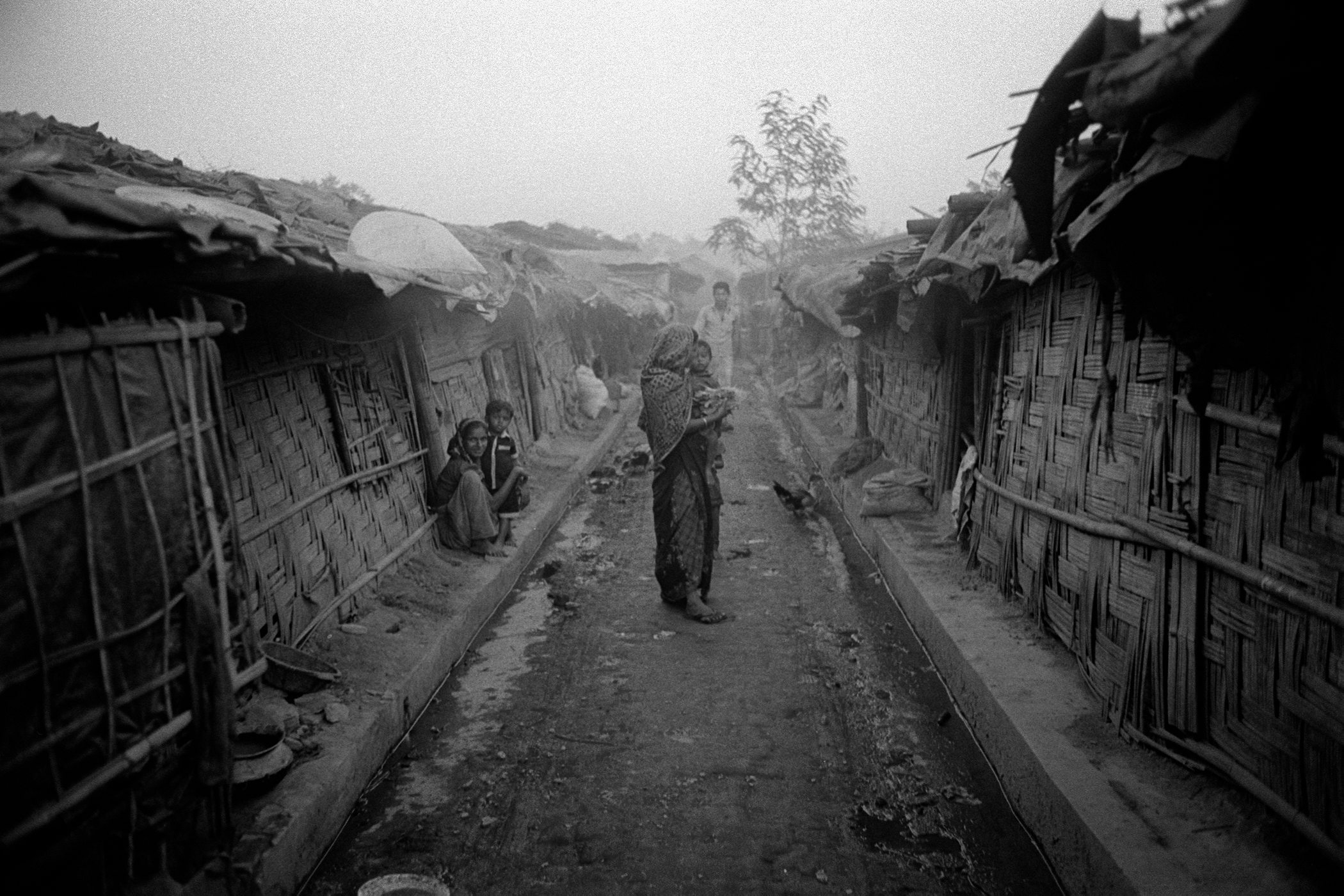

The less fortunate refugees live in camps near the border with Myanmar. Conditions are especially dire in the makeshift camps, which are swelling despite Bangladesh’s decision to close the border in 2012. Families are starving, suffering from curable illnesses and living in huts that become unbearably hot or cold depending on the weather. The sense of desperation is high. Conditions are slightly better in official camps, where about 32,000 people get access to basic medical care, basic education and food rations from the United Nations. Just last month, however, the Bangladeshi government said it was looking to move these refugees, partly because they were hurting tourism in the resort district. Their proposed solution: relocating them to Thengar Char, a remote island that gets entirely flooded at high tide.