In Kolkata, a tranquil and crumbling British cemetery is a haunting monument to an unforgiving time.

During a meandering walkabout one monsoon morning on Kolkata’s famed Park Street, while admiring the contrast of colonial and modern architecture at the heart of this wonderful city, I stumbled upon a hidden treasure. As I slipped through a mossy stone wall enclosure, the relentless hum of Indian traffic stopped and the breeze calmed. It was darker there, the air damp and oddly cool for Kolkata. A cawing crow hopped across my path.

I slowed as I walked through the shadows and memories of ages past. The foliage was thick, filtering out most of the sunlight from this city of souls huddled together. What is this place, you ask? The South Park Street Cemetery, built in 1767 for the earliest British pioneers of the East India Company. This modern-day necropolis is filled with crumbling colonnades, mossy mausoleums, obelisks, sarcophagi, and stone cupolas. It is the final resting place of the soldiers, sailors, civil servants, traders, women, and children who succumbed to the hardships of an unfamiliar and disease-ridden life in the Indian tropics.

India was filled with myriad dangers for its settlers and would be invaders: tropical disease was a great killer in the early days; soldiers died in small battles; and many ancient mariners were lost in shipwrecks. As I walked among the tombs, I felt nostalgia for a time I will never know. A few tightly spaced, crumbling graves lay to the side, and it was hard not to feel a bit of retrospective pity for the inhabitants of those cramped tenements. I imagine they found little solace in India. The vigil of a small community, dependent for news of the outside world on three or four shipments a year and given to deadly boredom in the heat of a tropical summer. If the fates dealt harshly with them in life, they have made no amends to their memory in death.

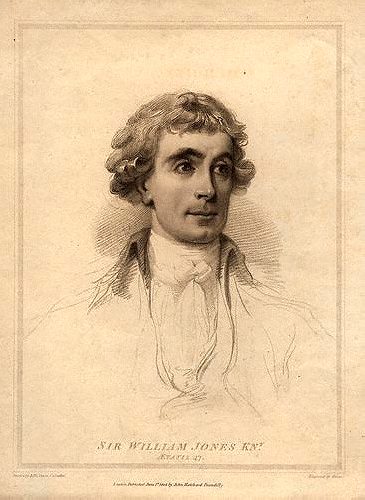

One of the better maintained tombs is that of Sir William Jones, who first came to India in 1783 as a Supreme Court Judge, but soon found that his passions lay elsewhere. Within a few months of his arrival in Calcutta, as the city was then known, he established the Asiatic Society, which still has its headquarters on Park Street. Jones is said to have possessed such linguistic genius that he not only claimed mastery over every major European tongue, but also Sanskrit and various other Oriental languages. At the time of his death in 1794, at what was then considered the ripe old age of 47, Jones had translated important Sanskrit scriptures such as the Bhagwad Gita into English. He believed that for the mind to truly develop, it must absorb the knowledge of other civilizations.

A few decades before William Jones, another Englishman buried here sought to understand the mysteries of Hinduism. Colonel Charles “Hindoo” Stuart started off as a cadet in the Bengal Army in 1777, eventually rising to the rank of colonel despite lacking any significant battle experience. He was considered an eccentric by the mores of the time was said to have “gone native” after he constructed a temple and acquired an Indian wife. In 1778, he wrote an article that urged the military to start wearing Indian attire, and tried to persuade the “memsahibs”—upper class white women—of Calcutta to throw off their heavy corsets and wear the sari. “The Sari,” Stuart wrote, is “the most alluring dress in the world and the women of Hindustan are enchanting in their beauty.”

He was determined to understand the vagaries of Hinduism, a faith that seemed to advocate both asceticism and scandalous physical pleasure; he sought to reconcile why the Christian God endured unbearable suffering, whereas the Hindu deities seemed to rejoice in love. Many colonists found Hinduism disconcerting and strange; not so Hindoo Stuart. He writes in his book The Vindication of the Hindoo that, “Wherever I look around me, in the vast ocean of Hindu mythology, I discover Piety… Morality… and as far as I can rely on my judgment, it appears the most complete and ample system of Moral Allegory the world has ever produced.” His tomb is shaped in the form of a Hindu temple, and the lotus motifs are an interesting touch to what is an overwhelmingly Gothic cemetery.

There is an oft-quoted phrase in Bengal that “What Bengal thinks today, India thinks tomorrow,” characteristic of the cultural and intellectual one-upmanship in which Bengal once engaged. Curiously, the seeds of a Bengal cultural awakening were sown by a young man by the name of Henry Louis Vivian Derozio, who is buried nearby. Though considered an Anglo-Indian due to his mixed Portuguese descent, Derozio considered himself an Indian and was filled with patriotic enthusiasm for his native Bengal.

He is best known as the pioneer of the “Young Bengal” movement, a group of radical Bengali thinkers based in the Hindu College in Calcutta. In 1826, Derozio was appointed as an English professor at at the tender age of 17. His brilliant lectures inspired students; he was renowned for presenting closely reasoned arguments based on extensive reading. He encouraged his students to read Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man and rejected superstition as well as some Hindu customs, including the shunning of widows, which he considered regressive. Derozio took great pride in his interactions with students, writing in his notes, “Expanding like the petals of young flowers, I watch the gentle opening of your minds…”

His close relationships with students, coupled with his free-thinking rhetoric, eventually led to his expulsion from the college. His more orthodox superiors were shocked at what they called the material corruption of student’s moral values and the disruption of peace in society. The loss of employment threw Derozio into poverty, though he still regularly interacted with his former students, encouraging them to publish widely. In 1831, he contracted cholera, a terminal illness at that time. He died shortly after at just 22 years of age. In a final indignity, owing to his proclaimed atheism, Derozio was denied burial in the cemetery proper and was laid to rest on the road just outside.

Those with a more literary mind will recognize the tomb of Rose Alymer, the wife of noted poet Henry Landor. They spent many evenings walking the beaches of their beloved Wales before embarking to the Indian Subcontinent, where the climate took its toll on young Rose. When news of her death reached Landor, he composed the famous “Ode to Rose,” which serves as her epitaph. And buried a short distance away is Lucia Palk, heroine of Rudyard Kipling’s short story “Concerning Lucia.” Not much is known about Palk, but she is said to have been one of the most beautiful women in Calcutta.

As with many old cemeteries around the world, the South Park Street Cemetery also holds its share of haunted graves. A small, pyramid-shaped structure deep in the undergrowth is called the “bleeding tomb.” It is rumored that the tomb oozes a blood-like substance during monsoons. This forgotten memorial belongs to the Dennison family, all of whom died within weeks of one another. The reason is not recorded, and will probably never be known.

One is struck by the ages of the people who lie here, many of them boys and girls barely out of their teens, many of their lives snuffed out in search of land and treasure. There is a great deal to admire in the bravery and stoicism shown by these settlers. The long journey by ship would have been a great hardship, and when they alighted they were greeted by an inhospitable and unknown terrain. This is not an apologia for colonialism, but for all their arrogance and jingoism, I felt humbled by their courage. We like to call ourselves explorers these days, but a booking a flight to another country or a wildlife safari doesn’t compare to the frightening journey into the unknown many of these men and women endured for the sake of trade.

Overhead the clouds darkened and as the drizzle became more insistent, I decided to turn back. I realized that I did not meet a single person while I was there, but then again, one has to make a special effort to find it. As I said goodbye to the elderly caretaker, the loneliness of the place was pervasive, but in a good way. It is strangely comforting feeling to know that— for all the intensity of your emotions—you do not, in the end, matter. The South Park Street Cemetery, on the other hand, will always be here, the big trees full of leaves, the fading light unchanged for two hundred years, and the peace within it lying perpetually in wait.

[Header image by Jari Anttonen]