The historic mansions of the West Bengali megacity are reminders of a richer, more flamboyant past

Bengalis have always believed Kolkata to be one of the best cities in the world. It is, after all, home to Nobel prize winners, mathematicians and scientists, movie directors, writers, and artists. These people make up the essence of what the famous Indian journalist Vir Shangvi called the “city with a soul.”

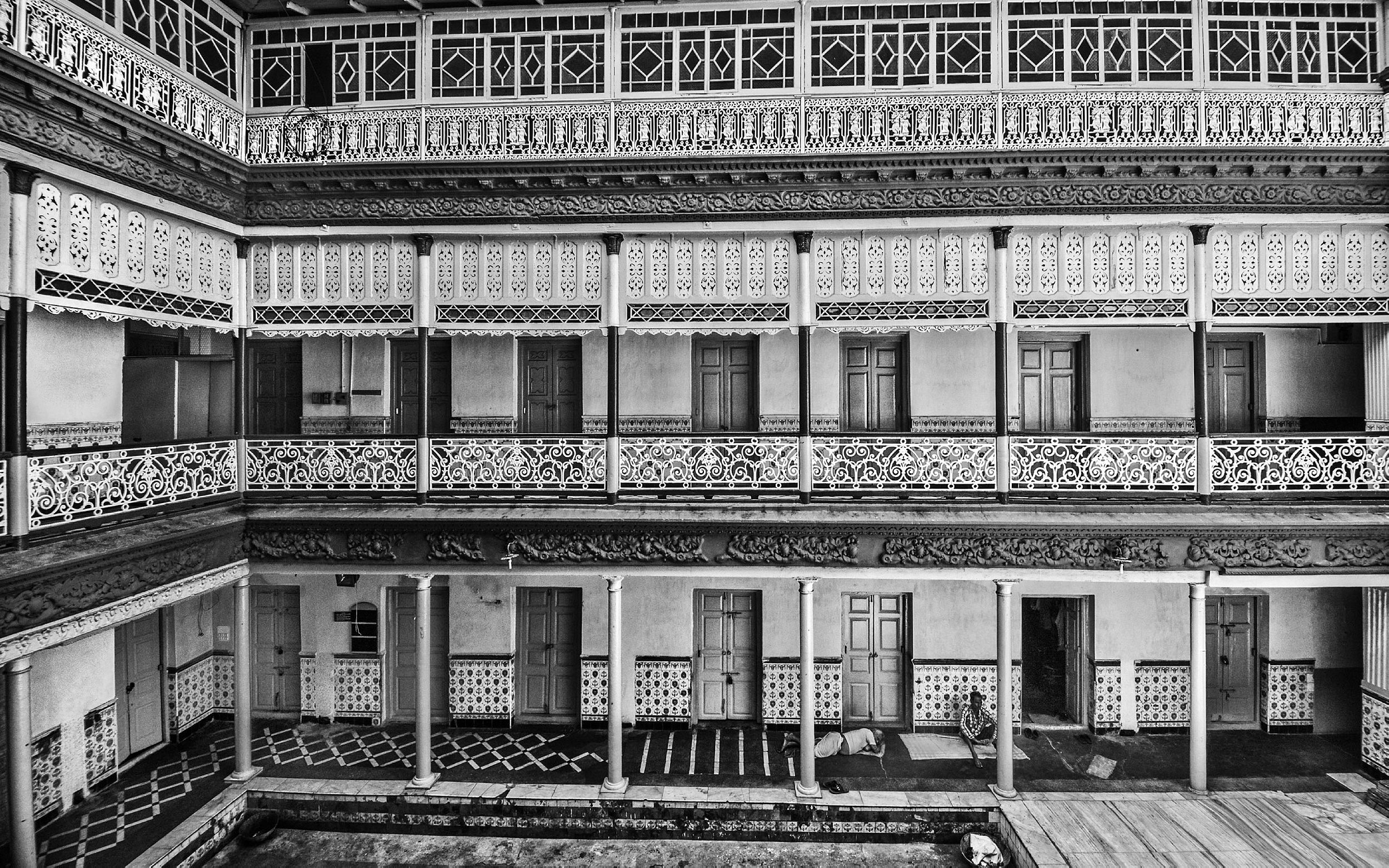

But the buildings also have their own story to tell. When I was about eight or nine years old, my father often took me out for walks in the northern part of the city. I remember looking at the crumbling aristocratic mansions that stood at almost every corner there. I always felt fearful looking at them; they looked like haunted houses. My father would try and explain their history but his lessons didn’t stick, and when I left Kolkata for modern cities like Singapore, Beijing, and Shanghai, I almost forgot this part of my hometown.

In 2009, on a visit back home, my childhood memories of these houses came rushing back. I decided to find them again and started contacting the families who still own them, families who have made enormous contributions to the development of the city. Speaking to them, I felt like I was traveling back in time to the city’s more glorious past, where the Babu culture was at its apex.

Babus were the neo-urban group of high-class, flamboyant Bengali gentlemen who came into being as a result of close interactions with the British in the late 18th and 19th century. They were very rich and they challenged the social norms of colonial Kolkata. Babus showed off their wealth with extravagant festivals and hobbies, like buying zebras to pull carriages through the streets of the city. They also built palaces that followed the architectural design of famous houses in London, like Windsor Castle and Royal Albert Hall.

Ramtanu Dutta, the son of a successful businessman and probably one of the most exuberant Babus of the time, had his house cleaned twice a day with pure rose water that came from the city of Mirzapur. Another Babu, Bhuban Mohan Niyogi of Bagbazar, was said to light his cigars with burning banknotes.

At the beginning of the 19th Century though, the time of the Babus started to fade. Revolutionary movements were flourishing in Kolkata, causing the British to take away its status as a capital city. Trade was severely impacted. The mansions deteriorated as newer generations struggled to keep up with their astronomical costs.

Today, most of these houses are crumbling. The state government has done very little to help, playing the role of a silent spectator. One house owner told me: “Where the whole world is fighting to save their own heritage, we must be the only city in this world not putting any positive efforts to save the city’s culture.”

Over the past five years, I photographed the deteriorating neighborhoods of Shovabazar, Bagbazar, and old Chitpur. As these historic communities disappear to make room for giant shopping malls and skyscrapers, I realized that very soon, there won’t be anything left that would remind us of this history. And with that, I wondered if this deep Bengali pride of Kolkata would soon too become a thing of the past.