As a child growing up in Pakistan, the railway held a special place in Annie Khan’s imagination—even though she never actually rode a train. Last year, she returned to Karachi and boarded the country’s most famous (if slightly beleaguered) line, the Khyber Mail.

Making my way through the traffic-choked streets of old Karachi, I arrive at the railway station minutes before the 10 p.m. Khyber Mail is due to leave. On the platform, red cloth bags filled with letters and packages are being loaded onto the train. Porters are waiting in line to weigh luggage on a massive bright red scale. The caption on the dial face reads ‘W&T Avery Birmingham and Calcutta.’

The machine was likely built by a company based in Calcutta with headquarters in Birmingham, and is one of the many reminders of the sub-continent’s colonial past. The railways once connected Chittagong to the frontier and importing cities during the British Raj, such as Calcutta and Bombay.

The Karachi Cantonment Railway Station is part of the same British heritage, an imposing yellow stone structure set apart from the plain concrete buildings of Saddar neighborhood, a noisy commercial area, one of the original urban centers of Karachi. Stains of Betel leaf (‘paan’) spit and posters on the outer walls of the station were recently removed as part of a restoration project. Inside the station, a pizza franchise has opened and steel benches have been installed in place of splintered wooden ones.

If the railway staff felt any tension from recent events, it didn’t show. A week ago a bomb ripped out a piece of the tracks near the station while a train was boarding, killing an 11-year-old girl. Sadly, death is a common theme at the station. Most often people die while running to catch the trains, a porter tells me. Recently, a young man ran after the departing Khyber Mail. The porters shouted for him to stop, but his foot got caught in the wheels and was killed on the spot.

Although I was born in raised in Karachi, this is the first time I’ve traveled by train in Pakistan. My father used to be an airline pilot for the national carrier, Pakistan International Airlines. We always flew when we traveled. Once, my university arranged a field trip to Lahore by train. My father promptly booked me on a flight instead. In his mind, the trains were unsafe and unreliable. And, as it happened, almost all the other students in my engineering section were boys, which he wasn’t happy about either.

Over the years, the railway assumed a special place in my imagination, even as I heard from friends and relatives about its many shortcomings. This was likely the product of reading old paperbacks about the pre-partition era—flimsy twenty rupee Urdu romance novels that would fall apart after one reading, their purple prose littering my bedroom.

In English literature, trains were even more celebrated. Rudyard Kipling gave them a certain carnival-esque flavor in his book The King and I, with alms seekers and thieves and adventures through exotic lands. The Khyber Mail was called the Frontier Mail in Kipling’s time, and it was a shining jewel of British transportation in the subcontinent. The luxury mail carried servicemen between Bombay and Peshawar. British officers looking out from the cliffs of the northwest envisioned the conquest of Afghanistan and ultimately laying down tracks all the way to London.

Even after partition, the Khyber Mail remained an important train, running from Karachi to Lahore, and on to Peshawar in the northwest. Important members of Pakistan’s military and civilian administration are known to travel in luxury cars, with all the glory of the original aesthetics—complete with plush velvet seats and toilets inside private cabins and personal kitchenettes and cooks. But the quotidian travel experience for the millions of train travelers across the country was largely invisible to me, outside of the British legacy and the romantic landscape of fiction novels.

After graduating university, when I started working in television—with its quick turnarounds and tight deadlines—flying was the only option. The office where I worked in Karachi happened to be just around the corner from the train station, and I would often hear the trains pulling in and out, evoking a nostalgia that was more literary than born from any real experience. When I left the country and moved to New York, one of my few regrets was that I had never taken the Pakistan Railway.

Inside the booking office in Karachi, the ticket agent, an elderly woman, suggests, “Why don’t you take the Awam Express instead? It’s faster and a more convenient ride for families.” A man in line assures me the Khyber Mail has improved in recent years, and now the delays last not more than a few hours each way. I want to laugh, but things could get much worse than that. A well-known travel writer I emailed about the journey warned me about the frequent breakdowns. A family once got stranded in the middle of nowhere and had to survive for days on food bought at exorbitant rates from a far away village before the train was finally fixed. I was traveling with a female photographer colleague, but still the idea of getting stuck somewhere far away was unsettling, to say the least.

The train whistle blows, echoing throughout the station. “Can I carry your luggage?” a porter asks me. I shake my head and push my way into the crowd. The Khyber Mail is parked just ahead—the Pakistan Railways logo painted in fine white lettering in English and Urdu on the side of the engine. Through the windows of the Mail I glimpse families stuffing metal trunks, rolls of bedding, water coolers, and metal containers of food under the berth or wherever they would fit. For the tuck-shops—the small kiosks selling toys, snacks, and everyday items—on the platform, this is a burst of brisk business. Chai vendors scurry back and forth collecting empty glasses from passengers as the train starts to pull out of the platform.

I manage to climb onboard just in time. Taking a left from a set of toilets flanking the rear of the car, I walk into a narrow corridor connecting seven compartments. I enter the second one, indicated on my ticket, and find a group of women seated on the bottom berth chatting. There are enough women riding in business class that the ticket agent is able to group us together in our own compartment. Often when traveling by air in Pakistan, I recall, the ticket agent would similarly seat me next to a female passenger whenever possible.

There are six berths in the cabin: three narrow beds on each side, with a set of small steps in the wall to climb up. The middle bed can fold into the wall so the bottom berth has space to sit up. A young woman in her late 20s dressed in a pale pink traditional Pakistani shalwar kameez, a long shirt worn over loose trousers, gets up and walks to the mirror mounted on the sliding door of the cabin and begins to remove her chador, the large flowing fabric used to cover the body as an outer wearing. I notice her studying me in the mirror. I smile at her and she smiles back. When she sits again, I notice she’s reading a copy of Dan Brown’s Digital Fortress. Later, as we engage in small talk, she tells me she finished her bachelors in pharmaceuticals five years ago, but never practiced. Spending her days waiting to get married, and reading Dan Brown.

The woman seated next to her is only slightly older. A housewife, she is accompanied by her young daughter. They are on their way to visit her in-laws who live in Daharki, a town in the southern province of Sindh. She is reading an Urdu novel about a romance between a Sunni boy and a girl from the Ahmedi community—members of which, according to Pakistani law, are considered non-Muslims. In the end, the girl renounces her faith to be the boy.

Our cabin is full, but the men don’t listen

The housewife and her daughter take the middle bed and I sleep on a bottom berth. During the night the temperature outside drops rapidly. A heavy fog rolls across the window. The motion of the train is heavy and jarring, my spine aches as I lie staring at berth above me, feeling claustrophobic.

After midnight, a group of men knocks on the door looking for places to sleep. The Khyber Mail is parked at Hyderabad Station, just north of Karachi. Our cabin is full, but the men don’t listen. An elderly woman takes charge and pushes the men out, firmly closing the door behind them. “This is the biggest problem we face traveling by train,” the woman traveling to Daharki says. She has traveled on the Khyber for five years, but in recent years, she says, the women-only seating has been eliminated. She tells me that once, in the middle of the night, a man sleeping in the berth opposite hers tried to pull off her blanket. Now she stays awake at night. “Those men were high,” she tells me, her eyes focused on the cabin door.

When it comes time to use the bathroom, the woman in the pink shalwar kameez and I go together—one keeps watch outside while the other goes in. The men loitering in the corridor look at us suspiciously. But our perils are not restricted to leering men. Going from one car to the next means stepping across a three foot wide gap, the rapidly moving ground just below.

Early the next morning, a boy from the kitchen comes to take orders for breakfast. I ask for tea. The women have brought food with them and insist that we share. There are potato cutlets and fried chicken wrapped in tin foil. The mother is curious to know if I am married. I say yes. Then why do I not have any children? I struggle to come up with an answer that will satisfy her, much as I have with my own relatives asking the same questions. Not yet, is all I say.

Although I have eaten with the women, I am still curious to see the dining car. I find it at the other end of the business class section. It’s an open area with about ten tables. An oily dish of biryani is in the works in the small kitchen in the back. There are a dozen men scattered throughout, nursing cups of tea, some of them reading newspapers. I notice a woman sitting by herself off to the side and walk over to her.

She asks me to join her and introduces herself as Ghulam Fatima. She is spreading jam on a toast as she tells me that she’s a health worker. Her family is employed in the railways and she receives free tickets, so she frequently travels by train. She seems at ease in her surroundings. It reminds me of my own sense of familiarity with air travel. She doesn’t seem to mind the men’s stares.

As Fatima takes a bite of her toast, a small cockroach crawls out and lands on my notebook. I shake the bug off immediately, but Fatima does not seem to notice. A moment later, the waiter comes to take my order, but I tell him I’ve eaten already.

At the next stop, in the sleepy city of Bhawalpur in the province of Punjab, much further north, I get off on the platform to stretch. The bright sun warms my body; I’m still cold from the chill air of the previous night. Wandering through the sparsely populated waiting area, I lose track of time and turn around to see the train pulling away. Panicked, I run after it, and manage to climb back on before it gets up to speed. “This is no place to be running, you can get seriously hurt,” the conductor scolds me. But then the man softens his tone. “You are like my own daughter,” he says touching my head.

Having spent a night in business class, I make my way to economy to see how the other half lives. The economy class is the heart of the train. Almost the entire revenue of the railways today is generated from these cars. In 2013 alone, the Pakistan Railways carried forty-two million passengers, the majority of them in economy. The Khyber Mail between Karachi and Lahore runs with two business class cars and seven economy cars. However, this number changes from Lahore onward to Peshawar, where two cars are business, three economy, and the remaining four carry cargo.

Where the business class is a series of closed compartments, the economy class is completely open. There is little privacy here, and nothing to shelter passengers from the elements. The broken windows and open doors allow the wind and the dust in. And as we travel north, the air gets cooler.

The train feels like a refugee camp and a bazaar rolled into one

There are sixty-six seats altogether in the car, but there are far more people—a human being on every available inch of space. Each row is composed of a single seat by the window, with two levels of beds in the center aisle. The bottom bed can also act as a seat for three or four people. Some of the passengers have hung bed sheets, tying one end to post at the top of the beds and the other to the seat below, to provide a semblance of privacy for their families. A woman’s foot in a bright fuchsia plastic sandal sticks out from the sheet near me. I never catch sight of her face. Meanwhile, a man— perhaps her husband or another male relative—sits on an upside down bucket in the aisle, keeping watch.

I take a seat by the window. A group of men sitting in the center-aisle looks at me curiously. They are businessmen, they tell me, and run a store in Karachi selling denim garments and lace. Jeans are a very popular item in the towns and villages across the country. “Nowadays media has advanced so much,” one of the men says, referring to the more common use of western clothing worn by both men and women in television programs and soap operas, “that even if people don’t have enough to eat, they still want to spend on stylish clothing.”

They are on their way to Multan, before continuing onto Lahore. “If we had European standards, it would take us six hours to get from Lahore to Karachi,” the youngest of the three men says. “The Khyber Mail takes 24 hours to cover the same distance.”

At the next stop, more passengers pile on and are forced to sit on the floor. A man selling sweets makes his way through the aisles with a basket on his head. “Khanpur ke pere,” he calls out, hawking a popular sweet treat, considered a specialty of the town of Khanpur. An old man singing hymns and begging for money limps behind him. Between the hawkers, the people on the floor and the bed-sheet tents, the train is starting to feel like a refugee camp and a bazaar rolled into one. When we start to move again, I find a place to stand near the open door. Outside, I spot a man relieving himself in the mustard field with his motorcycle lying next to him—a moment of privacy shattered by the sudden passing of the train.

Walking the aisles, I pass a striking middle-aged woman with high cheekbones. She smiles and introduces herself as Khalida Najmi. She asks the women she is sitting with to move over to make room for me to sit.

Najmi is a politician, she says, and is on her way to Lahore to rally for votes. “Go smoke somewhere else,” she tells a man standing nearby with a cigarette in hand. The man moves away. It is a striking contrast to most of the women I had observed in the economy class, almost all of them cloistered behind makeshift tents or wearing heavy burqas. She wears a chador over her head, as I do, but she also wears bright lipstick and carries herself with an air of confidence.

Najmi is from Ichhra Shadman, a small town near Lahore, and has long been involved with the affairs of her community, especially in settling disputes for the women of her town. Seeing her popularity among her peers, her husband encouraged her to run in the local elections. Najmi won and soon became an even more central player in the community. However, her husband changed his mind and asked her to quit. Najmi says she refused. She’s been divorced for three years now and is raising her daughter by herself.

Najmi tells me to come visit her when we arrive in Lahore. I ask her for her address. “When you come to my hometown, just ask anyone for me, they all know me,” she says.

Night falls and the lights of Lahore appear on the horizon. For many years I traveled there almost weekly for work. What little sightseeing I’d done had left me with an impression of an old but vibrant city—its streets lined with historical buildings and alive with rich cultural heritage. Whereas Karachi was unapologetically commercial in character, and a city of concrete and steel, Lahore exuded an air of mystery from its crumbling stones.

Lahore is above all, a city of shrines. As it happened, many of the disembarking passengers were there to attend an annual urs of Data Gunj Buksh, a revered Sufi Saint whose death anniversary attracts thousands of devotees every year to the city’s largest shrine. I decide to follow the pilgrims to the shrine the next morning.

The lanes around the shrine are closed off to vehicles. A whole bazaar has been set up just for the urs. Hot food is being prepared in large metal cauldrons. Small shops sell green shrouds, dried almonds, and sugary treats. A dhol wallah, a man beating a barrel drum, plays a mesmerizing beat. A man walking past suddenly joins in the dancing, his eyes closed and a smile on his face. He then touches the dhol drum in a sign of respect and walks away.

The great green dome of the shrine looms overhead as I enter with a group of pilgrims. It had been segregated a few years earlier. Other than some men selling rose petals inside bright pink plastic bags, the women pilgrims are separated from the men by a glass wall. While we wait to enter the grave of the saint, a woman in a burqa sitting next to me asks what I am writing in my notebook. I tell her I’m a writer.

“Are you a writer as well?” I ask her.

“I am a married woman,” she replies. “What have I got to do with writing?”

Another woman joins our conversation. She has come to pray for an ID card, she says. Confused, I ask her what she means. Her husband, who passed away two years ago, had been a railways electrician. She had gone to the railways to collect his pension, but when she was asked for her identification she had nothing to show. She’d never had an ID before. When she went to get one made, the men at the government office told her that there was someone with her name and fingerprints already in the system. They asked her for three thousand rupees to resolve the issue, but she did not have the money. After trying for years, she says, she has come to the shrine in the hope that the saint will get her pension from the railways.

I meet another woman named Mehmoona. She’s been attending the urs for years and comes often to help keep the shrine clean. Mehmoona says she does it to gain the good graces of the saint. “It’s incredible,” she explains. “Ganj Buksh was the student of Makki Ali Shah [a much older Saint, also revered for his teachings]. Shah’s shrine is nearby but it is Gunj Baksh who draws hordes every year.”

I ask her why there were no female saints.

“That is God’s way,” she replies. “He knows best.”

A nearby food stall displays goat testicles and kidneys

As midday arrives, I decide to head back to the station and wait for the next Khyber Mail continuing onward to Peshawar. It seems that life around the station has formed its own economy to serve the coming and going passengers. Tacked to the low fence of the railway park is a sign advertising ear-cleaning services. Strange, somewhat painful looking implements, are arranged in a neat order on a wooden crate under the sign. A scalp massage costs 100 rupees. Shabbir, the masseur, has carefully spread a bed-sheet out on the grass, upon which one can receive a vigorous massage while taking in the chaotic Lahore city traffic around the park. He has two customers at the moment, a police constable and a hawaldaar, a junior constable, from Kashmir who are touring Lahore. The massage is the highlight of their day, they tell me.

A nearby food stall displays goat testicles and kidneys on a plastic sheet. Small billboards advertise lodging for the night inside impossibly small looking buildings. Mattresses and quilts can be rented for the night. Families sleep inside what look like vacant shops. In one corner, a man lies unconscious next to a woman seemingly oblivious to the syringe sticking out of her arm. Addicts and vagabonds mingle with the tired passengers.

The heat is oppressive, so I finally make my way back inside the station where creaky fans whirr ineffectually. But the shade is welcome. The railway cafeteria on the main platform is empty and the lights are off when I peek in. In the bleak afternoon light, a server is waving flies off the samosas. There is a waiting room for the passengers, but it has been leased to a private contracting company and turned into a VIP waiting lounge. A little further along, eight families sit on the platform, or on the few available seats. They are all waiting for the Samjhota Express that is scheduled to arrive the next morning. The train will take them across the border to India.

Many of the passengers have come from far away villages and cannot afford a hotel. An elderly woman tells me she fell asleep at the little hotel behind the railway and missed the last train. Now she is determined not to leave the platform until the train arrives.

These India-bound passengers will have to go through several baggage checks, extensive paperwork, and questioning before they cross the border. A journey that would normally take several hours will take them three days.

“The trains here in Pakistan are not even 50 percent as good as the trains in India,” says one passenger. On the other side of the border, the Khyber Mail becomes the Golden Temple Train, running from Amritsar to Bombay, he tells me with a smile. It is quite a name, I think to myself, wondering how the train’s conditions measure up to the lofty title.

After the Samjhota Express pulls away, I’m standing on the platform killing time when I spot a woman in a burqa standing with several railway officers. She has an official looking badge around her neck; it seems she’s an employee of the railways. And indeed, moments later, she and two of the officers climb aboard a special train car designed to check the tracks for flaws. I quickly follow them onboard and ask one of the railway employees who she is. She is a senior official he tells me, and motions and introduces us. She introduces herself as Ambreen Zaman, and after a quick exchange of hellos, I follow her onboard the train, for a quick cup of tea.

We step inside a small room in a private cabin with plush velvet seats. She sits across from me and removes her face covering after making sure the door is closed. Zaman is a railway engineer, and is on an annual inspection of the tracks. The train we are sitting inside of is commissioned especially for the purpose, carrying along with Zaman a whole group of railway engineers and inspectors. She has been working in Pakistan Railways for the past 13 years. Previously, she was pursuing a masters degree in business administration when she saw an ad in the papers for railways engineers, and her father encouraged her to apply.

“My father was a great man,” she says proudly. “He was an Air Force officer. My mother was a bit worried when she had second daughter. But my father said, ‘They are my fairies.’ When he was on his deathbed I said to him please scold me once, even if for no reason, just so I would know what it’s like to be scolded by a father. But he never ever raised his voice at me.”

A railway employee knocks on the door. She quickly puts her face covering back on and opens the door. The train is ready to leave. I thank her and quickly jump off.

The scheduled arrival of the Khyber Mail has been delayed by several hours due to an accident on the track. Nobody knows the exact details but it is some time just after sunset when it finally pulls into the station.

The economy class is packed. I place my jacket on the floor of the corridor and sit there. A man in a red sweater and patent leather shoes with big gold Louis Vuitton logos offers me a place on the top berth in the compartment where his family is sleeping. “It’s only women and children inside,” he says reassuringly.

I climb onto the top berth and cover myself with my jacket and go to sleep. In my dream, I see a man enter the cabin in the dark and slowly pull the jacket off me. I wake suddenly, bumping my head on the ceiling of the train. I look around, but there is no one there, other than women and children sleeping in their berths. I hardly sleep the rest of the night.

At Attock Station, I get off on the platform. It’s around 4 a.m. and in the cold early dawn haze, men in heavy shawls and pakuls, a northwester style of woolen hat, board the train. The chalk white walls of the railway station look ghostly in the grey light.

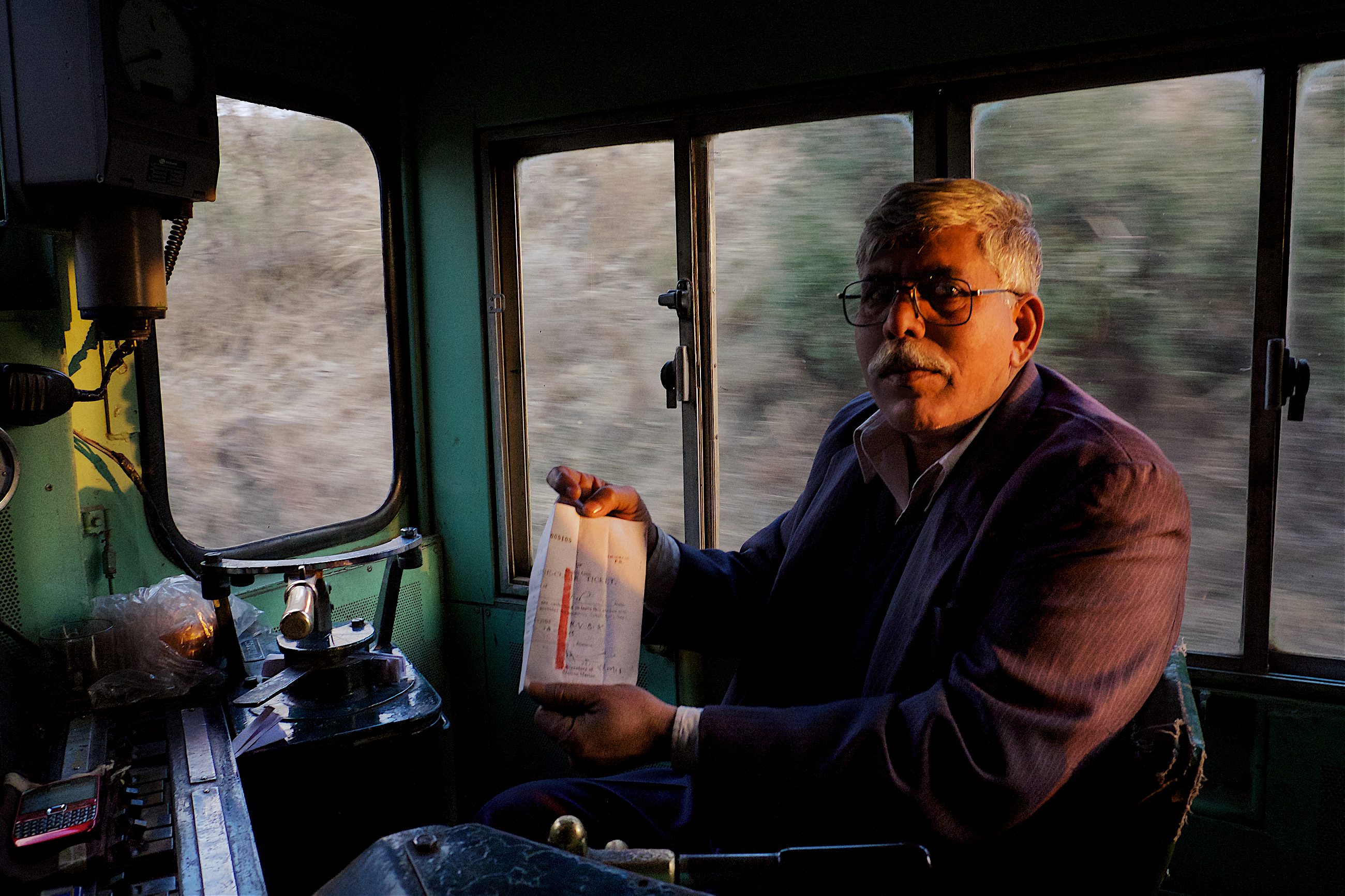

I make my way to the engine, where the driver, Ghulam Murtaza, sits waiting for the passengers to board while his assistant prepares tea in a tin cup on a heating coil. I ask Murtaza if I can ride in the engine. He hesitates; his superiors will not allow it, he says. I tell him that I’ll crouch down while the train is on the platform so no one will see me. That makes him smile. Something in my remark reminds him of his daughter, he tells me.

They make a space for me behind the driver, and after ten minutes or so we pull out of the station. Almost immediately, the train climbs onto a massive bridge. I can see the Indus River flowing hundreds of feet below, and for a moment I am reminded of flying in the cockpit with my father as a child.

The train has officially entered Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, the Northwest Territory bordering Afghanistan. As the sun rises, revealing massive gorges and craggy mountains, the Mail begins to pass through a series of low tunnels. Murtaza covers both ears with his hands as we enter the darkness.

The man standing next to me is Zaddan Khan, a 57-year-old electrician who has been working in the rails since 1977. He has a weathered face. His hair dyed with henna (an herbal hair color commonly used by both and women in Pakistan). It’s soon clear that he enjoys telling stories. Khan starts telling me about Sheila, the dancing girl who performed every night for the builders of the Khojak Tunnel in the province of Balochistan. The tired workers would lavish most of the day’s earnings on the girl.

I ask Khan if there are any female train drivers in Pakistan. The crew starts to laugh. “The railways did train two women once,” says Murtaza. “But halfway on their first run the train stopped. The emergency crew arrived to find they had both fainted!”

Zaddan Khan laughs with him. “This is not a woman’s job,” he says.

After four hours, the Khyber Mail reaches the outskirts of Peshawar and slows to a crawl. In the distance an old man in a green jacket with a shock of white hair and sharp green eyes waves to the train. To my surprise, Murtaza stops the train for him. The man, who speaks in a raspy voice, says he wants to be dropped off in the city. Murtaza nods and the man climbs aboard.

I ask Zaddan Khan about the train delay earlier. I’d heard from another passenger that there had been an accident on the tracks. “That was a suicide,” he explains. “Every month there are three to four suicides. Sometimes it’s a child or a man. But mostly it is women. Eighteen days ago, near Peshawar, a woman covered her face in a dupatta and laid her head on the tracks.” He pauses. “All it takes is one moment to end it.”

After dropping off the passengers at Peshawar Station, the train arrives at its final stop, a servicing area where the crew can rest. There, parked on the track across from the Khyber Mail, is a vintage steam engine, its gleaming surfaces in stark contrast to our dust-caked engine, like an apparition from another time, straight out of the pages of the books I’d read growing up.

‘Khyber Steam Safari, no. 2216’ is written across its front, and the Pakistani flag has been painted above the name in bright colors. The engine had been a tourist attraction running between Peshawar and Landi Kotal four hours away, one of the crew tells me. “But the Khyber steam engine stopped running five years ago,” says Mubarrid Hussain, a sub-engineer, “because of the Taliban. The government will not allow it because of the security threat. But we hope to bring the steam engine back again soon.”

My journey has been a long one, more than four days altogether. After disembarking in Peshawar, my final stop, I can still feel my body shaking as if I were still on the train. The bustling city seems quiet in comparison with the deep drone of the engine. After spending a night in the city, I decide to fly back to Karachi. I make it home in four hours.