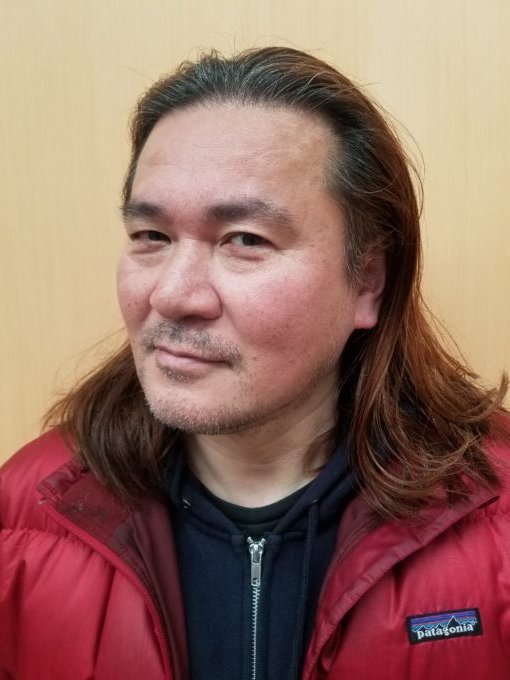

Tokyo Fixing with Shinji Nohara

Legendary Tokyo food journalist and fixer Shinji Nohara talks to Nathan Thornburgh about Anthony Bourdain’s first show, the scourge of the gastronaut, and what makes Tokyo such a deeply good eating city after locating the perfect 7 a.m. breakfast at Haneda Airport: stellar ramen and cold beer.

Shinji Nohara has been making good things happen for visitors to Tokyo for almost two decades—ever since a lanky camera-shy writer named Anthony Bourdain arrived with Lydia Tenaglia and Chris Collins to shoot their first television episode ever. Shinji was the fixer for that episode. First, he found out what Tony’s food-kinks were, and then he delivered those deepest desires in one single sizzling experience that, by Tony’s own admission, changed his life. That’s Shinji’s job, and nobody does it better than him. So of course, on a layover from Bangkok earlier this month, I asked Shinji to jury-rig two hours of wish fulfillment for me. In this case, it was a layup for the man: a bowl of Setagaya ramen, an extremely cold and fresh beer, and a deep conversation with Shinji in Haneda airport’s new terminal is, to be totally honest, my dream breakfast.

Here is an edited and condensed version of Nathan and Shinji’s conversation. You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Nathan Thornburgh: Shinji Nohara and I are live from Haneda Airport!

Shinji Nohara: The international terminal!

Thornburgh: International terminal. We’re in an airport and you got me a coffee, which is sort of cheating because we just had a beer. But we were eating ramen.

Nohara: We need the caffeine.

Thornburgh: We need the caffeine so I can get through this layover. Since it is a layover and I don’t have a ton of time, let’s get to it. I think all your social media handles say Tokyo Fixer. Where’d that name come from?

Nohara: I got the name because I do the things that a fixer is supposed to do. And I know it has a shady image, but I like that. Someone said to me, “You should call yourself Tokyo fixer,” and I like that.

Thornburgh: That is true. I mean, there is the Quentin Tarantino-style fixer like Mr. Wolf, who’s going to come in and help you chop a body up. Journalists have a more established, slightly less adventurous version of a fixer which is just somebody who has local contacts. You’re kind of in between the two. How did you become a fixer?

Nohara: I first started out working with TV crews, magazines, and journalists in the early 2000s. I had been writing about restaurants in Tokyo, and Tony [Bourdain] asked for my advice on where to go. That’s how I ended up being a fixer.

Thornburgh: And a beautiful marriage was born. It is pretty crazy that your first TV experience would be with him.

Nohara: He had written Kitchen Confidential, and he was working on his first show, A Cook’s Tour. People saw the show and said, “Hey Shinji, can you take us around like you did for him?” That was my side job, actually. My magazine business going down at the time.

Thornburgh: Like any good magazine business around the world. It’s all a giant trash fire.

Nohara: And I never thought my side business would get busier than my main business but that’s what happened.

Thornburgh: And now you’re the go-to guy for very elite-level food-fixing. There’s only one of you and there are thousands of restaurants in Tokyo. You can find somebody else if you’re here and you’re just like, “I’d like to get some sushi in Tokyo.” But if you want to dive deep, Shinji’s the guy who you call. So when somebody does call you up, what’s your process for helping them out?

Nohara: First of all, I have questions.

Thornburgh: You need to get to know this person a little bit (laughs). Because this is a city where any desire can be fulfilled. You just got to figure out what the hell that desire is, right?

Nohara: I mean, in most of the cases people say, “I leave everything in your hands.” Okay. I try to play it by ear. The process of getting people in restaurants is changing because you have to book in advance for many places. For some famous places, you have to book maybe two or three months. You have to book up to a year in advance for some restaurants, a year. I don’t believe it…

Thornburgh: They’re fake full?

Nohara: Yeah, fake full. They say they’re full until 2020. What?!

Thornburgh: Right. So you want the serendipity that you used to have so can run and just say, “We’ll figure this out.”

Nohara: Yes. What’s your mood? Are you in the mood for ramen? Are you in the mood for fish or beef? There are millions of questions and options that need to be sorted out.

Like any good magazine business around the world. It’s all a giant trash fire.

Thornburgh: Speaking about having to book out more in advance: every time I visit Japan, there’s a lot more people visiting here. Has that put pressure on the restaurants or on the food scene here?

Nohara: Lots of restaurants, they start using online booking systems. It’s good for them, but for me it’s… I’m not criticizing it. For example, ramen is not the kind of thing that will make me say, “I want to book ramen.” I’m not going to say, “I want to eat yakitori (grilled, skewered chicken) two weeks from now on this day.”

Thornburgh: No. Yakitori is about you sitting at a bar—you’ve been drinking—and you’re thinking, “You know what would be really fucking great right now? An amazing yakitori.” And you go and hit it. Booking it in advance—that would be like scheduling sex, right?

Nohara: It’s not fun.

Thornburgh: It’s not what we’re looking for. How do you stay on top of all the different restaurants and all the changes? Do you keep a little book? How do you find all the little places around the country?

Nohara: Through word-of-mouth.

Thornburgh: That’s the way to get the stuff. Do you worry about giving a certain restaurant too much publicity?

Nohara: If the place is in Tokyo, I want to keep it secret. But if it’s in Sapporo, I don’t worry about it too much.

Thornburgh: Because it takes extra effort for people to get on the plane or the train to get up there?

Nohara: And it’s such a small place to find.

Thornburgh: One of the things that I’ve heard about you is that you have that thing that some other people have, which is the ability to just look at a storefront—maybe it’s something about the smell, maybe it’s something about the way the cook looks when he’s taking a smoke break out front—and you have a gut instinct about whether that place will be good or not. It’s a gut thing. It’s an instinct. It’s a real gift. Sometimes I don’t have that eye.

Nohara: You have to make hundreds and thousands of mistakes.

Thornburgh: Good, I’m on my way.

Nohara: Yeah, just keep working on it.

Thornburgh: For the first-time visitor to Tokyo, what are a couple of little things that they should keep in mind when they’re trying to eat in this town?

Nohara: Definitely open your mind. Try to go on side streets, back alleys. Usually, the good restaurants are in the basement or the second floor of a building.

Thornburgh: The ones that are on the first floor, the prime retail spots, they don’t have to work as hard.

Nohara: If they have a huge, flashy sign, that’s not good.

Thornburgh: One of the beauties about eating in Japan is that you can take risks because—even at the shops that aren’t the greatest—there’s still a baseline level of care about what people are doing. You can fly a little bit. You’re not going to fall too hard.

If people want to get in touch with you, how do they do it? Should they DM you on Instagram?

Nohara: Instagram is one way to get in touch with me, but I can’t check all the requests.

Thornburgh: You’ve got to know somebody that knows Shinji to get ahold of him at this point.

Nohara: That’s the better way to find me.

Thornburgh: Right, so they’re pre-vetted. That’s also a way for you to make sure that the person who’s seeking you out is not going to waste your time.

Nohara: I can give, again, some tips, but I have just one body.

Thornburgh: No matter how much ramen you eat, it’s just one body. It makes it all the more pleasurable that I was able to get you here to share your wisdom for people who don’t know a guy who knows you. Thank you so much for coming to the airport this morning.

Nohara: Thank you for having me on your show. I’d be pleased to do it again.

Thornburgh: Maybe less early in the morning? Maybe with more notice?

Nohara: Yeah, more notice and maybe we can hang out for 24 hours.

Thornburgh: For sure. You showed up to talk to me during my three-hour layover before I go back to New York. Three hours in Tokyo is a hell of a lot better than no hours in Tokyo.

You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Episode 29 Show Notes:

Up Next

Illustrator Edel Rodriguez is Stress‑Testing Democracy

Yasmin Khan Cooks Her Way through Palestine

Writer Yasmin Khan, author of the new cookbook Zaitoun, whips up an Old Monk hot toddy and talks about the joys of Palestinian cooking.

What Jason Rezaian Learned as a Prisoner in Iran

Journalist Jason Rezaian, the author of the new book Prisoner, talks about his 544 days of imprisonment in Iran, what he thinks of his captors, and his stubborn hopes for Iranian society.

A Life in the Commune with Tanja Fox

The oldest squatter’s commune in the world, Christiania, is under threat from both the narcotics trade and mass tourism. Tanja Fox isn’t afraid.

Jennifer Ching is Dismantling the System

How do you tackle poverty in a city like New York City? Jennifer Ching of the North Star Fund has some ideas.