Illustrator Edel Rodriguez is Stress‑Testing Democracy

Edel Rodriguez talks with Nathan Thornburgh about how his childhood in Cuba makes him uniquely equipped to illustrate our troubling political climate.

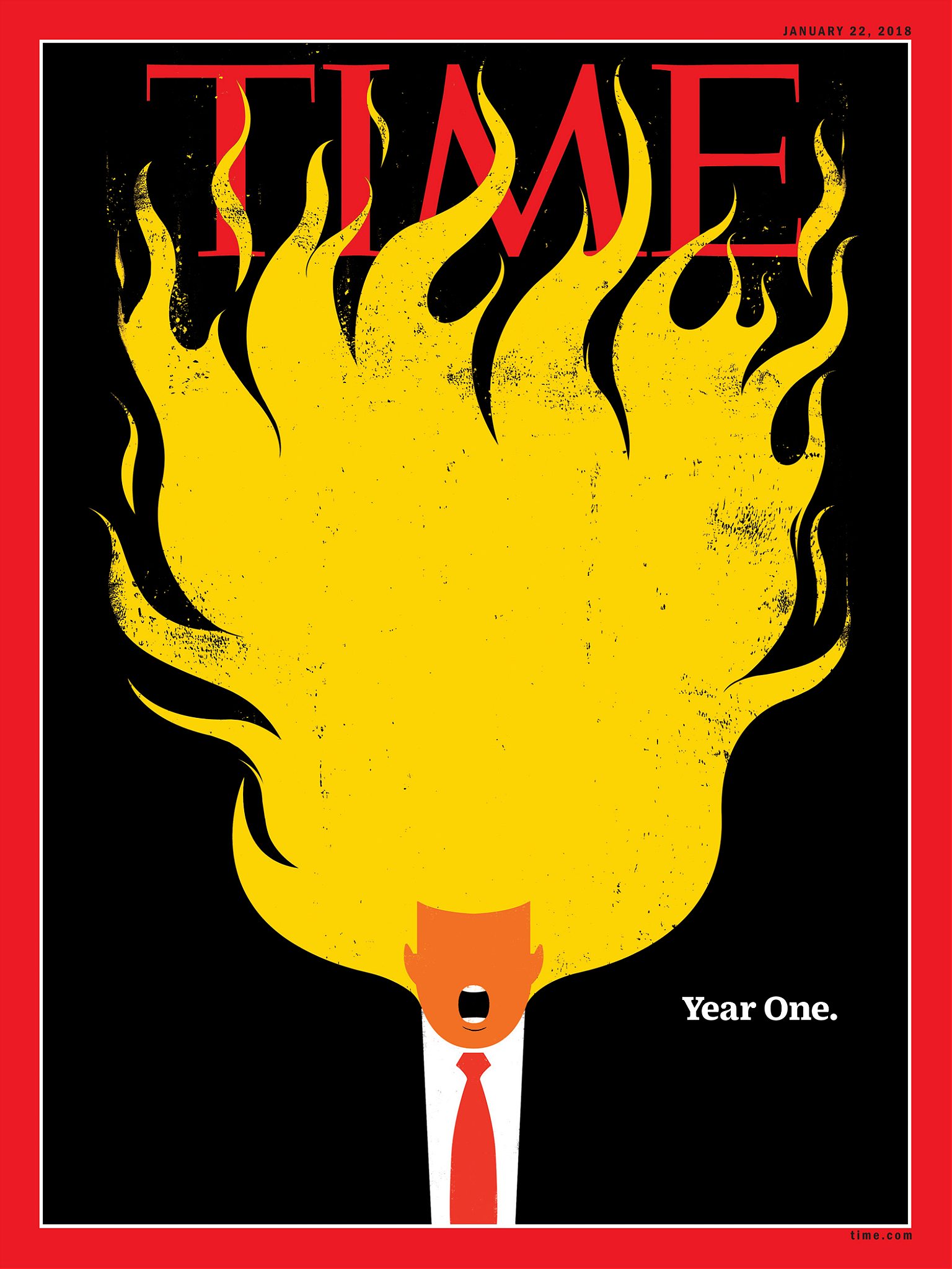

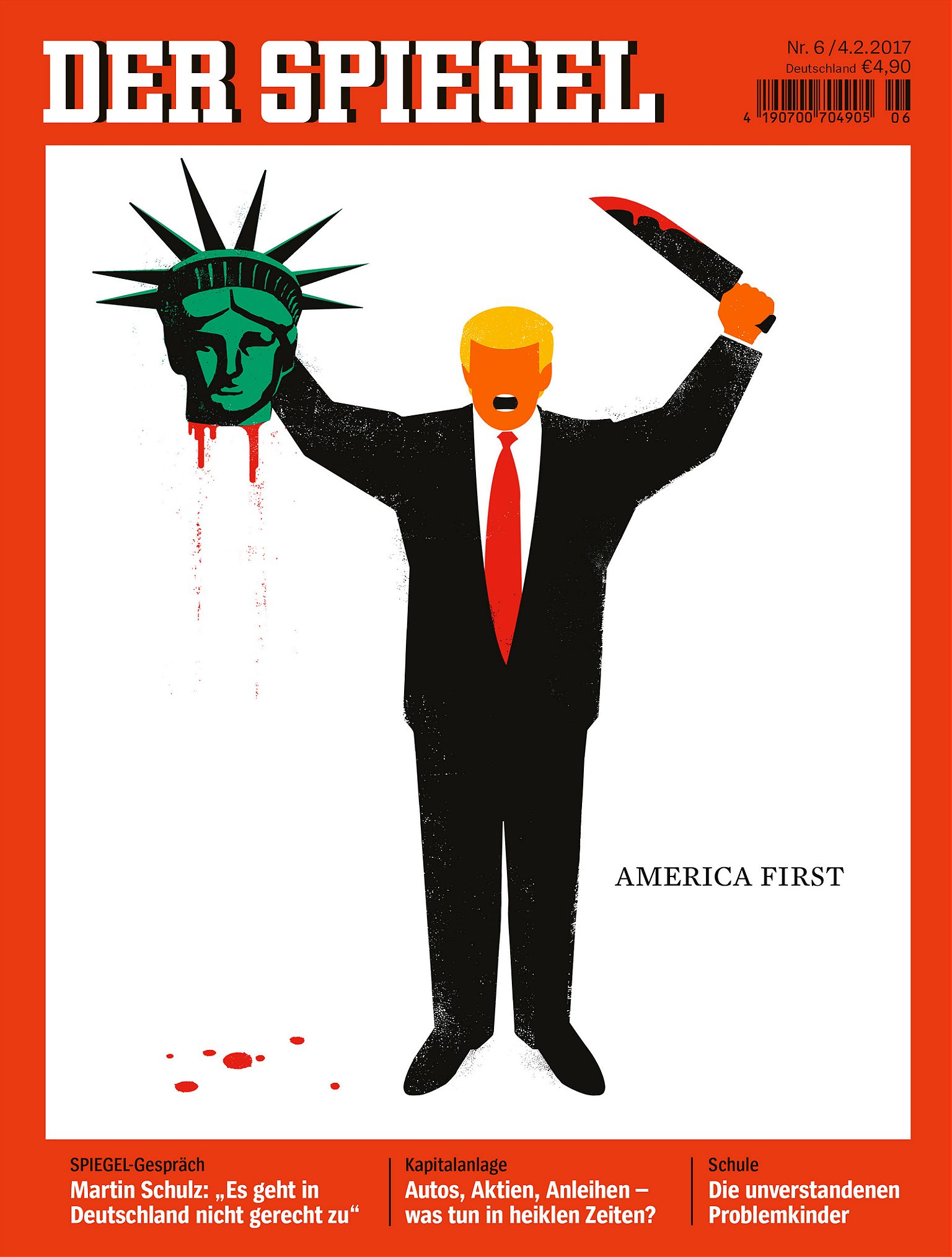

You’ve seen his illustrations on the cover of TIME magazine or Der Spiegel, or on signs wherever the Trump-phobic meet and rally. His depictions of the 45th president—as an ISIS executioner, a Klansman, or just a melting orange mess—do exactly what he intended. They provoke, they inform, they communicate the loud perils of our moment, wordlessly. When host Nathan Thornburgh started The Trip podcast with Anthony Bourdain a year ago, he knew exactly who he wanted to get to design our logo: Edel Rodriguez. Edel joined Nathan in The Trip’s Brooklyn studio to drink a bunch of “bullshit coconut waters”, and to talk about how his childhood in Cuba prepared him for becoming as Fast Company has called him, the Illustrator-in-Chief.

Here is an edited and condensed version of Nathan and Edel’s conversation. You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Nathan Thornburgh: So, we’re recording this episode from the Roads & Kingdoms studio in Brooklyn. During each conversation, my guest and I share a drink that usually involves liquor. I’m not drinking alcohol because of this dry January (I have to say it feels like a dry millennium). Edel isn’t drinking either so we met up in the shi-shi bodega downstairs to find a non-alcoholic beverage that has… meaning. We’re going to be talking about your life and work and Cuba, which is a place that has a lot of coconuts, so it seemed like coconut water was the way to go. We’re going to do a taste test of several brands of coconut water.

Edel Rodriguez: There used to be just one type of coconut water, and now there’s colored coconut water. It’s crazy.

Thornburgh: I can remember a time, growing up in South Florida, when coconut water wasn’t even bottled. I’ve got a lot of doubts about this entire endeavor, but we’re going to check it out because we have our first bonafide Caribbean guest. Edel Rodriguez was born in Cuba and is here to taste Brooklyn’s finest bullshit coconut waters on The Trip.

Edel, you and I know each other because we worked together at Time Magazine for a few years. You were an art director there. There’s kind of a wall between the writers and reporters, like me, and the art crew which would make our stories look good. I knew you as really pleasant and smart to work with, but I didn’t really know the full Edel. So, let’s go through that backstory. Let’s go through how the Mariel boatlift is part of your story.

Rodriguez: The Mariel boatlift took place in 1980 in Cuba. It was 20 years after the revolution. The seventies started off well in Cuba, but towards the end, a lot of tension started building because people didn’t like the government. People didn’t like the way the revolution was turning out. So in April 1980, a group of people took over a bus and a crashed it into the Peruvian embassy in Havana and sought asylum in the embassy. As soon as the gates were crashed, tens of thousands of people went into the Peruvian embassy to try and get asylum.

In one of his fits of anger, Castro said that anyone who wanted to leave Cuba should get out. He told people in the United States to come to Cuba and get their family members. Before that, you would get shot if you showed up in Cuba to get your family. All of a sudden people started going down to Key West, Florida. My family had already been quietly trying to leave Cuba via Spain.

Thornburgh: You had a plan in motion?

Rodriguez: We had a plan that my dad had been working on for a while.

Thornburgh: How old were you during this time?

Rodriguez: I was eight at the time. My dad didn’t want his kids growing up in this country because he saw what was happening to my sister. My sister was six years older than me, and she was getting a government education and being sent to work camps. Children would be taken their families for [long periods] of time. You were working in the fields from about six or seven in the morning until one in the afternoon, and then you would go to school after that. So, it was this sort of indoctrination of children for the party.

Thornburgh: Your dad was a photographer, right?

Rodriguez: My dad was a little bit of everything. He was the town photographer. Before that, he was a chauffeur. He also managed some government restaurants. He was doing a lot of things.

Thornburgh: The hustle in Cuba is unbelievable.

Rodriguez: Yeah, but people with the CDR (Committee for the Defense of the Revolution) were watching and received some threats. So by the time the announcement about the Mariel boatlift was made, my dad was already thinking that he had to get out of there as soon as possible, otherwise he was going to go to jail.

So around April 20th, my aunt was going to come to visit us. When my dad went to pick her up at the airport, my aunt said she had a boat on the way to take my family—we lived in El Gabriel—to the U.S.

Related Reads

Thornburgh: What do you remember from that time? I mean, you were eight going on nine.

Rodriguez: I remember my mom told me that we were going to go on a trip to see family in America and that I needed to give away my things. I remember just looking around to see what was important to me. I had a couple of fish and I gave them to my best friend and asked him to take care of them.

Thornburgh: I grew up in Key West so I was on the other side of the Mariel boatlift. I was five, I think when it happened. I have no memories of it, but it’s funny because the legend of the boatlift has kind of grown on the Key West side. If the number of people who claim to have been captains or like part of a crew in the Mariel boatlift were actually true, it would have been an armada of like 500,000 boats.

Rodriguez: It went on for about six months and in the end, there were about 125,000 people that made the trip. The boat my family was on was like 68-foot shrimper sailed by two Jamaican guys. We boarded the boat around six or seven at night and stayed on it for a few hours. We eventually took off as a flotilla of about 15 boats. We arrived in Key West around seven in the morning the next day.

We stayed at a processing center there for about a day. I’ve been thinking about that experience lately. The difference between the experience that I had compared to what the Honduran and Guatemalan kids are getting now at the border. We were kept together as a family the whole time. We were welcomed. We’re given so much food. We were given little packages with a toothbrush, toothpaste… When we landed, I thought this place is so clean and there’s so much stuff here. There were toys and we were allowed to pick as many as we wanted them.

So, there was this sense, this idea, that America is a wonderful, great place that welcomes people. Now I’m seeing kids are being split up from their families and put in cages and all this shit.

Thornburgh: And imagine walking for six weeks. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the language of invasion—the minor trickle that is coming over the southern border is almost a historic low levels of people who are crossing the Mexico border, especially compared with 125,000 Cubans. The Mariel boatlift was a big deal and it changed a lot of communities, and nobody was like, we shouldn’t do this.

Rodriguez: Cuba has always been this special place because of the communism issue, I think that’s what it was.

Thornburgh: So after arriving here, you eventually winded up going to the Pratt Institute. You started to have this great career, but you didn’t go back to Cuba for a while.

Rodriguez: Yeah. That first time I went back— you know I never had issues with depression, but when I came back to the U.S. I wanted to be left alone for a week. I just wanted to cry in my bed and sleep.

Thornburgh: Why? What had you seen?

Rodriguez: The country that I had left was just a disaster. Back in ‘94, ‘96, People were cooking over diesel fires in the backyard. There was no water and no electricity. It felt a bit like a war zone. When you see your family and your grandparents living in the middle of all that and you know it would be easy to fix, it really upset you. There’s a lot of good things going on there now. A lot of young people that I know that are in the arts and music.

Thornburgh: I had gone down there and spent some time down there in 1999. I didn’t go back until 2009, and it was kind of crazy to see the changes. The buildings were the same, but just better maintained and with nightclubs. Those weren’t really around in ’99.

Rodriguez: What’s strange about it is that it’s not publicized. There’s no way to know what’s happening in an official way. But you can meet young people who’ll tell you there’s this thing happening over there and there. I’m very aware of that. I’m cautious of what I do or say sometimes when I’m there. Here in America, I can say and do whatever I want. In Cuba, something I say or do could affect my aunt and my cousins. That’s part of the control that they have.

But, you know, one of the first things that sent me off with this whole Donald Trump thing happened about two years ago when I was at a school event. I said something about Trump and then the person I was with told me they didn’t want me to talk to a specific teacher because they didn’t know what that person thinks of Trump. And I’m like, hold on a second. Alarm bells went off in my head because here’s someone telling me to keep it low in this country, in the United States. I’ve heard this before.

Thornburgh: That’s an old memory for you.

Rodriguez: Over the last two years, I’ve heard things that would act like a little trigger in my head. I don’t like what’s happening. I don’t like how people are talking, the way that Trump is doing things like insulting people. Like when Fidel called people worms or scum.

Thornburgh: So people reading this are probably are familiar with your powerful illustrations of Trump for magazine covers. I think Fast Company called you the Illustrator-in-Chief.

You kind of draw an extreme version of your reaction to something that happened, but then Trump kind of works his way into that version of your reaction. So like when he started making racist remarks, you drew him with a big old Ku Klux Klan hood on and then Charlottesville happened. All of a sudden that image is a magazine cover for TIME or Der Spiegel.

Rodriguez: I’m about one year ahead of the curve.

Thornburgh: I think my favorite illustration—favorite is a weird word to use—but the one that just struck me the most is this image of Trump with a beheaded Statue of Liberty. It’s a really raw image. I feel that the power that your illustrations have could only have come from you because of your background. The connection seems very clear to me.

Rodriguez: From the very beginning, I took this situation very seriously. My images are sometimes funny but they’re a little creepy at the same time. When I was making the images, I was thinking about what could possibly happen in terms of the current climate in America and I wanted to present that to the people and get them to pay attention. Sometimes people ask me why I do these illustrations. I do it because of my background and history. I can tie the stories together. I know what a dictatorship looks like, and I can see how this can slowly become one. I’m able to see that in ways that other people can’t, and I can communicate what I’m seeing. I’d rather be painting something else. Trust me.

This is what America is really about: the idea that you can just say whatever you want. Let’s see where this story ends up.

Thornburgh: You’ve talked about wanting to make images for people who don’t necessarily speak English. You’re going right for the human core where everyone can understand your message.

Rodriguez: Sometimes I sacrifice a lot of artistic detail because we, as artists, tend to make things for other artists. I take a lot of that stuff out because I want to communicate with someone like my dad or a construction worker. I spent a lot of my youth in junkyards and mechanic shops with my dad. My dad was a truck driver in Miami, and I get a lot of joy when one of my images can be understood by like my dad, or a farmer, or someone who isn’t keeping up with all the subtleties of a situation or whatever, and then some Ph.D. candidate will get the same feeling from the image. Also, a lot of my work gets seen worldwide. So you have to make images that are not language-based, you know?

Thornburgh: And the threat is global, so people better have an understanding of what’s going on.

Rodriguez: People from other countries look at me and say, “You’re insane. What are you doing?” Because they know what the repercussions would be in their country for doing what I’m doing. I can do whatever I want. This is what America is really about: the idea that you can just say whatever you want. Let’s see where this story ends up. Either America’s a great country and you can make images criticizing the president in the strongest way possible, or it’s not and I go to jail. I’m willing to take the risk.

Thornburgh: Putting democracy to the test. Man, I appreciate that you’re out there. I have such respect for the work that you do. Edel Rodriguez the Great. Thanks for talking to me.

Rodriguez: Thank you.

You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Up Next

R&K Insider: Save our Stinky Tofu

How Vietnam Eats Today:

Q&A with Daniel Nguyen

Ahead of our League of Travelers trip to northern Vietnam, R&K’s Charly Wilder caught up with Daniel Nguyen, an activist, distiller, researcher, and our host for this fall’s journey into the highlands and beyond.

Making Waste Less Wasteful

In rural British Columbia, Catalyst Agri-Innovations Society is harnessing the power of poop.

A Cold Room for a Warming World

A Nigerian start-up takes on the problem of food spoilage at all steps of the production chain, one solar-powered cold room at a time.

25 Things to Know Before You Go to Yerevan

From wine to brandy to dressing for the opera, a smart guide to Armenia’s ancient capital.