A Life in the Commune with Tanja Fox

The oldest squatter’s commune in the world, Christiania, is under threat from both the narcotics trade and mass tourism. Tanja Fox isn’t afraid.

Not all revolutionaries wear bandoliers full of bullets. Some of them tend beautiful little gardens next to a cottage they built out themselves in a neighborhood called Dandelion. That’s the kind of revolutionary that Tanja Fox is. Tanja is an old friend of The Trip host Nathan Thornburgh, and she has spent her entire life living a little bit differently, in one of the world’s most fascinating districts: the commune of Christiania in Copenhagen, Denmark.

As a social experiment, Christiania has been remarkably resilient. The bit of squatted military base turned hippie utopia has lasted more or less independently almost 47 years now. As you’ll hear in this episode, it is under threat like never before from the twin menaces of a hardcore narcotics trade and, increasingly, mass tourism. Tanja and Nathan sat in Tanja’s house last spring, while birds plucked from a Disney film serenaded them, and talked about how to live your politics in one of the world’s great social experiments.

Here is an edited and condensed version of their conversation. You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Nathan Thornburgh: I’m very happy. It’s mid-May in Copenhagen and everything’s blooming and the Japanese Paradise Apple outside is like this pink cloud that’s floating behind these picture windows. It’s pretty ridiculously idyllic. There’s just a lot of birds who are out there singing and as soon as we started recording, they just kicked the volume up a little bit. It’s their showtime.

Tanja Fox: It is. I told them yesterday, at a community meeting, that we were doing the podcast today. I told them that they’d get extra bird seeds for a little more singing tomorrow morning.

Thornburgh: As with any good intentional community, the birds are also consulted. So, Christiania is an old military fort. This little part of it here is called Dandelion.

Fox: Yes.

Thornburgh: In Danish that’s…

Fox: Mælkebøtte.

Thornburgh: I’ll-

Fox: You can’t say it?

Thornburgh: I can’t … Dandelion is a little community within a community. How many people live in Dandelion?

Fox: About 80. It’s mostly families who live in this area. A lot of people here who have lived here since Christiania was created. We know each other. It’s like a family.

Thornburgh: Tell me about your relationship with Christiania

Fox: In the late sixties, the government had a military base in Copenhagen. They realized that having an active military base next to Parliament, and next to the Queen was really stupid when you are not best friends with Russia. They got rid of the personnel and then they didn’t have a plan. They just thought they could leave the empty military base there. I don’t know what they were thinking.

Thornburgh: They originally built this to keep the Swedes out?

Fox: They built it to keep the Swedes out about 150 years ago. Anyway, during [the late 60s] there were no jobs and no apartments for young people. It was really hard to get an apartment in Copenhagen.

If you wanted a rental, you would have to be married and expecting [a child]. Then you could maybe get an apartment. In that period, there was the awakening of the youth in America. Women’s rights. Peace and love. Vietnam.

Thornburgh: Summer of ’68.

Fox: At that time here, there were a lot of workers in the area around the military base, it was a lot of workers. They were mostly men who would build ships. They would live in small apartments surrounding this military base with five kids and no toilets or showers. They would use a community shower or public bath.

Thornburgh: Like tenement living.

Fox: Yes. These people were actually the first people to get into the base because they could see from their apartments this green area with lots of empty buildings. They snuck in and made a little campfire, and had a barbecue, and drank some beer. They just enjoyed themselves and let the kids play.

Related Reads

Thornburgh: That’s like the origin story for all the great movements, you know?

Fox: Isn’t it? Then some young hippie person came by. From there, things progressed really, really fast.

Thornburgh: The hippie person comes by…

Fox: Yeah, and then somebody writes a little story in a left-wing newspaper and the headline is Take Bus Number Eight to Freedom.

Thornburgh: Take Bus Number Eight to Freedom?

Fox: That was the number of the bus at the time for this area. My mom came here about 10 days after. She was a political activist. She was part of a quite famous political theater group. They had a meeting place in another part of town, but they came here and thought this is a great place.

Thornburgh: She was of an era in which people wanted to live their politics, too.

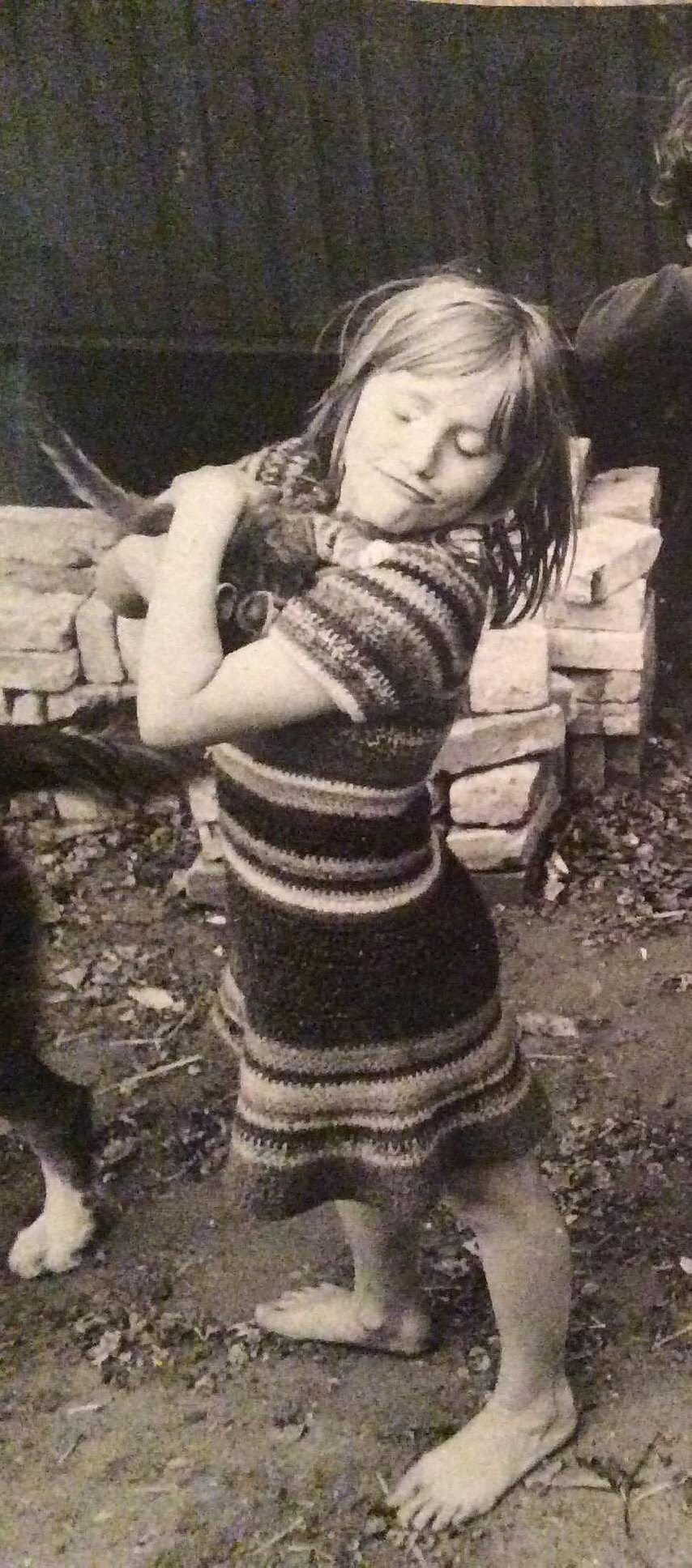

Fox: Yes and they did that here. I think they were really tired of the very strict way they were brought up. They had a really hard time with authorities. So, being a child of that, authority was not anything in my life. I don’t remember my mama saying no. It was a thing that didn’t exist because she just didn’t believe using authority to raise children.

Thornburgh: Yeah. She would have been raised during the war?

Fox: Yes.

Thornburgh: Northern Europeans don’t fuck around when it comes to their children and the general orderliness of life. It’s very interesting to see this group of people who had an allergic reaction to that.

Fox: They totally did. And I think their vision is absolutely beautiful. I get teary-eyed thinking and talking about it, but I do think it was a bit over the top. I think children need direction.

Thornburgh: Are you talking about small things like having a bedtime and should you brush your teeth?

Fox: Yes, and food.

Thornburgh: And food?

Fox: Yes, stuff like that. Sometimes it could be like, “Hey, mom I’m hungry.” But yeah the food is over there. And the people who were supposed to cook the food were maybe too stoned or they were doing something else. I have memories of me not having food. My mom has other memories. She doesn’t like it when me saying this. I’m sorry Mom. I love you.

Thornburgh: One of the things that makes you pretty remarkable is that you were here in Christiania from the very beginning. You were four when you moved in. What are some of your earliest memories of Christiania?

Fox: Well, it was like a ghost town. Also, I think a lot of people from our generation have this memory of freedom. When you left the house, you left the house. Mom and dad couldn’t control you because they couldn’t get in contact with you. It was like a playground. There were lots of strange things here because it was an old military place. There were leftovers from those military days, and it was exciting to find stuff here.

Thornburgh: You could be scavenging for all kinds of things.

Fox: We were definitely squatters. The government didn’t want us here. I understood that much from listening to the grown-ups talk.

Thornburgh: Did you worry about it as a child?

Fox: I worried a lot about it. I would worry that there wouldn’t be a house when I got back home if I went to somebody else’s place. The government took Christiania to court and we lost. We didn’t have the right to be here, but then it was called a social experiment and then it was okay for us to be here. They didn’t send in the police when they won the case so they accepted us.

Thornburgh: That moment, that would have been in the seventies at some point?

Fox: That was in the seventies.

Thornburgh: They had a court order and they could’ve just come in and cleaned everybody out?

Fox: They could’ve come in, but then they had nowhere to put us. There were a couple of hundred young people speaking their minds.

Thornburgh: Yeah, troublemakers.

Fox: Doing political theater and taking off their bras in public. If they had to put those people out in the streets with the kids… that’s not a great picture.

Thornburgh: That’s very funny. So when you first come into Christiania, most people come in off of Pusher Street. And it’s the main entrance. This is the place that you call downtown and it’s a very different vice compared to here. We have the birds chirping here, and down there, it’s filled with a ton of people because there are visitors and people coming for the businesses. [The drug trade] is both an attraction and an ailment in the community. I think probably when people have heard about Christiania—and this is probably true for a lot of Danes—they think about Pusher Street, not about the things that you’ve been talking about, the extraordinary exceptionalism of this place after almost 50 years of independent living. Those are ideas are lost to the image of Pusher Street because that’s where you buy hash.

Fox: And a lot of people, including Danes, come in, walk to the end of Pusher Street, and then turn around. They go out because they think they’ve seen Christiania.

Thornburgh: That’s the stuff they came for.

I am against Capitalism in its raw form.

Fox: Pusher Street has nothing to do with the idea of Christiania. Yeah, maybe the hippies wanted [cannabis] legalized and stuff, and I don’t mind if it’s legalized. I think it’s stupid that it’s not legal. People who are sick need to smoke a joint or something. But what makes me an odd person is that I am against Capitalism in its raw form. In that way, I don’t mind people making a living but that way of doing it is really against my point of view. And I think people don’t need that much wealth. If you have food and stuff, why do you need more all the time?

Thornburgh: I don’t know that a lot of people are having a really good time in Pusher Street. It seems like pretty intense, pretty competitive.

Fox: I don’t like walking through there.

Thornburgh: The context for this is interesting. Weed is very illegal in Denmark. Pusher Street is not some kind of state-sanctioned free-fire zone. It’s actually just an illegal drug market that has taken advantage of the insular nature of Christiania. The police have these incredible raids and they’ll just tear everything down. Then the next day people build it back up.

Fox: Not even the next day, a few hours later. As soon as the police are out they will start rebuilding and selling again.

Thornburgh: Right, so it’s just like a little society. You’ve got your crime. You’ve got your high aspirations. You’ve got your decent people. You’ve got your confused people.

Fox: It’s sad that we use so much time dealing with Pusher Street. I think it could be fun using more time building funny playgrounds, or people’s housing, or Kindergartens.

Thornburgh: Every once in a while when drug dealers are worried about a raid or something they’ll stash some shit somewhere in someone’s yard. It feels like they are trying to drag the rest of the community down. And it makes you guys have to take a stand for your own property.

Fox: It’s frustrating. People can do what they want, drink wine, or smoke whatever. But I’m really tired of Pusher Street.

Thornburgh: I’m with you. Let’s leave Pusher Street behind and go back to the 1980s, 1990s. Did you ever leave Christiania?

Fox: Yes, I did. For short periods of time, but I always came back. It’s like it drags me back in. I don’t know what it is.

Thornburgh: One of the things that is different from the last time I visited five or six years ago, is that there are actually a lot more tourists in this part of Christiania. It’s much thicker. You have a lot more people who are coming up here and it’s a pain in the ass.

Fox: Totally.

Thornburgh: Tell me about tourism here and what that’s like living here? And why it’s actually more pronounced even than before.

Fox: We are being integrated, we are being normalized, we are becoming a part of Copenhagen.

Thornburgh: You essentially made a deal with the government to raise enough money to buy this land and normalize all the structures of ownership and renting so that you wouldn’t have that eternal squatters fee in perpetuity.

Fox: And it also means that for example this building has been preserved. There are a few houses that we already tore down: We took down seven houses and we built five in other locations. There are houses further out in the green area that have to go. That’s part of the deal with the government. Some people have made those houses by themselves from scratch and it’s a lot of emotion to take somebody out of their house in that way. But that’s the deal we made.

Thornburgh: So, you made this deal and that also means now that the city of Copenhagen can turn around and sell Christiania as a distinct experience for visitors. Have they been successful in doing that?

Fox: Yes, they have.

Thornburgh: The mass tourism in Copenhagen is intense and Christiania is now a part of that. We’re now living in a time in which everybody has a camera in their pocket and wants to take 100 pictures a day to prove that they were somewhere. I’ve heard you kind of talk about how Christiania is not a petting zoo.

Fox: Yes, yes. I don’t know if you noticed, but downstairs, it wasn’t like that when you were here the first time. Now I have plastic on the windows that you can’t see through because I was just sick of having people looking through the windows and also taking pictures through the windows into my house.

I also have this funny sign, “Beware of the grumpy old lady,” hanging outside. But I don’t wanna be the grumpy old lady. It’s not the people themselves. It’s the number of people, and all of them asking the same question. Even though I believe that there are no stupid questions, when you’ve heard the same questions 100 times a day, you get tired.

Thornburgh: Right. Has anybody thought about limiting the number of visitors in any possible way?

Fox: But you can’t do that because it’s a public area.

Thornburgh: Yeah, right. Travelers, just keep in mind that when you go visit someplace, you are a guest. It’s that simple.

Fox: Very simple.

Thornburgh: Thank you for being so open when you could have been very tired of people like me. I feel very fortunate to be in your life. I appreciate it.

Fox: Well, thank you for coming.

You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Up Next

Beyond War with Yuri Kozyrev

Instant coffee in Galway with Matt Orlando

Nathan Thornburgh and star chef Matt Orlando of Amass Restaurant drink lousy instant coffee in Galway and talk about running a true zero-waste kitchen in the age of greenwashing.

A Decade of Images in One Iraqi City:

Q&A with Photographer Cengiz Yar

Documentary photographer Cengiz Yar discusses his nine-year project documenting Mosul and the so-called war on terror’s long-term effect on the northern Iraqi city

Tackling Southeast Asia’s Protein Crisis

In Southeast Asia, the Protein Challenge is aiming for nothing less than a total transformation of regional food systems. The solution? Empowering and uniting the protein system’s various and diverse actors to create change from within.

Electioneering on the Eve of the Virus

Nathan Thornburgh and photographer Shane Carpenter were in New Hampshire last month for their longterm reporting project on the state’s odd presidential primary. In hindsight, it looks more surreal than ever.