What Jason Rezaian Learned as a Prisoner in Iran

Journalist Jason Rezaian, the author of the new book Prisoner, talks about his 544 days of imprisonment in Iran, what he thinks of his captors, and his stubborn hopes for Iranian society.

It’s the kind of story no journalist wants to tell: the one of his own arrest and that of his wife, the story of 544 days in captivity, too much of it in solitary confinement, far from his hometown in Northern California. I thought I knew the story of Jason and Yegi Rezaian—after all, my Roads & Kingdoms partner Anthony Bourdain had talked often about their captivity while they were in prison, and brought all of us together after their release. But you have to read Jason’s book about his ordeal. It is harrowing, intimate, and full of things I had no idea about.

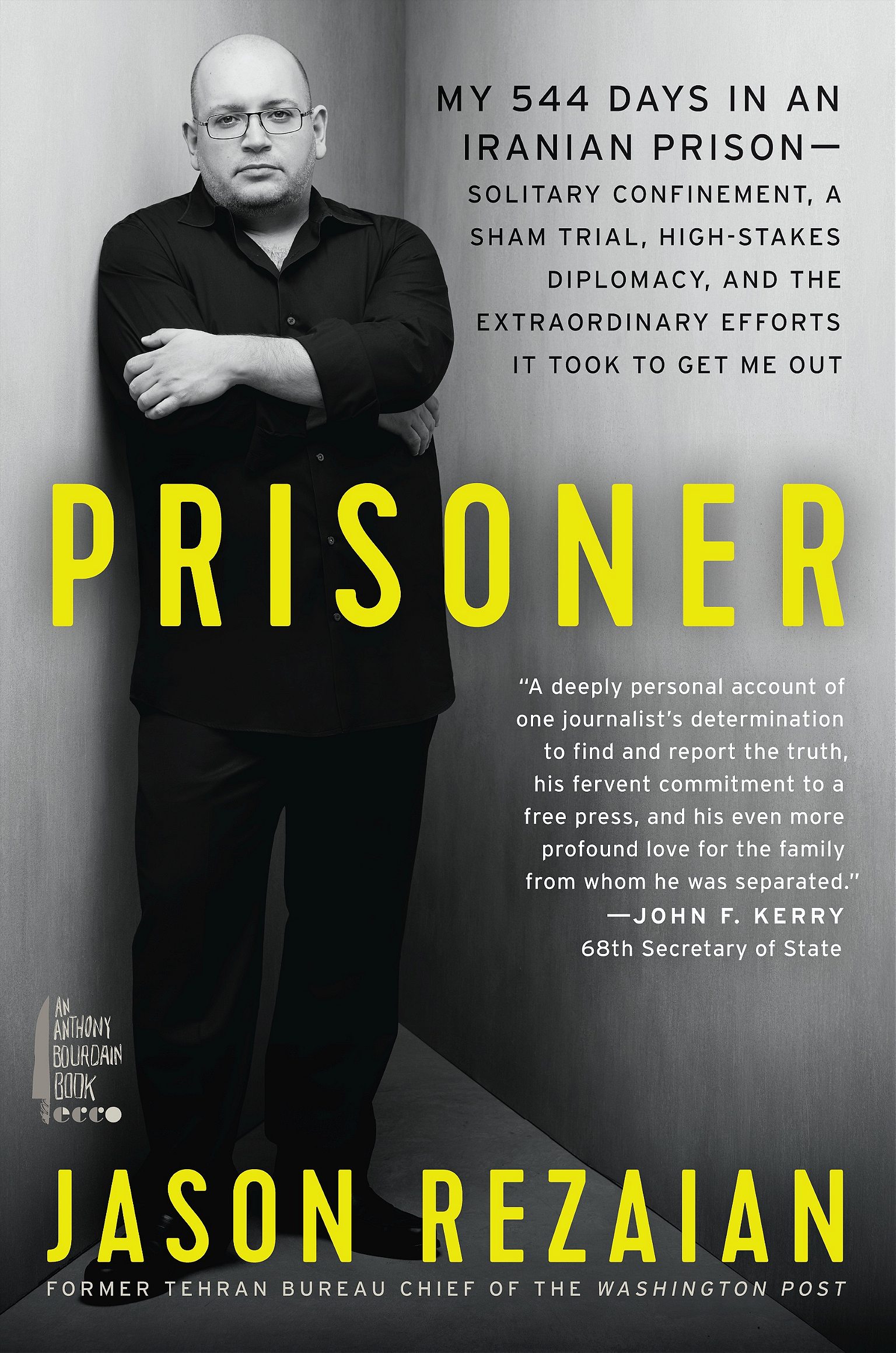

I met Jason in his midtown NYC hotel during his book tour to talk about his book, Prisoner: My 544 Days in an Iranian Prison—Solitary Confinement, a Sham Trial, High-stakes Diplomacy, and the Extraordinary Efforts It Took to Get Me Out. It was a whirlwind of publicity for he and Yegi that brought him on Fresh Air, Face the Nation, and more. I’m honored to have gotten so much of his time during that week, but then again that’s just the kind of guy he is.

Here is an edited and condensed version of Nathan and Jason’s conversation from this week’s episode. You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Nathan Thornburgh: I really brought out all the stops for Jason Rezaian. We got two cans of red Coke because there is nothing about Dry January that says I can’t drink phosphoric acid, right?

Rezaian: Exactly. Yegi says it doesn’t go with my book tour diet. But we’re going to make an exception. The taste of my childhood right there.

Thornburgh: There is a significance to the Coca-Cola. It’s not just a random bit of junk beverage. It’s a very special bit of junk beverage for us to sip on while we talk about Prisoner—an incredible book that took me to some places I’d never been before.

Before we get into the book, let’s go back to before you became the eponymous prisoner, your earliest days as a correspondent in Iran. As you point out in the book, you were a very unusual creature in the journalistic landscape: an American with kind of full press accreditation inside Iran.

Rezaian: Yeah, I went there for the first time in 2001. I grew up in a predominantly Iranian family in Marin County. So, I knew something about the culture. My dad came to the U.S. in the late 1950s and he started traveling back to Iran in the late nineties. The first time I went to Iran was 2011. I knew that I wanted to write from Iran. I didn’t know if anyone was going to be interested in what I had to say, but I just figured if I keep trying, if I keep going for it, I’ll have this opportunity. Because there are so few people who are able to write in English and really have an understanding and awareness and are able to try and explain a country that we’ve decided is the most evil country in the world to an American audience. I understood both what America has against Iran, but I also know what Iran has to offer the world and how we get it wrong. Look, the Islamic Republic is a bad regime. There’s a lot of bad regimes out there and Iran is one of them. I took that as a starting off point and wanted to just show this place in all of its nuance and all of its color.

Thornburgh: So you’ve been working to show the nuance of Iran, and you get arrested.

Rezaian: Yeah, I had this sort of deep feeling inside that getting out of there was not going to be an easy maneuver. It’s not just gonna be like, “Alright. Here you go. Here’s your stuff. Go home.”

Thornburgh: It was nuts for me. You became a version of every journalist’s worst dream come true for 544 days.

Rezaian: You never want to be thrust into the middle of a story.

Thornburgh: Tell me about that day that you and your wife, Yegi, were arrested.

Rezaian: It was hot. It was Ramadan. We were preparing to come here to the United States to collect Yegi’s green card. We’d been married for about 15 months, and we were on the cusp of starting that bi-continental life that a lot of journalists envision for themselves.

Thornburgh: So, you were preparing for that trip, but you already sensed that there was some weird stuff happening and Yegi was trying to hustle you guys out of there, right?

Rezaian: Yeah. There was some activity on our email accounts and social media accounts. We’d been hacked. The passwords were changed. We weren’t sure if it was normal hackers or more of the state variety. I think Yegi was way more in tune with the fact that this could be something pretty nasty than I was because she grew up in Iran and you hear stories about people disappearing and bad shit happening. So, they showed up and hauled us away to prison that night.

Thornburgh: I don’t want to dwell too much on your imprisonment, because people need to just read the book, but the one thing that really just struck me was the sense that you got stronger throughout the process. And this is a very long process—544 days in total. Your strength and resolve kind of built up over time, and I think for anyone who hasn’t heard about your story or hasn’t read the book yet, that would seem very counterintuitive. How did that happen?

Rezaian: It wasn’t as though the strength started building on day one. I mean that period of solitary confinement is a breaking down of your psyche, of your morale, of your personality until you’re really just a scared animal. You sink back into corners. That feeling never really away during that entire 544 days, but over time you start to latch onto things that make you a little bit more comfortable. At one point, I realized that three months earlier, they said that my execution was imminent and then nothing happened. Then they said that I was going to be here for life, but now they’re letting me exercise a little bit. Why the hell would they let me exercise if they are not worried about my health? It also that helped that I was able to occasionally see my wife, and to talk to her, and to have her in my ear saying, “Hey, you know you’re going to go on trial at some point and the last thing you’re going to do is plead guilty because you didn’t do anything wrong.”

I knew that I did have some cards to play.

Thornburgh: That’s why we’re drinking these Coca-Cola. That was part of the process. After you got out of solitary, you and your cellmates were actually able to eat pretty well (and have things like the occasional coke).

Rezaian: Yeah. My cellies were both well-established characters and you know, in most places in the world, if you go to prison and you have money, you’re going to have a better experience.

Thornburgh: You guys got a little stove.

Rezaian: Yeah, a little electric Bunsen burner that they would take away from us for weeks on end, just to fuck with us. They would give it back and then they would take it away again. Sometimes, our families would bring money to the prison door because we had accounts. The jailers would bring a piece of paper once a week that says you have this much money to spend. In the beginning, I’d say that I need some fresh vegetables because if I don’t have some of that, I’m going to get scurvy and I’m probably not gonna make it. Over time you kind of push the envelope a little bit, you know. I want some eggs. I want some meat. They would push back and say no. Then you’d say that you’re going to go on a hunger strike, which is really the ultimate desperation move in prison. I learned over time that I was an important prisoner.

Thornburgh: The relationship between you and your “experts” as they’re called, which is the creepiest fucking thing,

Rezaian: That’s what they call themselves.

Thornburgh: Right. But I mean, just the idea. I’d never heard of an interrogator referring to himself that way, and it just gives you a little glimpse into their mindset.

Rezaian: Exactly. They have a kind of deep-rooted belief that they’re on God’s side, and God’s on their side. So, whatever they’re doing must be right.

Thornburgh: But you and your wife knew the law of the Islamic Republic of Iran better than these jokers.

Rezaian: For sure. We had help with that. Yegi had a lawyer that was advising her outside, and one of my cellmates, a Sunni Kurd who had been in prison for several years, was able to buy the entire penal code of Iran. I think the jailers gave it to him because they knew he wasn’t going to get out soon. He had this stuff memorized and he would tell me, “They can’t do this to you. You have to ask for this. You have to push for that. When you go to this court session, the first thing you need to say is anything that you said during interviews or interrogations was told under duress and under psychological pressure. You have to say that you’ve been psychologically tortured.” I just went with it. You know you realize that you’re in a process that’s total horseshit. But at the same time, you’re in that process.

Thornburgh: There are moments in the book where the raw emotion of how you or Yegi responded to the situation really comes through. It feels like your tormentors are always trying to congratulate themselves on what they’re doing. You two don’t get to go back to Iran under current the regime, which has been there since 1979. There’s no happy ending in the way that it might’ve seemed in the news media, which wanted to just kind of move on from your story.

Rezaian: Yeah, it’s so much more complicated than that. The path of destruction that they created for my family and me, specifically for my wife and her family, is something that we can’t ever undo. Are we happy that we’re free? Yes. Are we happy that we’re healthy? Of course. Are we happy that we have opportunities and we’re putting our lives back together? Without a doubt. But at the end of the day, the life that we’re living right now is not the one that we had envisioned for ourselves. The personal effect that [this experience] has on us is just so fucking devastating. That’s the part of it that I hope that people, and leaders in that country, take away when they read this book because fuck them.

Thornburgh: Yegi was working as a journalist at the time you and she were jailed.

Rezaian: She was working for The National.

Thornburgh: The two of you had contributed so much to journalism from within Iran. You two were reporting on what Iranians want and love and believe and hope for. You and Yegi had value in that sense.

Rezaian: Not only were our pens silenced, but the reporters who are still in Iran are much more timid. It’s not a coincidence that the number of bylines from Tehran has decreased dramatically over the past three or four years. That’s really sad. This is not one of these things where it’s America’s fault or the American media’s fault. This is the Iranian leadership’s fault. For years, Iran’s been complaining about the country’s perception around the world. Why do they say this about us? Why do they say that about us? Well, you know what, you just closed the door on [positive] press for a very long time.

But my great hope, still, is that the people in that country are as a society moving in the right direction, even with all of the impediments that have been placed on them by their own regime.

Thornburgh: There’s a larger story in your book beyond your personal experience that is very much connected to things that we’re starting to see on our soil. This is an important story for a reason right now.

Rezaian: I hope that it’s instructive. So many of the things that have happened [since I was arrested], we could not have predicted. I mean, the whole case with Jamal Khashoggi—his murder and the horrific nature of it just brought so many things back front and center for me. Doing this job, I don’t feel 100 percent safe in Washington DC. People who don’t work in this industry sometimes look at me kinda funny when I say that. People that do can kind of feel that tension. I’m nervous about what the next few years hold for this country. I think we’ll get past it. We have to get past it. But overall, I don’t feel like we’re particularly on solid ground right now.

Thornburgh: We believe in the idea that food is a commonality or a desire that you’ll see in people anywhere in the world. There’s something else that ties us all as humans, and that is the capacity for our systems to go totally fucking haywire. The Islamic Republic of Iran could be us. And there are people who are actively trying to create that here.

Rezaian: Yeah. One would hope that the foundation is solid. Look, if we have a massive financial overhaul, or whatever we called it in 2008—if something like that happened again, I’m not so sure how well we would get through it in terms of our systems, our traditions, our values, and things that we’ve kind of just accepted as fact in my lifetime. That’s a scary thought.

Thornburgh: That’s dark, man. Jesus. Let’s go back to that part where you were bullish.

Rezaian: My dad passed about eight years ago and he used to tell me, “Son, if you worry, you’re gonna die. If you don’t worry, you’re gonna die. So don’t worry.”

Thornburgh: That’s good. That’s as bullish as we’re going to get. Alright. Jason, it’s been a pleasure knowing you. Reading this book has just a kind of blown my mind. I thought I knew this story, but to be perfectly honest, I had no idea. It’s incredible. People need to read this book.

Rezaian: And they should have a couple of cans of Coke with them while they read it.

Thornburgh: They’ll get jacked up. Thank you to you and Yegi for your friendship, and thank you for being a hell of a writer and for going through the process of putting this out there.

Rezaian: It’s been a struggle, but having friends like you and having the opportunity to talk about our experience is a really nice thing, so thank you.

You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Episode 25 Show Notes:

Jason’s harrowing book

Joel Simon’s book. You should buy this as well!

We Want to Negotiate: The Secret World of Hostages and Ransom

Michael Scott Moore’s account of his kidnapping

The Desert and the Sea: 977 Days Captive on the Somali Pirate Coast

Evan Ratliff’s latest

From the closing notes

Mansi Choksi’s guide for Roads & Kingdoms.

16 Things to Know Before You Go to Mumbai. If you’re going to Mumbai, you must read this. If you’re not going to Mumbai, YOU STILL MUST READ THIS!

Up Next

A Life in the Commune with Tanja Fox

Beyond War with Yuri Kozyrev

Drinking coffee in Moscow with one of the great conflict photographers of our time.

Instant coffee in Galway with Matt Orlando

Nathan Thornburgh and star chef Matt Orlando of Amass Restaurant drink lousy instant coffee in Galway and talk about running a true zero-waste kitchen in the age of greenwashing.

Punking the Paiche with Michael Snyder

Journalist Michael Snyder talks with Nathan Thornburgh about an invasive fish called paiche in the Bolivian Amazon.

Could A Scientist’s New Soil Treatment Solve Desertification?

In a small dry corner of England, Aquagrain is creating a super-absorbent biodegradable hydrogel that could help crops grow in degraded lands. Aquagrain is a finalist for the 2024 Food Planet Prize.