In Beijing, a public park is a prominent hub for seniors seeking new life partners. Lavinia Liang meets three of the park’s seekers.

In the eastern part of Beijing’s old city, between the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square, lies a narrow strip of park running from east to west, bisected by Nanchizi Street. The river that runs through the park is the Jinshui River from Tiananmen Square. But on this stretch of land, it’s called Changpu River. The park, only 200 meters (656 feet) long, is Changpu River Park.

The small park is quiet, sheltered from the bustling Tiananmen Road (which requires an underpass for pedestrians to cross) by a large, red wall. It’s a tranquil place for visitors to Beijing’s most-frequented attractions to stop and take a rest, and nice for a short stroll.

But on Tuesdays and Saturdays, the park is more than that: it’s a prominent hub for the divorced, middle-aged, and elderly seeking dates and new partners.

Nobody seems to know how or why Changpu River Park, which opened in 2003 after restoration, became a dating spot, but according to the park’s participants, it spread quickly by word of mouth. The majority of those who frequent the park are in their 60s and 70s, although there are outliers on either end, including those well into their 80s. In my trips to the park, I encountered a good number of divorcees, as well as widows and widowers. There are also those whose partners are chronically ill or debilitated. Others still, a minority within this minority, are those who have never married.

China is facing an unprecedented aging population. In 2017, those aged 60 and above numbered 241 million, or 17.3 percent of the population, and the country’s National Working Commission estimates that, by 2050, China will be about double that—just under 35 percent of the overall population. And the country’s last census, in 2010, reported over 52 million single Chinese retirees, with at least 6 million of this group being widows and widowers.

Today, many older Chinese seek companionship through “plaza dancing” or communal singing and other public activities. The dating scene at Changpu River Park takes this a step further. I got to know three Changpu River Park seekers, who told me what brought them there, what they’re looking for, and their experiences with the space’s dating scene.

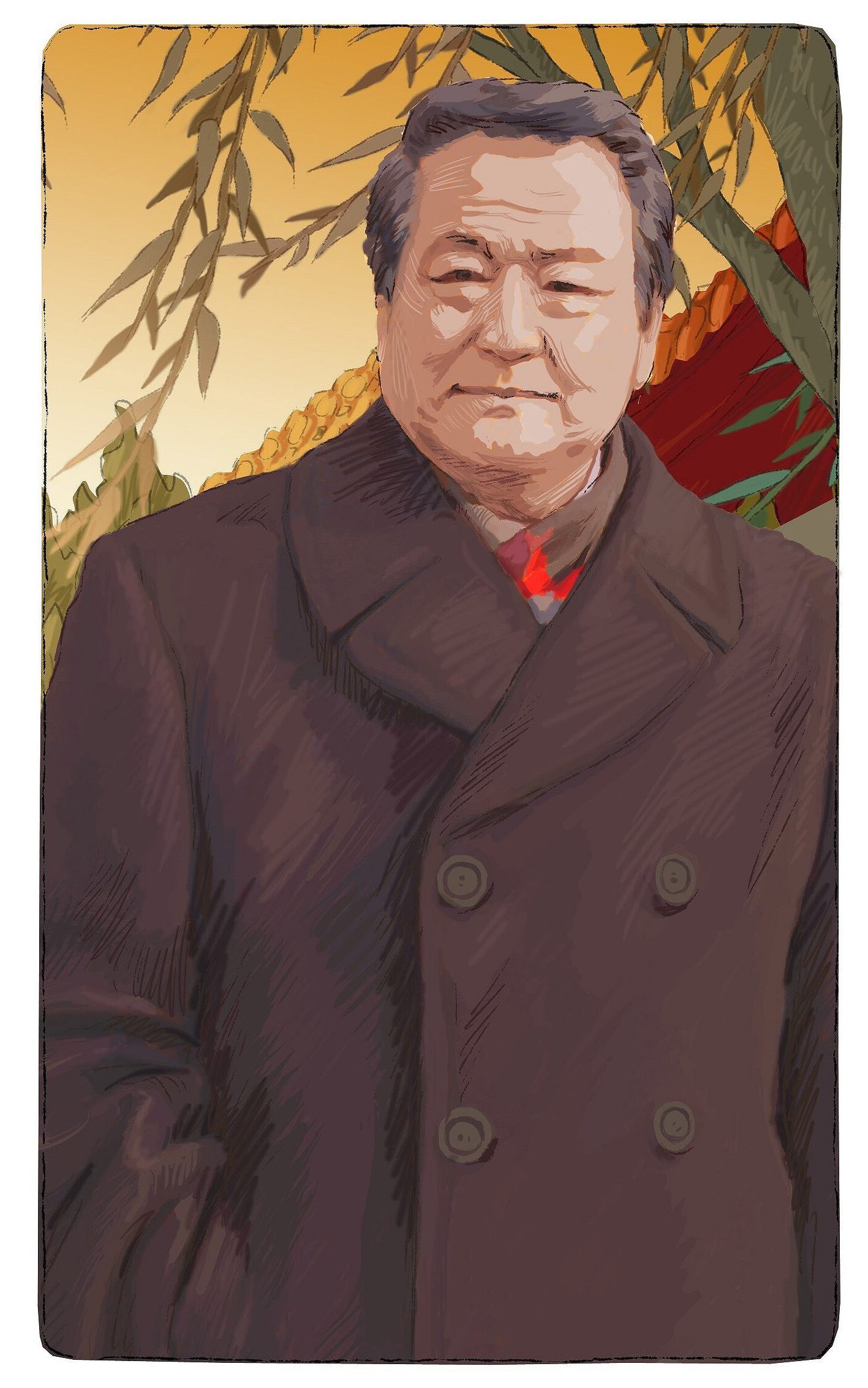

Mr. Shan

On a noisy January Saturday, a man in a dark gray peacoat stood apart from the crowd, on the edge of a concrete plaza, dangerously close to the river. He was the only person wearing such a coat—rather than the brightly colored plumages of cotton-padded mian ao and down-lined yurong fu in the biting cold of northern China. His hair, though thinning, was carefully swept to the right. His gaze panned across the groups of people gathered around the ornately-colored veranda, or lang, on the eastern side of the park, where all the action takes place. People smoking in small circles; exchanging WeChat contacts with each other by the water. A few passersby struck up a conversation, but for the most part, Shan stood apart from the rest of them, hands stuck in the pockets of his wool coat, his face partially obscured in the bright morning light.

“I’m seriously here to look for a new partner,” Shan said, casting a quick glance over the rest of the crowd. “I am, at least.”

It was about ten in the morning, going on eleven. Someone had set up industrial-grade speakers on the widest part of the plaza, and a few people were warming up to dance. Shan was referencing a common quirk in the park, where many who come say they’re only here “for fun” or “for a stroll,” when in reality they’ve made a deliberate decision to come on a Tuesday or a Saturday.

Shan, in his early 60s, is from Xicheng, the western part of Beijing’s old city. He used to work in chemical processing for the government.

“Tie fan wan,” he said, laughing. “You’ve heard of that?” which translates literally to: a metal bowl sort of job. It’s what the Chinese call government jobs, which guarantee stability and pension, even if they don’t promise riches and glamor. You can’t break a metal bowl.

His daughter is in her thirties, married, and working in the same department where he once worked. Shan and his wife waited for their daughter to become an adult before they filed for divorce. “We didn’t want to put that over the children,” he said. “It just didn’t work out.” He shrugged. “No bad feelings.”

But Shan knows that divorce can still be an uncomfortable topic—at least among his generation. For a long time, divorce in China was perceived as more than simply a failed marriage—it’s a failure of duty to one’s family, to playing properly the good son or daughter or parent. “Very few,” Shan said, referring to the number of divorced people in China. “Very few.”

And yet the reality isn’t actually as barren as Shan perceives it to be. China’s “crude divorce rate” (the number of separations per every 1,000 people in the country), while not among the world’s top ten, isn’t particularly low. In fact, year after year, it continues to grow.

Pei Xiaomei, Professor of Sociology and head of the Research Center for Gerontology at Tsinghua University, told me over the phone that the stigma of divorce in China really only holds true among this older generation. “If you look at divorce rates for those born in the 1980s and 1990s, you’ll find that divorce is now so frequent,” she said. She added that these rising divorce rates aren’t the result of anything cultural, but simply symptomatic of modernization.

Pei added that China’s growing tolerance towards divorce has a particularly gendered history. In the 1950s, when today’s elderly generation was young, divorce wasn’t just a question of public opinion, but a question of morality. And while men were frowned upon for divorcing, the backlash against divorced women was a lot worse. Pei said that things started to change in the 1980s, when women were granted more freedom, and were able to move to cities and seek jobs of their own.

But traces of gender discrimination still linger. Men are at an advantage for remarriage in their later years, Pei pointed out, since China has more aged women than men (because women outlive men everywhere in the world.) “And yet the media, when they cover this—when they cover loneliness—they are almost always talking about the males, not the females,” Pei said. “As though the female elderly don’t also have these demands, these needs.”

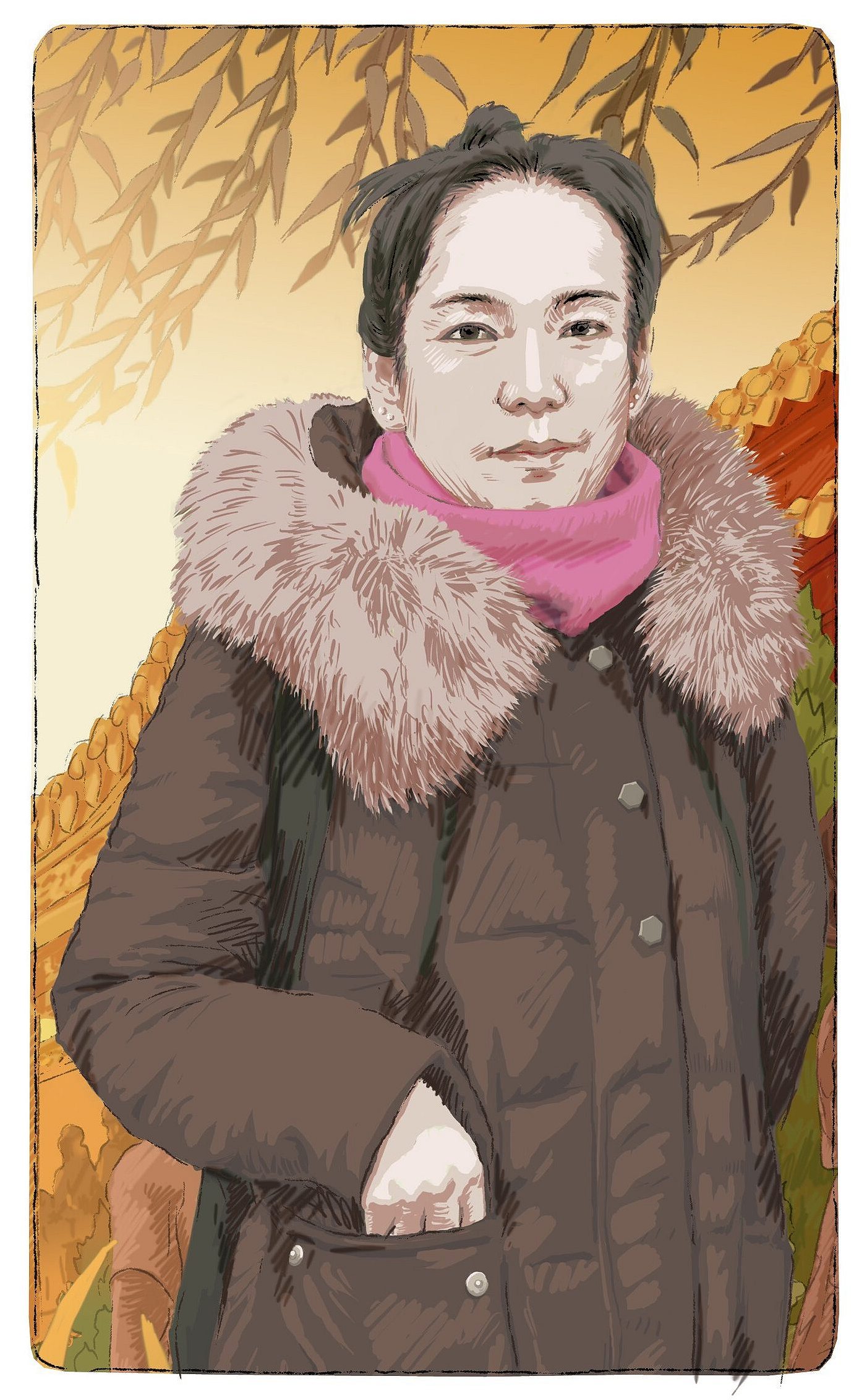

Mrs. Li

“I was so embarrassed,” said Mrs Li, pulling her face mask down to get a better look at the sparse pickings at Changpu River Park on a Tuesday. A few men, all walking alone, many with their hands clasped behind their backs, wandered about at safe distances. They avoided eye contact with Li, who stood at the center of the park, rubbing her gloved hands together.

Li, with her hair between pixie and a bob and heavy eye makeup, seemed younger than the men hovering on the edges of the park’s main plaza. Li, 55, is a journalist and editor from Shenyang, the capital of China’s northeastern province of Liaoning. She and her husband separated 12 years ago, and although Li has some family in Beijing, including a son and daughter-in-law in their early thirties, Li is drawn to places like Changpu River Park to find potential companionship.

“Everyone told me that, at my age, I shouldn’t keep looking,” she said. “But a few years ago, I was very sick, and there was no one to take care of me. That was when I realized that having a significant other is important in a different way as you approach old age.”

Li remembered her first time at Changpu River Park being difficult. Her Beijing-based niece had encouraged her to go.

“I was so embarrassed,” she said. “I thought, is this what I have become?”

That Tuesday, Li was waiting for a train to go back to Shenyang, where her work is still based. She comes down to Beijing often to see family and, this time, she thought she would loop just once more through the park, which was on her way to the station.

“Last time I was here, the men examined me like I was a specimen or something,” she said, and again surveyed the mostly empty park. It was emptier that day because it was a weekday. It would surely be livelier on the following Saturday.

The seekers—at least the men—waste no time at Changpu River Park. The directness of the park’s system was another source of embarrassment for Li the first time she experienced the park. Seekers directly ask each other, Are you here for dating? And if the answer is yes (because there are always those who claim they’re just there for a stroll), they’ll then run through a whole gamut of basics before any proper “dating” can take place. Chief among these: age; residency or hukou status; income (or pension if they’re retired); the age and marital status of their children. Unmarried children can be a potential financial burden.

Li also noted that women of her generation are still often quite traditional, despite nominal gender equality in contemporary society. Women are still seen as aggressive if they make the first move; women are still encouraged to be approached rather than to approach.

“I’m quite lonely,” Li admitted, also confessing that she doesn’t expect much from a place like this. “And I can’t go live with my son. He has his own life, and his own family to come.”

What about other ways to meet people, such as dating apps? WeChat, an all-in-one social media and messaging app, dominates connectivity in the country, and approximately 83 percent of the country’s smartphone users use it. Smartphones are universal. So why not stay in the comfort of one’s home when seeking new life partners?

Li shook her head. “At least you can see what they’re really like, here, in person.”

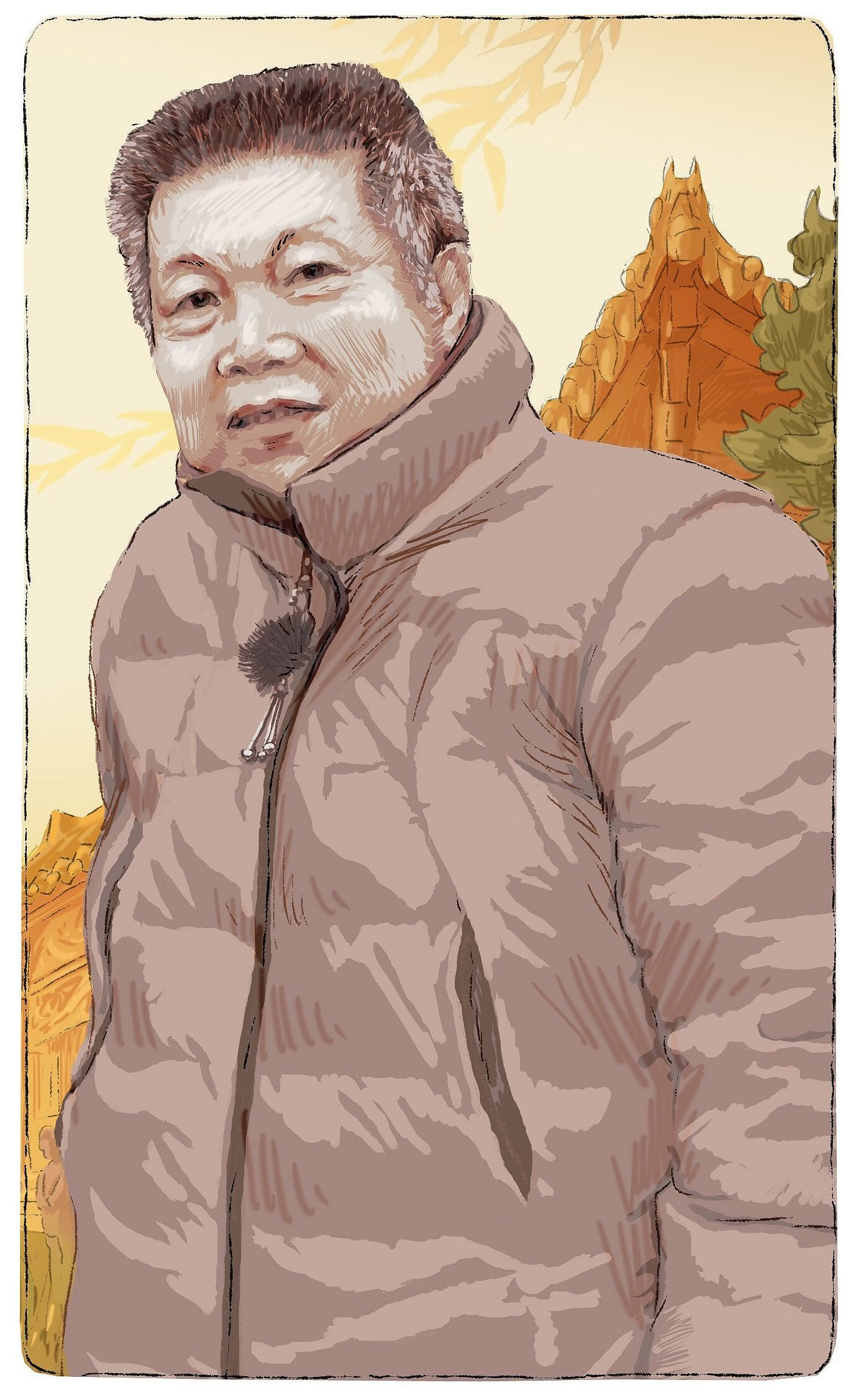

Mr. Liu

The man in the banana-yellow down coat was loud, and, judging by the ring of friends around him, a popular regular. His hair, more silver salt than pepper, was cropped close to his head. He lit up a cigarette, and some in the group around him followed suit.

“What do you mean ‘why are we here?’” he barked. “We’re here to have fun, of course… If we find someone, then so be it. But otherwise, it’s fun to come here, take a loop.”

Although the park was bustling that Saturday, Liu commented that the park could get even fuller, especially in the summer. He took a long drag on his cigarette. “There’s more Beijingers in the winter, too, because all the wai di”—people from other provinces; here, meaning any non-Beijinger—“start returning home for the holidays.” He leaned in closer, although his voice never lowered in volume. “Most of the women who come here are wai di. Most of the men are from Beijing.” He is also a Xicheng native.

Liu, on the cusp of his 60th birthday—and national retirement age—has been married four times, and has dated seriously a few times through Changpu River Park, too. He was married to his first wife for two years, his second for three years, his third for 14 years, and his fourth for eight years. He married his first wife when he was in his 20s, and it all just “sort of went from there.”

Why did he get married so young? “The same as anyone,” he said indignantly. “You think it’ll be fun. You’re young and you think it’s love and you get married and then it doesn’t work out. I don’t talk to any of them anymore, but we’re not on really bad terms, not really.”

Liu has been coming to Changpu River Park for the last few years whenever he gets a chance, and now seems to know the scene pretty well. He gets straight to the point with the women he talks to—the sort of exchanges that Li so hated. Liu doesn’t believe there’s anything to be embarrassed about if you’re already at the park.

Liu walked over to a woman in a puffy, iridescent blue coat. “This is my girlfriend,” he yelled proudly. They’d been seeing each other on and off, mostly in the park, for a few months.

She was petite, with a small face and large eyes. Like Li, Liu’s girlfriend was from the northeast. She was in her 40s, from Heilongjiang, China’s northernmost province, and had come to Beijing to find work as a teacher.

She said that Liu had approached her when they first saw each at the park a few months ago, and that she had kept talking to him because of his demeanor and his confidence in himself. “He’s very open,” she said, choosing her words carefully. Liu couldn’t say exactly what had attracted him to her in the first place, just that they’d hit it off. A quick scan of the park affirmed that she, in her 40s, was one of the youngest people there.

With all his own past relationships, Liu acknowledged the quiet stigma that being divorced can present.

“Yeah, and? What’s the percentage of divorced in America?” he asked, scratching his ear. “One-third? One-half? I know it’s a lot.” He said this with a dismissive wave of his fresh cigarette.

Liu and his girlfriend aren’t exclusive yet. Will they ever be? “We’re just here for fun,” he repeats. Maybe? Only time—Tuesdays and Saturdays—will tell.