A primer on traveling well in Russia’s swaggering capital.

If you had visited in the last days of the Soviet Union, and then returned to live in the mid-90s, as I did, then you could be forgiven a bit of heartbreak for Moscow and the people who lived there. The radiant enthusiasms of perestroika were gone by 1995, murdered by crony capitalism or the disastrous Chechen wars or their shambolic boozehound of a president. Moscow had always been the epitome of Russia, but for a long period, that simply meant that the city was crueler, less equal, more chaotic and dangerous than it had been before.

All of that seems now a distant memory, as if scrubbed clean by one of those maniacal sidewalk-water-Zambonis that pressure-wash the sidewalks of the city center every night. Central Moscow now is repainted and so clean it can feel like Slavic Disneyland. It’s a perfect reflection of Putin himself: pinched, wealthy, disciplined. God help you if you’re an outspoken artist, a disgruntled activist, a run-of-the-mill fall-down drunk or some other kind of undesirable. Moscow has no place for you these days.

I have no nostalgia for the old chaos, though. Life in Moscow is easier these days, especially for visitors. The streets are safe at night. Russians are, despite what you might have heard, enthusiastic hosts. The grand buildings and bejeweled churches gleam everywhere. And thanks to a falling Ruble, prices are reasonable across the board. This is actually, despite all the geopolitical burbling, an excellent time to visit. — Nathan Thornburgh

Save up for your Visa. The price of a Russian tourist visa keeps creeping up, and the requirements—like needing an official invitation from an approved organization —remind one just a bit of the Soviet days. If you stand in line at a consulate in the U.S., you can get a visa for US$123. If you use a passport service and need a quick turnaround and expedited visa, that can creep up to nearly US$500. It’s absurd. Although, importantly, it’s not nearly as egregious as what many have to go through to visit the U.S. Good news for World Cup ticket-holders: you can enter Russia without a visa if you have a Fan ID, which gets you free public transportation as well.

[Already been to Moscow? Here’s R&K’s guide to Saint Petersburg.]

Don’t fear the Ruble. Moscow used to be expensive. Like, weird-expensive. Luanda-expensive. But with the Ruble being one of the first currencies to go down the slide that we’ll all be on soon enough, this is actually a great time to visit. A quality hotel in central Moscow can be yours for US$110/night or less (except during the World Cup of football, aka the Beautiful Gouge). Moscow is still a city where people spend to make a statement, so you may find yourself with a heavy dinner bill if you aren’t careful, but even the very highest-end restaurants like White Rabbit don’t cost what a pedestrian upscale meal in New York might.

Download some Russian. Moscow is far more English-friendly than most places in Russia, but without at least some basic words and some translation firepower, you’ll struggle at times. Download Yandex Translate [Apple//Android], which works offline too and translates text from photos. (It has 94 languages so you can use it for future trips, too.) Here are the Russian words you really should know: выход (VY-khod) exit; вход (v-KHOD) entrance, ресторан (resto-RAHN) restaurant, туалет (tua-LYET) toilet, аптека (ap-TYEK-a) pharmacy. And, for good measure, something weird and local like ботва (baht-VA), which means the leaves and stalks of root vegetables or tubers, but is used as slang for nonsense or a trifling.

Carry your passport. It’s unlikely that you’ll get stopped by police, who mostly seem to stand around waiting for opposition leader Alexei Navalny, but if you do, you’ll definitely want to have your passport on you. Take it with you at all times.

Don’t drink the water. The water system here is better than in rickety Saint Petersburg, but bottled water is still king.

Go small with cash. Carry a wad of cash, because not everywhere takes credit cards (and almost nowhere takes American Express). And as is true of Russia generally, make sure you get plenty of small bills (100₽ and 500₽ notes) and not just a lean stack of 5,000₽ notes that no one will want to break for you.

Know your Rings. Russia’s eternally autocratic tendencies have deeply shaped Moscow. Moscow is the heart of Russia, and the Kremlin is the heart of Moscow, so the entire city spins out from the ancient fortress in a series of concentric rings. The first ring—the Boulevard Ring—is actually more of a horseshoe, but the Garden Ring after that and the Third Ring Road trace great looping circles around the capital. The Circle Line of the metro does the same underground slightly further out from the Kremlin than the Garden Ring.

For visitors, this means the sweet spot for accommodations is probably between the Boulevard and Garden Rings. Further in, and hotels get more expensive. Further out, and you’re going to be far from everything—Moscow is a big sprawl. If you are saving money by being a bit further out, just make sure you’ve got easy Metro access. Moscow traffic will break your spirit, no matter what ring you’re on.

Git your Teremok. Moscow may be the city that went mad for McDonald’s, but Russian fast-food chain Teremok delivers a real hit of flavor and sense of place for a reasonable price. We will always enjoy the ability to get a buttery blini with roe for under US$10, or even this thing, which they call an E-mail Blini and which comes with mushrooms and melty cheese, like all email should.

Get that Rideshare. Moscow’s informal cab economy in the late Soviet days and throughout the 1990s was strong. Civilians of all kinds would cruise around in their personal cars and look for people flagging them down on the side of the road. For drivers, it was a way to make some much-needed cash. For riders, it was chaotic and sometimes tricky (you had to negotiate your fare and watch your back), but incredibly convenient. As ambivalent as we are about ridesharing around the world, it is a lifeline in Moscow. Thanks to the ubiquity of Uber and Yandex Taxi (which recently acquired Uber’s Russia business), the good old days are back: only now instead of waving a couple fingers toward passing cars, you just tap on your phone and a (licensed and registered) car will whisk you away. Prices are similar in both apps and low by European standards (a 15-minute ride can run $6 or less).

Go underground. Moscow’s larger avenues and streets don’t have pedestrian crossings, so don’t keep walking, expecting to find one at the next corner. Instead, the city’s networks of underground passageways are how you navigate your way across the street. It can take a while to get your bearings underground and figure out which exit you need: some of the larger hubs are like underground cities and have a dozen or so. These passageways are also centers of commerce: you can buy clothes, groceries, get your watch repaired, etc.

Make friends over meat pockets. Cheburek is a delightfully greasy oversized crescent of meat-filled pastry that the Tatar people brought to Moscow. Cheburek Friendship (Чебуречная Дружба) is a somewhat oddly named purveyor of these delights. It’s a brilliantly humble place, with fluorescent lighting and communal sinks for washing your hands before and after. It’s just 40₽ (US$0.64) per cheburek. Also, you’ll want to get some vodka in you as soon as possible in Moscow, and you can definitely do that here: savvy (or just alcoholic) patrons chase each fatty bite with a swig of vodka followed by a gulp of Fanta. Our kind of place.

Find Ivan and his offal. There are plenty of restaurateurs in Moscow, many of them slick operators with a consistent, glossy portfolio of market-tested dining concepts. Ivan Shishkin isn’t like that. He’s an old friend of Roads & Kingdoms and one of the true iconoclasts in Moscow’s dining scene. His two main restaurants are Delicatessen (a basement speakeasy with a nearly blasphemous food menu) and Youth Cafe (a restored bordello on Trubnaya with big, wild plates to choose from). For the quickest hit of Shishkin’s off-kilter genius, slink down the stairs at Delicatessen and order the fried calf brains in egg yolk sauce with pike roe, or get the caviar pizza or perhaps the horse tartare seared with a branding iron at your table. Eat, drink, and think: this is a man who embraces freedom wherever he can find it.

Head for Food City. You might think that calling Food City (Фуд Сити), an agriculture depot on the outskirts of Moscow, a “city” would be some kind of hyperbole. It is not. This is an entire cosmos (ok, that is hyperbole) of vendors and farmers and chefs and laborers and laypeople who all have roles to play in feeding a megacity. For any food obsessive, it’s well worth the 40-minute cab ride south to get there and walk the aisles of Moscow’s breadbasket. And because Central Asians dominate the labor of this industry, there is some of Russia’s best plov—inexpensive, fragrant rice steamed with spiced meats—and fresh flatbread served at stalls on the fringes of the market. Think of it as a Tsukijii Market for vegetables and Uzbek rice.

Be caviar savvy. The ancient species of Caspian Sea sturgeon whose beloved roe has fed Tsars and peasants alike is endangered, and it’s illegal in Russia to poach or sell wild, black caviar. (Although this hasn’t stopped people from smuggling and poaching in all kinds of creative ways, including stashing 1,000 pounds of it in a coffin.) Most legal caviar in Russia comes from farmed Siberian sturgeon. You probably can’t know the source of every spoonful caviar you encounter, but if someone tries to sell you wild black caviar, it’s either illegal, not sturgeon, or a lie. If you want to drop some cash on excellent caviar and vodka in a restaurant, chef Ivan Shishkin recommends Beluga. If you want to score some top-end black gold and avoid the restaurant mark-up, try the Rybnaya Manufactura chain of seafood stores, or the admittedly pricier high-end grocers such as Eliseevskiy or the GUM shopping mall’s Gastronome No.1, where you can taste before you buy. You can also order online at Osetr, and they’ll deliver to you anywhere in the city.

Visit the Hotel Ukraine. Even if you’re not staying there. The hotel is now part of the Radisson chain, but they’ve left the original lettering intact from when it was the grand Hotel Ukraina, commissioned by Joseph Stalin and occupying the second-tallest of his gothic, Soviet power-showcase Seven Sisters skyscrapers. Come for the panoramic view from the very top of the hotel, reachable by separate elevator from the upper bar. Order a Moscow Mule—which was not invented in Moscow, by the way—at the terrace bar if you must, but this is a playground for karaoke-drunk oligarchs and cocktails are pricey. Whatever you do, don’t miss the diorama in the lobby—a 1:75 scale model of Moscow and the Kremlin complex, with a 5-minute audio spiel explaining what’s what. It’s a lot of fun, and a perfect introduction to Moscow’s heart. For an excellent view of the Kremlin, go to the roof restaurant at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel.

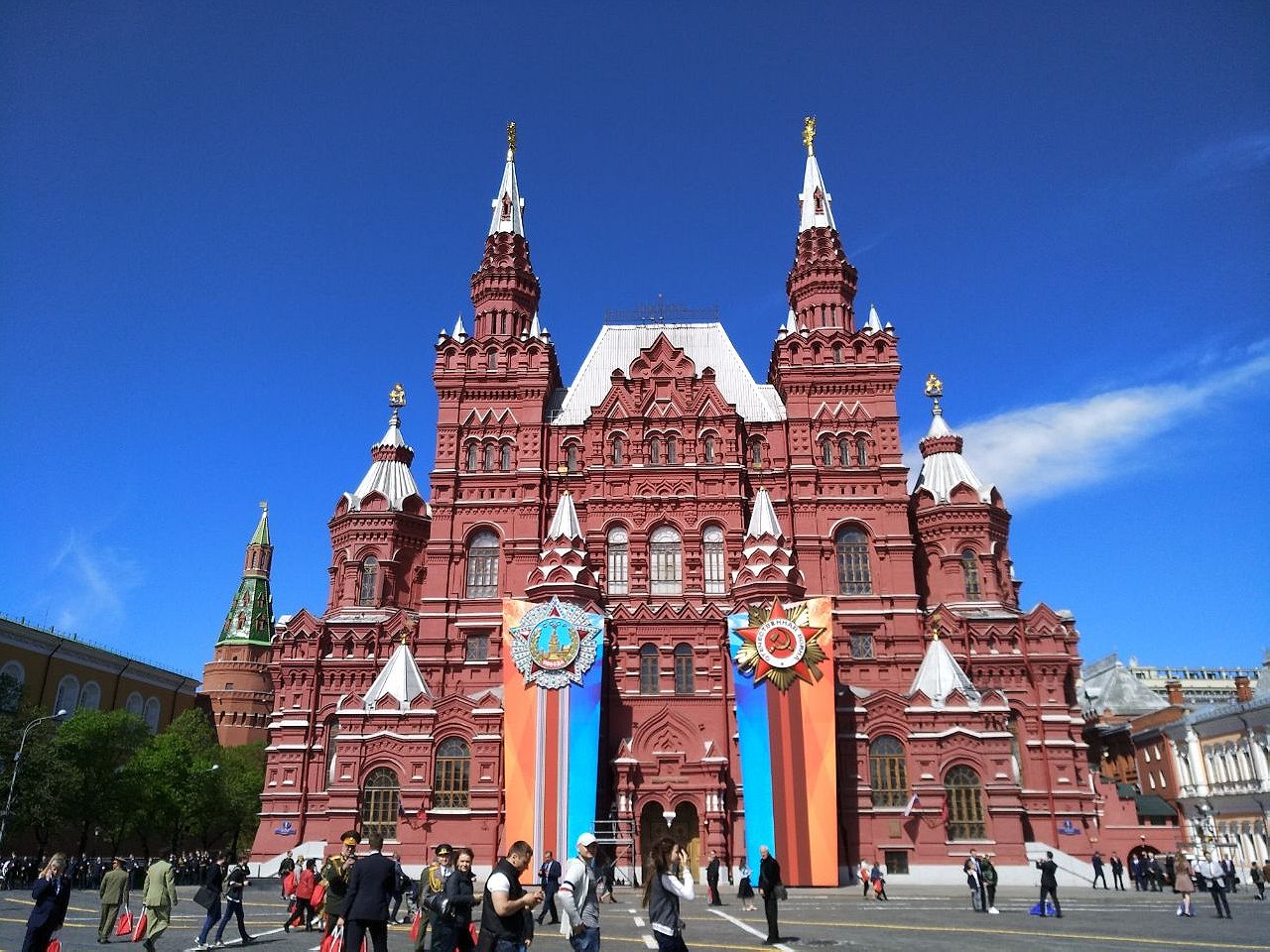

Join the masses at the Kremlin. As the beating fortress heart of Moscow, and therefore, all of Russia, the Kremlin complex and Red Square has a staggering share of Eurasia’s prime real estate, treasures, and historical artefacts—including Lenin’s Mausoleum (or strictly speaking, Lenin’s embalmed corpse). It will be busy, especially from May to September, so plan your visit in advance and try to go early in the morning. The Kremlin Armoury has a limited number of tickets available each day, for example. Booking tickets through the official Kremlin website will enable you to skip the ticket lines. When planning, avoid Russian public holidays: the museums might be closed, or busy with locals.

…then look beyond the Kremlin. There are world-class treasures and bling, naturally, but Moscow’s charms include dozens of obscure museums. There are scores of writers’ and poets’ houses (“The Master and Margarita” fans should check out the rival Mikhail Bulgakov House and state-run Bulgakov Museum, which are both in his former apartment building but don’t acknowledge each other); a vodka history museum; a museum dedicated to valenki (Russian felt boots); a gallery of working Soviet-era arcade games; an ice sculpture museum; and an opulent bunker built after the first round of nuclear tests. Note that some museums charge different prices for locals and foreigners.

But note that Monday is a day of rest… For Moscow’s museums, at least. Except for the Kremlin museums and St Basil’s Cathedral, it seems that Mondays are a universal day off for the keepers/houses of Moscow’s historic and cultural treasures.

Go to GUM for food, not the Chanel. Moscow’s landmark posh department store dates back to the 18th century, and is a barometer of sorts for the city’s consumption power. Its stores were more bare in the Soviet era, but GUM now has a full stable of upmarket chains. The real charm here is its food store, Gastronome No.1, which stocks the international and hyper-local product you need, such as Soviet candy. Also, try a deeply nostalgic Soviet-era ice-cream cone at one of GUM’s kiosks, and, finally, spend 150₽ for a most luxurious restroom experience in the “Historic Toilets.”

Tchotchke tip. If you must buy topless Putin calendars and nesting matryoshka dolls, then we recommend the little souvenir shop staffed by friendly Central Asian women on at Arbat 20, just between Dragon Tattoo and the Irish Pub. They have some schlock, of course, but a lot of high quality at decent prices—look for the matryoshki with traditional motifs of a farmwife holding a black chicken.

The Moscow Metro is your friend. Moscow traffic is some of the worst in Europe, if not the world. The Metro is cheap, fast, reliable, and gorgeous. It’s also not as complicated as it looks to a non-Cyrillic reader. Read our primer. Also, if you’re going traveling all over the city, you should get a refillable Troika card, good for all forms of transport: Metro, trams, buses, and suburban railways. (The card also comes in bracelet and key ring form for maximum convenience.) Now, go sort out your visa.