Alternative medicine in northern India.

As I sit on a big wooden bench waiting for Badkau, I don’t expect to see him walk in with something as ordinary as a bag of grapes. All the tales about Badkau are those of myth and awe, of supernatural healing and boundless expertise. I expect I will see what in Delhi we call a ‘farishta,’ an angel on earth.

But what I see instead is a tall, solemn man walking in carrying a bag of black grapes. I stand up, and with a shortage of things to say, I ask where these grapes are from. Are they special? “Nashik,” he says simply. Nashik, in the north of the state of Maharashtra, is known for its vineyards. It is where I expected them to be from. He gestures for me to sit down, and there I am in Kanpur, in a room with pink walls and a fan on full blow, in a place that is in no way medical.

“Nashik has all the wine of the world,” says an old man sitting next to me, beaming with pride, having found something to say to the middle-class girl from the capital. What about Italy, Argentina and Chile? “All the wine in the world!” he shouts again. This man, eccentric and oblivious to fact, is closer to what I expected. He tells me he is here to get his back fixed. Being the busiest seller of tomatoes in his neighborhood means dragging a cart around all day. This is, he tells me, not only physically dangerous, but can be a real mental strain. It is Badkau that keeps him at his job. Every day when he finishes, he comes to the clinic for relief. “Have you ever broken it?” I ask him. “Of course! Every day! But it was fixed in this room.”

Badkau means ‘balcony’ in Hindi, but is also slang for ‘big brother’ or ‘elder’. When I ask for his real name, all I get is silence. A man of calm temperament, Badkau tells me he cannot fix broken backs. He keeps them working, and keeps them healthy, but if they break, it is not in Badkau’s capacity to heal them. Often, he has to turn people away from his door: the terminally ill and old women with spinal injuries. He has to tell them that he is merely a setter of bones, not a miracle worker.

The process itself is simple, but requires calculated expertise. First, when a patient arrives at the door, he must tell of his ailment, or the general area where he feels pain. Badkau or his son then feels the particular area, searching for pinched nerves, broken bones, or swollen muscles.

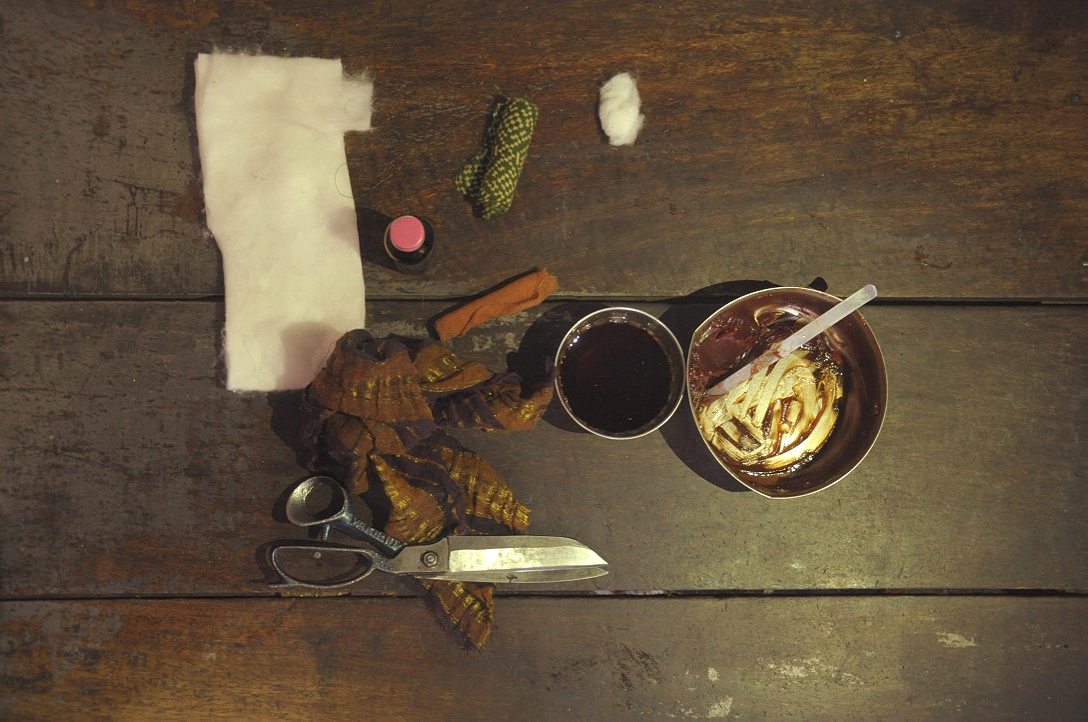

Depending on what they find, a dark, oily substance made from roots and herbs – bhringaraj, gooseberry stems, and raw ginger – is applied on the affected area. A bandage is applied with another oil, and smoothened out with an eggshell. The patient is then given physical exercises, your usual physiotherapy, which Badkau claims 90 percent of people forget about. It’s 30 rupees, or 50 cents an appointment.

The street outside Badkau’s clinic is swarming with believers. An old woman tells me he can fix insomnia: he did it for her son. Slowly, during a series of sessions, Badkau healed the nerves that were causing him to stay up all night. A sleepwalker myself, I remember going to an alternative healer after my parents had emptied their pockets in a series of appointments with psychiatrists.

My parents then, like many other Indians now, were financially and mentally incapable of adhering to Western medicine. No one knew what to expect from those little pills, shiny and glazed with promise. The words ‘instant relief’ had flown over our heads with deceptive appeal. The idea that something would immediately and mysteriously cure you was in essence, strange. Eventually, we grew into it, like the rest of the urban middle class, using terms like ADHD with nonchalance and popping Combiflam painkillers like they were boiled candies.

Kanpur sits on the banks of the Ganges in the west of Uttar Pradesh in northern India. With the exception of a handful of residual aristocrats, some adamant intellectuals, and a few loyal natives, more than 40 percent of the city’s population lives in abject poverty. The lack of medical infrastructure is just one of the problems that the city faces every day. Education, public health and infrastructure have been handled with disinterest by a series of governments. For decades now, a Kanpur-based activist and professor tells me, the city has been has been completely neglected by the state.

Almost absent from Indian history until the 13th century, Kanpur became an important trade center during the colonial regime. After defeating the Nawab of Awadh on the banks of the Ganges in 1765, the British realized the strategic importance of the city and began to build mills. Leather, textiles and cotton became some of the major industries of Kanpur, providing employment for almost all of its working class. The mills began to fall in the 1960s, and the last one closed in the 1990s. After that, unemployment rose and poverty spread.

Badkau, like most men of his generation, had worked in the mills. When he was laid off in 1962, he started working as a bonesetter, an art he had learned from his uncle as a child. “One must be born with a supernatural sentimentality to understand the bones of others,” Badkau says. “You have to be able to clear your mind and feel someone else’s blood and bones for a whole day. It takes a lot of discipline.”

There is a serious lack of trained doctors in Kanpur. Instead, there are unqualified quacks, making money off the majority of the poor, promising cures, and making incorrect diagnoses. A young boy in Badkau’s neighborhood is said to have developed pneumonia after visiting a series of quacks. Another woman paid for six months of hepatitis treatment without really knowing what hepatitis is. Apart from a handful of affordable, community-service clinics, reliable doctors are not easy to find. Badkau, therefore, is a figure of trust.

“I often just treat their head so they can calm down,” says Badkau. “People’s lives aren’t easy here. When they come to me with a few broken bones, it is my smallest duty to set those right.” Badkau’s clinic is not just a place of healing, but also an integral part of the community. Women hunch outside, waiting for friends to finish appointments. Men share the newspaper. Some people bring fruit or a pot of meat to share. The clinic unfolds into food and conversation.

Bone setting is a dying art. The men who practice it are of the strict belief that it is hereditary. Badkau’s neighbors, also bonesetters, guard an empty clinic and retain the air of failed businessmen. Pleasant in demeanor, they are constantly suspicious of me, ask if I am a tax checker, and tell me about the government sending the police to occasionally swindle them. In a 10-minute conversation with them, there is less talk of healing and more of money. “We tried to teach our kids, but they are not interested,” says one of the neighbors, a man called Aftab Feroz.

Small towns demand you talk to everyone you meet, and at one such meeting, someone points me to Gangaram. His home, also his clinic, is a small shed with two beds and a rickety wooden ceiling. As I walk in, the group of people who pointed me in his direction follow me inside. Gangaram is a more spiritual practitioner of bone setting than Badkau. When I ask him about his process, he smiles widely, and tells me it is a secret from the Gods.

After spending a few days with Badkau’s technical approach, Gangaram takes me by surprise. “When did you find out you were blessed?” I ask, skeptical.

“I was 26, and I sat by the river, when my Pundit Maharaj [guru] told me. I knew then.” Gangaram is all wide-smiles and excessive claims. But as we sit down, Gangaram’s hut is flooded with loyalists.

There is a young woman who says he diagnosed and cured her Typhus fever; a little girl who claims he got rid of her cough; a young man whose lethal migraines were cured by the old man: “You see, didi,” he tells me, “Every pill I ever took, it made me either sleepy or angry. I couldn’t work. I couldn’t ride my bike. Dadu [Gangaram] used massages and the Gods’ wishes to heal my headaches. It took time, but no money, and I didn’t put any chemicals into my system.”

The young man’s resolve weakens my skepticism. Gangaram is surrounded by people who love him, and backed by a wife who confirms everything he says by repeating it from a corner. He is supernaturally comforting, and doesn’t charge fees.

When I came looking for bonesetters in Kanpur, I expected chimerical, fanciful folklore. The lanes of Banaras promise eccentric philosophers; in little homes in Kerala, people will speak of men that can stand on one toe. But the bonesetters of Kanpur are not fleeting myths or quirky anecdotes. They are parts of their communities.

“Have you ever thought of making this a business?” I ask Badkau, back in the pink room. “Foreigners love this stuff.” I tell him about essential oils in shops in Paris, and the glamorous, commercial version of Indian tradition that is being appropriated all over the world.

He stares at me blankly. “My legs go from my home to the masjid to the bazaar,” he says. “I am not going anywhere.” Outside the clinic, there are 40 people waiting. A first round of tea has started going around.