The last female tile carver in a rapidly changing city.

“I don’t really care for the game,” says Ho Sau-Mei as she chisels a Chinese character onto a mahjong tile. She places the new piece in a row of 20 identically carved tiles. “Who has time to play mahjong?”

Known locally as ‘Sister Mei,’ Ho is the only female mahjong tile carver left in Hong Kong. She has been carving mahjong tiles for more than 40 years, and is one of the last mahjong sifus, or masters, left in the city. With no one new joining the trade, it looks like the craft may die with her generation.

When I first meet Ho, she is hunched over a tray full of freshly carved mahjong tiles. It’s 84 degrees Fahrenheit outside, one of the hottest days of the year so far. Ho, a tanned, a frail-looking woman of about five feet tall, doesn’t look strong enough to use a meat cleaver. But the sight of her wielding a carving tool proves otherwise.

It is so rare to see a specialized mahjong tile shop in Hong Kong that passers-by will slow down or do a double take when they see the small, colorful shop. Some stop to strike up a conversation with Ho.

Even as we talk, people slow down for a few seconds to sneak a peek inside. Ho is lively, friendly, and often stops work to briefly to talk to curious passers-by, both young and old. Many have never seen mahjong tiles being carved by hand.

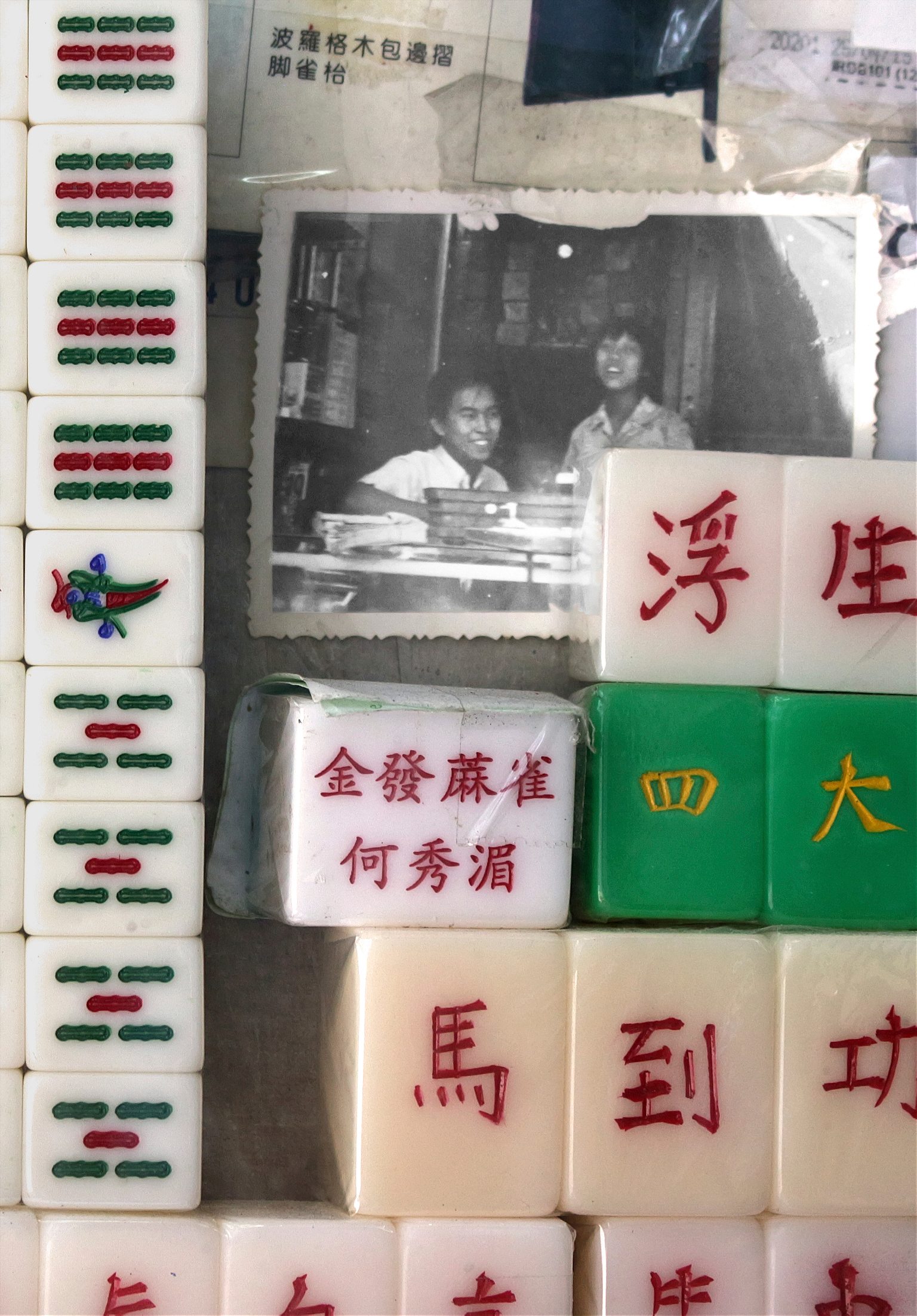

Her shop, Kam Fat Mahjong, is a lau tai dai po—literally, a shop beneath a staircase. The room is barely two meters wide, and you can just about fit three people behind the counter. A grimy glass case reaches to the ceiling and contains sets of colorful mahjong tiles stacked on top of each other.

The shop is lit by fluorescent ceiling lights and the faint red glow of a shrine at the far end. For her work, she relies mainly on the sunlight streaming through the front window. When it’s overcast outside, she uses a small wooden box lamp.

From 10 am until 2:30 pm, Ho works sandwiched between a glass case full of plastic mahjong tiles and the flight of stairs above her head, which leads up to three floors of apartments.

The walls of her shop are covered with fliers, newspaper clippings or photographs. One photo catches my attention: it’s black and white and nestled among the colorful tiles at the very front of the shop. The photo features two people, a man in his 30s and a teenage girl. They’re standing behind a glass shop counter identical to the one Ho is working on.

“That’s the sifu who taught me,” says Ho, pointing to the man in the photo. Next to him is a 13-year-old Ho. “My father invited him over from Guangdong. He taught me how to carve mahjong tiles at the same spot we’re standing in right now.”

Ho was five years old when she and her family arrived in Hong Kong from Guangdong province in Mainland China in 1962. After settling in Hung Hom district in the southeastern part of the Kowloon Peninsula, her parents opened the mahjong tile business in 1965.

Five years later, Ho started learning how to carve mahjong tiles. “I was the only of my father’s five children who wanted to do this kind of work,” she says. “My brothers and sisters wanted to do other things, so I ended up looking after the business.”

The game is an important past of Chinese culture, Ho says. But more importantly for Ho, mahjong is about family. “Sometimes when I have a day off on Sundays I try to play a game with my brothers and sisters,” she says. “Mahjong brings people together.”

Before Ho starts any work on a new mahjong set, she buys a set of blank plastic tiles, which are normally made from Bakelite. She then takes out five different types of chisels. There are tools for carving straight lines, one for carving concentric circles, and others are used for engraving Chinese characters and pictures onto the tiles. Ho makes all her tools, as they’re hard to find.

Finally, she paints the symbols and characters she has carved on the tiles using red, green and blue paint. She then applies some talc and cleans off any excess paint. Making a full set of 144 tiles can take up to one week, and will set you back around HK$1,700 (about $200 USD.)

Despite the availability of cheaper, machine-carved mahjong sets, sold for around $50, Ho still gets requests to longer-lasting, hand-carved sets. “I get all kinds of customers: hotels, banquet halls, even tourists come here to buy a set of tiles.”

Hung Hom is not an obvious tourist hotspot in Hong Kong. It is a largely residential area with newly-completed modern apartment blocks mixed in with Hong Kong-style tong laus, tenement buildings that were erected in the 1960s.

The only big landmark in Hung Hom is the Kwun Yam Temple, which was built in the 1870s and survived Japanese shelling during World War Two. From the outside, it seems like an unremarkable place. But not for Ho.

“I grew up here and I have a lot of childhood memories of this place,” Ho says as she looks around the confines of her shop. “That’s why I haven’t left.”

Hung Hom has changed a lot since Ho started working in the 1970s. Back then, this was an industrial area near the Whampoa dockyards. Fast forward 40 years, and the docks have been replaced by a private housing estate called Whampoa Garden.

Like many parts of Hong Kong, the area has seen its fair share of urban renewal, with the city’s signature bamboo scaffolding springing up along the walls of many buildings in the neighborhood.

Ho seems unfazed by the changes in the area she grew up in. “Of course there’s going to be change,” she says. “I don’t really have any strong feelings about it. Society is always changing. If you can’t accept change, then it’s you that has a problem.”

No one new has joined the trade in the last 30 to 40 years

The way people play mahjong in Hong Kong has changed, too. In 1956, the Hong Kong government issued the first mahjong parlor licenses: 144 of them, the same number of tiles in a game. Now, there are now fewer than 70 licensed mahjong parlors left in the city, and the game is often associated with gambling. While there is talk that mahjong itself is dying, Ho is quick to dismiss it.

“No way,” she exclaims. “Mahjong is still a popular game, it’s just the way people choose to play the game has changed.” Some people play it on their phones and computers, others prefer to have an electronic mahjong tables so you don’t have to shuffle the tiles yourself, she says.

There are no official figures, but Ho says she knows of only four tile carvers left in the city. In the 1960s and 1970s, she remembers that there were 20 or so mahjong tile masters.

“A lot of mahjong sifus have retired or found other work. Most of them are now in their 70s. I’m 60 years old now, and the person who taught me is now in his 80s,” she says. “No one new has joined the trade in the last 30 to 40 years.”

Renewed interest in the craft might change that. Ho and her peers have become local celebrities. In 2014, the Hong Kong government listed mahjong tile carving as part of the city’s ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage,’ alongside Chinese medicine, kung fu, and Cantonese opera.

“I get a lot of people visiting my shop and asking me to start teaching classes. I tell them ‘no way’, if you’re interested in it as a hobby it’s fine, but you can’t make a living from doing this as a full-time job.”

Living in Hong Kong is tough. HK$10,000 ($1,280) per month isn’t enough to make a living in in this city, she says. “And I barely make HK$10,000 a year doing this kind of work.”

Ho says money wasn’t a problem for her, as her husband and grown-up children all work. “Rent isn’t a problem because my dad brought this shop a long time ago. Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to continue running this shop.”

Although she is eager to keep working, Ho knows that she has had to take it easy now that she’s in her 60s. She doesn’t work as many hours as she used to. “My health isn’t too good these days; my eyesight isn’t as good as it used to be now so I only work in the mornings.”

Ho picks up a new plastic tile and starts engraving the Chinese character ‘west’ onto it. “I will retire when I don’t have any strength. Right now I’m working every day. As long as my arms are still strong, then I will keep on working.”