The High Holy Days, apocalyptic portents, and civil unrest: just another trip to the Holy Land.

I’m in line to pass through the metal detector at the non-Muslim entrance to the Temple Mount, Dome of the Rock, and Al-Aqsa Mosque when I hear multiple explosions. I don’t see any smoke.

A Christian tour group is ahead of me. “Palestinian teenagers setting off fireworks to scare the Israeli soldiers,” the tour guide explains. “Nothing to worry about.” He turns away from his group and gulps. I watch him study an Israeli soldier for an emotional cue, but the soldiers’ ears are glued to walkie-talkies, their eyes unreadable behind their sunglasses. The guide fights the urge to fidget and loses. His group of six stands erect and silent, like me.

I’m in Israel visiting an American friend and to attend a ten-day meditation retreat on a kibbutz up north. This is month seventeen of a twelve-month trip around the world. My savings had nearly evaporated and I’ve been buttressing its fumes on a beach in Thailand, teaching meditation and selling stainless-steel water bottles. But my increasingly serious exploration into Buddhism was hindered by a persistent concern: that I’d turned my back on Judaism too soon. Maybe it had more to offer spiritually than I had thought, in addition to community, culture, and tradition.

I had expected to spend a week in Jerusalem to tour holy sites; the Christian evangelicals expecting the apocalypse I hadn’t anticipated. The High Holy Days—the Jewish holidays of Rosh Hashana, Yom Kippur, and the days that fall between them—were coinciding with astrological events that some evangelicals saw as portents of doom. And I was there just in time to watch it unfold.

Twenty minutes later, I pass through the metal detector and soldiers lining the wooden walkway perched next to the Western Wall, the second-holiest site on Earth for Jews. The Orthodox Jews nod and bow to the Wall, cry and caress it, prayer books in hand. It feels serious, stern, rigid; believers trying to pierce the Wall with prayers to reach the Foundation Stone, site of the First and Second Temples. The Wall is still a barrier to this holy place, no matter how sacrosanct it’s become in its own right.

When I reach the Temple Mount I’m surprised to hear birds singing in the olive trees. It’s nearly empty. The peace is worlds removed from the firecrackers, prayers, and crowds at the Wall, the intensity of worshipers and vigilant soldiers. I fall into pace with a Jewish tour group.

“Muslims are certain Mohammed’s Night Flight to ‘the furthest mosque’ was on this spot, although Jerusalem isn’t mentioned once in the Koran!” The paunch, middle-aged, Jewish American smiles conspiratorially at his audience, pausing until they shake their yarmulkes in righteous indignation. When they raise their heads, their eyes are transformed by purpose. Being on the right side of God and history creeps up their spines like a drug.

I separate. Israeli soldiers carrying two unconscious Arab teenagers burst through an iron gate. The teenagers look heat stroked, maybe worse, but no one gives the situation, or the shouting behind the gate, a second glance.

Why’d the guy at the metal detector take my Bible?

I fall into step with a young guy from the Christian tour group from the security line.

“So where are you from?” I ask.

“Hey!” He extends his hand like we’re old pals. “Zechariah. Irvine, California! But God doesn’t care where we’re from.” He winks at me.

“Cool.”

“Do you know what the Birthright trip is?”

“Yes.”

“I’m on a Birthright trip, but for Christians. God has plans for me this moon amongst the Jews.”

“Awesome.”

We walk away from the shouting mob, invisible behind the iron gate.

“Why’d the guy at the metal detector take my Bible?”

“Only Muslims are allowed to pray on the Temple Mount. A Bible or any non-Muslim religious artifact is contraband.”

“Seriously?”

“Security will escort out a Jew or Christian suspected of praying,” I say, shielding my eyes from the gold Dome of the Rock, blinding in the morning sun. Righteous indignation at human stupidity courses through me. I wonder what the difference is between righteousness and the tour group’s.

“Wow. Mecca,” Zechariah says.

“Mecca is in Saudi Arabia.”

“I thought this was Mecca. The holiest place in the world for Muslims.”

“Mecca is the holiest place in the world for Muslims, but it’s in Saudi Arabia. Medina is the second holiest, also in Saudi. This is the third holiest.”

I study the blue arabesque tiles on the outside of the Dome. The past few days, I’ve seen the Flower of Life pattern inlaid in arches of Crusader castles near Caesarea, in slideshows about Mt. Masada, on Kabbalist literature in Tel Aviv, even on the cover of an Italian roommate’s book about Da Vinci. That I’d frequently seen a universal symbol representing the interconnectedness of life in the land of fragmentation I’d taken as encouragement. The designs are vivid and incredible but I don’t see the Flower.

“So what is this place?”

“It’s the holiest site on Earth for Jews. Inside there’s a stone called the Foundation Stone. It’s what God created the world from, and Adam. This was the sight of the Holy of Holies in the First and Second Temples. The Arc of the Covenant was kept here before it vanished. It’s where Jacob dreamt of his ladder, where Abraham was about to sacrifice Isaac, and where Mohammed ascended into heaven. All supposedly. Jerusalem is a mélange of myth and history.” I pause.

“It’s also where L. Ron Hubbard wrote Dianetics.”

He squints at the Dome again. “Are you Muslim?”

“I grew up Jewish. Now I’m an out-of-the-closet Buddhist.”

“The Lord has brought us together. We should pray.”

“We can’t. We’ll get kicked out.”

We silently circle the Dome. I ask three Muslim women in hijabs lounging in the shade against the Dome for permission to take their photo. They wag their fingers no.

A group of a dozen or so Jews in civilian clothing enter The Mount. They put their hands on their hips and look around. I get an undercover cop vibe. Their leader gesticulates to the Dome and raises his voice. The group nods fiercely, says something I can’t make out in a call-and-response. Some extremist Jewish groups were actively trying to reclaim The Mount. Skirmishes—between Jews and Israeli soldiers, Muslims and Israeli soldiers, Jews and Muslims—and arrests for swaying or “murmmering” have been relatively common since Israel regained control of the Temple Mount in 1967. The Muslim women in the shade get up and leave. I lead Zechariah away.

“Before I found the Lord I was a drug addict and a womanizer. One night I was at my friend’s house, smoking bongs. I didn’t feel good about myself. I had low confidence and slept with a lot of women. I got in the car to drive home but was very high. I asked Lord to guide me. And he did, Michael. He did. It was a miracle. I haven’t slept around or taken drugs since.”

Zechariah’s eyes were kind and sparkly. He was twenty-two, 5’5”, pudgy, and bearded. His feet were fat and hobbit-esque, an uncooked bagel squishing out of Tevas.

“I was addicted to marijuana,” he says.

“You can’t be addicted to cannabis.”

“I slept with a lot of women to feel good about myself.”

“Nice to meet you, Zechariah. I’m heading—over there.” I motion to elderly Muslim men sitting on folding chairs in the shade of an olive tree. I extend my hand.

“Can we pray together?”

“There’s a prayer detector on top of the Dome that measures the electromagnetism of infidels’ hearts and pineal glands.”

“I won’t be obvious.”

“Just joking.”

He slaps me on the arm, laughs, and bows his head.

“Lift your head.”

He looks to the sky.

“Lower your head.”

“Lord, I want to say thank you for giving me the chance to meet Michael today. I want to ask you to bless him and keep him. He’s a man of extraordinary gifts and talents to offer this world, and I ask you to guide him on the righteous path so he can fulfill your plan.”

No one had spoken this kindly or thoughtfully about me in a while. As Zechariah prays, I am bewitched, if subtly, by the appeal of surrendering cynicism and doubt and letting someone else drive. It wouldn’t involve years of meditation, philosophy, and discipline, but immediate abnegation of autonomy. I get goosebumps at the possibility of opening my heart and surrendering, even if I don’t know exactly what I’d be surrendering to.

I stroll the olive grove. Olive trees can live for thousands of years. Some of these trees may have witnessed Mohammad’s flight, or Titus’ destruction of the Second Temple in 70 A.D.

I caress an olive. I remind myself to pray more. Especially for others.

One of the old Muslim men springs from his chair and rushes toward me.

“You! Go now!”

“I won’t touch the olives!”

“GO NOW!” He motions to the exit like his sweater is on fire.

“Why? Mount open for two more hours.” I jab the top of my wrist but stare at the ground, nervous that he saw us praying.

“Jew Muslim fight!” He runs off to warn others.

I hear chants in Arabic not far off. Voices speaking Hebrew are raised in response.

I exit. I find myself on the Via Dolorosa. On my phone, I read about Jesus’ Passion and the stations for Christian pilgrims: where Jesus had his brow wiped, where Jesus was condemned by Pilate, where the cross Jesus dragged was attached. I feel a thought-negating awe at walking through history, but it feels simultaneously silly. Why were we so obsessed with real estate?

I buy olives near the Damascus Gate. I sit next to Muslim twenty-somethings, smoking silently and scrolling their phones. I watch old women in burkas sell figs.

I arrive back at Abraham Hostel exhausted. I’d visited the Western Wall, the Dome of the Rock, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre within a few hours. It was a lot to take in.

I found the Flower of Life carved directly above the entrance to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, where Jesus is entombed. It was also engraved on a floor tile upstairs, near the small chapel where he was crucified. The Crusader’s fondness for the Flower was curious: a symbol representing the inter-connectedness of life seemed anathema to the murderous campaigns of ethnocentric fanatics.

I enter the dorm and see an old Chinese man in a wife-beater and pants he’s too skinny for pacing around. I’d seen him around the hostel common areas. He was politely tolerated by the staff, like he was a puppy they enjoyed petting but not feeding. I felt sorry for his roommates. Israel is expensive, so I’m sleeping in a dorm for the first time in fourteen years.

“Hello! Where you from?” he asks.

“New York.”

“Ew Yor Shitty!” He smiles wide, revealing toothless gums. He claps his hands three times and laughs like he’s pulled a quarter from my ear. “You know Queens!”

“Yes, sir.”

“I lived, worked, in Flushing, Queens, many years ago. Flushing, Queens. Many years ago, so long ago. I am old. Flushing, Queens…” He trails off but catches himself. “Now missionary live Taiwan! Taiwan! Taiwan!”

“SHUT UP SHUT UP!” An old Chinese woman in Karl Lagerfeld sunglasses and a white tennis skirt yells at him from her top bunk.

“He from Ew Yor! Ew Yor Shitty!” He closes his eyes and mumbles inaudibly as the woman on the top bunk harangues him in staccato Mandarin. “Queens? You say Queens?”

“No, sir.”

He claps his hands three times. “The Lord, The Lord, The Lord—” he falls to his knees, lifts his skinny, flabby arms to the sky and closes his eyes “—and the moon bring us together. The Lord always—”

“What do you mean ‘the moon?’”

He moans a Chinese, Hebrew, and English prayer in animalistic howls. I flick the hot water switch for the shower.

From his knees, he grabs the bottom of my T-shirt and looks at me. An unfathomable despair at his incompetence to do the one thing he wants to do with his remaining years—help lost souls find the Lord—shines from the depths of his cataract-marred eyes. I squeeze his shoulder. I’m overwhelmed by pity and empathy that his yearning to be of service actually hinders any serviceable utility. He brings his hands together in prayer and raises them over his head.

The water isn’t hot yet but I risk it and jump in. When I exit in a towel their eyes are closed and they’re swaying, hands together, singing:

“Miiiiiiichael Green, Miiiiiiiiiichael Green, the Lord loves Miiiiiiiiiiichael Green, may the Lord forever keep Miiiiiiiiiiiichael Green, Miiiiiiiiiichael Green, the Lord loves Miiiiiiiiichael…”

“How do you know my name?”

Most of Jerusalem is shut for Rosh Hashanah, so I eat the hostel’s communal buffet. I sit next to a Canadian in an orange polo tucked into his jeans. He is clean shaven, probably forty, with a square, almost military haircut. His ear is being chewed off by my Taiwanese roommate until I tap the Canadian’s shoulder and ask if he’d like to get in line with me for seconds.

“He’s nice,” I say. “But sprung the book on me within a minute.”

“I’m a person of faith so I don’t mind that. I just can’t understand him.”

I gulp. We scoop potato salad onto our red plastic plates.

“I didn’t mean to offend you.”

“Oh, none taken.”

“I don’t know much about the messiah, the New Testament, all that. I’ve been in Asia all year, and before that New York. I don’t meet many religious Christians. Jerusalem’s been a big surprise.”

“Would you like to learn about the messiah?”

I shrug. “Sure.”

I get it now. They want the apocalypse

I buy a pint of Shapiro Pale Ale from the bar and we sit. Todd explains that we messed it up the first time so now we’re waiting for redemption. He continues for an hour. I realize I’ve tuned out when he says: “To be honest, I’m in Jerusalem now for boots on the ground. In case God needs me this moon.”

“What do you mean ‘this moon?”’

“Four blood moons have occurred in a little over a year. It’s happened only a few times in history. All have coincided with Jewish Holidays and major events for the Jewish people, like the ’67 war, Independence in ’48. A biblical prophecy says that the messiah will come during the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, in two weeks.” He looks at me apologetically, like I think he’s weird, but I’m impressed by his earnestness and dedication, that he’s flown across the world, and left his wife and kids at home, on spec.

“Tell me about this Melchizedek fellow,” I say. When Todd began his messiah story, he said that when Abraham arrived in Jerusalem there was already a High Priest here named Melchizedek. I’d begun Drunvalo Melchizedek’s book Ancient Secrets of the Flower of Life, and thought that maybe the Jerusalem priest was Drunvalo’s namesake.

A bearded, girthy, 6’4” American guy in cargo shorts and leather vest approaches. Todd introduces us.

“New York! Dude, I had a prophetic dream about New York,” the large man tells me. “I’m not one of those guys that says he has prophetic dreams or anything, but the Mets were playing in game six of the playoffs and there’s going to be a big event. I’m no prophet, but God has plans for us and they’re not always pretty, no sir. I looked it up and guess what, folks? The Mets are in first place.”

Todd and the man smile and shake their heads. I shake my head at their apophenia and the Mets’ infamous futility.

“All I’m sayin’ is that you don’t want to be in New York then. Nice to meet you, bud.”

The man slaps me on the shoulder and leaves with Todd. I visit Haaretz, the Israeli news site: Clashes Between Palestinians, Police Rock Temple Mount on Eve of Rosh Hashanah.

The next morning at the coffee machine I’m in line behind two American women. The elderly one says, “Tryin’ times!”

“Mmmmm hmmmm,” the younger woman says. “Revelation 6:12: I looked when He opened the sixth seal, and behold, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became like blood.”

“Comin’ to a theater near you, hon.”

“Front row, ma’am.”

“Devil got ‘em all!” The older woman says. She presses ‘cappuccino.’

I get it now. They want the apocalypse. I’d thought it was something to guard against, like getting audited, or a shibboleth of hooey swallowed alongside community, culture, and tradition, but the apocalypse is the evangelical true spring. I press ‘americano.’

The only empty swivel stool at the communal table is next to the younger girl. I sit reluctantly and resume reading Jerusalem: A Biography by Simon Sebag Montefiore, thus far the perfect guide book. I feel her staring at me and giggling. I lower the book. She is cackling, feeding on my infidelity (I think) like a wolf. I smile sympathetically, nod, and lift up the book again. She huffs off.

A Palestinian friend I met in Thailand connected me with her Palestinian friend, Nazrim, who picks me up outside my hostel. She chain-smokes and points out former Palestinian villages wiped out to make way for the “apartheid wall,” and the sprawling Jewish settlements on stolen land. The wall is massive. When completed, it will stretch about more than 400 miles. We drive past olive groves on otherwise barren hills. An Israeli soldier lazily waves us through the checkpoint into the West Bank.

“That’s it?” I ask.

“We’re leaving Israel. Different coming back.”

We park at an organic farm in Beit Jala, a few miles from Bethlehem. We drink Palestinian beer and eat fresh figs with Ghassan Zaqtan, the owner, a Palestinian poet and novelist. I’ve never eaten fresh figs before, only dried ones, and eat the entire basket as Ghassan gets back to work.

Nazrim gives me a copy of This Week in Palestine magazine. It features hotels, bars, art galleries, and restaurants around Hebron, Jericho, Ramallah, and other places.

“All we hear about in the West is war.”

“You’re brainwashed.”

“Probably.”

“Go to Jericho. The electrons in the air make you clearer.”

“I wonder if it’s electrons that give different places different energies.”

“Probably,” Nazrim says, finishing her beer.

Ghassan brings out grape leaves and stuffed zucchini. It’s the best meal I’ve had in the Middle East.

“So what do you see happening?” I ask. “In Palestine.”

“It’s a European problem, not a Palestinian one.”

“What do you mean?”

“The Jews. They have to go back to Europe or wherever they came from.”

“That’s the solution?”

“Not saying it’s the best, but it’s what I want.” She closes her eyes. “I grew up on a Kibbutz in Israel. I used to believe in peace. I don’t anymore.”

“So your version of peace doesn’t include Israel as a country?”

She takes a drag. “Yes.”

I suggest a drink at the American Colony Hotel, respected by Israelis and Palestinians as neutral territory. Nazrim is excited, but represses her enthusiasm as soon as it surfaces.

“I can’t.”

“Why?”

“I’m a Marxist.”

“So what? Everyone goes through a Marxist phase.”

“If I’m seen in there I’m dead.”

The next morning I go to the “Arab” bus station near the Damascus Gate and take a bus to Bethlehem. I visit the Church of the Nativity, see where Jesus was born, and eat msabbaha (a soupy hummus) at Afteem, a popular local restaurant. In Manger Square I study a large map charting the gradual, mostly illegal Israeli usurpation of the West Bank. The West Bank appears on the map as a full lake in 1946 and shrivels up nearly completely, barring a few puddles. It was more than I’d realized. Maybe I am brainwashed.

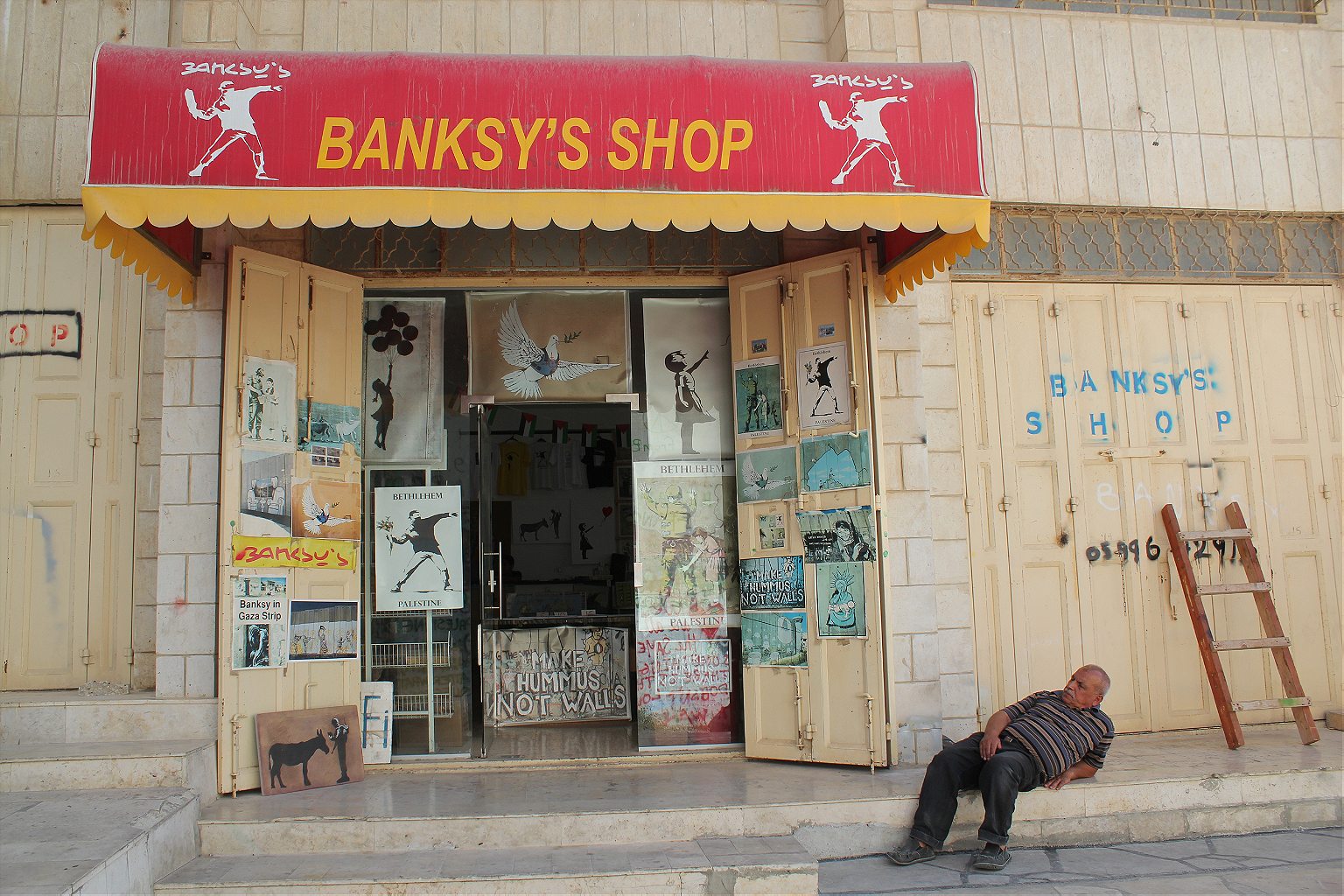

I take a taxi to the separation wall to see the Banksy tags. I read the personal stories of occupation plastered to the wall and admire the local art, which has subsumed the Banksy pieces over the years. I exchange pleasantries with three Palestinian men on plastic chairs, sipping tea from small glasses in front of the wall.

My taxi gets stuck in traffic on a wide Bethlehem highway. The A.C. is off, the windows are down. I hear chanting. It grows louder, closer, and angrier. Through the windshield, I see about a hundred Palestinian teenagers with rocks in their hands and towels around their faces. They’re pumping their fists in the air, smacking car hoods, snarling traffic. They’re marching en masse in the middle of the street toward us.

I turn white. I’m ill and helpless with adrenaline as the swarm approaches. I want to watch but I’m not breathing. The driver smiles at me through the rearview.

“No care for you. Only Israel.”

The mob marches past us to the separation wall.

On the bus back to Jerusalem, I’m the only passenger that doesn’t have to get off and proceed individually through the checkpoint.

Back at Abraham Hostel, I down a Shapiro Pale Ale in a single gulp. Articles about the day’s clashes in Bethlehem (and Jerusalem, Hebron, and other places) have appeared on The Guardian and RT.

I trace a direct route on my map app and walk to the American Colony for a drink. I unknowingly walk through Mea Shearim, one of Jerusalem’s most orthodox neighborhoods. I’m given dismissive looks by the adults as I pass the Please Dress Modestly signs.

In the morning, I sit in a cafe on Jaffa St. I feel lost, sad, and aimless. Looking for connectedness I’ve found only division. I put my chin in my palms and stare at the table.

I see, suffering from classic Jerusalem Syndrome, what God wants. God wants us to stop taking Him/ Her so seriously. He/ She wants us to say that we’re going to live in peace and harmony and embrace one another as brothers and sisters no matter who we are or what we believe in because we’re all human with divine nature that permeates and penetrates every inch of us and this Earth, not just one sect or one site in one city.

The spell of this city was and has always been truth spliced up and canonized by warlords, kings, and hierophants. The occasional truth-teller gets appropriated by lies and Father Time until loving-kindness is warped into divisive dogma. Possession of the real estate where IT happened becomes as important as faith, and God comes to exist in finite cracks and not in the plenum, the true Foundation Stone, the Flower of Life.

Are you saying no to God, Michael?

“No way.”

I raise my chin from my palms. Zechariah and three friends stand before me.

“God sure has his ways of bringing us together! I was just telling my friends about you and here you are!” Zechariah brings his palms to prayer.

“At your service.”

“God wants you to have this book, Michael.”

He hands me Four Blood Moons: Something is About to Change, by John Hagee.

“Thank you, Zechariah, but—“

“Are you saying no to God, Michael?” Zechariah and his friends laugh.

“The Messiah is coming for Tabernacles/Sukkot! We want you to be saved.”

I take the book. “Please tell God thank you.”

“You can thank him yourself! Come to Bible study with us.” Zechariah instructs me how to take a tram, make five turns, ring a buzzer, and punch in a ten-digit pass code to reach the study room.

“See you there, Michael?”

I wedge Four Blood Moons between The Ancient Secrets of the Flower of Life, Jerusalem: A Biography, and a Ramana Maharishi paperback in my bag.

They walk off before I can answer.