Edinburgh’s Broughton Street has a famous chip shop. This is the other one.

I didn’t want to live on Broughton Street.

It wasn’t that I disliked the area. Then—in the early 2000s—and now, Broughton Street was a prime spot, a sloping downhill street lined with restaurants, cafes, and odd shops, a short skip from Edinburgh’s East End and the city center. The hub of a parish that once contained dungeons where those suspected of witchcraft were held to await execution, these days it combines a trace of its former bohemian cred with the genteel air of Edinburgh’s New Town. It has both tattoo shops and storied butchers, pioneering restaurants and old-man pubs, at least one store selling nothing but tweed jackets and tweed furniture, and a handful of legendary LGBT bars.

But I was a second-year student in Edinburgh University’s Humanities faculty, housed in a collection of squat ‘60s-era buildings on the south side of the city. Most of my peers lived mere minutes away from our lecture theaters in high-ceilinged Victorian tenement flats in Marchmont or along South Clerk Street. I had my heart set on rolling out of bed at 8:40 a.m. for a 9 a.m. class. Broughton Street was down the hill and across the Bridges—in Edinburgh terms, a world away from campus.

But my roommate, a Philosophy major and Edinburgh native, wanted to live in New Town (ish) and he sweetened the deal by finding a cheap, spacious (and damp) basement flat and offering me the largest room.

In addition to its fine stores and restaurants, Broughton Street is bookended by two chip shops—chippies—those essential purveyors of British post-drinking fare from fish and chips to deep-fried pizza. Caffé Piccante was, and remains, at the top of Broughton Street next to a busy intersection, and gets all the headlines: it’s a favorite of visiting Edinburgh festival celebrities and is also known as the Disco Chippie because it sometimes holds DJ sets.

Rapido Cafe was, and remains, a couple of hundred yards down the hill, with a bright orange storefront, smaller than Piccante, but crucially, only 37 seconds from our front door. By sheer proximity, it became our local, and how I acquired a taste for Scottish chippy food.

[Read: Scotland’s other national drink is a perfect hangover cure. Maybe]

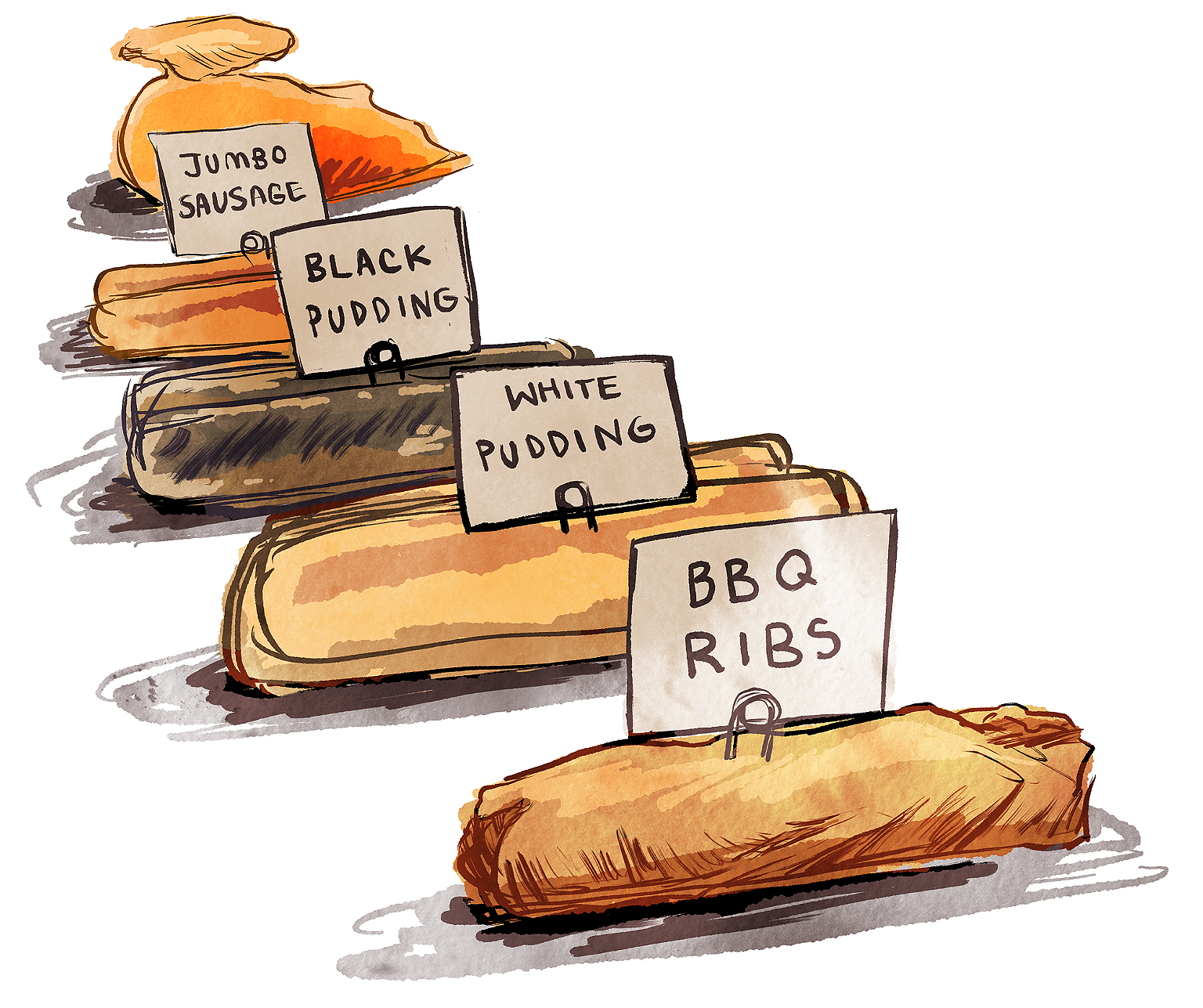

Rapido is a tiny place—two metal tables and chairs—with a long menu and deep-fried wares sweating on display under harsh light. With a nod to its Italian roots, the options include a large range of pastas, calzones, and pizzas (including some ‘gourmet’ pizzas such as prawns with Tabasco) as well as the usual chippy suspects: deep-fried haggis, haggis pizza, baked potatoes, fish and chips, deep-fried blood sausage, white sausage, and other blood and fat and gristle combos. (They’d probably deep-fry a Mars Bar for you, but I have never seen anyone order one.) They also have decent-looking vegetarian options, though I have never ordered any.

My usual order was another Scottish standby: the smoked sausage supper. This sausage is a thick, German-style hot-dog, generally pork, not dissimilar to Knockwurst or a supersized Frankfurter, but smoked and much saltier. It became popular, possibly, thanks to Matteson’s, an England-based meat manufacturer founded by a German immigrant that started producing the smoked sausage in the 1970s. But no one seems to know for sure, or why this chip shop standard is more common in Scotland than England. The “supper” means it comes with thick chips, and just like all over the city, the server will ask if you want “salt and sauce”—the latter a special Edinburgh chippy sauce. Each place their own secret recipe, but it’s usually some proportion of Gold Star brown sauce mixed with vinegar, and it’s perfect.

Sometimes I would mix it up by ordering their spring rolls, which looked more like burritos, with just a hint of soy sauce. With chips, this supper resembled a rough sea of glistening beige, in a matching Styrofoam case.

[Read: Edinburgh, explained in 10 dishes]

In our 10 months in that basement flat, Rapido became our place for for post-study quick dinner, post-TV-all-day dinners, a post-pub site of late-night summits and post-mortems, many ill-advised final bottles of Peroni, and packs of cigarettes. (They also sold aspirin.) In the era before Deliveroo and JustEat, like PostMates and Seamless, brought our every whim and craving to our front doors, our late-night stop across the street was an endless treasure. They knew our names. They forgave us scenes caused by dramatic, drunken friends and let it slide when we didn’t have quite the right amount of change.

In the way they say friends are your chosen family, Edinburgh was the first place I chose to live. I arrived at the age of 17, and left seven years later, reluctantly and in the dead of night along the A-roads towards the M6 motorway and London. Edinburgh has been a hard city to live up to ever since. Rapido is not why I loved it, but it’s one of many fond food memories that, added up, made Edinburgh feel like home, and made it so hard to leave. If only it weren’t so darn cold.