How does one become a successful chef and restaurateur? If there is a standard path, Andy Ricker sure as hell didn’t take it.

An iconic advocate of Northern Thai cuisine in the United States best known for his Pok Pok Restaurants, Andy Ricker is one of the guiding forces behind the League of Travelers. The award-winning chef, restaurateur, and bestselling author spoke to R&K’s Charly Wilder from his home in Chiang Mai.

How does one become a successful chef and restaurateur? If there is a standard path, Andy Ricker sure as hell didn’t take it. His winding, peripatetic journey from dishwashing ski bum to two-time James Beard Award winner reads like a modern-day picaresque. Moving across the globe often on little more than a whim, he worked as a pumpkin picker, a house painter, a fisherman, a busboy, a maintenance man, a gigging musician, a contractor, and a ships’s cook, eventually opening the original Pok Pok out of a converted residential house in Portland.

And what did he do once he had finally built his small but mighty, Michelin-starred restaurant empire? He shut the whole thing down in the first weeks of Covid and relocated full-time to Northern Thailand. A key figure in the League of Travelers, Andy spoke to us between trips from his home in Chiang Mai about his jagged journey and where he’s at now.

Roads & Kingdoms: Okay let’s take it from the beginning. How did you wind up a chef?

Andy Ricker: It started in Vermont. My family lived in a place called Jeffersonville, which was at the base of the mountain of Smugglers’ Notch ski area, on the other side from where Stowe is. My choices were to go work at the gas station, go work at the sawmill, or go work at the mountain. And when you worked at the mountain in the wintertime, you had two choices. You could stuff butts, which is working the chairlift, or you could go work in food service. My first job was working in a fondue restaurant as a dishwasher, which… picture that. It’s a bit of a nightmare, but it didn’t discourage me. I started that when I was 16, and that was it. I just never left the kitchen.

Roads & Kingdoms: So then what got you out of the States? How did you end up in Southeast Asia?

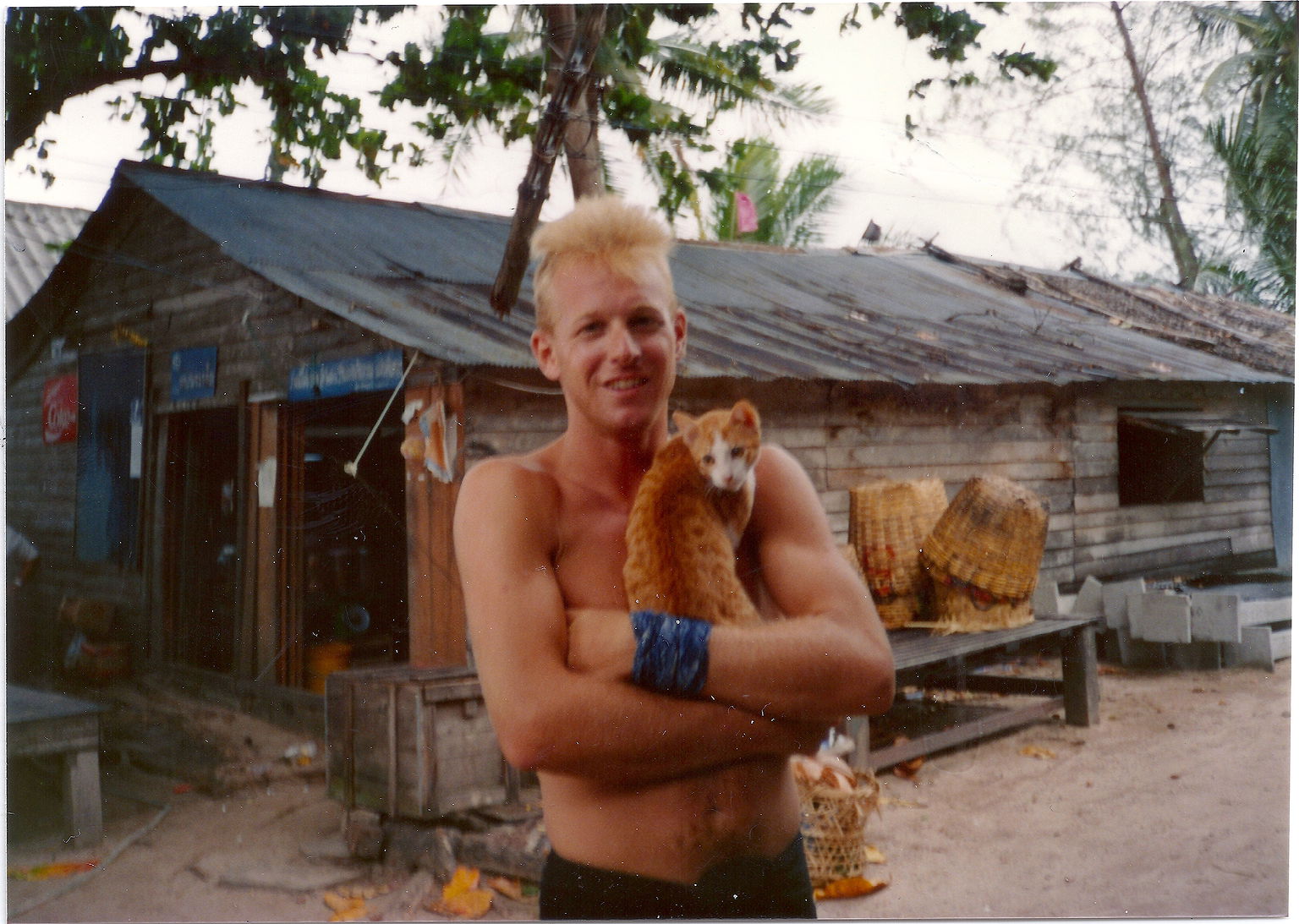

Andy Ricker: I left Vermont a couple days after high school graduation, and I headed west. I was in Vail, Colorado for about three and a half years working as a cook and skiing, being a ski bum. Then the word on the street was, you’ve got to go to Australia. So I threw whatever possessions I had into a backpack, and I had about enough money to last for about three months, staying in hostels and camping, but I ended up staying away for almost four years. I lived in New Zealand. I lived in Australia. And then I got hooked on rock climbing. And what I kept on hearing was, you’ve got to go to Thailand. Thailand’s where it’s at. So I went to Thailand (in 1987) and stayed for about six months, that was my first trip. Then I got Dengue fever at the end of it on an island down south. I’ve got photographs of myself—I was really, really skinny.

Roads & Kingdoms: Were you working in restaurants when you were traveling around?

Andy Ricker: I was working wherever I could work. I did everything from painting sheep-shearing stations to packing kiwi fruit to working in pumpkin fields. I worked at a mountaineering shop. After I got Dengue fever, I went to England to see my friends who I’d met on the road. In England, I was a house painter, I was a DJ, I worked in restaurants as a cook. I just did whatever I could to keep going, because I had no money. So if I wanted to stay out, I had to do it myself.

Roads & Kingdoms: So then you eventually decided to come back to the States?

Andy Ricker: At the end of 1989, I came back to the States and then I kept on moving. I was in Vail again, working in an athletic shoe store and cooking and delivering papers and whatever I could to keep going. And then I went to Portland, and I went to Alaska to work on a fishing boat. I worked in a cannery. I worked in a restaurant there. I went back to Colorado again and was working on an organic farm.

I didn’t go to Thailand for two weeks and come back and open a Thai restaurant. I went again and again for 13 years before I felt brave enough to open a chicken shack.

Roads & Kingdoms: What motivated you to move around so much? Were you just following opportunities or kind of embracing a wanderer’s life? How do you look at it?

Andy Ricker: Well, there was always a purpose. It was one thing to the next. I was a rock climber, so I would go where the rock climbing is, and that would influence where I was going. I didn’t go to Vail to work in restaurants—I went there to go skiing. I went traveling because I was curious. It was more like, where’s the next cool place to go? I also started fly-fishing in New Zealand, and that started being a thing that would move me. There were relationships that I would pursue, girlfriends…

Roads & Kingdoms: But at some point you wanted to stop moving for a bit?

Andy Ricker: When I returned to the United States, I was just kind of like, holy shit. I’ve been living out of a backpack for four years, and I hadn’t really had a chance to dig in and be part of a community. But it took me another year of blowing around until I finally landed in Portland. It was 1990, I think. And that ended up being 30 years. I don’t mean that I stayed there the entire time, but I had a home there.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did you end up opening your first restaurant?

Andy Ricker: Well, whenever I showed up somewhere and I needed to work, the first thing I would do is look for restaurant work, because that was what I was good at. And I had a good resume because while I traveled around the world, I had gone and staged at some pretty famous places, and I had chops. And so I ended up in Portland and I ended up getting a job at what was at the time, the best restaurant in the city called Zefiro. And I was there for a few years. Then I started playing in bands. And you’ve got to have some kind of living while you’re paying in bands, because playing in bands ain’t gonna pay the bills. So I shifted away from cooking to bartending, because that was even easier.

Mostly chefs are focused on the food and their staff, and that’s it. I knew what was underneath the sheet rock.

Roads & Kingdoms: Yeah, that’s what I always did.

Andy Ricker: I was the guy who was like, I’ll take the day shift. Nobody else wanted the day shift. It wasn’t as lucrative. But for me, it was great because I could play at nights. So I was in bands for 13 years, and then I shifted back to being a house painter, because being a house painter was the ultimate freedom. Now I work for myself. I’m not punching the clock for anybody, nobody’s making my schedule. It’s very lucrative. I was really good at it. I got trained in New Zealand and Australia and England, where it’s a real trade. And now I was a business owner, and I carried on with that for about nine years. But then I got sick and tired of that, and the only thing I knew to go back to was restaurants. By this time, I had zero interest in working for anybody else. And you talk to any cook at any level, anywhere. And what’s their goal? To open their own restaurant.

Roads & Kingdoms: And now that you had run a business, you had some idea about how to do that.

Andy Ricker: Right, and I had been traveling to Thailand every year. The whole time that I was painting houses, I was also returning to Thailand every year, starting in ‘92. And I was learning the food. I had gotten hooked on Thai food. I had been introduced to the local food here (in Chiang Mai). I had been cooking with people who were my mentors. I was doing dinner parties at my house. It was shades of the future to come, where everything’s a pop-up, I was just doing parties and inviting people over and feeding them.

Roads & Kingdoms: Were you charging?

Andy Ricker: No, I was making money as a house painter. I was rolling in it. I lived in Portland, Oregon. We had Nike, we had Intel. There were fucking millionaires just walking all over the place, buying their first mansions. I was making dough, and living costs were low back then. So if I spent 150 bucks and threw a party, who cared? It was great practice for me.

All the major food magazines were showing up to do profiles on chefs. Even Men’s Health, it was insane. There was so much attention on Portland.

Roads & Kingdoms: Were you still playing music? And what were your bands? Are we talking grunge?

Andy Ricker: That was the era, but all the bands that I was in were pretty wildly out of step with the times. The first band that I was in in Portland was called the Moxy Love Crux, it was a bike messenger band. After that, I was in a band called Vehicle, which was probably band-wise the love of my life. We were playing this melodic garage pop that was out of keeping with all the grunge stuff. But we played with all the grunge dudes. And then I was in a band called 44 Long, which was the one that probably had the most commercial success.

Roads & Kingdoms: What did you play?

Andy Ricker: Bass or guitar, depending on what was needed at the time. And sometimes I would play guitar in a band and then the bass player would quit and I’d play bass. And for 13 years or something, that was the most important thing in my life.

Roads & Kingdoms: Were you trying to make it?

Andy Ricker: Well, I never had any illusions that what we were doing was commercially viable, but there was always that kind of hope that you could become a touring band and record and be self-maintaining. And that never happened, but I also on the side was learning about this Thai stuff, that in the end, that won out big time.

Roads & Kingdoms: So how did Pok Pok happen?

Andy Ricker: What happened was I met this woman, and she was in New York City. This was 2003. I went to New York and I lived there briefly, and it was a fucking disaster. The relationship didn’t work out, but I was painting. I was dragging my little cart on the subway up to the Upper West side and painting brownstones, so I was making a ton of money again. And this idea of opening a restaurant had been percolating for years at this point. And I took stock of the situation in New York, and I was like, there’s no way I can open a restaurant in New York. It’s not possible. And back in Portland, I had this house. I bought a house with the largess from being a painter, because at that time, it was really, really cheap to buy a house. So I went home from New York after this disastrous but very edifying sojourn there, and I gutted my kitchen and I ripped the attic out, and I doubled the size of everything, made it really a great place, increased the value, pulled the money out of that, bought another house, flipped it, built this equity. And then I went looking for a space to open a restaurant. I didn’t even bother looking to rent anything.

Roads & Kingdoms: Smart.

Andy Ricker: I just went straight to what can I buy to make a restaurant in and live in? Because in Portland we have this thing where they have houses with commercial spaces in them, leftover from the ‘70s. And I found a place, and it was an old house, part of which had been built in the late 1890s. It had been scabbed onto in the teens and then again in the ‘30s. And it had a little sushi hut out front that had been built in the ‘80s and a little commercial kitchen in the basement that had also been built in the ‘80s, when code was super lax. And because it was grandfathered in, I could go ahead and open a restaurant there, which is what I did. And I lived there while I was building it.

I had maxed my credit cards out. I was basically just rolling and dodging predators.

Roads & Kingdoms: Was it immediately successful?

Andy Ricker: Well, first of all, I had to build it. That took probably eight or nine months of getting it prepared, just so I could open this little shack and sell roasted chicken. And initially, the first month or so, I was just trying to figure it out. My friends would come, and it was winter, and it was open in October and November in Portland. And by the spring, we had lines down the street. So it was scary, because I was taking all the money from that and pumping it back into the house to build out a proper restaurant. I had maxed my credit cards out. I was basically just rolling and dodging predators. And then I opened the proper restaurant again in the fucking dead of the winter. We were slow. We were not busy enough, and it was scary. And then we got chosen as “Restaurant of the Year” by the Oregonian, and that was it. It was off the races. We just never looked back and became wildly successful from there.

Roads & Kingdoms: And you opened quite a few locations, right?

Andy Ricker: Yes, as the years went by. Pok Pok was in operation for 15 years. We opened Pok Pok in 2005. Then Whiskey Soda Lounge in 2009. There were three years or so where it was just Pok Pok, and I was just ripping my hair out. And then we got to a place where we had to expand. I just ran out of space. So we opened across the street, and then we opened up the street, and we opened downtown, and then eventually New York, and then eventually LA and then expanded, contracted, expanded, contracted over the years.

The rents were low, so you could afford to do stuff that was not standard. You could open a place that was funky as hell, and Pok Pok was funky as hell.

Roads & Kingdoms: Why do you think Pok Pok was so successful?

Andy Ricker: I think that it was the right place at the right time with the right audience. There were a bunch of things that happened simultaneously. Number one: Portland saw this incredible boom in restaurants, and there was a lot of attention on that. I don’t know if you recall that, but Portland was the precursor to what happened in Brooklyn later. This was 2004, 2005. Portland was exploding, because we started the farm-to-table movement. Paper Magazine was showing up. Interview Magazine was showing up, all the major food magazines were showing up to do profiles on chefs. Even Men’s Health, it was insane. There was so much attention on Portland.

Number two: the rents were low, so you could afford to do stuff that was not standard. You could open a place that was funky as hell, and Pok Pok was funky as hell. You could sell the food relatively inexpensively, serve it on melamine plates. This was also something that wasn’t being done anywhere else, with oilcloth tablecloths in a non-conventional space. And you could make food outdoors, you could put a grill outside. The Health Department was kind of like, well, we don’t know what to do with this, but I guess it’s okay. And then we started making food that was really, really true to, not only the flavors, but how it was made in Thailand.

Roads & Kingdoms: This just didn’t exist at the time?

Andy Ricker: Thai food in America at the time was American-style Thai food. It was made in a certain way with a certain flavor profile. And what we were doing was just different, and I think it was exciting to people. And then finally, we were working with farmers, so the food was great. And it’s not because I was a great chef or anything, just because I was learning from people who said, you’ve got to use proper technique and you’ve got to use proper ingredients. Here’s how you do it. But also because I’m an American and I had a toe into Thai culture, it was easy for me to describe in the English language in a concise and understandable way what people were getting into. Instead of it saying, “green curry with chicken feet,” or “salt-and-pepper squid,” I was able to describe what it is: gaeng hung lay, Burmese-style pork belly curry from Northern Thailand with these things in it. And then we would explain what it was that they were eating and why. So I think that the access that people got to that kind of food was easier than if they had flown to Las Vegas, gone to Lotus of Siam and asked for the Northern Thai stuff.

Roads & Kingdoms: Did you meet Bourdain when he came to Pok Pok? Is that how that happened?

Andy Ricker: Much later. A couple things happened. Number one, I wrote a cookbook with JJ Goode. So I ended up with Kimberly Witherspoon as an agent. Not only did she have Tony, she had Daniel Boulud, she had everybody. And we met initially through Kimberly, and then later on he did the final episode of No Reservations, a Brooklyn episode. And I was in that, I came to the restaurant with Eddie Huang. And then later, when we did the Northern Thai thing in 2017, I pinged him and I was like, ‘Hey, man, I’m writing this other book. If you’re coming through the region, would you come and hang out?’ And I wasn’t thinking about the show. I was just thinking it’d be cool to have these people that I know in the food world come and eat drinking food with me in Thailand, and then have that be part of the cookbook. And I got a couple sentences back from him saying, ‘Yeah, man, that sounds great. Let’s make a show.’ So we ended up doing a week in Chiang Mai together, that was the second time around.

Roads & Kingdoms: And was that also when you hooked up with Roads & Kingdoms?

Andy Ricker: I actually didn’t really get close to them until he died. We met face to face I think for the first time at Tony’s wake. And then there was a lot of correspondence about doing something eventually. And the way that I came to actually work with them was that I got invited on the first League of Travelers trip in 2021. And then at the end of that, they were like, so do you want to do a Northern Thailand trip? And then after that trip, Nathan (Thornburgh, R&K co-founder) was like, ‘Hey, would you be interested in potentially hosting trips in other places besides Thailand?’ And I said, sure. And that morphed into, ‘Hey, would you be interested in scouting?’ And now here we are.

The restaurant world was already in crisis before Covid hit. People don’t want to remember that.

Roads & Kingdoms: You shut down Pok Pok during Covid, right?

Andy Ricker: It was kind of a culmination of a bunch of different things. The restaurant world was already in crisis before Covid hit. People don’t want to remember that, but we were already facing all the things that we’re facing now. Covid just made it all worse. And I just looked at it and went, well, I’m one of those people who’s super leveraged, because I never had a financial partner. I never took on an investor. So all the money that was used for the restaurants was from the restaurants. I just looked at it all and I went, I can’t survive this. I’m probably going to go bankrupt, and it’d be better to try to get rid of everything while my employees are being taken care of by the government and while we’re in this rent deferment age. So in April of 2020, I started selling off leases and by probably March or April of 2021, I had sold everything. I got rid of it all.

Roads & Kingdoms: If you hadn’t moved so fast, that probably would’ve been a lot harder to do.

Andy Ricker: Yeah, I mean in April, people were like, ‘Oh, by June we’re gonna be open.’ And it was like, no we’re not. Are you listening to the scientists and the doctors? I was just like, I can’t do this.

Roads & Kingdoms: After you closed the restaurants, what brought you back to Thailand?

Andy Ricker: By the time Covid hit, most of my life, most of my friends, were actually in Thailand. So I had this network of people that I was close with that I’d known for close to 10 years. And of course, my wife was here, my cats were here. I had more of a normal life in Thailand than I had when I was back in the States. My wife would come occasionally, but it’s hard to just leave your house in Thailand. The weeds and the animals will come and take it away. So she would stay at home, and I would occasionally come over, but I would have to go back and work. And I was going from Portland to New York to LA when I was back in the States. So United States basically became a place that I went to work, and Thailand was where I went to be at home. So when Covid hit, it wasn’t like, I’m uprooting my life and moving to Thailand. It was like, I’m just getting rid of all this crap and I’m going home.

One of the things that served me well was understanding that what I was doing was treading into a treacherous culinary minefield.

Roads & Kingdoms: What does your life look like in Chiang Mai?

Andy Ricker: Number one, I do personal food tours here, so people can reach me via my website. I do the Roads & Kingdoms stuff. My wife and I have bought, renovated, and leased or lived in various pieces of property over the years. So we have four rental properties, and we’ve got a couple of pieces of land that are on the market to sell. So it’s kind of the same shit that I’ve done forever, just in a different place. For the last 30 years, I’ve been involved in building spaces. But I’d say that that was a huge part of my work at Pok Pok as well. I identified spaces, planned them, designed them, built them. So this is just an extension of that.

Roads & Kingdoms: Would you ever open another restaurant, or are you kind of done with that?

Andy Ricker: I pray every day that I never do. I have two spaces here, coming up on three now, that if you walked in and looked at, you’re like, ‘Oh, this is a restaurant.’ And the typical comment when people walk in is, ‘When are you opening?’ My answer is ‘Never, hopefully.’

Roads & Kingdoms: So what are these spaces?

Andy Ricker: I have a space that we’re moving into now that we’ve just renovated and built out, and it looks like a restaurant, but it’s a food studio. It’s where I go to develop recipes. It’s where we have private events. It’s where I do cooking classes. It’s where I sit and make bánh mì just because I want to. I have access to a professional kitchen all the time, which is great for me. So I can keep my feet in it, but I don’t want to open the doors and deal with the nightmare of employees and customers.

The typical comment when people walk in is, ‘When are you opening?’ My answer is ‘Never, hopefully.’

Roads & Kingdoms: When you’re bringing people through Thailand, for instance on your upcoming League trips to Southern Thailand or Chiang Mai, what are you trying to show people? Are there things that consistently seem to surprise travelers or expectations that you are actively trying to work against?

Andy Ricker: We try to come up with some sort of theme for every trip. And for me, the thing that I kept on saying on the first trip is: Thailand is not a monoculture. And that’s what’s always been part of my thought process, trying to show the outside world that Thailand is not a monoculture. Because if you haven’t been here and you haven’t been paying attention, and you don’t dig very deeply, you would think that Thailand is occupied solely by one culture that speaks one language, and the food’s all the same. And it really isn’t. Not at all. There are people from all over the place that live here, some who have been here for generations, some who have just arrived.

Roads & Kingdoms: There’s real diversity.

Andy Ricker: The food world is very, very diverse. The countryside is very diverse. And if people can walk away from this trip going, ‘Wow, I had no idea that there were Yunnanese Chinese living in the mountains… growing tea and making Yunnanese food. Or, ‘Holy crap, there’s this Muslim culture in the south of Thailand that has its very own style of food and culture,’ and there are many, many different groups of indigenous folks here that the government never talks about. I think that’s a huge thing in helping to get people to think about Thailand in a slightly different way.

Roads & Kingdoms: And these are stories that you can trace through the cuisine. Do people tend to expect something closer to southern Thai food and the northern Thai cuisine is more surprising?

Andy Ricker: First of all, there’s not just Northern and Southern. But this is something that has been really hard to communicate over the last 15 years. Even to the people who work at the New York Times, anything north of Bangkok is Northern Thailand, anything south is Southern. It’s like being in New York and saying it’s West Coast as soon as you leave Queens. And so just trying to get people to look at Thailand as not just a place where you go to the beach or to party or to check out the ladyboys or to eat pad thai. It’s like, look, this is a real place with really distinct regions, and there are no beaches in Chiang Mai and there’s no khao soi in Phuket.

Roads & Kingdoms: Is there a dish that you come back to the most, that you just love to eat or to cook? Or is this impossible to answer?

Andy Ricker: Like anywhere else in the world that has a great cuisine, it’s all about season, it’s about environment. It’s about the local cooking culture. If I’m in Phuket, I’m not looking to eat Northern Thai laab.

The food up here tends to be herbaceous, salty, umami-laden, meaty, but not sweet.

Roads & Kingdoms: What would you eat in Phuket?

Andy Ricker: In Phuket, you’re going to eat hokkien mee, a Chinese dish with oysters and pork. Or you might have the local Phuket cuisine, which involves the intersection of Peranakan cuisine with Southern Thai ingredients, coconut milk and that kind of thing.

Roads & Kingdoms: For the uninitiated, what is Peranakan cuisine like?

Andy Ricker: That’s the Chinese who immigrated to peninsular Thailand and Malaysia. There were the Malay people, and then the Straits Chinese, and then there’s the central Thai people. And so when the Malaysians and the Straits Chinese met, that’s where you get the Peranakan from. But also Phuket was where the royal court was, so there’s this influence from the royal court, which tends to use very fancy ingredients. It’s just a completely different flavor profile from the north. In the north, we’re in a mountainous area with rivers, and there’s obviously no seafood, so you can’t make fish sauce. There’s all the jungle herbs. There’s freshwater fish, there are frogs. And then there are chickens and pigs. So the food up here tends to be herbaceous, salty, umami-laden, meaty, but not sweet. There’s also an element of bitter to that. And there are no dishes up here that have coconut cream in them except for one, khao soi, which is a complete outlier and has nothing to do with the rest of the cuisine up here and it’s a relatively modern dish.

Roads & Kingdoms: What is a dish you’d find only in the North.

Andy Ricker: So like jor pak gad, this is a brassica, like a yu choy, basically. You boil it in a soup with fermented fish, tamarind, pork ribs, and salt until it becomes a stew, almost. And then you top it with fried shallots or fried garlic, and that there’s no coconut cream, there’s no fish sauce. It’s very much a Northern Thai dish. Whereas if you went down south and you wanted to have a dish in Phuket, maybe you’d have this very, very rich coconut curry, or you might have a squid ink thing.

Roads & Kingdoms: Is chili spice prevalent throughout the country?

Andy Ricker: Yeah, but it’s like Mexico—it’s not like everybody uses one chili. It’s like different chilies in different regions that have kind of mutated over the years, and they use specific chilies for specific things.

Thailand is not a monoculture. That’s always been part of my thought process,

Roads & Kingdoms: You haven’t had a typical chef’s career trajectory by any stretch of the imagination. How do you think working so many kinds of jobs has affected the way you see your work or your life. Do you think about it? Or is this just something that is.

Andy Ricker: It kind of just is. I came to being a restaurateur pretty late in life. I brought to bear everything that I’d done in life to that point to make it happen. And it was good that I had all those skills. The only one that I lacked really was bookkeeping. I had a stack of bills and I had a fucking checkbook, and that was it.

Roads & Kingdoms: Relate.

Andy Ricker: But I think what it did was it allowed me to go about things in a way that your average chef or restaurateur can’t do, which is that I was able to do things cheaper and I could see all aspects of what was going on in the place and how they affected each other. Mostly chefs are focused on the food and their staff, and that’s it. They’re not thinking about the giant picture of every little thing. And I was able to see the whole thing. I knew what was underneath the sheet rock, and I knew what happened when the faucet leaked. I knew how to fix that. I also knew, because of all the years I’d spent in restaurants, what not to do, that customers are likely to not enjoy. And I knew how to pick a comfortable chair to sit in. So there was this pool of knowledge that just naturally made me do things in a certain way I guess, which was unconventional.

Roads & Kingdoms: It probably gives you a little more of a kaleidoscopic view of the way people are coming to things.

Andy Ricker: I think so, and I think that one of the things that served me very well was understanding from before the get-go, that what I was doing was treading into a treacherous culinary minefield where I had to be sure that I did things with the most respect I could to the culture and to the food, and not to claim any of it as my own, to give credit where credit was due, that that was a very conscious thing that I did from the start.

Roads & Kingdoms: I think now there’s more of a mainstream understanding that you have to be culturally sensitive, but that was a little bit against the grain even 20 years ago.

Andy Ricker: Well, I just think it was because I didn’t go to Thailand for two weeks and come back and open a Thai restaurant. That happens. I went again and again and again for 13 years before I felt brave enough to open a chicken shack.

It’s frustrating, it’s corrupt, it’s a mess. But it’s also community, and there’s a vibe, and we have a great life here.

Roads & Kingdoms: How have you seen Thailand change? That’s a huge, broad question, but having spent so much of your life there, I wonder what kind of changes you’ve seen or that you’re seeing.

Andy Ricker: Obviously technology has changed. Infrastructure has changed, so everything’s much bigger and people’s tastes have gotten a lot more modernized. We’ve watched Bangkok go from being a provincial capital to… it’s a different country. It’s got its own economy. It’s light years ahead of the rest of the country as far as sophistication, availability of products, infrastructure, everything. Chiang Mai has grown. There’s a shitload of traffic. There’s a lot more people, but it still has the soul of a sleepy, northern Thai arty town. It’s got its problems, always has had its problems, always will have its problems, but ultimately it’s still got this soul that people are drawn to.

Roads & Kingdoms: Do you see yourself staying there long term?

Andy Ricker: Oh yeah. Although I am working on getting my Italian passport, so that just in case everything goes to shit, I can go move into the mountains of Sardinia or something like that. But right now, we just talked about it today, there are a lot of challenges being here. It’s frustrating, it’s corrupt, it’s a mess. But it’s also community, and there’s a vibe, and we have a great life here. You asked what I want people to get from our trips here, and one is it’s not a monoculture. The other one is that I always hope that people get little snippets of stuff they like. I love it when we’re on these trips and people go, ‘What is that thing?’ And it’s like an everyday thing that I just take for granted and I can explain it to them and they can go, ‘Oh, wow, I love it.’ This is what I like about traveling, when I discover something very small and insignificant, but it gives me insight into the place I’m at. And I’m hoping that people will just get these little snippets along the way or leave going, ‘Holy shit, what was that thing we ate and how can I make that?’

Roads & Kingdoms: I remember when I was backpacking, I used to make little lists of these things, just wonderful insignificant thing that you can’t find elsewhere.

Andy Ricker: In Thailand, it’s the thing you use to wash your ass. Now I travel and I’m just like, ‘You dirty, filthy animals don’t wash your ass.’ I hope everybody who comes here goes away going, wow, that was great. I’m going to go get a bidet seat as soon as I get home, so there’s one more clean ass walking around In America.

Roads & Kingdoms: I think we have our kicker. Thank you, Andy.

Want to travel with Andy? Explore our upcoming League of Travelers trips to find out where he’s headed or contact him directly through his website.