From plov meccas to karaoke bars, from superlative bazaars to park life, a complete guide to Uzbekistan’s capital.

Two thousand years ago, Indian spice merchants and Chinese silk-sellers passed through Tashkent’s famous bazaars—at the meeting point of the Silk Roads—on their way to Europe. Uzbekistan, a predominantly Muslim nation, has a diverse cultural heritage, and Tashkent is cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic city, home to Uzbeks, Kazakhs, descendents of Mongol nomads, Armenians, Tajiks, and even (perhaps) green-eyed, red-haired descendants of Alexander the Great’s armies. Russians settled in the region when it was part of the Soviet Union, and Stalin’s mass relocations brought Koreans, Volga Germans, and Crimean Tatars. After the 1966 earthquake, which leveled most of central Tashkent, a wave of Soviet construction-workers arrived in the city, which still retains a Soviet flavor.

After independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, President Islam Karimov’s 25-year, authoritarian regime was criticized for its repression and human-rights abuses. But things have been changing for the better. Karimov died in 2016, and under its new president, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the once-secretive state has made some big political and economic reforms, and it’s loosened its grip a little on the press and freedom of expression. There is a cautious sense of optimism in Tashkent. Uzbekistan is becoming an exciting place to be—and travel infrastructure is improving all the time.

Know the rules. As of 2019, visa-free travel for up to 30 days is possible for citizens of 46 countries, including most of Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Another 76 countries can apply for electronic visas—but make sure you get everything in order in plenty of time. (For more details, visit the website.) Do collect a registration slip from your hotel; on your way out of the country, you’ll need to account for each night you stayed there. You’ll need a passport and your hotel registration to buy a Uzbek SIM card.

Get online… mostly. Most hotels and some cafes have WiFi, but it might be slower than what you are used to. The internet has opened up somewhat, but remains restricted. Sites such as Facebook and YouTube are sometimes inaccessible, so consider getting a VPN.

Get a map. Russian signs are written in the Cyrillic alphabet, and Uzbek is written in the Roman alphabet—except sometimes it’s written in Cyrillic, just to confuse you. Street names are in Uzbek. Make sure you download a map you can use offline (such as Maps.me) if you’re on the move. That said, while maps use Uzbek street names, in practice most people know places by their former Russian names. For example, Osiyo ko’chasi, near where I live, is better known as Moskovskaya. When asking for directions, fix on a landmark rather than relying on street names. Amir Timur square is useful for the center of town, and the Grand Mir hotel puts you in the right place for the restaurants on Shota Rustaveli street.

Speak like a local. Uzbek is spoken at home, but Russian is still the lingua franca in Tashkent, and most people are bilingual. A few words of Uzbek or Russian will be useful. In Uzbek, greet people with asalomu alaykum and say “thank you” with rakhmat. In Russian, “hello” is zdrahstvuytyeh and “thank you” is spaseeba. English isn’t widely spoken among the older generation, but you’ll find that Tashkent’s youth are more than happy to approach you and practice their English.

Pick your season. Tashkent’s temperatures, in theory, range from -10 degrees Centigrade (14 Fahrenheit) in the winter to 50 degrees Centigrade (122 Fahrenheit!) in the summer. Recent winters haven’t been that cold, but November-February can be sleety and bleak. In July, when the period of intense heat (chilla) hits, people exchange urban myths of traffic lights collapsing into melting pavements. If you come at the height of summer, expect to scuttle from air-conditioning to shade and do your sight-seeing in the mornings and evenings. Spring is the best time to visit (mid-April to early June) when Tashkent’s fruit trees blossom, the sun is warm enough for café culture, and the mountains are still visible in the distance. From late-August to mid-October you are almost guaranteed bright weather and the beautiful golden leaves of the apricot trees in the makhallas (traditional neighborhoods).

Carry a big wallet. Uzbekistan’s currency is the soum, and there are about 8,000 soum to the dollar, so lugging a wad of cash is unavoidable. Fortunately, 50,000 and 10,000 notes are now available, (when most notes were 1,000s, I used to have to transport my bricks of cash in a backpack). You’ll still need a large wallet for your small change. International credit cards are starting to come into use, but they are by no means widely accepted or reliable. Economic reforms have put black-market money-changing operators out of business, so you’ll no longer be hassled in the market. Instead, bring dollars and change them at any bank or big hotel. If you’re stuck, you can withdraw soum and dollars at most big hotels too, but the ATMs don’t always work, and you may need to try a few. You can’t take soum out of the country, so make sure you spend it all.

Go underground. The most practical (and picturesque) way to travel is on the Soviet-designed Metro, which criss-crosses the city and takes you almost everywhere you need to go. You are now, for the first time since it opened, allowed to take photos inside the metro, which is a bonus because every station is ornately decorated, some with intricate mosaics, others with chandeliers. (Check out the space-themed Kosmonavtlar station, with striking ceramic discs depicting Soviet cosmonauts.) A single ride costs only 1,200 soum, and you should buy a token before you travel. Expect to have your bag searched by one of the throng of bored police who guard the metro and monuments in the center of town.

Learn the road rules. Although Tashkent is somewhat sprawling, the center’s flat grid system is fairly compact and walking-friendly. But if you want to take a taxi, either flag down a metered yellow cab and name a landmark, or download the MyTaxi app. Taxi drivers probably won’t speak English or be able to read maps, but you may be able to guide them using hand gestures and Maps.me if you’re going somewhere they’re not familiar with (‘left’, ‘right’, ‘straight’ in Russian is naléva, napráva, priama). If you can’t find a taxi, you try just sticking your hand out and getting in a private vehicle. Name your destination and a price (between 8-12,000 soum takes you most places in Tashkent) and if they’re going in that direction, you’ve got a lift. Be aware that lots of drivers don’t wear seat belts, and few taxis will have them in the back seats.

Eat the best fruit in the world. From April to September, road-side souks overflow with succulent fruit and vegetables at tiny prices. April is strawberry season, and May brings red, black, and yellow cherries, as well as sour morellos. In June, stall-holders have peaches and apricots. July is for watermelons, August is for plums, with grapes, pomegranates, pears, and persimmons following in September and October. Central Asia is where apples originated, and you’ll find kées-lyi (sour) and slát-keei (sweet) apples year-round, with a much wider variety than most countries. Uzbeks, who love a good conspiracy theory, are full of horror stories about buying fruit too early in the season. I’ve been warned that June watermelons have been injected with chemicals to ripen them, but as long as you see the locals buying them, you should be O.K.

All you need is plov… A staple of Central Asia, but an obsession in Uzbekistan, plov (both a dish and cooking method similar to the pilaf and pilau of South Asia and the Middle East) is rice cooked in broth, with carrot, chickpea, and meat (mutton, lamb or beef). Here, it’s often lamb, including glistening lumps of lamb fat, flavored with cumin and barberries. There are plenty of tiny tucked-away plov joints in Tashkent, and you’ll find it at fine-dining restaurants too. But if you want to get the full experience and watch it cooked over flames in huge, steel cauldrons (callled kazans), go to the Central Asian Plov Center, a cavernous dining hall and celebration of plov dishes from around the region. Alternatively, try Uz Samsa Plov, just off Amir Timur square, where in the summer you can sit outside and eat your plov feast on a tapchan (a raised platform with cushions).

…but you don’t need to live on plov alone. Don’t despair if plov isn’t your thing. Try lagman, a delicious Uyghur noodle soup made with lamb; any restaurant advertising Milliy Taomlar (local cuisine) will probably serve it, but the Caravan restaurant on Abdullah Kahhar street is a safe bet. It’s tough to be a vegetarian in Uzbekistan (I should know!), but you could try asking for tikva (pumpkin) or kartoshki (potato) somsas. (Be warned that these might have been cooked in lamb fat, though.) Most Tashkent restaurants will offer Russian dishes alongside Central Asian ones (think pelmeni dumplings with dill, or borscht). Sultan Sarai on Shakhrisabz street is a good-value lunch stop, as is Ariston in Mirzo Ulugbek park. Shota Rustaveli’s B and B Coffee House is where the expats go for Sunday brunch.

Skip the wine. The local Sarbast Original lager beer and Russian vodka are good options. Most local wine is barely drinkable, and the price of the imported stuff will make your eyes water.

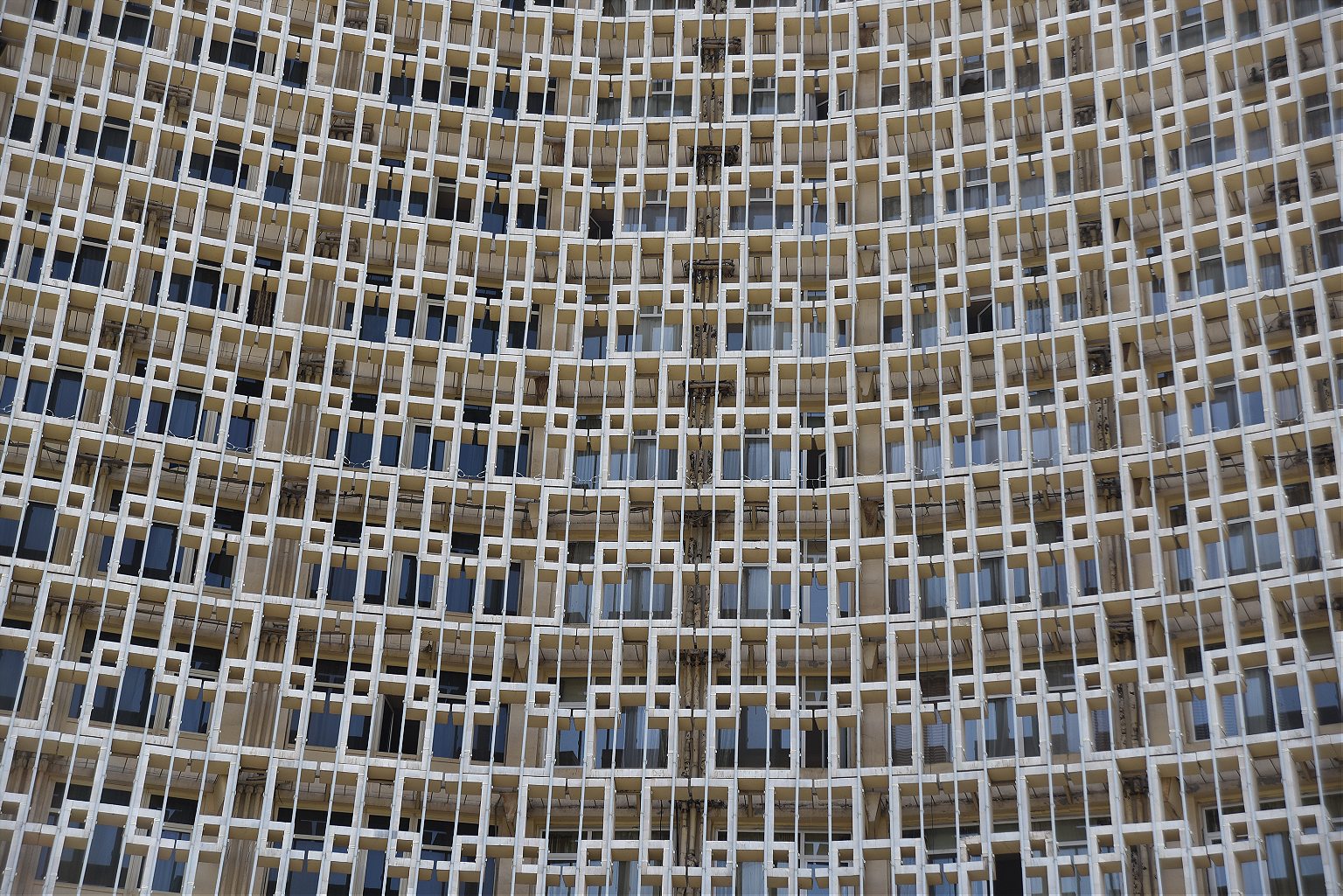

Fall in love with Soviet Brutalism. Love or hate the Brutalist style, it’s a big feature of Tashkent’s skyline. After the 1966 earthquake, hundreds of stark but functional concrete housing-blocks, hotels, and official buildings sprang up in Tashkent. Although the Soviet housing blocks are starting to look a bit run-down, they have beautiful mosaics featuring farm maidens, heroic cosmonauts, and Central Asian designs. A walk along Bobur or Mirobod streets is an easy way to take them in. There’s a particularly impressive set of Brutalist skyscrapers near Hamid Olimjon metro station, where Mustaqillik Avenue crosses the bridge. At night, they’re lit up with disco lighting, which might compromise the aesthetic but certainly brightens them up a bit. The gutted Hotel Moskva near Chorsu Market and the imposing Hotel Uzbekistan, with a design that resembles an open book, are also quite photogenic. The latter has a little top-floor bar from which you can look out over Amir Timur square while sipping a cold beer, vodka, or juice.

Know who Amir Timur is… Every Uzbek school child can tell you. Since independence, the powerful 14th-century conqueror Amir Timur has taken on enormous stature in Uzbekistan. Nation-building President Karimov chose Timur as the ancestral figurehead for his newborn country, rewriting its identity and breaking free from its Soviet legacy. This reclamation of national identity has spawned a wave of new books that claim Timur, and Central Asian scientists such as Ibn Sina and Al-Biruni, as ancient Uzbeks.

… and visit his statue. Severe and scowling, sitting astride an enormous horse, Timur presides over an eponymous square at the center of the city (a spot that used to be occupied by Karl Marx). Circumambulating Timur’s statue is a must, particularly to see how revered he is by Uzbek youth. Skip the museum, which is housed in the blue dome opposite—there are a lot of labels, but few artefacts.

Get counter-cultural at the Ilkhom Theatre. This independent theater (the first in Uzbekistan) was founded by the director Mark Weil in the 1970s, and actors from all over the Soviet Union flocked there to work with him. Weil was, tragically, murdered in 2007, but his vision for producing high-quality, experimental, and uncensored theater lives on. Just off Pakhtakor street, the Ilkhom stages adaptations and new work in Russian and Uzbek in its 100-seat black-box theater. Its brave, sometimes provocative productions seem all the more miraculous in the context of day-to day life in Uzbekistan, which has been strongly regulated. If you’re lucky enough to visit when they have a production with English subtitles, seize the chance. Once a month, the theater also stages a rock-fest, featuring local professional bands playing a blend of punk, rock, and ska with an Uzbek-Russian twist.

Walk along the canal. The Bozsu/Anhor canal runs east to west through Tashkent, and although it’s not possible to walk its entire length, some sections take you past some interesting sights. The canal is wide and deep enough that hardy locals swim year-round in places (the section near the Pakhtakor Stadium is a good spot if you’re so inclined). The longest walkable section starts by the gleaming new Minor Mosque and runs all the way down to Bobur street and beyond. Stepping away from the canal, you can visit monuments like the earthquake memorial and a jovial new statue of President Karimov, but if you stick by the water there’s plenty to see too. A little way from Minor Mosque, you’ll find a Muslim graveyard, each grave bearing a portrait of the deceased. You’ll pass a canoe club, where at weekends fierce coaches shout encouragement to athletes. A sluggish side-loop of the canal offers the Olympic Glory Museum, but the nearby restaurant is probably more tempting.

Find a bargain at Chorsu Bazaar… You can get to Tashkent’s oldest and most famous bazaar by metro (Chorsu station). Its big blue domes house acres of produce, from kazi (horsemeat sausage) to pickled kimchi. (Upstairs are dried fruit and nuts. The pistachios are imported from Iran and expensive, but the raisins, walnuts, and apricot kernels are cheap and delicious.) Outside, there’s a huge, covered fruit and vegetable market, and around the margins there are handicrafts, plants, and household goods. Chorsu is also a great place to pick up cheap ceramics. The quality might not be as good as a plate from the Fergana Valley, but with a bit of haggling you can get a beautiful salad dish for under $15. (Haggling tip: You should offer 50 percent of the seller’s starting price and be prepared to walk away.) In the clothing and fabrics section of the market, you can find felt slippers, embroidered bags, and beautiful suzani throws. Note: Chorsu is partly closed on Mondays.

…but don’t forget Yangiobad Flea Market. Grab a taxi at 6 a.m. on weekends and head for Yangiobad on the edge of town, a sprawling flea-market that has been threatening to relocate for years. Expect to clamber over railway tracks, elbow your way through shuffling crowds, and sift through piles of bric-a-brac, but if you’re into second-hand souvenirs, there are treasures to be had at tiny prices. Each section of the market has a theme: There’s an alley for tractor parts, a medical zone where you can find old Soviet dental tools and metal teeth, a bird and animal zone, and a section for old military and air-force uniforms. Soviet paraphernalia such as badges, flags, or statuettes, and Russian crockery is housed in the antiques zone. There are no maps, so you’ll need to ask a stall-holder for directions, or just drift through the market. You might even find a shabby but authentic Central Asian carpet for under $100. (Beware, though, that in the unlikely event that any of your purchases are considered precious national artifacts, they may be confiscated at the airport when you leave.) Some stall-holders may be offended if you photograph them, so ask before you snap. Although Tashkent has low crime rates, it’s a good idea to watch your pockets and bags in the bazaars.

Join the locals in a park. Don’t expect too much nature in an Uzbek park; rows of juniper trees are more the style, and in many places the locals hardly sit or walk on the grass. At the center of most big parks is a riotously loud fun-fair, and on warm summer evenings, Uzbek families throng to places like Anhor (on the canal near Minor mosque), Mirzo Ulugbek, or Bobur parks to stroll, spin their kids on the rides, eat fast food, and pose with fiberglass models of cartoon characters. It’s great people-watching.

If you’re going out, be prepared to pass ‘face-control’. Partying in Tashkent is a seriously dressy affair. Women are heavily coiffed and made up, in dresses and heels, though men can probably get away with neat jeans. Nightclub bouncers will size up your outfit, so err on the side of caution and dress to impress.

Embrace cover bands… A few years back, an unofficial curfew had bars closing at 11 p.m. and police ushering people off the street, but today there are plenty of places to eat, dance, sing, and party. A lot of restaurants have live cover bands (I heard the best version of “The Wall” since Pink Floyd in Gruzinsky Dvorik, the Georgian restaurant on Abdulla Kahhar street). Tashkent’s talented musicians perform in Russian, Uzbek, Spanish, French, and English. It’s a joy to watch families with grandmothers and toddlers alike take to the dance floor. Don’t be surprised to hear a lot of Boney M; they toured here during the Cold War and still have a special place in Uzbek hearts. The Steam Bar on Amir Timur street is where the student crowd hang out. You can hear music there most nights, and their resident band features one-time winners of Russia’s Got Talent (Minuta slavy).

… and karaoke. Karaoke is popular here. A high-class option is to rent a private room at Mona on Yusuf Khos Khodjib street and snack as you sing. Elsewhere, you may end up sharing a room with gaggles of friendly, vodka-ed up locals who will ask you to join them in a duet.