The assassination of Rio de Janeiro councilwoman Marielle Franco shocked the world. It may ensure black feminism is a national force at the Brazilian ballot box.

On a windy Friday evening in June, over one hundred people of mixed ages and races gathered in a concert hall in downtown Rio de Janeiro. In a part of town known for samba joints and nightclubs, they had come to hear five black women, all running for state assembly, discuss their proposals on jobs, security, and boosting political participation.

Candidate Mônica Francisco, 48, spoke with a soaring freestyle cadence honed over years as an evangelical preacher. Wearing long braids tucked into a massive blue turban, she said having more black women in politics would be good for all Brazilians. “Solutions designed by black women are solutions for black men, white women, and white men too,” she said, to cheers.

“We are here in a process sped up by the political execution of Marielle!” she added.

In October, Brazil will hold elections amid 12 percent unemployment, rising violence, and general disillusionment with politicians. And the figure of one woman—slain activist-turned-lawmaker Marielle Franco—looms large, driving many black women like Francisco to run for office.

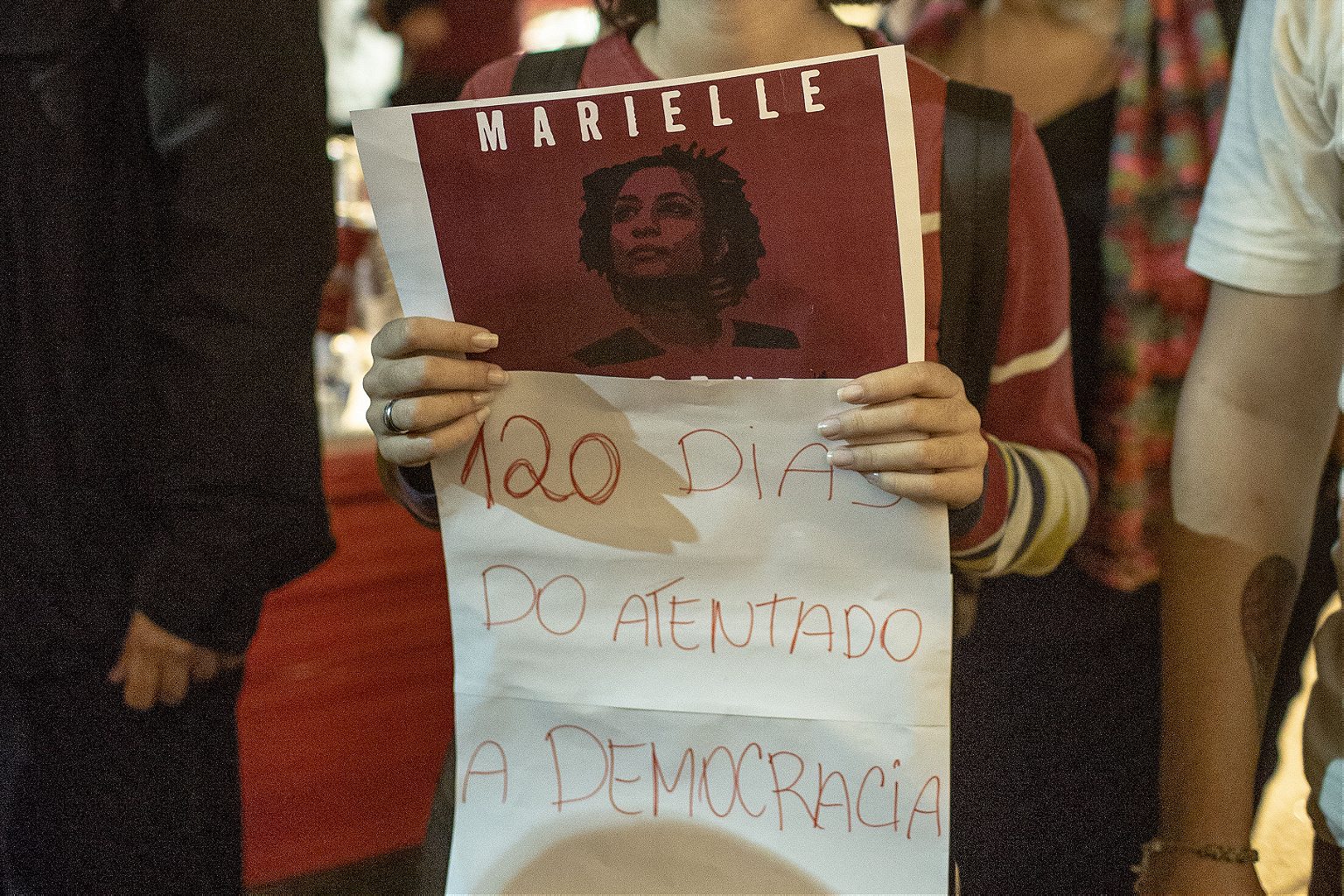

Franco was a local city councilwoman who rose to national prominence as a bright spot on Brazil’s Left. She was gunned down in March as she left a political event, sparking protests across the country. During a television interview earlier this month, Brazil’s Security Minister said the assassination “involves agents of the state.” Demonstrators have regularly gathered to demand justice for the 38-year-old’s killing, which remains unsolved.

From the depths of an economic and political crisis that could take a generation to undo, many Brazilians saw Franco’s killing as the elimination of a symbol of hope. Her image is now graffitied across Brazil’s cities, and streets have been renamed in her honor. Her name has become a rallying cry—both denouncing state compliance with slaughter, and insisting there is a political path forward.

A sociologist and an ardent defender of Rio’s poor, blacks, LGBTQ community, and women, Franco was one of Brazil’s very few black female politicians. Though black women make up 28 percent of the population, they comprise under 3 percent of state and federal legislatures. Black Brazilians are over-represented, meanwhile, among the country’s poor and victims of gun violence.

Not anymore, Francisco told the crowd in June. A former aide of Franco’s, she expressed confidence about her and her colleagues’ odds in October and their larger project putting more black women in offices long filled by rich, white men.

“If we don’t get there,” she continued, “more people will come in our wake.”

Brazil has been shaken by a social awakening in the last five years in which women, black people, LGBTQ people, and the poor—people like Marielle Franco—have demanded more from their elected officials.

In 2013, protests against public transportation fare hikes snowballed into massive demonstrations against the country’s endemic violence, inequality, and corruption, among other grievances. Millions of Brazilians had grown disillusioned with the ruling, left-wing Workers’ Party, which had been in power for a decade.

Over the next couple of years, conservative lawmakers asserted their power, introducing legislation that would reduce labor protections, send juvenile offenders to Brazil’s overcrowded adult prisons, and dramatically cut health and education spending. In 2015, Brazil experienced something of a “feminist spring” of women’s marches after members of Congress proposed legislation to make abortion—already illegal in most cases—more difficult to access (the bill passed in committee and still awaits a final vote). And in the years leading up to Franco’s election, Brazil’s long-building movement against racial inequality and police violence burgeoned among activists from Rio’s favelas and other low-income peripheries.

Related Reads

It was in this context that Franco, a longtime organizer with the Socialism and Liberty Party, decided to run for office. Her campaign team predicted she would earn around 7,000 votes and a position as an alternate on the city council. Instead, she won 46,502—the fifth-most of any candidate in the city (in Brazil, city council seats are not allotted by district; rather, residents choose candidates from an open list, and parties earn seats based on total vote counts). Franco’s massive vote haul helped her Socialism and Liberty Party grow its Rio representation from four seats to six. In the cities of Niteroi and Belo Horizonte, other black female candidates who ran similar campaigns also took surprise landslide victories.

In office, Franco continued to denounce violence and impunity in Rio’s favelas, which are home to around a fourth of the city’s population and where shootouts and police killings have risen in recent years. Last year on-duty police in Rio killed 527 people, according to government statistics, comprising a quarter of the city’s homicides.

Then, in February, Brazil’s government sent in military forces, purportedly to quell unrest, to take control of public security in Rio. The move raised widespread alarm in a country just three decades past its own military rule. Franco became a rapporteur of the city committee monitoring the actions of the military intervention, including any cases of abuse of force. She was also a rare public figure who openly denounced Rio’s milícias, powerful extortion gangs comprised mostly of ex- and off-duty police and firemen that control one fourth of the city’s territory.

Political observers have floated all of these facts as possible motives for silencing Franco.

On March 14, Franco hosted an event in downtown Rio about black feminism, got into a car to head home, and was shot four times by a drive-by gunman. She and her driver died at the scene.

Francisco, who had helped organize the event, had originally planned to ride home with Franco, but left early to meet her daughter. The two were on the way home when Francisco began to receive messages and calls. “It was the of the worst, most despairing moments of my life,” she said.

She said that while some colleagues mourned privately, staying home to grieve instead of attending marches in the wake of the killing, she kept in constant motion, moving between protests and public discussions, barely sleeping. After a few weeks and several conversations with family and co-workers, where they discussed the potential risks to her safety if she chose to follow in Franco’s footsteps, Francisco decided to run.

Thais Ferreira’s campaign office is set up in an otherwise unfurnished house in the working class Praça Onze neighborhood, about a mile from central Rio. The concrete walls are adorned with large, sticky note-covered maps of the state; a calendar ticking off the days until the election; and a strategy sheet outlining tasks for her 9 staffers and 95 volunteers.

Money is tight, and Ferreira said she may have to take a day job during the campaign. She figures she can make campaign pitches during her commute between work and her home in the outskirts of Rio. “Politics on the rails,” she said. “Gets your attention, right?”

Ferreira, 29, wears her hair in an upswept Afro and has a taste for bright colors and African prints. Before politics, she worked in fashion, opened a food truck park, and started a low-cost, pop-up maternal-health clinic. She said she wants to enact policies to help other lower- and middle-class Rio residents become entrepreneurs, and help diversify the state’s economy.

Though Ferreira only met Franco a handful of times, she said, “We immediately had an understanding of shared experiences as black women and mothers.” Ferreira has two sons, ages two and four, and Franco had a 19-year-old daughter. Franco invited Ferreira to discuss potential maternal-health projects with her staff and urged her to run for office.

“She always said, ‘it’s not enough for me to be here alone,’” said Ferreira. “‘There need to be more of us.’”

Ferreira and Francisco are now both candidates for Rio’s state assembly, running with Franco’s leftist Socialism and Liberty Party. (Because legislative elections are open, it is possible for the two women to be elected alongside each other). So, too, are former Franco staffers Renata Souza and Daniela Monteiro (pictured in the cover image, on the right). Urban planner Tainá de Paula and rapper MC Carol from the Communist Party of Brazil both cite conversations with Franco as reasons they decided to run for state assembly.

In Rio, black female candidates from a handful of leftist parties often appear at events, like the June discussion, together. Talíria Petrone (pictured in the cover image, on the left) and Áurea Carolina de Freitas, the councilwomen from Niteroi and Belo Horizonte, respectively, who were elected in 2016 are now both running for Congress. Even in the Amazon rainforest, black women are running Franco-inspired campaigns.

“We have to get away from the scarcity mentality [that says] there can be only one black woman elected,” Francisco said. She said Franco’s election showed that “with attention to the right language and issues, you can mobilize people who didn’t care about electoral politics before.” Though voting is mandatory in Brazil, many Brazilians cast blank ballots out of protest or apathy.

Nearly 20 years apart in age, Ferreira and Francisco are a generation apart and have campaigned accordingly. Ferreira is part of a young black pride movement that is sometimes referred to as “generation tombamento,” a term from a 2014 rap song that describes winning, dazzling, and honoring history. She recently appeared in a video chat on “Depressed in the Suburbs,” a popular Facebook page that jokes about life in the peripheries, where she mused about and compared iconic working-class foods: the hot dog at the Madureira hip-hop dance, in her measure, beats the bacon fries from the nearby Marechal neighborhood.

Francisco learned her politics two decades earlier, in grassroots discussion circles in Rio’s favelas. She says she has known “too many children of friends to count” who have been lost to violence. Though Brazil’s most vocal evangelical lawmakers are conservative, Francisco is appealing to progressive members of the faith, recently appearing on a Facebook Live webcast alongside a prominent progressive pastor. This internet exposure is particularly important for candidates appealing to voters in the favelas and peripheries, where criminal groups often restrict which political candidates can campaign in their streets. Unapproved door-knocking can be deadly.

Ferreira and Francisco both say that their agendas are similar to Franco’s: They want pathways to dignified work, greater police accountability, and functioning, high-quality public healthcare, among other things.

“Social movements and entrepreneurship are crucial,” said Ferreira, “but the added power of being able to legislate this agenda is too important to ignore.”

Ferreira and Francisco are running in what may be the most unpredictable elections since Brazil emerged from military rule thirty years ago. More than fifty members of Congress are currently under investigation for corruption, many of whom voted together to help Brazilian president Michel Temer twice dodge bribery charges. In Rio, budget shortfalls have meant months-long delays in paying public workers, including teachers and firefighters, sparking massive protests.

Nationwide, a right-wing political bloc is growing. Hundreds of current and retired police and military officers are running for office, and many are loyal to presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro, a retired army captain known for his praise of Brazil’s military regime, including its most notorious torturers. Though some of these candidates defend human rights, many hold a position that “a good criminal is a dead criminal,” shorthand in Brazil for a police approach of shooting first and asking questions later.

Those promises are popular. Bolsonaro is currently first in some polls for the presidential race, and some experts say the congressional “bullet caucus” of ex-law enforcement officials and lawmakers funded by firearm companies could double in size come October.

Related Reads

On the Left and center, self-described “political renewal movements” have been training potential candidates for months on the role of lawmakers and navigating elections. Some are financed by business titans concerned about Brazil’s economic stability; others are more grassroots and employ the language of Occupy Wall Street. For the most part, they comprise white candidates: of 133 trainees in RenovaBR, a program founded by an investment fund director, only two were black women (Ferreira was one of them).

Candidates like Ferreira and Francisco are hoping to gain from a new law and initiatives aimed at putting more women into office. In April, Brazil’s Supreme Court ruled that political parties must spend at least 30 percent of their campaign finance on female candidates (the previous requirement was 5 percent). They must also devote at least 30 percent of of their allotted television and radio advertising to female candidates. It’s a move that experts say could fundamentally change the electability of female candidates.

Earlier this year, a team of political scientists, sociologists, and statisticians launched a platform called “Black Women Decide” that presents data about black women in politics and organizes open events introducing black female candidates. The site’s co-founder, Ana Carolina Lourenço, said she and her colleagues want to dispel the myth that “few black women get elected because of a lack of qualified candidates.”

“Black female candidates have historically been made invisible [because] donors and political parties don’t choose to invest in them,” she said, adding, “you can’t choose what you don’t know is an option.” In 2014, only 2.5 percent of total campaign spending for Congressional candidates went to black women, though they comprised around 13 percent of candidates. Lourenço said her team is connecting volunteers with black women’s campaigns nationwide.

In July, Ferreira and Francisco traveled to Brazil’s commercial capital of São Paulo for an event meant to spread news of progressive activist campaigns from across the country. Dubbed “Occupy Politics,” it included candidates—many black and female—from Brazil’s southeast to northern shore.

One of them was 36-year-old Jo Cavalcanti, who is running together with four other women for a “collective seat” that they would share in the senate of the northeastern state of Pernambuco. Cavalcanti coordinates a housing rights movement that named its latest occupation of an abandoned building after Franco. “The person who killed Marielle didn’t realize they were stepping on an anthill,” she said.

The event included an activity coined “candidate speed dating,” in which attendees sat face-to-face with candidates to talk about their desires and ideas for their country.

Ferreira sat next to Áurea Carolina de Freitas, the councilor from Belo Horizonte who is now running for Congress. The two struck up a conversation, swapping ideas on how black female candidates from different parts of the country could support each other; and they made a plan to compile a composite video message.

“Marielle wanted to be an ambassador to black women,” said Ferreira, “and it makes me think about how you who are already occupying these spaces can be ambassadors.”

“Marvelous,” Freitas replied. “Let’s go.”