Sazan is the paranoia, secrecy, and militarism of Albania’s dictatorial past in reinforced concrete and iron. It’s also a gorgeous island that could boost the country’s economy.

Look out from Vlorë on Albania’s western coast and you see the island of Sazan—a gull wing silhouette about 10 miles distant, where the Adriatic meets the Ionian in the Otranto Strait.

If it’s clear, you can see the green of pine and fig trees layering its 1,000-foot peaks, then the pale filament of limestone cliffs along the shoreline. And in the days of Enver Hoxha’s communist rule, that was as much as any civilian was ever permitted to see. They knew it existed and did so at the center of a military exclusion zone. The rest was rumor.

It’s now an easy 30 minutes by boat from Vlorë to Sazan’s harbor, where rusted cranes lean from piers crumbling into the turquoise swell. There was still an hour of light left when I moored there recently with Albanian historian Auron Tare, so the tall, scrubby-bearded 50-year-old set off on his usual walk along the cracked road that doubles up from the harbor.

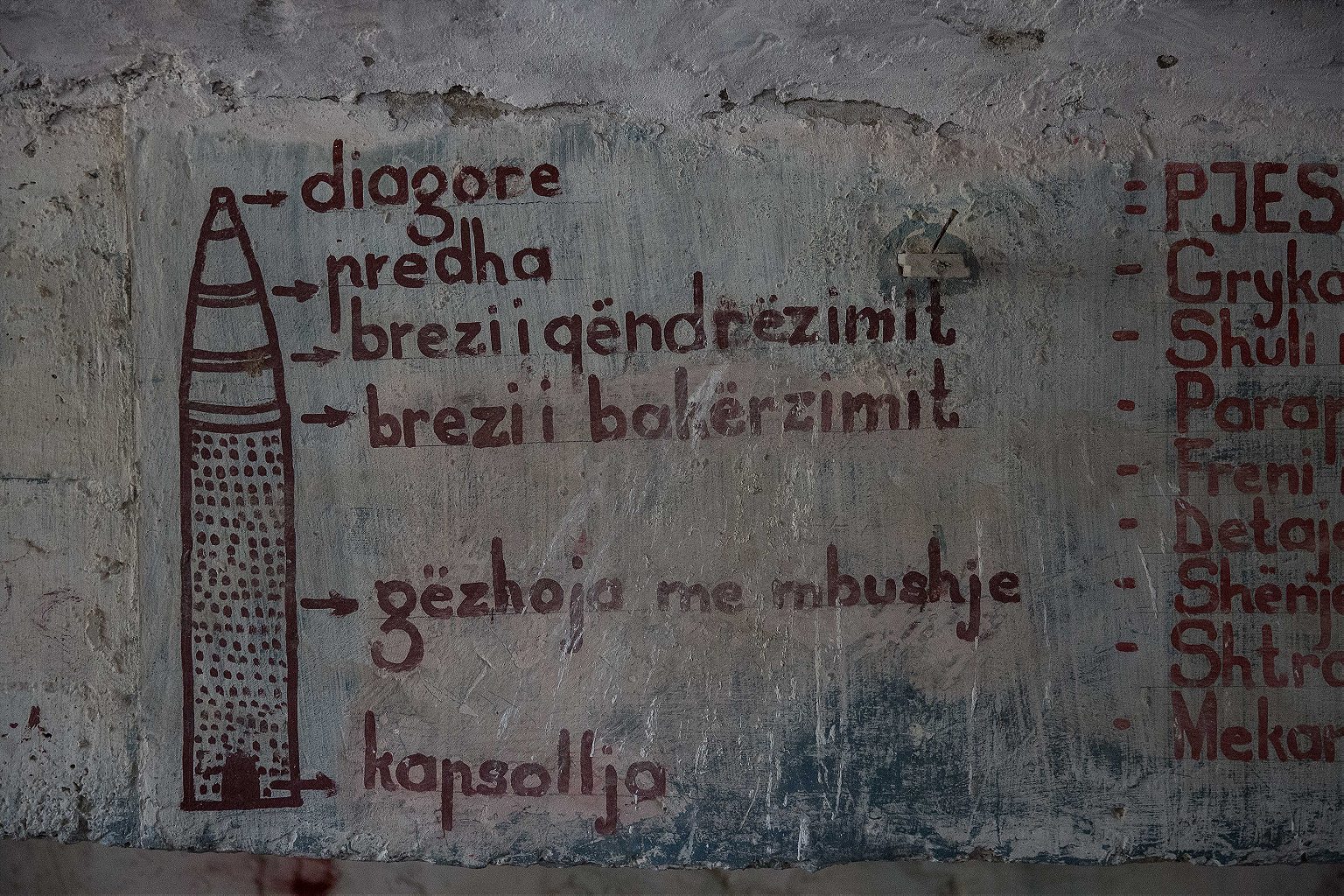

Domed pillboxes choked with shrubs and ferns overlook each turn, paths lead off to hardened artillery positions with the best views of likely landing beaches and littoral waters. Further on is a school with a large communist star in its grounds, stark apartments fronted by more pillboxes and a cinema that once screened weekly propaganda films. Below are bunkers designed to survive a nuclear strike. During the Cold War, the complex served a Soviet chemical weapons plant and submarine base. 3,000 soldiers and their families dug in there for an ever-expected invasion until Albania’s government collapsed along with the rest of the Eastern Bloc and there was nothing left to defend.

Sazan is the paranoia, secrecy, and militarism of Hoxhaism in reinforced concrete and iron. And when the dictator finally died, it became part of a past that many who lived under him preferred to let pass from memory. But Sazan is beautiful too: nine miles of unspoiled coastline, a climate far milder than the mainland, and an unusually varied array of plants and animals.

In that, Albania’s now-entrepreneurial leaders see opportunity. Tourism already contributes €1.5 billion to the country’s economy and there is room for many more visitors. Officials have suggested building luxury hotels on the island and converting bomb shelters into wine cellars. One failed bid mounted by a group of Las Vegas-based investors would have made it a giant casino.

Related Reads

The Defence Ministry finally opened Sazan to the public last year, allowing day trips between May and October. It’s still a military installation and occasionally shelters coast guard vessels hunting smugglers bound for Italy, but just a handful of troops guard it in shifts. The only other non-indigenous residents are two donkeys and a pair of bony, sand-colored dogs that have learned to greet newly-arrived ships in expectation of galley scraps.

For now, the island remains much as it was left. An officer’s mess obscured by pink oleander flowers contains hundreds of empty vodka bottles. There are desks and blackboards in the school’s classrooms, while Tare found paperwork and orders in a command center when he first visited.

The seal of Mussolini’s National Fascist Party marks the door of one older building built by the Italians stationed from 1914 until the end of World War II. The facade is scarred with holes and scorch marks that Tare says are the result of Albanian-British military exercises in 2013.

The exercises ended with at least 30 Royal Marines requiring medical attention and fears that they had uncovered another part of the island’s history in the form of a Soviet chemical agent. An investigation concluded that their blisters and burns were most likely caused by the giant hogweed that grows there.

Tare was appalled when he learned of the damage and called his old basketball friend, Prime Minister Edi Rama. The island should be opened to the public, not used as target practice, Tare told him. Rama agreed.

Tare, who has headed a number of other archaeological and architectural preservation projects in Albania, has proposed a management plan that would enshrine Sazan’s historical status. Unchecked development would risk much older heritage, too. The ancient Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, and Ottomans all recognized the island’s strategic value, and the surrounding waters contain the wreckage of thousands of years of battles and accidents. These too lie largely undisturbed. Fishing was banned around the island and when scuba diving equipment became commercially available, the Hohxa government banned it too in case citizens attempted underwater escapes.

Albania is still one of the poorest countries in Europe, and as its largest island, Sazan could become a lucrative resort. After decades of repression, welcoming foreign investors and building over the secret police, food shortages, forced-labor camps, and political killings is tempting.

It is a debate that surrounds other prominent communist buildings, like the bizarre Pyramid of Tirana, which was built in the capital as a monument to Hoxha in 1988 and been the subject of various plans for refurbishment and demolition since shortly afterwards. But its uncomfortable symbolism has made it hard to destroy and it still stands, derelict and graffiti-covered in the city center.

Remembering is important to Tare. Sazan, he believes, will help the country do that.

“The island is what Albania became, totally shut off from the world,” he shouted over the engine of his army surplus Landrover on the drive back to Tirana, where the Hoxha-era is an inspiration for bars and souvenir shops. “Young people don’t know what Communism was, but when you look at Sazan you know that this was Communism. It’s important that they understand that.”