In this rapidly industrializing Mexican border town, a group of die-hard suit fans are keeping a 1930s sartorial tradition alive—and reinventing it.

In the city of Ciudad Juárez, the streets are rife with industrial growth. Many have moved here from Mexico’s countryside to be close to the automotive and metalworking manufacturing boom. But one group of men and women still grasp at the past, keeping a tradition alive through the bold style of the Pachuco.

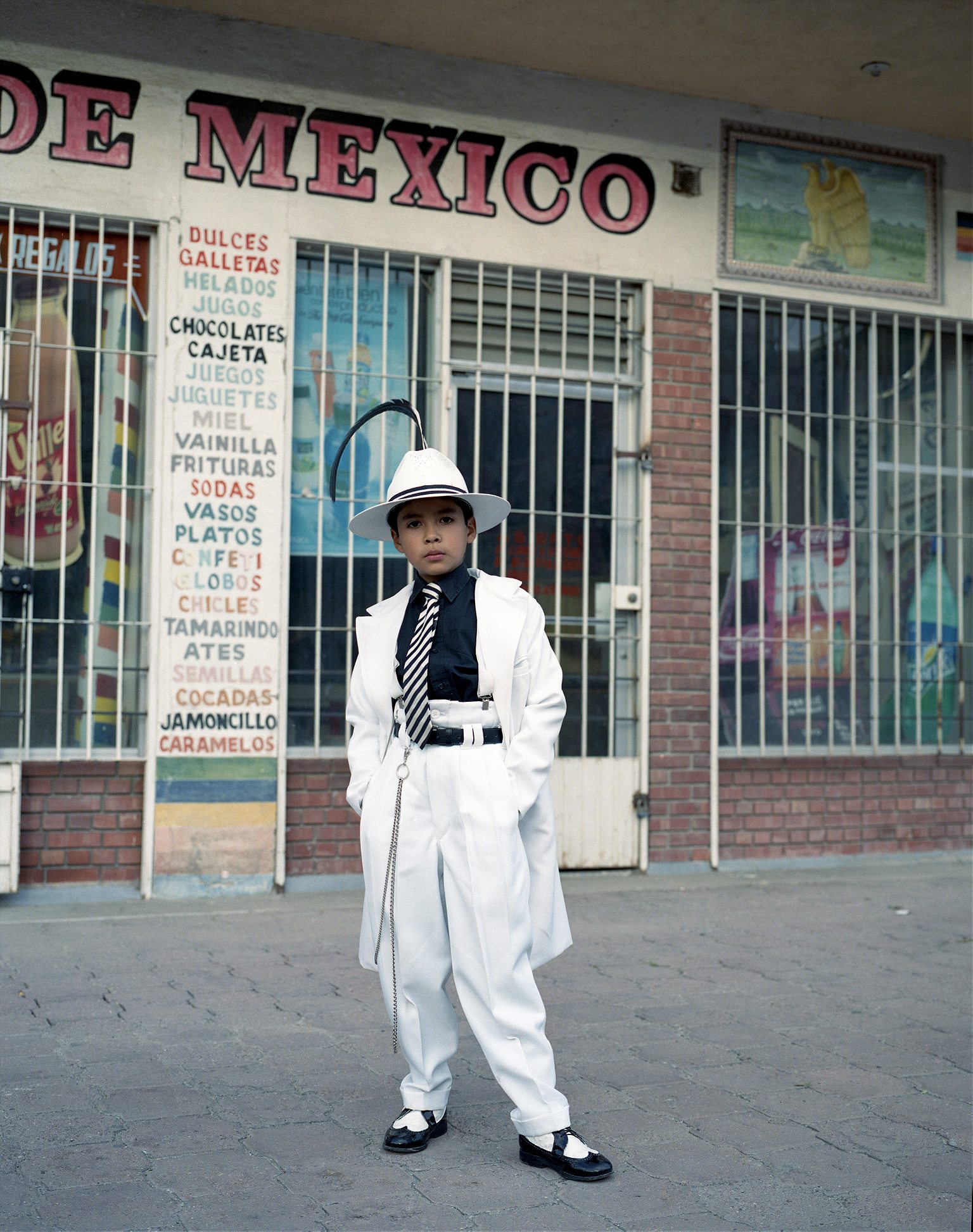

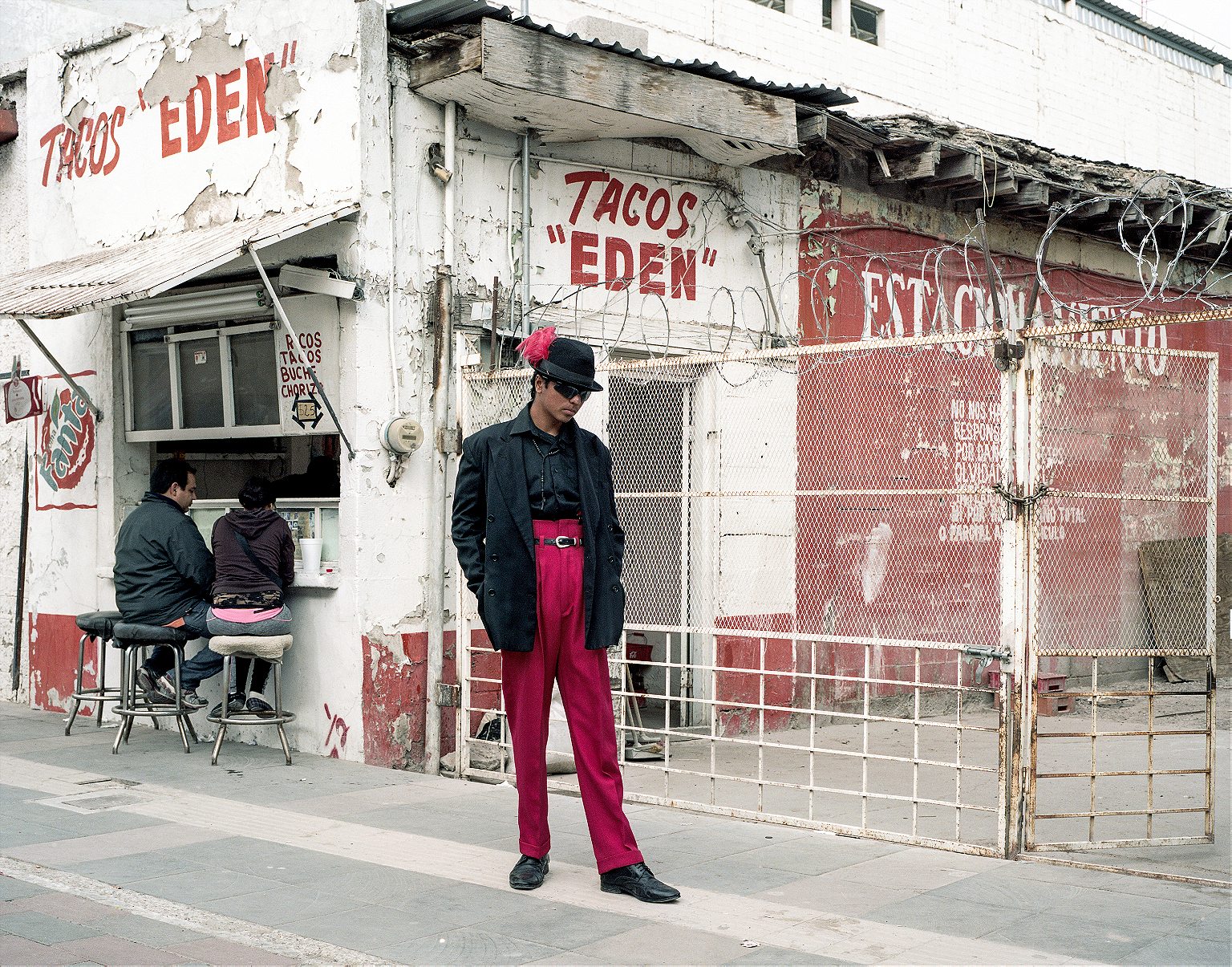

The Pachuco man came into vogue in the 1930s sporting the well-known zoot suit. The suits are marked by brightly-colored fabrics, oversized pants, cinched waists, and broad-shouldered suit jackets. Finishing the look was grease-slicked hair, long chains accenting the waist, and, often, in true mobster fashion, a concealed weapon.

“I went to Juárez just to find them,” says photographer Francesco Giusti about the 656 Group, a crew of modern Pachucos. Giusti spent about a month with the members, fascinated by the history of zoot suits and their gang associations.

In the past, the mobsters were usually Mexican-American men in their teens and early 20s. Their Pachuco clothing was a symbol of rebellion that originated in Texas and moved north to California, specifically Los Angeles, where the famous zoot suit riots of June 1943 occurred.

The riots were a string of brawls that broke out between Latinx in zoot suits and American soldiers, who saw the Pachuco’s flamboyant attire as a provocation considering a ban on wool was technically being enforced as part of the war effort. Tensions eased five days later when the U.S. military barred personnel from leaving their posts. Meanwhile, the LAPD proclaimed wearing a zoot suit to be a crime—not of fashion, but of political defiance.

These days, however, for the men and women of the 656 Group, true modern Pachuco style isn’t about being feared. It’s about being heard.

“The Pachuco today is not [just] the suit, but the attitude against discrimination in society,” says Miguel Compean Acosta, a stout man with a pencil moustache who favors his black-and-white checkered zoot suit, with a splash of color, of course.

There is a strong sense of belonging that radiates throughout the group, with shared values and a sense of community. “The Pachuco does not accept impositions in his way of thinking, nor in dress. He creates his environment; thus [he is] a rebel before society.” Yet for the group, it’s very important to use this boisterous presence for good. A lot of that entails charity work, and setting a good example for the younger generation; these are not the Pachucos of yesteryear.

Many organize dances and fiestas in the streets to raise money for social issues. “We deliver needed goods to churches and bring meals to the sick,” says David Villar, one of the founding members of the 656 Group. A thin, stoic man, Villar prefers the simple elegance of solid colored suits over patterns. He is often seen in primary colored wool pants with a black dress shirt, letting his attitude “speak for itself.”

For the dozens of members of Villar’s group, bringing honor to the city of Juárez, Mexico starts with style but ends with building a community.