This Moonshine Drinking Newspaper Editor Is Living His Best Life

This Moonshine Drinking Newspaper Editor Is Living His Best Life

Moonshine in Georgia

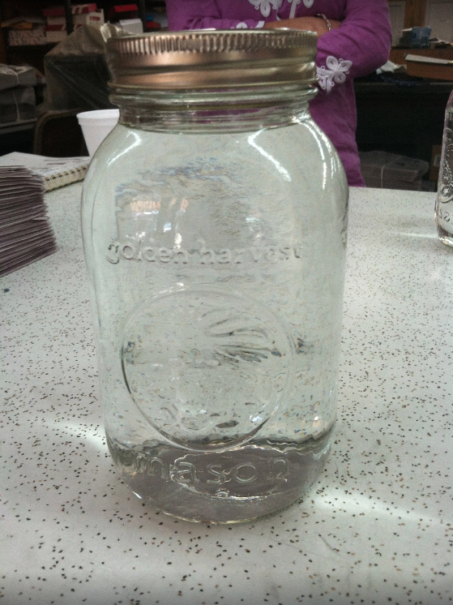

“Here you go,” the editor of the local newspaper said as he handed me a styrofoam cup full of clear liquid that had been poured out of a Mason jar. It was this peach moonshine, a patchy stray cat and a sign reading, “Greensboro: A Town of 3500 People and a Few Old Grouches” that welcomed me to Greensboro, Georgia. I didn’t ask where the hooch came from—in years past years it would probably have come from an illegal operation, but it’s hard to tell these days, particularly in rural Georgia.

I sipped it while he told me about the celebrities he’d met during his tenure and pointed to a signed photo on the wall of Kenny Rogers. Drinking the hooch, I didn’t have the choking reaction I expected, the one I remembered from my first tequila shot; this stuff was smooth. It wasn’t yet 4 p.m. and the staff of The Herald-Journal were already imbibing. I wondered to myself if they were hiring writers. Although I was in my home state, this was my first drink of Georgia moonshine, being a city girl. But it wouldn’t be the last.

If you grow up in the South, anytime you’ve got a number of men of a certain age together drinking, someone will pull out a jar of moonshine. It seems that just about everybody either has a family recipe or “knows a guy” who can get it. The corn-based whiskey is essentially what you get before barrel-aging bourbon, but there is a tradition of making it in copper stills on creeks and streams, away from the prying eyes of the ATF—the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives. It was usually offered in Mason jars used for canning vegetables, long before the jars became a mainstay in city cocktail bars.

This moonshine is common in the mountains of Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia. It was whisky bootleggers’ efforts to escape police—fitting out their cars to haul the contraband and then driving like hell to avoid getting caught—that led to the creation of stock car racing, which became NASCAR. Now, moonshine has evolved into a mass-produced item, but the glass in front of me wasn’t the unnaturally pink concoction you see at just about any liquor store. It didn’t have a label that said “Pappy’s” or “white lightning.” It was honest.

The next time I was offered the drink, I said no. It was 8 a.m. on Christmas Eve and I was at a mud bog with my dad, which involves driving specially outfitted trucks in a mud pit. The young guy who offered it had swigged out of the bottle plenty before we arrived. His eyes were blurry and his speech was slurred. I wasn’t sold on sharing. I bet he’d never even met Kenny Rogers.