New Jersey’s Portuguese community returns to Newark to celebrate their culinary heritage.

From the lower tip of Manhattan, Portugal is a 20-minute train ride. Take the gleaming white stairs of the Oculus down to the PATH train. Get off at Newark Penn Station. Exit onto Ferry Street. Walk east.

Sunday Mass at Nossa Senhora de Fátima begins at half past eleven. On a February morning that feels like a spring day, it’s not an easy task to remain indoors. Yet, as we hurry, late, towards the church on Jefferson Street, we walk on pavements devoid of passersby. We are in Catholic country.

Mass itself, is, well, Mass. The priest, clad in green and gold, gives a sermon in Portuguese to a group of almost three hundred attendees. Everyone is wearing their Sunday best, or perhaps I overstate: all the older people are wearing their Sunday best. From the back, the pews appear to be a sea of white hair, punctuated by some dark browns, some dyed blonds. Everyone recites the Nicene Creed, or the Credo Niceno, in Portuguese. It smells faintly musty in the style of today’s Western worship-house, increasingly a congregation of the aging and the aged.

The Church of Our Lady of Fátima is located in the Ironbound, a Newark neighborhood named so for the industry that surrounds it. The Ironbound, which runs east of the train station and south of the Passaic River, has been home to wave after wave of immigrants for almost two centuries. The 1800s ushered in the Irish and the Germans, many of who have since departed the city for richer suburbs. Today, it is home to Ecuadorians, Brazilians, Peruvians, and—the reason I am here—the Portuguese.

Bryan, my husband and the son of Portuguese immigrants, nods towards the door, signaling that we should leave a few minutes early to save seats for lunch. As soon as Mass is over, the attendees will make their way down Ferry Street for lunch at one of the many Portuguese restaurants lining its corners. At Seabra’s Marisqueira, a favorite among Bryan’s family, it is hard to find a seat after 1 p.m., in either the sun-lit, boisterous front of the restaurant, or the vast dining hall in the back. Our party of six gets seated near the window, from where I can see a roof-mounted TV playing RTP, the Portuguese channel, on mute.

A soccer match is on, punctuated by advertisements for canned tuna—the kind Bryan buys, not the “watery garbage” they sell at Whole Foods. The radio plays Justin Bieber staples, which you can barely hear over the day-drinkers at the bar and the waiters by the kitchen. Here at Marisqueira, the diners might be quite diverse—Portuguese families, American buddies out for some sangria, Brazilian couples—but the waiters are exclusively Portuguese. They all have near-identical haircuts and the same proud postures. They all look like they would rather be elsewhere. No one here will smile and tell you that his (yes, they are all men) name is Manuel and he’ll “be your server today.”

As far as food goes, you can’t do much better than Marisqueira around here. Their specialty is seafood, and their bacalhau a lagareiro, salt-preserved cod drenched in olive oil and served with garlic, onions, and potatoes, is some of the best I’ve had. When you’re married into a Portuguese family, you eat a lot of bacalhau. Today, we order the filhetes fritos instead: fried fish with rice and a salad so simple and fresh that even in this family of carnivores, it’s the first plate to be cleared up. As we eat, Rosa Maria Santos, Bryan’s mother, ruminates on why Portuguese food has not fared as well commercially as its closest counterparts. It’s not trendy like the Spanish tapas taking over New York City one $15 patatas bravas plate at a time. “And yet,” she says, “it’s expensive to make. It’s all seafood, it’s all fresh. It’s not like Italian, where you can buy some spaghetti, put a little bit of meat on top, and call it a day.”

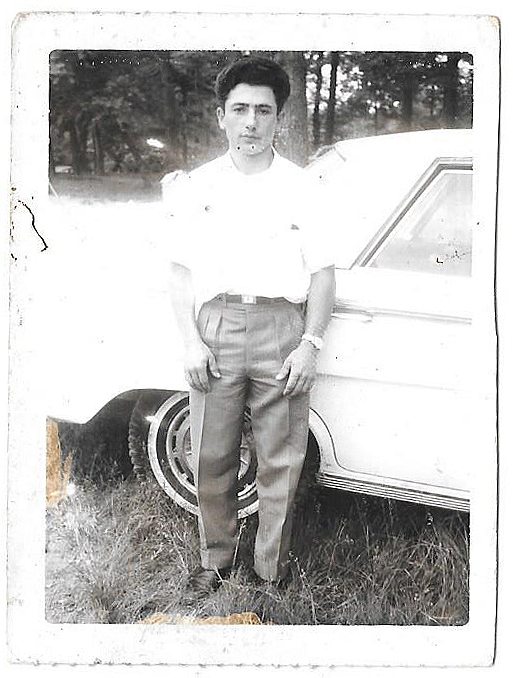

Next to Mrs. Santos sits her father and Bryan’s grandfather, Senhor Nelson Pinheiro. He was born in Brazil in 1941 to Portuguese parents who were living for a time in the former colony. When he was five, his mother died and his father moved back to northern Portugal, where Mr. Pinheiro lived until 1962. That year, he became one among the thousands of Portuguese emigrating out of the country, out of the grip of António de Oliveira Salazar’s regime. The authoritarian and conservative Salazar, who ruled Portugal for 36 eventful years that saw the Second World War and the Colonial Wars in Africa, is a much-debated figure in Portuguese history. In 2007, half the country chose him as “the greatest Portuguese who ever lived” on a RTP television show; the other half howled in dismay and anger. The Portuguese are grappling with his legacy to date, but what we do know is: during his time, there were many that left the country, especially the rural and jobless north, to find work abroad and avoid conscription.

Some of them went to France or Switzerland, but many traveled across the Atlantic. These immigrants hailed not from Lisbon or Porto, but from the countryside and the lesser-known regions of Portugal: they were the Serranos, the Minhotos, the Bairradinos, and the Murtuseiros. The people of the Azores had started coming much earlier, having settled in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and California in the 1800s. By the end of the 1960s, there were more than a dozen cultural clubs in Newark, each representing its own region of Portugal. By the end of the 80s, roughly 60 percent of the Ironbound, around 50,000 in number, were of Portuguese descent. Overall, between 1961 and 1980, almost 200,000 Portuguese immigrants arrived in the United States.

“On Sunday, I came here. On Tuesday, I was working,” says Mr. Pinheiro as we wait for the next course. For his first year in Newark, he worked at a paper factory, earning $1.15 an hour. The next year, he switched to construction and worked alongside immigrants from Poland and Italy, earning $3.15 an hour and hoping daily that it would not rain. “No rain, no pay,” he says. “No vacation, no sick days,” adds his wife of 53 years, Bryan’s grandmother Gracinda Pinheiro, from across the table. She would know; at 16, the youngest age that you could drop out of school, she started working at a garments factory in Newark. Bilingual education, today a key feature of the city’s public schools, wasn’t all the rage in the 60s. At the garments factory, language was not a problem; most of the women working with her were Portuguese, too.

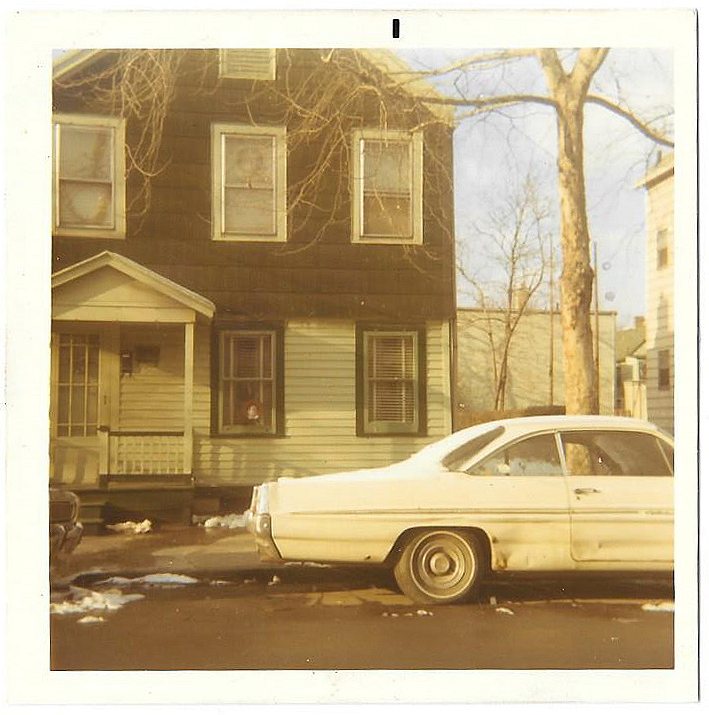

When the two of them got married in 1964, Mr. Pinheiro gave up his weekly contract at Roque e Rebelo, a Newark restaurant where workers could get a week’s worth of meals for $14. For more than a decade, they lived in a two-family house on Kossuth Street, next to German Catholic neighbors and not too far from the Portuguese afternoon school. Their television was strictly American, though, and so was a lot of their food. “We ate hamburgers and lasagna,” remembers Mrs. Santos.

But that is not what we are having today. The waiter comes over with bife a Portuguesa, steak and Spanish potatoes soaking lazily in the most satisfying sauce made of garlic and bay leaves, topped with an egg. The rest of the table also shares the íscas de fígado, pork liver cooked in a vinha d’alho style, with red wine and garlic. It’s clearly the biggest hit here, but I abstain: refraining from pork is often the last boundary for many Muslims like me, one that few of us ever cross.

It is at this time that someone mentions the word “saudade.” There are a few wry looks, and I hear a sigh. The word, dear to the Portuguese, can perhaps be translated as a vague but constant longing for something, be it a homeland or an imagined past. At the heart of this feeling lies the acknowledged impossibility of attaining what is longed for. The Portuguese insist on the idiosyncrasy of the word, on its untranslatable nature. I was born and raised elsewhere, too, so I know a thing or two about saudade. Perhaps it was this feeling that made the Pinheiros move back to Portugal in the 80s.

The 1960s had seen the Portuguese come in as construction and factory workers, often illegal immigrants living in the shadows, sometimes accepted as hardworking white Europeans, sometimes dismissed as illiterate, old-fashioned foreigners. The 70s, however, saw a military coup in Portugal, with more entrepreneurs and professionals migrating into Newark. Ferry Street was now lined with Portuguese businesses. In 1979, the city had its first Portugal Day parade.

“It was raining, remember, pai?” Bryan’s mother asks Mr. Pinheiro. “I can still see the headline from the Portuguese newspapers that day. “Choveu em Newark, mas não nos corações dos Portugueses.” It rained in Newark, but not in the hearts of the Portuguese people.

Work hard, stick together, make money, and GTFO

And yet, the family returned to a farm in Portugal in 1983. “That’s what everyone thought they would do,” the Pinheiros tell me. “You come here, you make money, and you go home.” Their tone, particularly that of Mr. Pinheiro, is frayed with the monotony of repeated storytelling; this is an episode of his life he has narrated many times. How his family returned to the homeland after two decades abroad. How disenchantment quickly followed. The kids had a hard time adjusting. The living was not as comfortable. “I wasn’t a farm girl anymore,” Mrs. Pinheiro shrugs. I ask if they ever considered moving to a Portuguese city like Lisbon or Porto.

“What would we do there?” It’s a strange idea to her.

“No, no,” Mr. Pinheiro shakes his head. “That is good only for the big shots.”

And so, barely two years later, they packed up yet again and returned to America. Again, they started from scratch: new china to eat on, new beds to sleep on. This time, however, they did not move to Newark. It was now the Portuguese immigrants’ turn to “upgrade”: following the footsteps of the German and the Irish, they were fleeing the concrete of Newark for the suburbs. Next stop was Kearny, a town across the Passaic from Newark, made famous by the Satriale Pork Store from The Sopranos. As Bryan likes to tell me, his family attained the American dream, Newark edition: “work hard, stick together, make money, and GTFO.”

The Pinheiros were the last in their family to move out of Newark, and yet they keep coming back, like many others. As we leave Marisqueira, its tiny corridor now lined with waiting customers, I wonder how many of the Sunday regulars here are emigrants out of Newark: people like the Pinheiros, who have moved on from a city reminiscent for many of grittier days. Mr. Pinheiro worked in Newark’s construction for 35 years, the physical toll of which is evident; aching bones keep up him many nights a week. For them, and many others, Newark was where the struggle of being an immigrant was the harshest, the strain of being away from home the keenest. Despite these memories, or perhaps because of them, the Pinheiros like visiting the Ironbound. Returning here is both an ode to the past and a nod to themselves: they made it in America.

Today, of course, there is a lot more to bring one to the Ironbound. A once dull neighborhood of factories is now a vibrant and prosperous area. Business is booming on Ferry Street; you can see it in the weekend lunch lines at Marisqueira, the tills at Seabra’s, the Portuguese supermarket, and at Portugalia Sales, a store that sells exquisitely kitschy souvenirs handmade from terra cotta and blue tile. Today, younger Portuguese-Americans like Bryan visit eagerly for the fresh bread and the aged queijo, the $1 espressos and the warm pastéis de nata.

Immigration from Portugal has stemmed since the 1980s, however, and the new guys in town are the Ecuadorians, the Brazilians—initially lured here by the Portuguese—and other Latin Americans. More and more storefronts promise, “Hablamos Español.” A day after the current President’s executive order on Jan. 27, the Archbishop of the Newark Diocese and the mayor of the city promised to maintain Newark’s status as a sanctuary city. Bumbling dictates, hastily signed, face an uphill battle against the Ironbound and all that it represents: centuries of economy and prosperity exported through the exiles of the world.