Echoes of a deported people can still be heard on the banks of the Volga – if you listen carefully.

“Volga Germans? You’re too late, they’ve all gone! Poshli!” laughed a Saratov taxi driver. Ivan, owner of an antiquarian bookshop on Kirov Street, Saratov’s main retail street, suggested I would have better luck searching in Moscow for information on this vanished community, even though we were just across the river from what used to be the Volga Germans’ own republic (a history of distant Bashkortostan, meanwhile, stood proud on the bookshelf behind him).

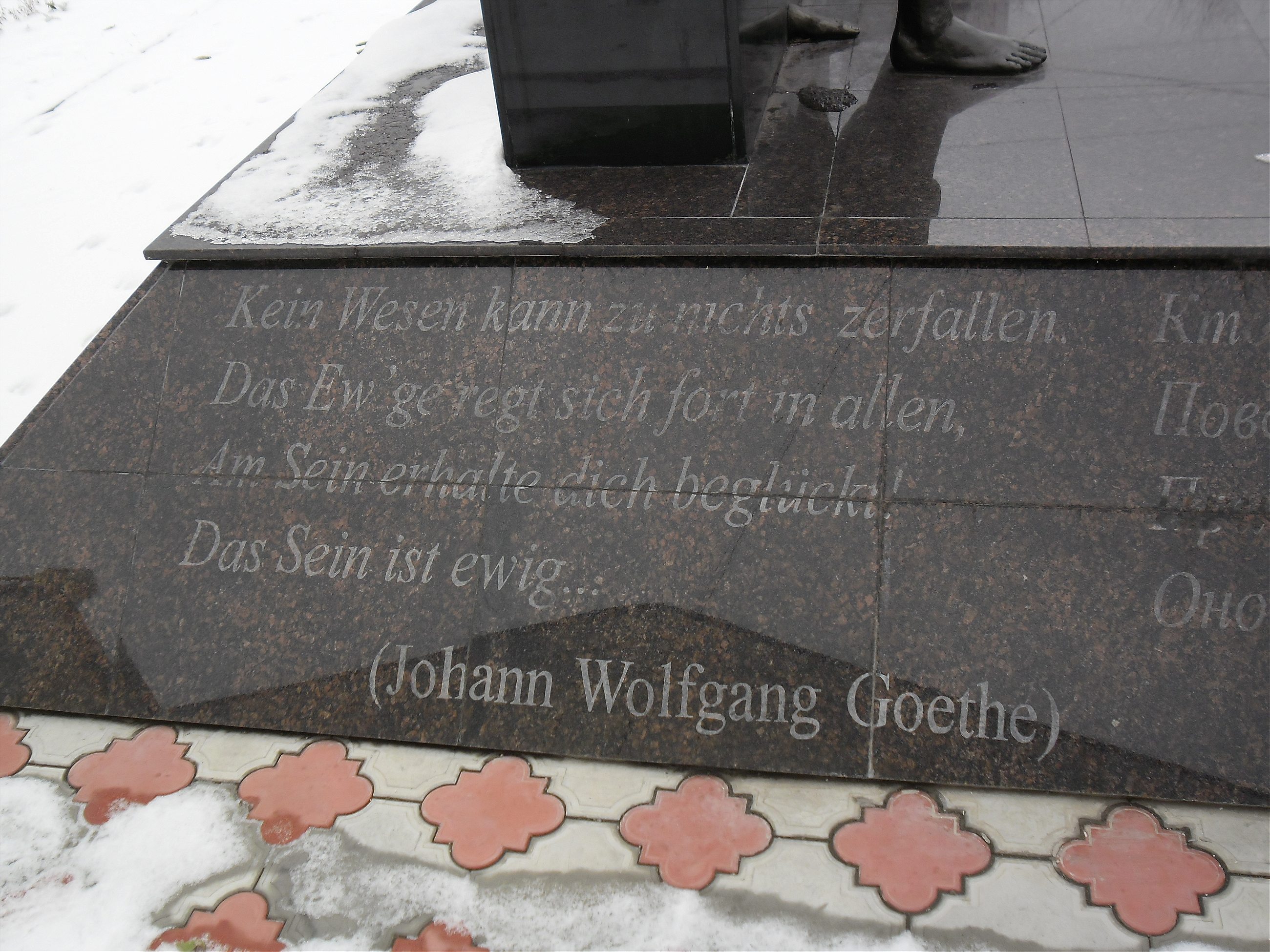

In the Khrushchev era, other nations that Stalin had exiled for alleged disloyalty during the war years had returned home from Siberia and Kazakhstan. Ingush, Kalmyk, Chechen, Balkar are all part of the modern, federal Russia. Yet the rehabilitation of a community of Germans who lived for centuries on the banks of the “Great Russian River” before Stalin sent them to Kazakhstan and elsewhere presents an ongoing conundrum for the Russians. Saratov, upstream from the site of the bloodiest battle in human history at Stalingrad, spares nothing in commemorating of its contribution to the war effort. Yet in August 2011, the opening of a memorial to the exiled Volga Germans across the Volga in their former capital of Engels was met with a mixed reception. From Crimea to eastern Ukraine, issues of ethnic identity and resettlement continue to shake the former Soviet Union, but the story of the Volga Germans seems destined to remain forgotten.

‘Russian Germans – victims of repression in the USSR’. Monument near the local archives in Engels, whose construction caused local controversy. Photo: Maxim Edwards

Saratov’s pedestrianised high street, once known as Ulitsa Nemetskaya (German Street) offers few clues to the region’s once large and vibrant German community. Renamed in honour of Kirov, and with the city’s main Lutheran Church replaced by a movie theater, Saratov’s German connection has more to do with modern German corporations. The city bought used German buses for its public transport, with German-language advertisements remaining on the windows. The city is home to a German honourary consul. Engels, meanwhile, is home to a large Bosch factory, which is an important employer. But the Germans who lived here earned just a modest exhibition in Saratov’s regional museum, which features copies of the ‘resettlement’ decree in two languages. But does postwar Saratov, the city of Gagarin, where thousands of people from all ethnicities lost their lives in various forced resettlements, owe them more? The surprisingly well-funded and attended German community center in Engels is a start. Advertisements for a German language choir for young people of German descent, the Wolga-Heimat (‘Volga Homeland’) choir, are on the wall. So are photographs of octogenarian German villagers from the region, beady eyed and headscarved, every inch the Russian babushka, but with their own story to tell.

The story, for now, seems mainly the preserve of ivory-tower academics of German descent. The few in-depth works on the subject were all published by the Internationaler Verband der Deutschen Kultur, and the Volga Germans remain a German subject for a German audience.

Modern Saratov might lack any discernible “German Character”, but there are still Germans here. Brothers Eduard and Yevgeniy Dolotov, sons of a German mother and Russian father, remained in the city after the deportation. The brothers’ maternal grandparents, the Goldswirt and Zartorius families, were German Protestants from the Volga region, and it was through research into their family history that they began their interest in the Volga German community and its connection to their lives.

“On the eve of the deportation that year,” says Yevgeniy, “if the head of the household—that is to say, the father—was a German, the family was sent away. I had a German aunt who was widowed. Her late husband was a Russian—it was only this that saved her from being sent to Kazakhstan.” On the question of identity, older brother Yevgeniy, who still has vague memories of the eve of deportation, sees himself as a Russian. Younger brother Eduard, however, feels that more of a connection to German identity. It is Eduard who has investigated the Volga Germans’ political history, and he is very assertive about the true reason behind opposition to the monument in Engels. “At the beginning of the 1960s, a small number of Germans who had been able to return wanted their properties back. However, by then, their houses had been taken by families evacuated from Ukraine. In part I think it’s a case of some families fearing commemoration of those whose houses they live in.” The Volga German Republic, founded in 1919, was founded on a contradiction: A workers’ republic for a nation of agrarian, devout Christians. Yevgeny says that the Republic was partly created as a political move, to encourage German support for the Bolsheviks. Yet local Bolsheviks were few and far between.

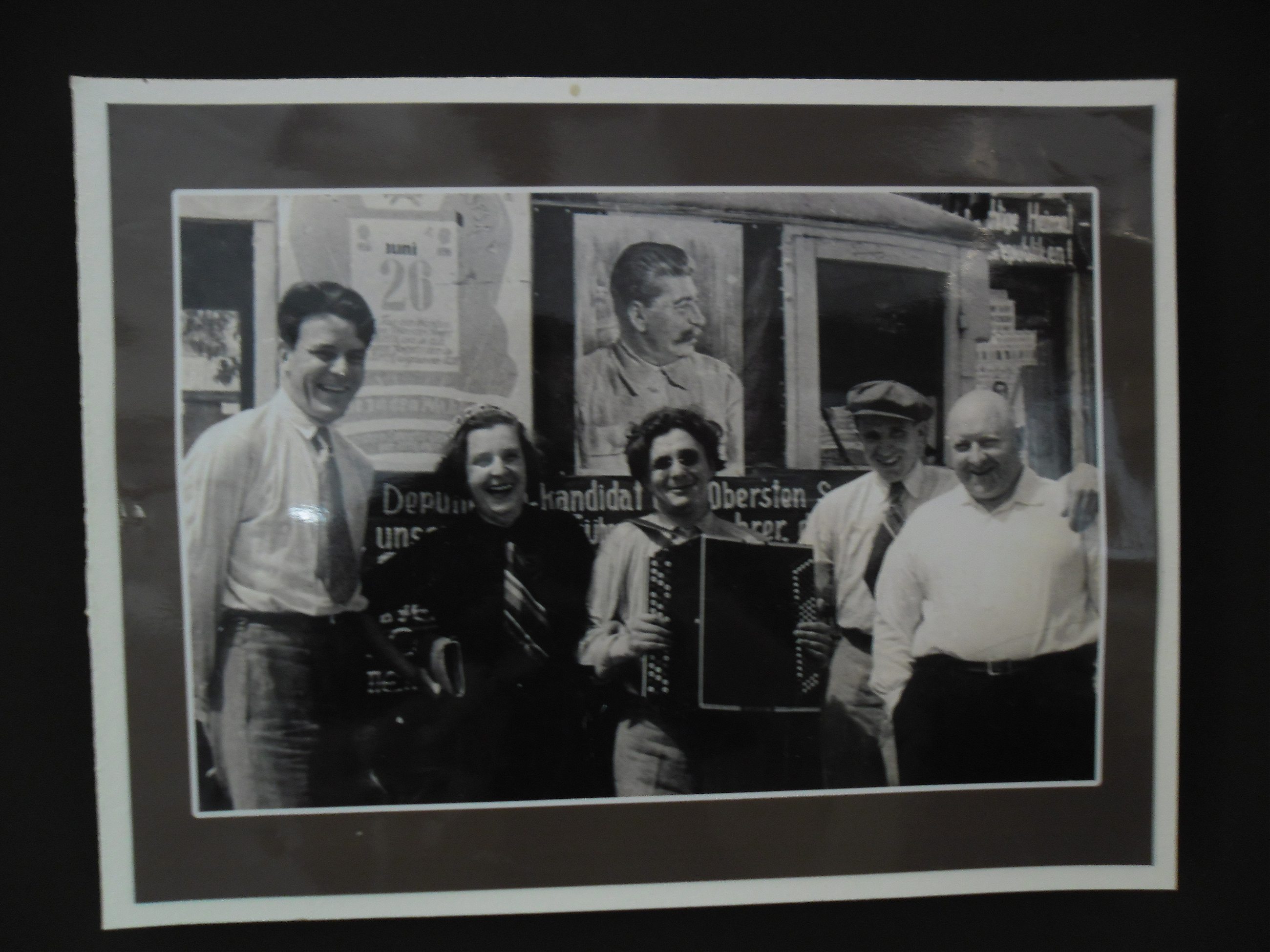

Many of the leaders of the Volga German Republic were in fact German Communists from Europe, one of whom, the President Ernst Reuter, would later become the mayor of West Berlin. The local museum in Engels plays a repeating black-and-white Soviet film set in a Volga German village, starring a conniving priest and his Kulak compatriots. Wooden Lutheran churches rise out of the steppe in black and white photographs as propaganda banners hung across municipal buildings praise Bolshevism in German Fraktur script. The architecture, which belongs in the Weimar Republic, not the bleak steppes of the Lower Volga, seems to underscore the alien nature of the Volga German presence. Small wonder that their survival under a government which viewed their very ethnicity as traitorous became impossible.

The question of whether the Volga Germans survive as a group is open for debate. Efforts in the late 70s to create a German republic in Kazakhstan failed. With the fall of the Soviet Union, the Germans didn’t go back to Saratov; rather, they took advantage of post-unification German laws that allowed them to immigrate back to Germany. They had been deeply Russified by then, but adopted German names and took German government-sponsored language and culture classes while trying to rebuild German lives in the homeland. For them, as for others who left for the Americas and elsewhere, they survived mainly by not remaining Volga Germans at all.

“I don’t think I know of one country where I haven’t had visitors from,” says Yelizaveta Yerina, director of the German Archive in Engels. German-Argentinians recently visited, she says, though actual support from the German government itself comes mainly in the form of publishing local research on the subject. An employee of the archives since 1967, she says a lot has changed since the Soviet era, when there was freedom to write about the deportations but limited freedom to publish and or publicize the issue. What is most remarkable, however, is the extent to which Yerina stresses the context under which the deportation occurred.

“Life was difficult for every nationality in those days. Did the Tatars live well? The Russians? The Kalmyks? I would see a monument for every deported nation. For the Balkars, for the Chechens—but this is not to say their suffering was any more worthy of commemoration than anybody else’s.”

Indeed, the monument itself, engraved with German-language poetry and dedicated to victims of the deportation (the local Communists in Engels held a protest as a result, stressing that it was “merely a resettlement”) also bears the words “to the memory of victims of political repressions”. Yerina, of German ancestry herself, is resolute that the suffering of the Volga Germans should not be exploited for political capital. “We commemorate what happened because we are Germans,” she says at the end of our meeting. “Not because we believe our suffering is exceptional.”

There is something of a beautiful irony in the renaming of the city of Engels. It was called Pokrovsk when it was the capital of the Volga German Republic, and was only renamed after the communist ideologue Friedrich Engels after the deportation had taken the Germans away. In their flight, the city’s identity has been transformed, its name a living memory to an ideologically acceptable German. But a German nonetheless. The Germans in Engels are by and large a phantom presence, a people of archives and faded photographs. Perhaps the city’s name, which derives from the word ‘Angels’ in German, is now more appropriate than ever.

[A version of this story was published in the late, lamented Kazan Herald, Tatarstan’s English language newspaper]