Estonia’s ethnic Russian minority find themselves in limbo as tensions with Moscow rise.

TALLINN, Estonia—

It is a bright day in late August and everyone in Tallin seems to be rushing to the center of town, where celebrations are underway for the 25th National Restoration of Independence Day. The public holiday commemorates the events of Aug. 20, 1991, when Estonia surreptitiously declared independence from the Soviet Union which had occupied the country since 1940.

The clear sky dotted with white clouds echoes the blue and white of the Estonian flag. On a stage in Freedom Square, choir after choir perform folk and contemporary songs in vibrant traditional dresses. It all looks very picturesque: a peaceful, small country, and member of the European Union since 2004, successfully reviving its cultural identity, quashed for 50 years by Soviet occupation.

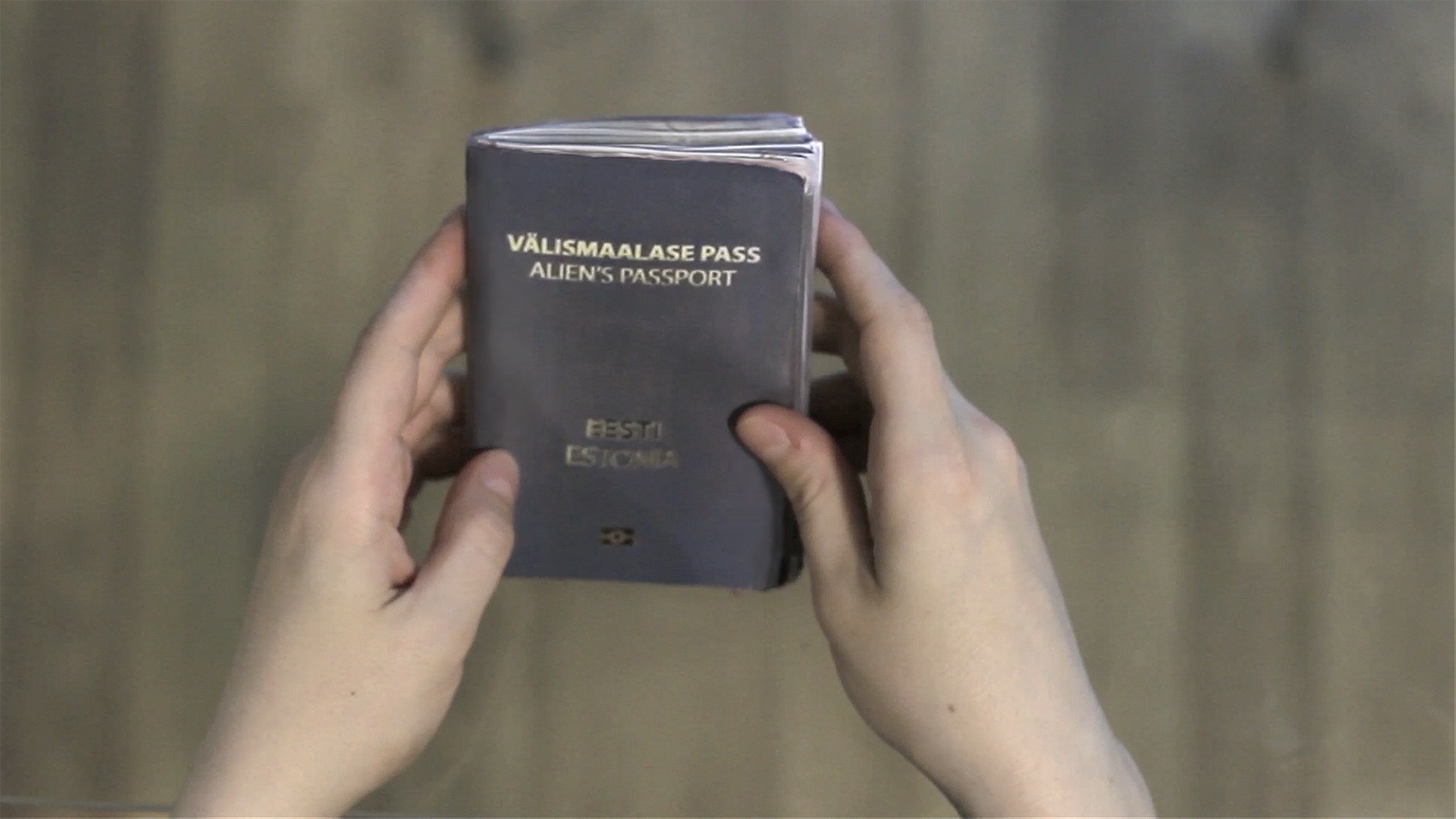

I join Elisabeth Haljas, and Vladimir Petrov, both 23. Haljas is ethnically Estonian, Estonian is her mother tongue, and she is able to take full advantage of her EU passport. Petrov, on the other hand, is from a Russian-Ukrainian family and he carries a gray alien’s passport issued by the Estonian government.

An alien passport may sound like a joke, but it is a complicated reality for ethnic Russians in this Baltic republic, as the country’s anxieties about its much larger neighbor grow. When Estonia gained independence, ethnic Estonians were given citizenship in the new state. But those ethnic Russians now living on the wrong side of the border—32 percent of all the country’s residents in 1992—found themselves in a political and geographical gray zone. The new government forbade dual citizenship, which forced ethnic Russians to make a difficult choice: either take the risky step of getting a Russian passport, limiting options (and rights) in Estonia and potentially uprooting families that had been in the country for decades, or apply for Estonian citizenship. In the meantime, they were classified as stateless and issued gray alien passports.

At the time, Estonia was anxious to reverse years of deliberate Russification by Moscow and limit the influence of Russia over its territory, but what was meant as a temporary measure has become an enduring reality. More than 25 years since independence, Estonia is still home to thousands of stateless people. Estimates put their number between 80,000 and 90,000, a visible minority in a country of only 1.3 million and the world’s 10th largest stateless population.

While a good number of ethnic Russians have successfully become Estonian citizens or acquired Russian citizenship, many have not. While the advantages of citizenship in an EU member state might seem obvious, the naturalization process is long and difficult, and it requires fluency in Estonian, a complex language with 14 cases which many people living in along the Russian border do not speak at all.

Petrov was born in 1993, after independence, but stateless status is hereditary: he has been, as his passport puts it, of “undefined citizenship residing in Estonia” since birth. In 2016, the citizenship laws were amended to automatically grant citizenship to newborns in the country unless their parents choose to opt out, but for Petrov and thousands of stateless others who are already adults, it was too late.

“Travelling within the EU is not too much of a problem, but working there is a whole other matter,” Petrov says. “You cannot stay for more than a few months anywhere, so effectively we must be in Estonia. And here lots of people would like to look for work in countries which pay better, like Finland or Sweden,” an option open to anyone with a E.U. passport. “I need a visa to go anywhere, even those countries which welcome almost any tourist. It makes you feel like there is something wrong with you, or that you are some sort of criminal or Russian spy.”

These are not the only restrictions: the stateless community is predictably cut off from political life. Only Estonians can vote in national elections or stand for a seat in parliament. Alien passport holders can vote in local elections but cannot be members of a political party, work in public offices and in some other positions. To make matters worse, for many jobs, including in the private sector, the law requires fluency in Estonian, via a certificate of language proficiency, shrinking further the number of jobs non-citizens can apply for. Unsurprisingly, unemployment among the stateless is 1.5 to 2 times higher than amongst Estonians, and they are also overrepresented in the prison population. There is one silver lining: those with gray status avoid conscription in either the Estonian or Russian army.

I ask Petrov, who works in the IT industry, if he feels Estonian. “Estonia is where I am from, what I knew growing up,” he says. “I am even fluent in Estonian. But this country has given me a lot of problems. I am going to apply for naturalization because I think it will make my life easier. In the end, I don’t think it really matters which passport I have… I was born in Estonia, from a Russian-Ukrainian family. That’s the end of the story.”

Petrov’s story casts a politically charged shadow on today’s festivities, which are all about celebrating Estonian values and identify. Even the choirs singing on stage have a nationalistic bent: the country’s secession from the U.S.S.R. was known as the Singing Revolution, in which gatherings to sing patriotic songs in the Estonian language turned into large crowds assembling in opposition to the government.

Haljas has been listening quietly. She has not faced any of these problems. “In my eyes, the Russians here tend to divide into two categories,” she says. “Some are rigid about their own ways of living, refusing to integrate, to be included in a free country. Others, instead, become part of society and it is all good. Some miss the USSR and are convinced life was better then, others are happy in Estonia.”

Kristiina Keelman, a 24-year-old Estonian who works in one of the many IT startups in the capital, agrees. “For me, the real issue is the minority who is not interested in Estonia at all, and is informed by the Putin-leaning, untruthful Russian media only,” she says. “On the other hand, many Russians are welcome contributors to our society and I really feel that they have made our country and society richer. I admit that as I am from a younger generation, my views might be more positive than for the people from older generations who have lived under the communist regime.”

While Petrov is seeking to change his stateless status, thousands of others will continue to use their gray passports. Vassily, not his real name, a 37-year-old Alien passport holder, is from Narva, a town by the Russian border with one of highest concentration of stateless residents. He is hesitant to talk about his circumstances and seems suspicious. “This situation is just stupid,” he tells me. “I don’t speak Estonian because I live in a Russian town. I don’t have the opportunity to practice. I have many Estonian friends; they speak the Russian language very well.” I ask him if he feels Russian or Estonian. “I feel human,” he answers. “When Estonia was last part of the U.S.S.R., I was 11 years old. What do you think I can remember?”

Vassily is not alone: Many Russians and Estonians, are reluctant to talk about gray passports. Locals seem to have resigned themselves long ago to accept this fragile but lasting compromise between the two groups. What is surprising is that the European Union has the same reluctance. Alien passports raise thorny questions about displacement and statelessness. Some international bodies, like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch sporadically make some short-lived noise about the stateless population, but for a variety of reasons, there is no great incentive to change the awkward status quo.

This may not be an option for much longer. Moscow, has, in the past, used the tactic of Passportization as a mean of of pressuring and dividing its neighbors. First, Russia distributes thousands of passports to ethnic Russians living in these neighboring states. Protecting the rights of these citizens then becomes a pretext for intervention. The strategy was used in Georgia’s breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia prior to the 2008 war and there were reports of it being used in Crimea prior to the 2014 annexation as well. The protection of these minorities was used by Russia as a pretext for both military operations. The ongoing marginalization of gray passport holders makes Estonia vulnerable to this kind of interference as well.

Amid rising tensions between the two countries, Russia announced in November that soon all stateless passport holders would now be able to enter Russia without a visa, not only those born before 1992.

Gray passport holders continue to live in limbo

Perhaps motivated by these concerns, Estonia, is taking some of the most drastic measures in years to integrate gray passport holders, trying out an easier Estonian language test in addition to the new rules granting automatic citizenship to residents at birth.

All this is happening as Russia’s perceived threat to Estonia has been growing. The country, and its Baltic neighbors have been asking NATO for assistance and the alliance has agreed to deploy forces to Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Fearful of Russia’s superior military strength, the government has also been promoting the creation of the Estonian Defense League, a group of civilian volunteers who regularly train in order to efficiently act as partisans in case of an invasion.

“I have always been a bit cautious about what Russia is doing, because they have the manpower to do whatever they want,” Haljas says. “I am not sure anyone could stop them without a major catastrophe worldwide. But until recently, I did not perceive it as such a big treat.”

For now, the uneasy compromise continues and the gray passport holders continue to live in limbo, not quite belonging to either country. What’s unclear is whether this uneasy compromise will prevent the kind of confrontation with Russia that other countries have faced, or provoke it.