Thanks to gourmet chefs and TV cooking shows, Parisian knife grinders are experiencing a revival.

Standing by his mobile workstation—an old British black cab equipped with German grindstones placed on a table over the back seat—Marius waits for customers bringing their dull knives, scissors, ice skates, and the occasional Japanese sword.

Three years ago, when he left his cooking job, Marius, 54, traveled to London with a friend to buy the car. “It’s part of the marketing. It brings people,” he says. The car, with 35,000 on the odometer, is now equipped with a small washstand and foldup seating. Once, a British tourist tried to hail him as he drove through the streets of Paris. “It was too funny, so I drove her until her destination,” he says. “But I didn’t make her pay.”

There are only a dozen traveling knife grinders—rémouleurs—inside the metropole. It’s an old fashioned job with a modern twist, as over the years electric-powered grinders have replaced the vintage hand-cranked versions. In the old days, Parisian knife grinders tried to lure clients by ringing bells in the streets and screaming, “Knife grinder! Knife grinder!” Nowadays, word of mouth or a phone call is sufficient, but it takes time to get rolling in this niche market.

Like other professions, knife grinders have fallen victim to technological change and globalization. Many knives today are made from stainless steel and do not require sharpening. But famous chefs, butchers, fishmongers, and hairdressers still require good, sharp knives. Moreover, along with the boom in TV cooking shows, other culinary-minded individuals are increasingly buying fancy kitchen equipment.

That’s where Marius comes in.

“You need to gain the chef’s trust. Knives are one of their most precious tools,” he says. “They move from restaurant to restaurant with their own set of knives, which can cost up to 200 euros each for the best ones.” (Marius’ actual name is Didier, which he considered too unimpressive for the knife grinding trade. “It’s my grandfather’s first name. Mine is Didier Mouche. ‘Didier the Knife Sharpener.’ It does not sound good.”)

This morning, Hubert Ardouin, a 25-year-old commis chef at L’Atelier de Robuchon, one of Paris’ priciest restaurants, gives Marius five knives that he desperately needs to be in good shape to slice julienne vegetables, fillet fish, and bone pieces of meat for the lunch service. “It’s the second time I’ve called him. It’s convenient. He comes to where you are,” Ardouin says. And it’s not expensive: 3 euros for scissors and a 5 for a knife.

Almost a year ago when Thierry Coursier, who goes by Titi (knife grinders have a thing with nicknames), decided to leave his job planning the circulation of commercial boats along the Seine, he called Marius. “He’s the first guy who comes up when you Google ‘rémouleur and Paris,’” Titi says. The 40-year-old with dark haired had seen a TV report about Marius’ success and “was tired of sitting behind a desk and a computer.” He wanted to find out more about the rémouleurs revival before making any big decisions about his future.

At different times in their lives, Marius and Titi both attended the same knife sharpening classes in the Gers, in the southwest of France. They spent two weeks learning the mysterious and sparkling alchemy of carbon steel: how to press the knife against the wheel to roughen up the blade’s edge, and how to then smooth the surface.

They also learned how to differentiate between knives that are sharpened with an acute angle between the blade and the grindstone and those sharpened with an obtuse angle. Marius already knew the ropes. “When I was younger,” Marius says, “I used to sharpen knives with my grandfather. And I was practicing it at the cooking school with my classmates.”

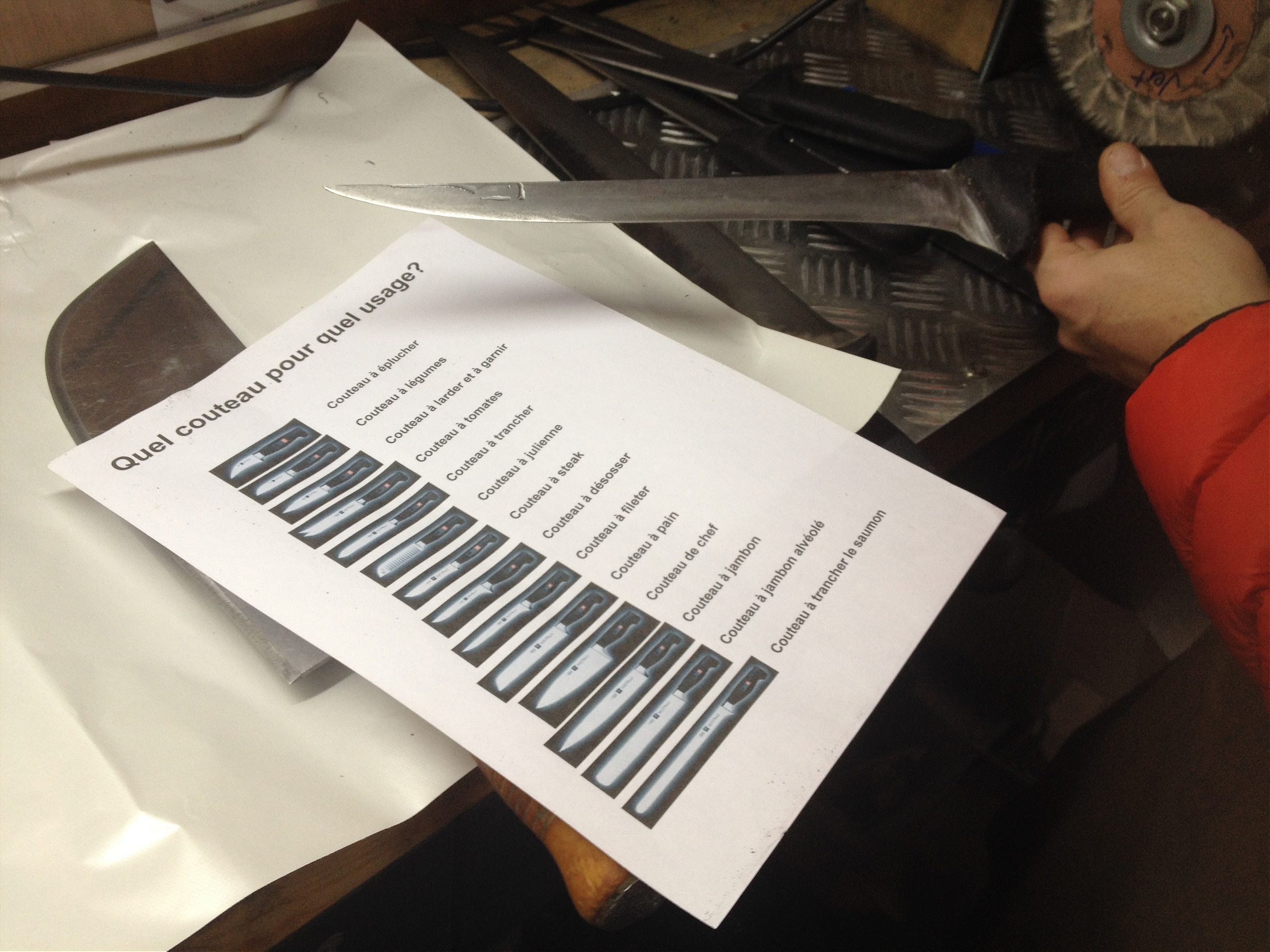

Titi, meanwhile, still has a cheat sheet in his truck, as he still considers himself a beginner. “It’s like when you just get your driving license. You don’t know how to drive yet.” He tries to make up for his relative lack of experience with humor and some goodwill gestures, like giving first time customers 20 percent off. Titi also adds a Band-Aid on the knives once he’s done reviving them. “It’s also a symbol to tell them, ‘Your knives really to cut now.’”

Individual knife grinders have different methods for deciding when the job is done. For Marius, it’s all about touch. He never works with gloves. “As more and more people rediscover the art of cooking with TV shows, a lot of people ask me advice about what type of knives they should buy. I just recommend that they pick them with their own hands. You should never choose them from catalogs or online.” Before returning the knives to their owners, Titi makes clear cuts on a sheet of paper.

Michel Vassout, a retired knife sharpener who used to be the only one in the southwest suburbs of Paris, still works the grindstone in a small shop near his home, sharpening garden tools. “I started this job when I was 15,” the 65-year-old says. After handing over his customer base to another knife sharpener, he became disillusioned. “People—even carpenters I used to work with—buy equipment they quickly throw away once they’re done with it.”

“This profession is not disappearing!” argues Henri Amblés, also known as Philogène GagnePetit on a blog about rémouleurs that he’s run since 2007. A former industrial draftsman and part-time volunteer in a cultural center, Amblés became fascinated with knife grinding when he produced a movie and a book about the subject more than thirty years ago. Now retired, Amblés fills his days buying everything related to knife sharpening. So far he’s amassed around 2,000 documents, mostly old pictures and posters and aggregating newspaper articles about new entrants. Henri Amblés has also written about Marius and Titi on his blog.

When Titi opened his business in September he gave himself a deadline of Christmas to determine whether or not this professional adventure was for the long run. Now that December has arrived, he’s not giving up. “I still don’t have a profit by the end of the month,” Titi says, “but it’s because I prefer buying new tools.”

As for Marius, he plans to open franchises in Lyon, Marseille, and Geneva where his daughter lives. He’s also regularly in touch with his former teacher, who is training a new generation of rémouleurs. “People now wait at least three months to get a spot in his class,” Marius says.