One of Japan’s leading whisky bloggers discusses the shortage of good Japanese single malts, the state of the country’s whisky industry, and how to order a highball.

Once upon a time, you could walk into a shop in Japan and buy whole casks of Yamazaki whisky from Suntory. Today, you’re lucky if you can get a bottle of 12-year old Yamazaki Single Malt. Earlier this year, a bottle of Yamazaki 50 became the most expensive bottle of Japanese whisky ever sold, after it was purchased at auction for about $299,000.

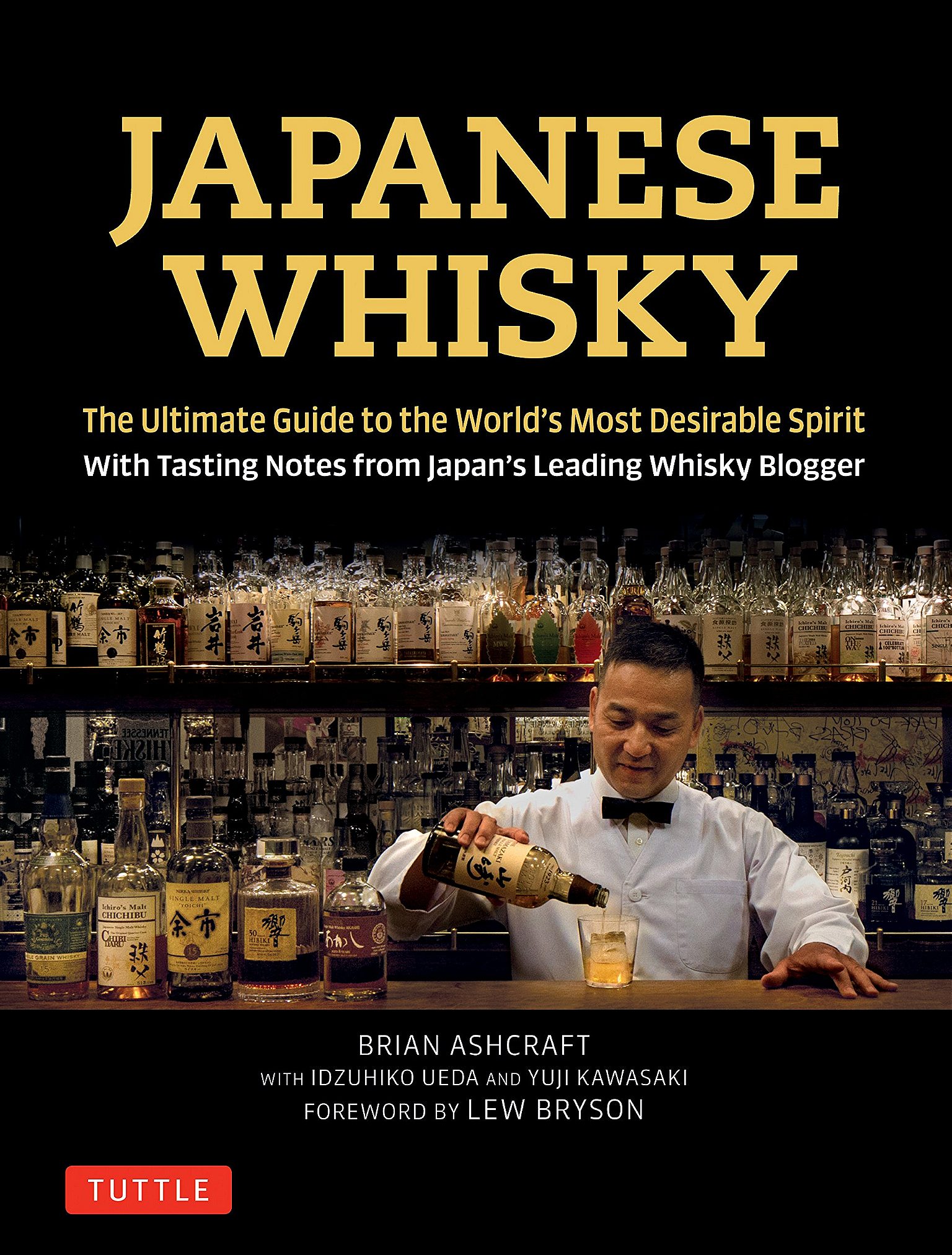

Brian Ashcraft has spent the past decade studying Japanese whisky. His new book, “Japanese Whisky: The Ultimate Guide to the World’s Most Desirable Spirit with Tasting Notes from Japan’s Leading Whisky Blogger,” explores how the spirit’s global popularity has exploded in recent years. Ashcraft, who is based in Osaka and has been living in Japan for 17 years, recently spoke to Roads & Kingdoms about the state of Japan’s whisky industry—and why it continues to become a popular spirit among whisky aficionados.

Roads & Kingdoms: It’s hard to find a good Japanese whisky in the market these days, unless you’re willing to pay an exorbitant amount. Can you explain this shortage?

Brian Ashcraft: The Japanese whisky market hit its peak in 1983, and then sales started to drop. People had been drinking brown spirits for decades, but clear spirits, like shochu, started to become more popular during the 1980s. The image of whisky in Japan was more of “Oh, that’s what my dad drinks.” Japanese brands like Suntory and Nikka weren’t selling as much whisky as before, so they started producing less.

But whisky sales started picking back up around 2006 when people began to rediscover the spirit. About two years later, Suntory did a brilliant job reintroducing the highball, a drink made of whisky and soda that has long had a following in Japan. That helped turn the ship around. People started buying a lot of Japanese whisky, but prices shot up because there was such a small amount of stock left over from the 1980s. Since then, prices have continued to rise. The upside is that Japanese whisky is finally getting the recognition that it deserves. The downside is that you can’t walk into a store and get certain bottles anymore.

[Read: Inside the hidden journals of a gay man in Tokyo]

R&K: Is there a chance that the shortage, and the increase in demand, could lead to a decline in quality?

BA: I don’t think that there’s going to be a decrease in quality for the really famous single malts or the premium blends. Whisky takes time. It needs time in wood to get those flavors. People see Japanese whisky as a super premium product. The best stuff that you can get in Japan is some of the best whisky in the entire world, and it often comes at a premium price. But there are other whiskies that are still widely available in Japan which are not as expensive.

R&K: Is there a downside to anything the Japanese whisky-makers are doing to compete in the current climate?

BA: Japan doesn’t require a minimum percentage of alcohol content in order to label a spirit as whisky. There are Japanese whiskies that are 37 percent alcohol by volume that just wouldn’t be considered whisky in the West. Because there aren’t strict regulations, what we’ve been seeing is stuff like a rice whisky being labeled whisky—but it’s really shochu.

I think within the Japanese whisky industry, people are being really creative in how they make whisky, but it also kind of opens the door for less scrupulous companies to come in. If the industry doesn’t technically define what Japanese whisky is, then people are going to buy something that’s not very good, and it would change their perception of Japanese whisky. The threat that’d bring to its prestige would be unfortunate, but hopefully the Japanese whisky industry can sort this out.

[Read: Can mezcal survive being popular?]

R&K: Where is Japanese whisky most popular outside of Japan?

BA: A lot of the really expensive, really rare whisky sold at auctions are purchased by buyers from other Asian countries. There’s also a lot of interest in Japanese whisky in America and Europe.

R&K: Are the Japanese doing whisky differently now? How has the country’s whisky production changed in recent years?

BA: There’s more creativity in how whisky is being made. For example, whisky makers are starting to embrace different types of wood. Traditionally, whisky is aged in oak. There’s American oak and European oak and those give different flavors to the whisky. There’s Japanese oak, and that brings out different flavors as well. Producers are now taking the lids from casks and then putting in lids made from different woods, like cherry blossom, chestnut, or apple. Experimenting with different kinds of woods in the cask gives the spirit a different nuance, a different flavor, a different feeling.

In the U.S. and in the U.K., there are very strict laws regarding whisky. Those laws don’t exist in Japan, which gives them a lot of flexibility in how they make their whisky.

R&K: Is there a point when you think Japanese whisky separated itself from Scottish whisky?

BA: I would say Japanese whisky, from the moment that it rolled out of the Yamazaki distillery in 1929, knew it was going to be Japanese. I don’t think producers looked at scotch and said “Okay, this is how you make it. Now we’re going to make it, but it will be Japanese.”

R&K: Is there a specific whisky you’re really missing out on right now?

BA: Oh man, the Hibiki 17. Hearing that Suntory was discontinuing the sale of Hibiki 17 made me kind of sad because that’s the one that I often recommend when people ask me for a good Japanese whisky that’s not over-the-top expensive.

R&K: In Hibiki’s absence, is there another whisky you’re really enjoying at the moment?

BA: One of the whiskies that I really like is the White Oak Akashi single malt. It’s not prohibitively expensive, and you can find it fairly easily. If I’m buying something to drink at home, I want to find stuff that is really good quality but not terribly expensive. I want something that doesn’t make me feel like I can only drink a certain amount of it on special occasions.

R&K: How do you order your whisky?

BA: If it’s summertime and I’m eating Osaka’s soul food, then I’ll order a highball. If I’m in a restaurant, I’ll order a proper highball in a glass, but if I’m at the supermarket and we’re going to make takoyaki at home, then I’ll just buy it in the can. Canned highballs are one of the great cheap drinking pleasures of Japan.

Read related stories: