Welcome to Mex-Tex.

Mexico is a big part of Texas, which makes sense, since Texas was once a big part of Mexico. By 2020, Hispanics are expected to outnumber Caucasians in the Lone Star State; in a place that prides itself on cultural independence, shifting demographics are seen by some as a threat to Texan state character. And yet Mexican cooking is more central to Texan culture than it is virtually anywhere else in the United States (with the possible exception of California). Even Texans who have never crossed the border have a favorite neighborhood Mexican restaurant, and local chefs incorporate Mexican flavors into everything, even the state’s most sacred meal: barbecue.

While most regional American barbecue styles center around pork, cattle is king in Texas, and beef brisket the most revered cut. But before Central Texas pitmasters began smoking the tough cut between the chuck and the shank in the late ‘50s, barbacoa—from which barbecue derived its name—held an important place in Texans’ hearts and stomachs. Mexican cooks would dig a pit in the ground—a pre-Hispanic technique practiced throughout Latin America—fill it with coals or hot stones, then cook a cow head overnight (throughout Mexico you’ll find lamb, mutton, goat or, in the Yucatán, pork cooked in a similar style). Safety regulations make that method near impossible in Texas today, with only one grandfathered restaurant in Brownsville carrying on the tradition, but a steamed version is now ubiquitous enough to be served at Chipotle.

The power of slow-smoked beef has won over Mexican eaters

I doubt that politics have dampened any good Texan’s desire for burritos or tacos (it certainly hasn’t in my hometown, Austin), but following the election I wondered if the current political climate might have cooled local enthusiasm for barbecue in Mexico City, where at least 10 Texas-style BBQ joints have opened in the last two years.

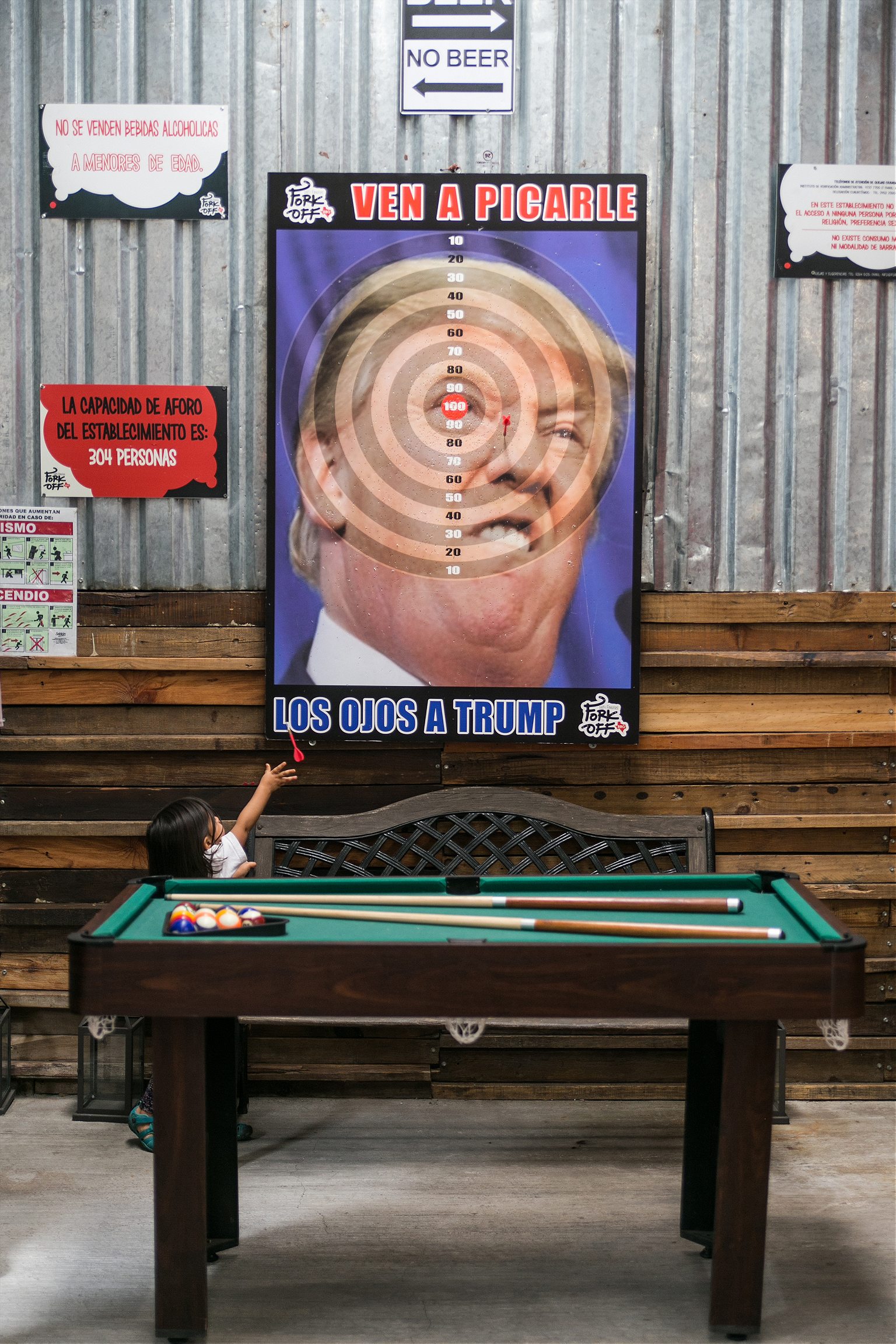

These Mex-Tex barbecue restaurants don’t shy away from American iconography, but they don’t ignore the political friction of this particular historical moment either. They fly the American flag, but aren’t afraid to hang a photo of Donald Trump as a dartboard. Despite this dissonance, the power of slow-smoked beef (combined with centuries of cultural exchange) has won over Mexican eaters, making for long lines and quick expansion plans for the most successful operations. But politics aside, the big question for a Texas barbecue snob (e.g. me) is whether the brisket is any good.

Any tourist who’s ever misjudged a traffic light while crossing the street in Mexico City will be familiar with the phrase pinche gringo—fucking gringo.

When directing my Uber driver to Pinche Gringo’s newly opened BBQ warehouse location in the Colonia Anahuac neighborhood, I type in the address instead of the name in order to avoid an embarrassing explanation of where exactly I’m going. A few minutes later we arrive on a street of low-slung brick and concrete buildings, the area’s industrial past a stark contrast to the luxury apartments just a few blocks away. The barbecue joint’s original location lies five miles to the southeast in Narvarte, a largely residential, middle-class neighborhood that’s also home to a clutch of the city’s best taquerías (they’re popular enough to have turned up in the New York Times Style Magazine). Though very different from one another, neither neighborhood is particularly popular as a destination for the city’s many American expats.

When I step out of the Uber in Anahuac, I’m greeted with a massive mural painted on the side of the building:

“Dear friends, together we are stronger. We support synergy, commitment, and understanding. We share our cultures and traditions. We demolish walls. We love Mexico, our beautiful country,” it says.

It’s not quite an apology (Texans aren’t known for saying sorry), but it is a kind of promise.

As it turns out, the mural wasn’t painted by a Texan, but by a New Yorker, Dan Defossey, who left his job at Apple five years ago to start the restaurant with Mexico City native Roberto Luna. “We partnered with an American political organization to show the debates,” Defossey says. “Then the day after the election, I wrote a love letter to Mexico explaining what we’re going to do now. We’re going to work together, cooperate, and prove that we’re better united than divided.”

The scale of the place reminds me of home. The cavernous room is large enough to host a 500-person rock concert and is furnished with the same reclaimed materials popular in trendy restaurants across the U.S. An American flag hangs near the entrance, striped with the bright colors of a Mexican serape.

Out back, three hulking offset smokers burn eucalyptus and oak around the clock for what some consider the city’s best brisket, as well as juicy links of jalapeño-cheddar and kielbasa sausages, tender pork ribs, and decadent pulled pork. One of the pitmasters, an American named James Weiting, rattles off scientific facts about barbecue smoke rings, a reaction between nitric oxide and myoglobin that gives brisket its characteristic, and much prized, pink stripe below the exterior, called the bark.

Brisket is unfamiliar to many Mexicans. Butchers, Defossey tells me, don’t have a translation for the word; they refer to it as the pecho—or chest—of the cow.

“Mexicans sometimes think American food is all burgers, hot dogs, and French fries,” Defossey says. “I can’t tell you how many people have asked why we don’t have French fries. Well, why don’t you have crispy tacos? Because that’s not part of the culture.”

Some other barbecue restaurants in the city incorporate Mexican flavors, but Pinche keeps the food authentically Texan. You won’t find tortillas, jalapeños (except in those sausages), or limes, and they discourage customers from adding sauces. The gamble has worked. Some 99 percent of their customers, they boast, are Mexican, a contrast to other barbecue joints located in neighborhoods populated by more Americans.

Still, they’ve had to make adaptations. To adjust for the higher elevation and drier climate, they smoke longer and moisten the meat throughout the cook. The meat itself also makes different demands. Traditionally Mexican cattle eat more grass than grain, but even their grain-finished cattle has a leaner fat cap. To deal with the realities of operating in a dense neighborhood, they’ve had to instal smoke-scrubbing charcoal filters to minimize the smell, a common complaint amongst Austin neighborhood associations (who were silenced by protests from pitmasters like Aaron Franklin).

When it’s finally time to eat, I walk down a counter-service line just like in Texas. A Mexican man expertly cuts thick slices of brisket, grabs a jalapeño-cheddar link straight from the smoker, and drizzles queso onto a pulled pork sandwich.

Once you’ve been around enough brisket, you can almost taste it with your eyes. The bark reveals itself as either a crackly pepper crust or a limp black shell. The juices either soak the meat like water on a white T-shirt or leave it looking shriveled and gray. Even the way the brisket sags in the gloved hands of a pitmaster hints at the quality.

It’s hard to impress a spoiled Texan, especially one who lives four blocks from Texas Monthly’s #2 and #8 best barbecue joints (Franklin and Micklethwait, respectively), but Pinche Gringo isn’t bad at all. The texture is tougher than I’d like and not as fatty, but the smoke flavor is nuanced, not overbearing, and a subtle bark complements the firm texture.

If you turn up at one of Porco Rosso’s seven locations at noon, you’ll see a crowd of American expats. Come closer to three and most everyone is speaking Spanish.

Mexicans eat lunch later than Americans, just one of the cultural differences that’s served as a challenge and opportunity for Porco Rosso. Many Mexicans still associate barbecue with Tony Roma’s soggy ribs or McDonalds dipping sauce, but co-owners Bobby Craig and Pedro Ochoa know the real deal. Both were born and raised in Mexico City, but Craig grew up visiting his father in Kansas City and toured the state’s legendary barbecue joints as a child. Ochoa spent years living in New York City around the corner from Dinosaur Barbecue and was a regular at Mighty Quinn’s and Fette Sau.

They know American barbecue intimately, but unlike Pinche Gringo, Porco Rosso doesn’t aim to copy their favorite versions from up north. As we sit at a picnic table under the shaded canopy of their Roma Norte location sharing Mexican craft lagers, Ochoa and Craig explain to me their philosophy of incorporating local flavors.

“Most people doing barbecue in Mexico are trying to replicate what’s over there. We respect the tradition and institution of barbecue, but then again, if no one has tried it before, you can mix in different flavors,” says Ochoa.

That means adding powdered guajillo, cayenne pepper, and smoked paprika to their rubs and spiking their mac and cheese with chipotle. The cole slaw has a sesame-soy base instead of mayonnaise for a tropical touch from the Pacific state of Sinaloa (famous for its ceviche in Mexico and its eponymous cartel everywhere else). One of Porco Rosso’s most popular dishes is basically a brisket taco with a fried exterior of mozzarella cheese. The hip clientele demands vegetarian and vegan options, too, so Craig and Ochoa offer smoked cauliflower and roasted broccoli. The Roma location even boasts an underground pit for cooking barbacoa, though they haven’t managed to use it since the neighbors complained about the smell (some problems are universal).

Before Porco Rosso opened, the empty corner lot was full of trash and squatters, a gritty relic of the 90s and early 2000s in the now heavily gentrified Colonia Roma. The owners struck a tenuous agreement with the landlord, who granted them use of the space but not the right to build a permanent structure. Instead, they cook in a 40-foot shipping container set at a right angle to a shorter, 20-foot container, used for the bathrooms and storage. In the open space between them, customers sit at wooden picnic tables amidst vegetable patches, snaking vines, and planters sprouting chard, lettuce, spearmint, rosemary, and oregano.

When a plate of food finally arrives, it looks like it’ll score big Instagram likes. The meat glistens with fat. Purposeful streaks of sauce criss-cross it like grill marks. Sides and pickles add splashes of color. The meat arrives fanned out on wax paper, not quite the brown butcher paper common in Texas restaurants, but close enough.

On a previous trip to Mexico City I’d eaten at Porco Rosso’s Condesa location, so I knew what to expect. The brisket tastes like it’s from a mid-tier Texan joint, with fat that hasn’t quite rendered. A thick layer of sweet and smoky sauce, mopped on liberally toward the end of the smoking process and again prior to serving, masks the toughness of the meat. Chile heat plays nicely off a base of sugar and cumin. It’s closer to Kansas than Texas, but with a sweet, earthy undercurrent that’s entirely Mexican. Another Kansan staple, the crusty leftover “burnt ends” of the brisket’s fatty side, only developed a following once Ochoa and Craig started serving them as an American-style burrito with cheddar cheese, avocado, lettuce, beans, sour cream, and pickled chiles.

If I were living in Mexico and craving brisket, this would hit the spot, which is more or less how Porco Rosso first developed a following two years ago. American expats, who live mostly in the same neighborhoods where Porco Rosso first set up shop, flock there daily. The American embassy hires them for catering. Just as Americans take note if a new Szechuan restaurant is full of Chinese people, Mexicans saw the long lines of gringos and followed.

I don’t typically patronize restaurants with puns in their names, but I make an exception for Fork Off since they took the trouble to incorporate the outline of Texas into their logo.

After that and the flag, the most iconic state symbol might be the red-and-white Lone Star Beer badge, and though Fork Off doesn’t serve my favorite watery American lager, they do keep the sign hanging on their corrugated metal wall alongside the typical array of country dive kitsch, like cow hides and wagon wheels. One decoration you probably wouldn’t see back in Texas is a large image of Donald Trump’s face used for a dart board.

Owner Cesar Romero greets me wearing a collared Southern Pride work shirt. Founded in 1976 in Decatur, Illinois, Southern Pride is the barbecue industry’s most well-known manufacturer of automated “set it and forget it” smokers, which have a divisive reputation in the industry as either a savior or a crutch.

In addition to managing the restaurant, Romero works as a distributor of Southern Pride smokers. Since he’s in the importing business, NAFTA is a big concern. When I ask how local customers have reacted to the restaurant, he shrugs off the differences between the two countries as political, not personal. People here seem upset at America, but not at Americans.

“I think people let politics aside. We’re friends. When you speak with people, there isn’t a problem. Here in Mexico, when foreigners come to our country, the majority of people try to help,” says Romero.

During my visit, the Texas government was busy passing a law outlawing sanctuary cities. It surprised me how many Mexicans not only knew about the pending Senate bill, but called it by it’s abbreviation, SB4.

“The governor of Texas is asking all the police to ask Mexicans for documentation, so now many people who used to travel to Texas, they’re thinking about not traveling. California, Florida, other places, too,” says Romero.

That hesitation doesn’t extend to consuming American culture on the safe side of the Rio Grande. A small queue has formed of customers hungry for pulled pork, baby back ribs, and the star of the show, Texas brisket. When they first opened, Cesar tells me, they cut the meat to order in front of the customers, but later found that Mexicans prefered to order at the counter, then have the meat brought to their table. It’s a subtle difference, but speaks to different attitudes toward restaurant experiences.

Most Mexican food, he says, is served straight from a grill, so customers were initially confused when the meat arrived less than screaming hot. Mexican cooking also tends to favor super tender, braised meats, making lean brisket a tougher sell. People here, he tells me, will also take any opportunity to make a dish spicier, as evidenced by a nearly empty bottle of hot sauce on the table.

Romero shows me the pile of mesquite logs used to smoke the brisket for 14 hours. I’m inspired by his story about discovering barbecue on a family trip to San Antonio and impressed by the gumption it takes to introduce a city to a new culinary experience.

But the brisket is not for me. To accommodate what he describes as Mexico’s penchant for tender meat, he cooks his brisket into a spongy pot roast with a texture more akin to a Passover brisket than Texan one. The meat had its thick pink smoke ring, but the acrid flavor of the mesquite was nearly as harsh as liquid smoke.

On my way out I take some photos of Romero in front of a world map pinned with visitors’ home towns. A similar map hangs in the back room of the legendary Louie Mueller Barbecue in Taylor, Texas. Clearly the Romeros feel proud to share Texas food with the rest of the world, and no matter how much flavor is lost in translation, it’s hard not to root for them.

The Trump dartboard hangs right next to the world map, and as I wrap up my visit, a small girl walks up and grabs a magnetic dart. She hurls it at the wall, but doesn’t reach the bullseye framed around Trump’s orange forehead. It sticks just below his slack-jawed chin. A few seconds later her mother appears and walks her over to a plate of brisket. It may well be her first taste of Texas. I hope it won’t be her last.