Horse meat is outlawed in several American states. But up in Canada, they’re so hungry they…

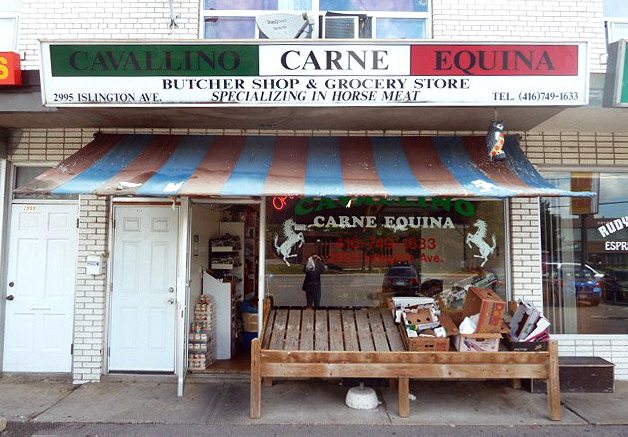

Cavallino Carne Equina & Groceries is sandwiched between a jewelry store and a members-only Italian social club in a fraying strip mall in North York, Ontario. It’s a bleak patch of suburbia about 30 minutes west of Toronto, not far from where late ex-Mayor Rob Ford lived and smoked crack in his sister’s basement.

Big, block letters on the store’s sign read, “SPECIALIZING IN HORSE MEAT,” and the plate glass window out front is decorated with two rearing stallions in silhouette. When I visited not long ago, an old butcher wearing a blue baseball cap that said “Toronto” across the front sat on a milk crate by the door, working a scratch-off lottery ticket.

The store was dark and empty, and I thought at first they might be closed. An unenthused woman of roughly the same vintage as the man on the crate sat inside, watching Italian TV.

She turned toward me with obvious displeasure. Oh, for Christ’s sake, her body language sighed.

“Hi,” I said, “do you have hor—”

“Leo!” the woman bellowed toward the guy on the crate, who slowly hoisted himself to his feet and began making his way inside.

She turned to me. “The butcher is coming,” she said with a thin smile before going back to her program.

Many American zoos feed horse meat to their carnivorous animals, but buying or selling horse meat for human consumption is a crime in several US states, including Florida, Texas, and Illinois. In California, where bestiality is just a misdemeanor, simply owning a horse with the intention of eventually eating it can result in felony charges.

In Canada, however, eating horse is perfectly legal. Four plants—two in Alberta, two in Quebec—disassemble horses into cuts of meat. While horse meat is commonly found in the French-speaking parts of Canada, it is not often seen in the Anglophone provinces. Until last year, I had eaten horse three times in my life, all unintentional: once in Berlin, where I unknowingly had lunch at a wurst stall evidently famous among locals for horse meat sausage; another time in Rome, when a translation error led to my enjoying the most delicious “pork” mortadella I ever tasted; and a third in Amsterdam, when a friend took me to a cozy spot that served only horse, which he let me believe was beef until after we left.

On a recent trip to Toronto, I got to talking with Darcy McDonell, the proprietor of a restaurant called the Farmhouse Tavern, not far from the city’s stockyards. At one time, the restaurant offered horse meat poutine, but McDonell said he dropped it after the objections from customers became overwhelming. I was curious about the fuss, and wondered what horse meat would taste like if I actually knew I was eating it.

There are a handful of fancy restaurants in the city that serve horse, and prices are relatively high. The Black Hoof, a Toronto “nose-to-tail” pioneer, serves horse tartare, for $17 CAD (about $13 USD). La Palette, a French bistro in Toronto’s Queen West neighborhood, serves a $35 ($27) horse steak. A downtown spot called Buca, which serves cured horse meat as part of a salumi plate running $18-$28 ($14-$21), turned down my request for an interview and a tasting. I stopped into every meat market I could find, looking for horse, but no one seemed to have it. After a friendly butcher told me about Cavallino Carne Equina & Groceries, I went with Plan D.

I was reminded of a gristly piece of low-grade tuna

As a place supposedly specializing in the stuff, I was expecting a pristine display case filled with expertly butchered horse steaks and chops, but the case was empty. Leo the butcher said he was out of sirloins, strip steaks, fillets, roasts—everything but tenderloin, actually. I nodded, and he disappeared into the back, returning moments later carrying a large block of horse tenderloin. The edges were rough and sinewy, and I was reminded of a gristly piece of low-grade tuna one might see at a cheap sushi bar.

Leo had a brushy mustache, wild eyebrows, and zero desire to talk or make eye contact. It felt a bit like I had somehow wandered into the home of strangers who weren’t quite comfortable asking me to leave.

“How much you want?” Leo barked, holding the edge of the knife to the flesh at different intervals, the way a cheesemonger might.

While buying horse meat in the armpit of Ontario had once seemed like a semi-interesting way to kill a couple of hours, the idea of eating it was now beginning to turn my stomach. For better or worse, societal norms are powerful influencers, I’ve been duly conditioned to view horses as, well, not food.

“About like this,” I lied, holding my index finger and thumb about a half-inch apart. “Two of them, please.”

As I tried to make out what the blurry green tattoos on Leo’s forearms might have once depicted, I thought about how hippophagy—the eating of horses, denounced by the church as a symbol of Celtic and Teutonic paganism—was outlawed by Pope Gregory III in the year 723. A “filthy and abominable practice,” he called it, though some historians maintain the real motive was the church’s desire to to keep horses alive for use on the battlefield.

Leo sliced cleanly through the glistening horseflesh, framed portraits of various Catholic saints hanging on the wall behind him.

Despite Papal objections, horses are still commonly eaten around the world. One can find horse meat bresaola in Italy, a traditionally Catholic country. It is made into satay in Indonesia, sausages in Kazakhstan, and eaten raw in Japan. Horse meat can be found on restaurant menus in Belgium and France, and a traditional Rhineland sauerbraten is made not with beef, but horse meat.

Still, horses have never been bred for the quality of their meat, but for their physical abilities. And since horses are not raised specifically for eating in all but a few countries, aligning supply with demand means slaughtering lame, sick, or old animals that have outlived their usefulness to their owners.

Prices charged by trendy restaurateurs notwithstanding, old thoroughbreds can go for as little as $100 to so-called “kill buyers,” who hang out at racetrack auctions and bid on horses past their prime. In fact, thoroughbreds No Day Off, Deputy Broad, and Beau Jacques ended up at the Viande Richelieu processing plant in Montreal. I tried to engage Leo, inquiring about the meat’s provenance, something I imagined he’d be proud to discuss. He wasn’t. After an awkward silence, the woman—Leo’s wife Filomena, it turned out—looked away from the TV long enough to tell me that the drugs regularly administered to racehorses during their careers “make the meat no good.”

To keep consumers safe from drug residues, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) says it regularly tests horse meat for phenylbutazone, an anti-inflammatory commonly given to racehorses, and that results show a “very high compliance rate.” As stipulated by the Meat Hygiene Manual of Procedures, any horse arriving at a slaughterhouse must have a so-called Equine Information Document, which lists all vaccinations and medications it received over the previous six months.

Otherwise, horse meat is quite healthy. It contains 25 percent less fat, 30 percent less cholesterol, and almost 30 percent less sodium than beef, although eating raw or undercooked horse meat can lead to trichinellosis, a parasitic disease that causes nausea, diarrhea, chills, vomiting, and sometimes, death.

Horses are ungulates, from the same clade of hoofed mammals as deer and elk. Yet, the idea of eating horses tends to upset people far more than the eating of many of their relatives. La Palette has been the focus of pickets by animal rights activists, and chef Peter McAndrews abandoned a plan to serve horse meat at one of his Philadelphia restaurants a few years ago after receiving multiple death threats over it.

However, Dr. Terry Whiting, chief veterinarian for the Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Development agency, has argued that, “Of possible farm animals available for human food, it could be argued that horses have, on average, the best quality of life and, therefore, should provide the fewest ethical issues for an individual that normally would prefer free range eggs, grass fed beef, and similar products.”

In an email, Whiting told me that he further takes issue with the notion that eating horse meat could ever be illegal. Laws are written to protect people from harm, and “there is no physical injury to persons or the horse by the eating of horse meat.”

“Horse meat created under food safety regulation is both safe and nutritious for human consumption,” Whiting said. “The horse is dead, and dead is not some bad way of being alive. Dead is the loss of existence.”

As Leo wrapped my two slices of horse tenderloin in brown butcher paper, I felt a twinge of buyer’s remorse before I had even bought anything. In France, horse costs $20 a kilo, second only to veal in price, and I feared taking a big hit at the register for something I no longer wanted to eat. Leo tossed the meat on a scale, then grunted something at Filomena, who relayed the message to me.

“Three dollars,” she said.

“For both?” I asked, figuring there must have been some kind of mistake.

“Horse, it’s cheap,” Leo offered with a shrug.

That evening, I gave the meat to my buddy Cam, who seasoned it with a little sea salt and coarsely-ground black pepper, then grilled it on his patio.

He said it tasted just like beef.

Cover illustration by Sean Moxley.