A portrait of the megacity of Chongqing in southwest China, where millions are witnessing unprecedented urbanization and having to adapt to new worlds.

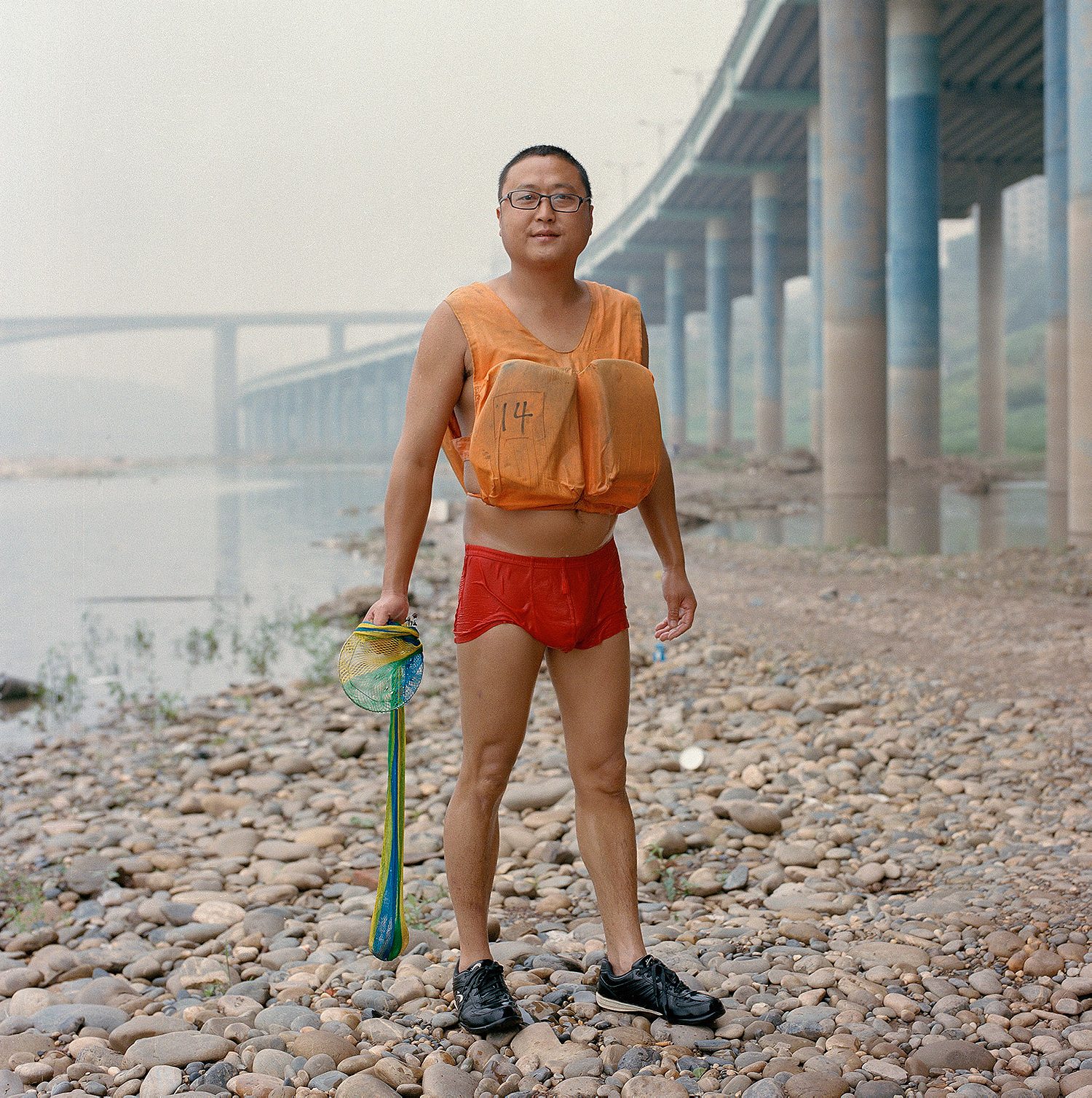

There is the farmer whose land was taken by the government but who continues to cultivate a small mound of dirt between the skyscrapers. There is the young woman who travels from the outskirts of the city with her baby to look at the new luxury shops and cafés she can’t afford, a proud smile on her face. There’s the masseur in the old quarter, who waits for his historic neighborhood to be destroyed and to be moved into a new tower apartment, where he’ll continue his business. In the mega-city of Chongqing, in southwest China, there are millions of stories like these, of people witnessing massive urbanization and of adapting to new worlds. Shanghai-based photographer Tim Franco met some of them during the five years he spent documenting Chongqing. His first book, “Metamorpolis,” is a portrait of the relatively unknown yet booming city. He spoke to R&K from Shanghai.

Roads & Kingdoms: What first brought you to Chongqing?

Tim Franco: In 2009 I wanted to discover lesser-known cities in China that were urbanizing rapidly. Cities that I had heard of but that I had never really visited. I went to Wuhan, Chengdu and Chongqing. As soon as I arrived in Chongqing, I fell in love. It’s a city that’s completely out of the ordinary, not only because it’s urbanizing rapidly but also because it’s stuck between rivers and mountains. You really feel like you’re in a movie as soon as you arrive downtown. It’s overwhelming for the senses, it’s pretty incredible. I stayed a week, walked around and took pictures everywhere. At the time I was working with the Enrico Navarra gallery on an architecture book called “Made By Chinese.” It was a big project that lasted almost two years and that took me across China, and inevitably to Chongqing. The more I learned about this city, the more I was convinced I should do a project over there. I started shooting in medium format on my third visit. I went regularly, sometimes as often as once a month. I liked not living there because I get bored easily. For example, I haven’t really done an interesting project in Shanghai since my first year there. But every time I returned to Chongqing, I was amazed. And on top of that, there were always huge changes between each visit and that was unbelievable.

R&K: You had already been living in China for four years before you stepped foot in Chongqing, yet it sounds like you were still bewildered.

Franco: Yes. There are no cities like it. I had a similar feeling when I first went to New York as a child. There are cities in the world that are just very unique. I’m interested in these kinds of environments, which really exist in three dimensions.

R&K: What exactly is happening in Chongqing?

Franco: This is the story of China in general, seen through one city. All the phenomena that are taking place in Chongqing exist elsewhere in the country, but they’re just 10 times more visual and quick and present there. Looking at Chongqing enabled me to document all the things about China that I wanted to talk about, all the things that I felt living there and that I tried to explain to people when I was going back to France or to the U.S. In one photo of Chongqing, you understand immediately that what’s happening is pretty insane. I liked that. I knew I had found a place that brought all these things together.

R&K: What angles did you use to document this massive city?

Franco: The first times I went, I concentrated on the unbelievable contrast between mass urbanization—these buildings that suddenly grew out of the ground in a chaotic and grey way—and the old city that dates back to the time when Chongqing was the capital of China. It’s a contrast I had observed in Shanghai, but here, it was like it had been compressed in one dense neighborhood. Some people say Chongqing is the most populous city in the world with 36 million inhabitants, but that’s not correct. Chongqing is a municipality. There are only about six million people who live in the city. The government is trying to urbanize the remaining population. At the time of the Three Gorges Dam project, many people were moved to the city, which the government wants to turn into the capital of central China.

R&K: So these people are the new inhabitants of Chongqing?

Franco: Yes, it’s this rural population. In China, there’s a system called Hukou, which basically refers to ID cards. There are two types: urban and rural. In Chongqing, the government is trying to transfer the rural Hukous to urban Hukous. The problem is that a lot of farmers find themselves in this huge city and they don’t know what to do. These are families that have lived in the countryside for generations and who are told one day: we’re taking your land, here’s an apartment, now you have to become a city person. The younger generations manage, because in China people are so resilient. They’ll work as taxi drivers or things like that. But the older generations, it’s hard for them to picture working in an office. So they just end up doing the only thing they know: work the land. That explains the amazing landscapes, where in the middle of the city you’ll see people with goats, using every bit of land imaginable for agriculture. It’s really impressive.

R&K: That’s one surprising thing in your photographs: you manage to always have a bit of nature in each of them.

Franco: It wasn’t really a choice I made, it’s just the reality of Chongqing. Despite the urbanization, people are trying to keep a link with nature. In addition, as I explained, Chongqing is not just a city. There are still many parts of the municipality that look like the countryside, though some will have a huge skyscraper in the middle of a farm. So yes, nature is part of the urbanization story of China too.

R&K: Do locals realize the extreme nature of this urbanization?

Franco: Chinese people are often quite proud. There is something called the “Face” concept in China, which basically means showing the good sides of things and closing your eyes on the rest. So as long as the development process is evolving and that Louis Vuitton stores are popping up downtown, well, even if some people are completely ostracized and their lives are hard, overall the country is going in the right direction. In the meantime, those who are at the very bottom won’t hesitate to say that it isn’t possible to continue this way. Some families I spoke to said the transition was impossible. The government is all about policies to urbanize the people, but they don’t do much else than give them an apartment. There’s no education or training process. You just have to get by.

R&K: Why does the government want to urbanize all of these people?

Franco: To become a developed country, China wants to get rid of this rural population and go from this primary sector to the secondary and tertiary sectors. This is the big picture. China always has the big picture in mind, but how to get there is a different story. The worst part is that they are kind of successful at it. They step on people without looking at the damage caused, but it actually works. It’s crazy. In Chongqing, the first time I went, it was hard to get a good coffee in the morning. Today there’s everything: H&M, Uniqlo, big hotel chains, an Apple store just opened. All of this happened in five years. Last week I took a photo from the roof of the Westin hotel, where you can see that the entire peninsula is full of skyscrapers. There were none of these towers the first time I was there.

R&K: You spoke about the old houses built in the 1920s and 30s that you saw the first time you went to Chongqing. Are some of them still present today, and is anyone trying to preserve them?

Franco: You see less and less of them. There were two old cities that were pretty well known. A neighborhood called Shibati, which means “18 steps,” was particularly beautiful it was full of small streets that went from the hills to the river and it used to be full of brick houses. The other one, under the cable car route, was similar. These are neighborhoods I went to a lot, and I spoke to many people there. I don’t think I met one person who said: yes, it’s a bit sad that they’re destroying the old houses. These old houses, they’re not well maintained, the conditions are pretty grim. Between that and living in modern accommodations, they don’t hesitate. It’s a definite step up for them, so I didn’t find many people who regret these old buildings. This year, when I went back to Chongqing, the two neighborhoods were completely gone.

R&K: Why isn’t Chongqing more famous?

Franco: There’s no reason for it to be famous, really. There are other large cities like this one in China. I guess there is a recent push by Xi Jinping who wants to create a new Silk Road to develop these large cities in central China, but that’s a fairly new thing. I actually thought that people would pay more attention to Chongqing after the Bo Xilai saga – I hope that someone will make a movie about what happened in this city between 2010 and 2015, because it’s crazy. You have the mafia, the murders, the corrupt politicians… And that’s only the tip of the iceberg. It’s definitely a city that deserves to be known.

“Metamorpolis”, by Tim Franco, published by Pendant ce temps, is available here for pre-orders for €29 until April 17th and €39 afterwards.