Selling Escobar: Is it immoral to build a tourism industry around the king of Cocaine?

MEDELLIN, Colombia—

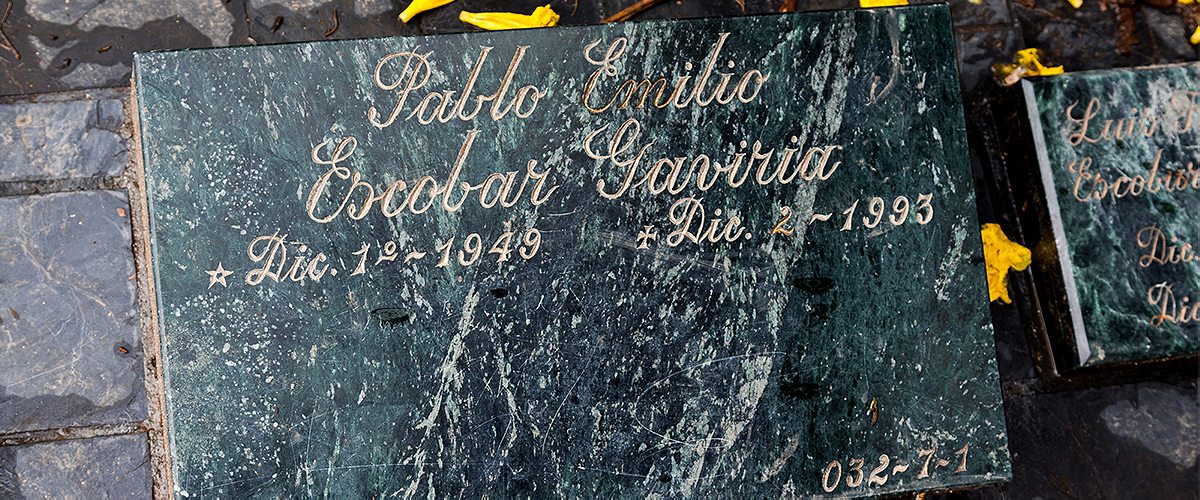

On December 2, 1993, one day after his 44th birthday, Pablo Escobar died on the roof of a modest home during a police raid in what is now an otherwise unremarkable middle class suburb of Medellin, Colombia. Twenty years later, the man who invented modern-day narco terrorism and brought his country to the brink of ruin still inspires extreme emotions. Colombians either love him (if you’re from one of the many poor barrios where he built homes, schools, and soccer fields) or hate him (if you’re one of the tens of thousands who lost loved ones during Escobar’s years of violence).

Colombians can agree on one thing, however: Escobar sells, especially to the growing number of tourists visiting this South American country. As Colombia gropes its way out of the shadows of decades of violence, nationwide tourism is on the rise—up 300 percent since 2006. Tourism officials predict a record-setting 2 million people will visit Colombia in 2013. The following year they’re aiming for twice that.

The irony of this welcome increase in visitors, however, is that there is a corresponding rise in the kind of tourism that Medellin officials really wish you would avoid: Escobar tours. The visitor’s bureau refuses to promote them—a top administrator said she “feared” reinforcing the Colombia-cocaine stereotype and even some tour companies like Colombian Getaways decline to offer them, calling the idea “hurtful.”

And yet the drug lord’s legacy is unavoidable. At the height of his power in the 1980s and early 1990s, Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria controlled 80 percent of the cocaine traffic to the United States. He had enough money to offer to pay Colombia’s national debt. He briefly held a seat in Colombia’s Congress. His crimes included assassinations, car bombings, extortion, and the bombing of an Avianca commercial flight. Escobar’s brother, who was the cartel’s accountant, claims that the group spent $2,500 on rubber bands each month for wrapping the bundles of cash. In 1987, Escobar appeared on the inaugural Forbes magazine list of billionaires, and he remained on that list until the day he died.

Now there are at least 10 companies offering Escobar tours of Medellin—including his grave, the site where he was killed, and other grisly landmarks. My guide on the $45 Escobar Tour offered by Medellin City Tours, John Echeverry, says he had to think long and hard before agreeing to take the job. As we turn our backs on Escobar’s (surprisingly restrained) grave, Echeverry John tells a story about the time that he and 44 of his classmates (including the son of Escobar’s cousin and Medellin Cartel business manager Gustavo Gaviria) were invited to Escobar’s private retreat, Hacienda Napoles, for the weekend.

THE MEMORY OF THAT EXPERIENCE HAS HIM CAUGHT BETWEEN ESCOBAR EXCITEMENT AND ESCOBAR SHAME

“There were mini motorcycles for all of us,” Echeverry remembers. “We sat at a long table and we could have whatever we wanted.” He shakes his head. The memory has him caught, like the rest of the country, between Escobar excitement and Escobar shame. “There were no limits. It was like Disneyland.”

It is perhaps fitting, then, that the Colombian government handed the 3,000-acre estate, located about four hours from Medellin, over to a management company that turned it into the largest theme park in South America. It is called Parque Tematico Hacienda Napoles (Hacienda Napoles Theme Park), and advertises itself as a destination “for family tourism, environmental protection and the protection of animal species in danger of extinction.” Since it opened in 2008, managers say it has attracted about one million visitors, overwhelmingly Colombian, who pay up to $30 to get a peek.

But the managers took care not to turn the drug lord’s ranch/zoo/airport/headquarters into a monument to the narco lifestyle. The drug-running plane that Escobar had perched atop the Hacienda Napoles entrance was painted with friendly zebra stripes. Five new theme hotels were built (Africa, Casablanca, etc). Escobar’s private bull ring was recently turned into the Africa Museum. A 30 foot tall fake octopus now douses shrieking swimmers in a water park that is as tacky as a Florida putt-putt course. Escobar’s original menagerie of wild animals—which included 4 hippos—has been expanded to include lions, tigers, rhinos, jaguars, and more than 40 hippos. A pair of elephants will arrive as soon as the paperwork is sorted out.

Although Hacienda Napoles staff say they are discouraged from answering any questions about the previous owner, when I visited on a excursion organized by Palenque Tours (a company owned by two political scientists), we did make a stop at the one place on the property where his legacy is at least mentioned: the ruins of Escobar’s personal home. Ravaged by shovel-wielding locals looking for riches allegedly buried under the pool and in the walls, its gutted rooms have been turned into the Memorial Museum, which presents a grisly timeline of Escobar’s life, rampage, and death.

Colombians don’t need to take the trip to his former estate to confront Escobar’s legacy; his life story is a made-for-TV drama. Pablo Escobar: Boss of Evil, is the most ambitious production ever undertaken by Caracol TV, with more than 70 episodes involving 450 locations and 1,300 actors at an average cost of $160,000 per episode. The series is remarkably personal for its creators who each have painful connections to his crimes. The show’s writer and producer, Juana Uribe, is the daughter of journalist Maruja Pachón, who was kidnapped by Escobar. Uribe’s uncle was former presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán, who was murdered by the cartel. The series co-producer is Camilo Cano, whose father was a newspaperman who was also slain by the cartel.

More than 11 million viewers—nearly a quarter of Colombia’s total population—tuned into the debut of the series. The series producers say their aim has been to set down the full facts of the Escobar era in one place. Each episode begins with the warning: “Those who ignore his story are condemned to repeat it.”

It is possible, however, to take Escobar commerce too far. Escobar’s son, who fled to Argentina with his mother and sister and is now an architect living under the name Sebastián Marroquín, recently filed a petition to trademark his father’s name, passport image, and other official documents to be used as graphics on his Escobar Hanao line of $170 jeans and $95 T-shirts. (The clothing company’s tag line is “In Peace We Trust.”) Marroquín has said that the clothes are intended to be “an auto criticism of my father’s history, and an invitation for the youth to be conscious of the dangers of entering the drug and drug trafficking world.” Colombia’s Superintendent of Industry and Commerce denied his trademark petition, arguing that granting the permission could “disrupt public order.”

In an interview at an upscale Medellin restaurant, Escobar’s sister, Luz Maria Escobar Gaviria, says she has nothing against making a profit off her family’s name. She is currently finishing a book about her brother and is considering opening an Escobar Museum in Medellin. Still, she agrees that selling the Escobar legacy doesn’t help Colombians move out from under the shadow of her brother, whom she admits “was no saint.” LuzMa, as she’s commonly called, says she wants to see a South Africa-style Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Colombia, but until that happens, she is making her own gesture: leaving hand-written apologies on the graves of her brother’s known victims.

Medellin-born artist Fernando Botero, famous for his enormous bronze sculptures of bulbous animals and naked people, has his own complicated history with Escobar. The artist reluctantly admits that the drug lord owned some of his paintings (a fact he considers “repugnant”) and drug violence has also been a theme of Botero’s work, including his pair of paintings Killing Escobar which depicts the drug lord’s ignoble roof top death.

These days Botero, who is 81, is ready for fresh inspiration. “I want to paint peace in my lifetime,” the artist says. “I try to remember the Colombia that I knew when I was a young man. The good Colombia.”

Lately he’s become more optimistic that Colombia can become the country he craves, and concedes that selling Escobar can be part of that process if it keeps Colombians from forgetting. “Part of the story of every country is dark,” Botero muses. “In America, you have Al Capone. Someone has the idea to charge money to see where Escobar died? I do not argue with that. We can’t forget completely.”