Acclaimed photographer Newsha Tavakolian talks to Roads & Kingdoms about her new exhibition in Tehran.

When I first met her, the photographer was singing. It was at a late-night afterparty for the Tbilisi Photo Festival, on the hillside patio of mutual friends. While everyone else quietly drank their Kakheti wine and coughed their smokers’ coughs, Newsha Tavakolian sat at the table and belted out a Persian love song, clear and strong and more than a little mournful.

Tavakolian is one of Iran’s most acclaimed young photographers, a finalist for Magnum’s Inge Morath award who has exhibited around the world and worked for everyone from Time Magazine to Le Figaro to National Geographic. Her work moves from journalism to art and back again, but always it carries a bit of that mournful singing with it. This is especially true of her latest exhibition, LOOK, which opened December 14 at Aaran Gallery in Tehran. I caught up with her recently by Skype to talk about art, sanctions and censorship.

Roads & Kingdoms: Tell me a bit about the exhibition.

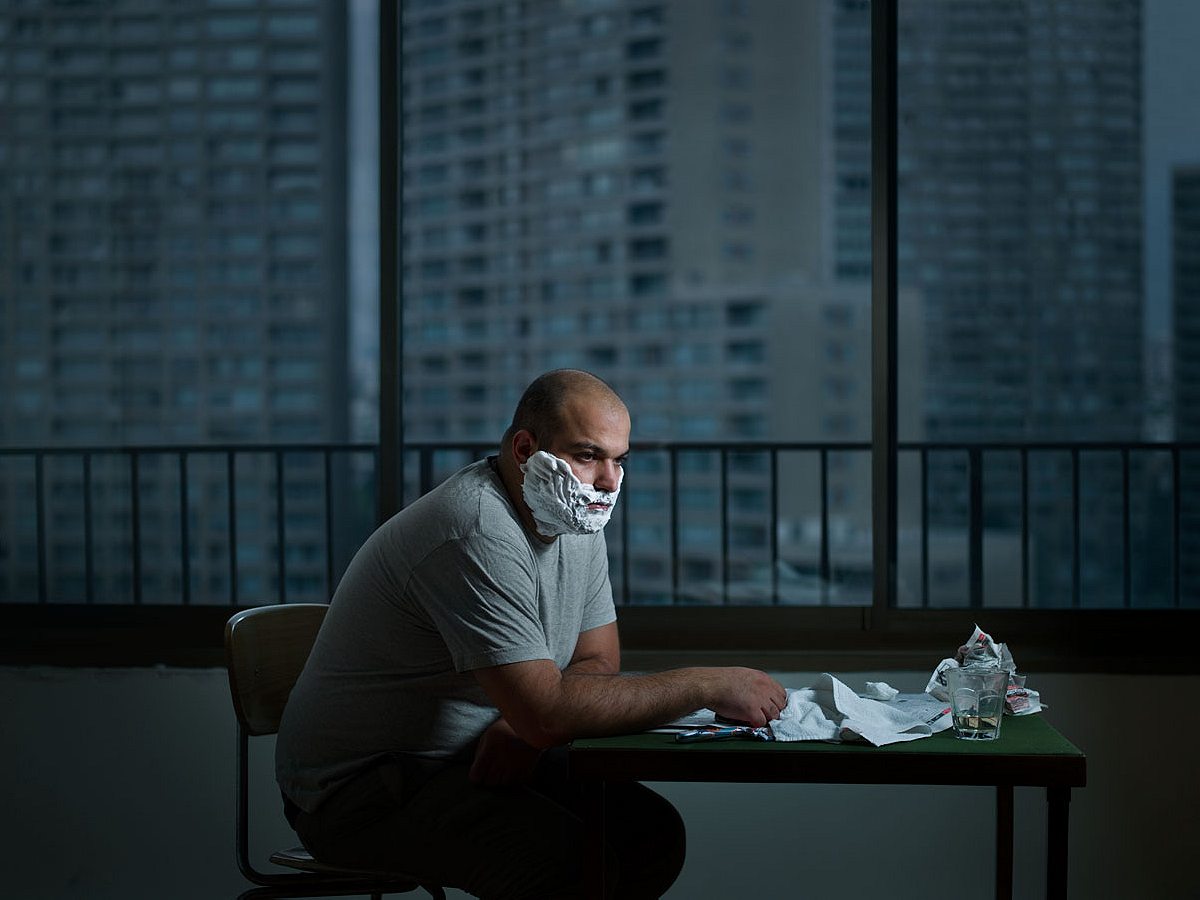

Newsha Tavakolian: LOOK centers on the view from my bedroom window. It symbolizes the feelings of those living in metropolises and in Iran: uncertainty, fear, suspicion, loneliness, and so on.

Instead of making a brochure, I made a two-minute teaser film which I spread through Facebook. In the gallery space there were ten large portraits 110 x 150 cm. At the centre of the gallery stood a 2 x 4 meter installation of the buildings I view from my bedroom—the central idea of the exhibition. From ten windows in the picture, connected by wires, are ten video screens shorting short slow-motion movies of the subjects on the portraits. They’re all neighbors with a connection to the buildings, but not the exact people in the exact apartments.

R&K: LOOK seems to be more art than journalism. Is this a break for you?

NT: In Iran too many people are having trouble on how to label me or my work, but for me it is not really important ‘what’ I am. What really matters to me is telling stories. How I tell them doesn’t really matter (I hope).

R&K: You told Leica’s blog that you were “not allowed to think freely” in the documentary or news realm in Iran.

NT: Naturally in Iran it is more complicated to tell certain stories. Still, if you find the right way of telling them, it is possible. In 2009, following the protests, it became harder to work as a news photographer and I spent six months in my house depressed. After that I started to try new ways—new for me that is—of discussing social issues. Like making installations, photographs and sounds, but still very close to a real (not abstract) subject. I have been doing portraits for a long time, but now I try to connect the portraits so that as a whole they create a story (again in combination with installations, videos and sounds).

R&K: That depression you talk about seems to resonate in LOOK as well.

NT: LOOK is a mix of universal anxieties and a depressed feeling specific to Iran because of the sanctions and mismanagement which are killing the future and opportunity of youth in Iran. It’s not about protests, but about feelings.

R&K: It sort of reminds me of dissident art in Soviet times, fighting a regime with emotions, not politics.

NT: I think that’s a very good comparison. In all atmospheres where the political current is overbearing, others will try to voice their ideas through culture. Personally I don’t like politics, but it is so much a part of our daily lives that I cannot say that it is not political.

R&K: Does this project remind you of your early work with Zan [a groundbreaking women’s newspaper that was banned in 1999], before the student protests in ’99, before the Mousavi protests in 2009?

NT: Zan was famous at a time when the political climate was different in Iran. If there’s any connection between that paper and my work now it is that we are trying to tell stories.

R&K: What did you shoot LOOK with?

NT: A Hasselblad, 50mm. I used a 5D Mark II for the video

R&K: Is Rawiya [a collective of women photographers co-founded by Tavakolian] still together?

NT: Yes Rawiya is still together. After I met Dalia Khamissy and Tamara abdul Hadi in 2008 in Beirut I told them my idea of making a collective, which they thought was a great plan. Three other photographers have joined and we have exhibitions in Great Britain and Sweden in 2013. Also we are involved in giving workshops and so on.

R&K: Are you taking LOOK outside of Iran? What kind of impact do you think it might have?

NT: You probably know what it is like when you write a piece. Maybe you’re worried whether editors and readers will get it. I had that with my exhibition. I was worried whether the audience would understand what I am trying to get across. But during the opening and afterwards the response had been in all honesty overwhelming. There were lots of discussions, in the gallery and online, and in the days after the opening still hundreds of people came to visit. In Iran at least the work covers strong emotions, but also worldwide people feel worried about the future, uncertain and lonely. I certainly hope it will be like my previous “Listen” project, which was shown in LA, Rome, Paris, Dubai and several other places. Still, for me Iran of course matters most.

I am now, however, also planning on doing a similar project in China this year, building further on the idea of uncertainty and metropolises, as I did with LOOK.

R&K: What do you think an American audience would get from LOOK, from seeing the emotional afterlife of their sanctions on Iran?

NT: Naturally the sanctions are hurting people, as they add to their feelings of isolation. But while making this project, sanctions were not the main thing on my mind. LOOK deals with emotions that, in my view, are shared by people all over the world: loneliness, uncertainty, guilt, suspicion and so on. When you also feel isolated, such feelings become even more powerful.