Welcome to Mumbai. Please hit the ground running.

Like an overzealous Alexander heading inevitably toward disaster, Mumbai has expanded its boundaries at breakneck speed in the past two decades (though, thanks to its insane density, its urban footprint remains small compared to similarly populous metropolises). The infrastructure wheezes behind as it tries to keep up.

Thankfully, Mumbai’s famed spirit of ingenuity provides the harried commuter a whole host of small metal compartments to transport her from point A to point B: kaali-peeli (black and yellow) taxis, BEST buses, or 3-wheeler rickshaws, which weave ingeniously through suburban traffic (they’re not welcome in South Mumbai) thanks to their ergonomic design and fearless spirit. But the fastest—and, naturally, most congested—form of transit is the local train system.

Conceived initially by the marauding British, the Mumbai train system has 3 lines running through the heart, soul, and underbelly of India’s greatest city. Today, the Mumbai railways ferry an unbelievable 7.5 million people each day, from the northernmost exurbs, down through the gauntlet of the inner suburbs, and all the way to its pincer-shaped historic tip. Imagine watching the entire population of Denmark, and then some, rush across the country each day to get a sense of those numbers.

Navigating the Trains

The Mumbai Suburban Railway is divided into three lines: Central, Western, and Harbour.

The Central Line

This line consists of 3 major corridors, which branch out as they move into the city’s suburban satellite towns. The line starts from the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (CST), one of the city’s most recognizable landmarks, and a heartening reminder for Mumbai’s nouveau riche that even the most extravagantly overzealous decorating job can age into something beautiful with the right amount of wear and tear. (We’re looking at you, Antilla.)

The Western Line

Runs parallel to the Arabian Sea, starting at Churchgate station. Passing through most of the city’s tonier neighborhoods, the Western Line might be considered the most ‘upmarket’ of the three lines. The trains are from this millennium, and the crowd is…well, of more or less the same in density, but with a few extra rupees per pocket.

The Harbour Line

Runs from CST to Andheri and Panvel. Do not expect to exit the train onto a coastal dreamscape. You’d have to navigate a post-industrial wasteland and some of the most criminally wasted land (held in trust by the Mumbai Port Trust) to get anywhere near the water.

The Metro

In an effort to acknowledge that Mumbai’s “suburbs”—each a sea of identical concrete towers denser than the densest city center in the US or Europe—are growing faster than its traditional population centers, the city’s Municipal Corporation, the BMC, decided to build semi-connected Metro lines running east to west across the city’s broad mid-section. For most, the BMC’s aggressive Metro expansion mostly registers as yet another addition to the city’s perennial traffic woes. The new lines being built, however, promise to connect greater parts of the city, from the historic South to the metastasizing North, even connecting to some of the city’s oft-neglected central districts. 2019 is the promised deadline, but even Nostradamus wouldn’t venture a guess on the actual completion date for a Mumbai infrastructure project.

A Station Guide

Let’s begin with the three cardinal points for most visitors to city, namely Churchgate, CST, and Dadar. Think of these stations as your polestars.

Churchgate Station, the southern terminus of the Western Line, is the daily pit-stop for much of Mumbai’s briefcase-toting workforce. It’s also the station visitors most often use to access the city’s historic southern tip. Marine Drive, the seaside promenade immortalized (over and over again) in Bollywood love songs, and home to the second-largest assemblage of Art Deco buildings outside Miami, is just a few steps away. Necking teenagers, portly joggers, and vendors selling steaming chai, balloons, and savory snacks, make perfect accompaniments to gorgeous, hazy sunsets.

Colaba Causeway, lined with stalls and shops, and the main thoroughfare through the neighborhood where most visitors end up staying, is a five-minute cab away. The Taj Palace Hotel and the Gateway of India, the latter an elaborate arch built to welcome King George V and Queen Mary in 1911, and the departure point for the last English soldier to leave 36 years later, are the area’s two most recognizable landmarks. Weather permitting, the walk from Churchgate to Colaba is among the most enchanting the city has to offer. Leaving the station (there are several exits, but don’t worry, they all lead to more or less the same place), head east toward Flora Fountain or south past Eros Cinema and along the Oval Maidan, lined by leaning palms, the Victorian Gothic turrets of the High Court, and the whimsical Rajabai Clocktower, built by the founder of the Bombay Stock Exchange who provided funds for its construction on the express condition that it be named after his dear old mum. The Oval is generally swarming with amateur cricketers who monopolize one of the rare open green spaces in the city.

Right outside Churchgate, the first restaurant you’ll see is a Burger King. Nod respectfully to capitalist monopolization – an unfortunate consequence of a globalized 20th-century India—then walk swiftly past it to the main road. Right around the corner you’ll find Stadium Restaurant, a classic example of the city’s disappearing Irani Cafés, the first democratic dining institutions in the city, founded by Persian immigrants around the turn of the 20th century. The mutton kheema and egg akuri are both musts. If you fancy a croissant on a budget, then the iconic Gaylord bakery is a great place to pick up a snack. Alternatively, for a smorgasbord of street food, the famous Khau Gully next to Azad Maidan is a short walk away. The name translates to Food Alley and it lives up to it: dosa, vada pav, chaat, pav bhaji, Bombay toast, dabeli—you name it, it’s there. Rely on your senses (and the crowds) to pick the right stall.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST)

CST is the headquarters for the Central and Harbour Line, a UNESCO World Heritage site, and Churchgate’s counterpart for South Bombay’s eastern neighborhoods (most of the sites mentioned above are pretty easily accessible from here, too). Once called Victoria Terminus, it is now referred to as CST in maps, guides, rail platforms, and news articles. For all practical purposes, though, it’s still known in the popular imagination as Victoria Terminus, or VT for short.

Built in 1888, it is arguably the finest example of Victorian Gothic Revival architecture in the city, flamboyantly jazzed up with decorative elements drawn liberally (and perhaps a bit haphazardly) from around the subcontinent. European gargoyles pose alongside carved stone screens in the shapes of peacocks and portrait roundels of the influential gentlemen of a bygone era. If the structure intrigues you, there’s a Heritage museum located within the premises, in the right wing. Like many government officers, it only serves the public on weekdays for a brief and unpredictable window of time.

From CST, walk down beautiful DN Road toward Flora Fountain, making sure to stop at the government handcraft emporium, Khadi Bhawan, for beautiful handloom textiles by the yard and a master class in indifferent service. Wayword & Wise is a lovely boutique bookshop on your way to Ballard Estate, an odd bit of Banyan-bound British urbanism in the tropical heat, and home to the famed Britannia & Co. Restaurant, where you will almost certainly stop for a plate of Berry Pulav. Off DN Road, and before reaching Flora Fountain, you might stop at Taste of Kerala (or its equally accomplished neighbor, Deluxe) for a delicious vegetarian thali from the southern state of Kerala, accompanied by fish or mutton fry (don’t forget to order flaky rounds of Malabar paratha to mop up the gravies).

If you’re in the mood to shop, head north, past the headquarters for the Times of India (the world’s most widely read English-language publication) and the JJ School for Architecture to Crawford Market, where hucksters will try to foist cut-rate spices on you (check out the reliefs over the doorways, carved by Rudyard Kipling’s father). Past Crawford Market is the beginning of what, in the colonial period, was known as the Native Town. It starts with Mangaldas Market, an immense covered fabric market in the shadow of the extravagantly ornamented Jamma Masjid, and your gateway to a dense tangle of bazaars for everything from costume jewelry to antiques. Stop at Badshah restaurant to treat yourself to a local milk-based concoction called Falooda, which means a medley.

Dadar Station

Dadar is, for many, the most central place in town; all roads and train lines (except the Harbour) seem to lead here. If you find yourself in the unenviable position of having to switch rail lines (hint: avoid this at all costs), Dadar is likely where you’ll be doing it. During rush hours—which, at Dadar, is pretty much always—expect screaming hordes of travelers both alighting and boarding trains in continuous synchronicity.

If you stop at Dadar, exit the station to the west and descend the rickety stairs into the Dadar flower market. Best experienced early in the morning, it’s an entire stretch of floral negotiations, as sellers, who travel here from across the sprawling state of Maharashtra (home to more people than Mexico), hawk brimming baskets of jasmine, rose, and marigold to smaller vendors and individual buyers alike. Never has chaos smelled sweeter.

Dominated by the local Marathi-speaking community, Dadar is also an excellent place to sample specialties from the surrounding state. Try Aaswad for simple and traditional Maharashtrian food. Our picks would be the Misal Pav and Sabudana Vada. Sindhudurg is another local Maharashtrian pick, that offers affordable seafood dishes from the Konkan Coast, which runs south from Mumbai through Goa.

Other Important Stations

Western Line

Grant Road: This is one of the older stations on the Western line. Right outside the East exit, you’ll run into Merwan and Co. It’s another quaint Irani café, that hasn’t changed a bit in its century-long existence. The menu is so stark that the waiters will list the available items impatiently on their fingers. Every few years they threaten to shut down, inevitably attracting a half dozen newspaper elegies and days of long lines that, by a happy coincidence, keeps them going just a little while longer. Get down on the west side of the station and you’ll walk directly into the Grant Road Bhaji Galli, one of the city’s most interesting produce markets.

Bandra: Bandra station is notable for its elegant stone façade, straight out of the English countryside, and for being the first “suburban” station. I’s arguably the city’s the hippest neighborhood. Come for a wander in what remain of the old fishing villages (ask for Ranwar, Chimbai, Pali, and Chuim), for a sunset stroll down the Bandra Bandstand promenade, and for a glimpse of where Bombay’s bright young things spend their evenings.

Andheri: Andheri, populated by young professionals and film people, a land of identikit apartment blocks and malls and second branches of all the fancy-ish places that open first in Bandra or Colaba. Though Harbour and Central Line trains run intermittently from Platforms six and seven, this is principally a Western Line station. With the dense, mad rush that plagues it at all hours of the day, the station in Andheri—which some aptly translate as The Dark Place—might well be called Anarchy Station. Merwan’s bakery—unrelated to the Irani Café at Grant Road—is a delicious pit stop if you find yourself on the West side. If you find yourself on the East, cross over quickly to the West before the pandemonium consumes you.

Borivali: This suburban station is also the best access point to Mumbai’s largest/only green patch: the 64 sq. mi. swath of jungle that is the Sanjay Gandhi National Park, famously home to the world’s only urban leopard population. Thanks to the city’s unchecked urbanization, they occasionally stray into what is now human habitat for prey. For casual visitors, leopards don’t pose much of a problem. Come for a break from the relentless urban landscape. Tours along the park’s nature trails are available at the entrance.

Central/Harbour Line

Sandhurst Road: This station is your gateway to Chor Bazaar—literally the “Thieves Market”—which gained a reputation 150 years ago for brokering stolen and smuggled goods. Today it’s one of the largest flea markets in the country, where, with a bit of luck and expert haggling, you can score some antiques at a steal (pardon the pun). Don’t let the name scare you, it’s quite safe. The most likely daylight robbery will come in the form of inflated prices. If you’re not in the market for antiques, the surrounding area is the best place in town to sample specialties like kebabs and Bohra-style khichdi from the city’s large Muslim population.

Byculla: One of the oldest stations in the city, Byculla was once another hub for textile mills, as well as an access point to what was, for the first half of the century, a relatively upmarket residential district. Adjacent to what was once the city’s wholesale produce market, Bycull Station is an easy walk one form two important landmarks, the Byculla Zoo (officially named Jijamata Udyaan) and the Bhau Daji Lad Museum. Give the zoo a skip—conditions are more likely to spark concern for the animals than curiosity—and head straight to the Bhau Daji Lad Museum. Built as the Victoria and Albert in 1857, it’s one of Mumbai’s finest examples of restoration, a Renaissance Revival bauble in seafoam green.

Useful Survival Tips for Your Journey

Do not mix

Compartments on the Mumbai local trains are divided between ‘Ladies’ and ‘General,’ with the ladies carriage helpfully marked with a drawing of a modestly veiled lady and, less helpfully (but more mysteriously) with green stripes. The ladies coach is usually less crowded than general and far less likely to transport oglers. While boarding, keep an eye out for coaches reserved for the old and infirm, marked with a crab (like the zodiac symbol: cancer).

Class Wars: Attack of the Crowds

By coughing up a little more money for First Class (Rs. 90 between Churchate to Andheri vs Rs. 10 by Second Class), you’ll still get a crowded compartment but with seats that have a bit of cushioning, which, on a hot day (i.e. virtually any day) is actually less comfortable than the hard plastic seats in the plebe cars. Fortunately, your chances of experiencing these seats are slim, unless you’re travelling at uncommon hours. The primary benefit to riding in First skipping the line at the ticket counters. You’ll buy your ticket at the same window as everyone else but can cut around to the left of the line and approach the window directly. It’s worth the extra few rupees.

Open access

To avoid lines entirely, you can also try your luck riding ticketless. The local trains have no turnstiles, no place to swipe, no slick electronic screens to tap. Platforms are open; the trains don’t even have closed doors. Be forewarned: you might encounter a disgruntled railway employee checking de-boarding passengers for tickets who will fine you something like 500 rupees if you can’t present a ticket from that day. These employees are experts at reading guilty body language, particularly from obvious firangs (or foreigners). We can’t endorse this behavior in any official way, but if you’re fond of low-stakes gambling, this might be the game for you.

Can’t keep us apart

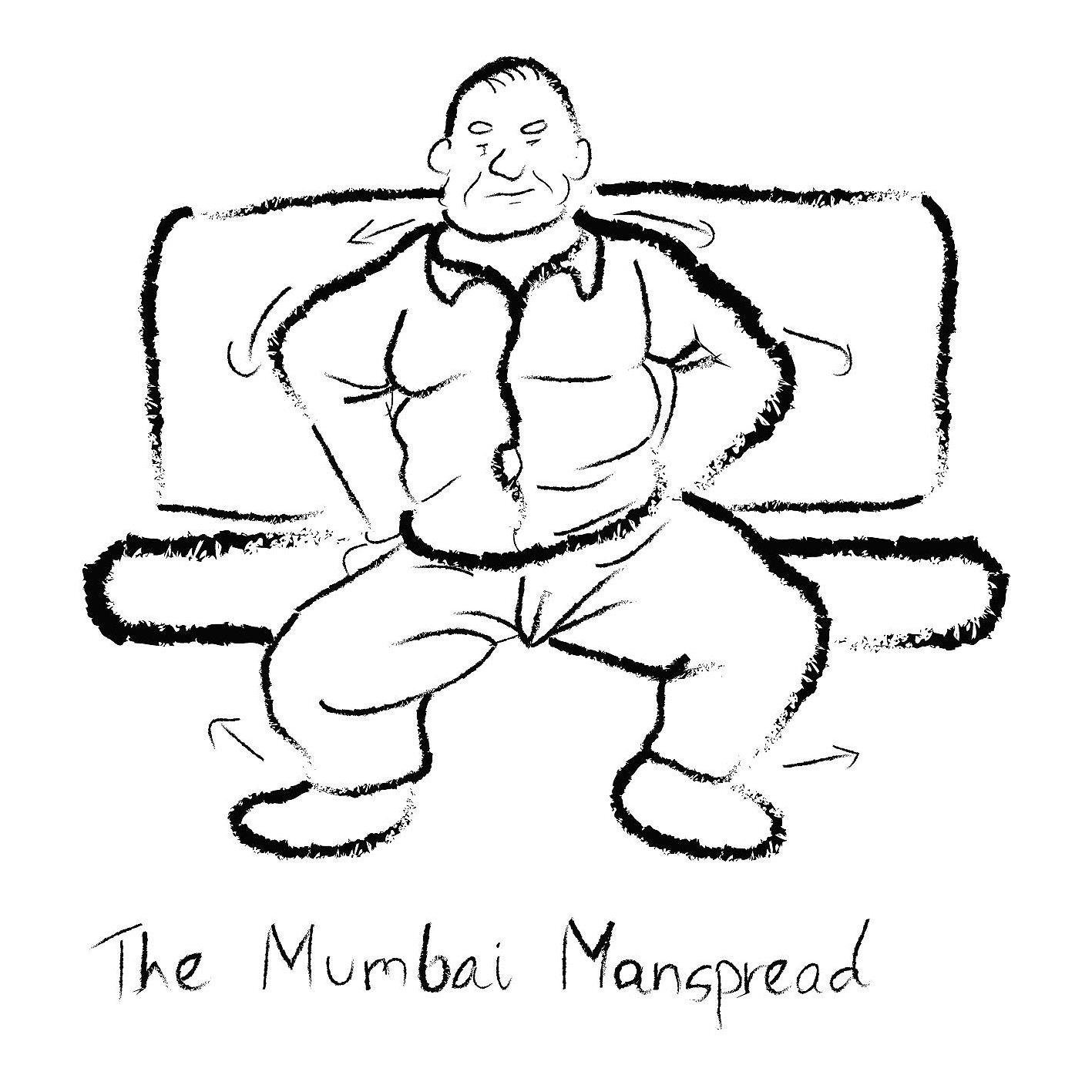

Manspreading is not considered rude but an essential technique for claiming one’s tiny patch of space, the same way that wild animals puff up their chests for intimidation and dominance. Extra points for shoulder extension.

Adjust your expectations

In the Second Class compartment, you must also be prepared for the converse of manspreading. A fourth individual joining you on a 3-person seat—a sliver of space known as “the fourth seat”—is par for the course. The fourth individual must be content with half a butt-cheek of seating, but, in a city as starved for space as Mumbai, that’s worth its weight in gold.

Girl on girl, guy on guy action only

Touching between sexes is a strict no-no. Touching/schmoozing/smothering between the same sex is both normal and excessive.

Google Chaps

f you’re lost, ask around. Mumbaikars (as folks who live here are known nowadays) are an extremely helpful lot when it comes to directions and advice.

The fast and the spurious

Like the express and local lines in New York, Mumbai trains run on the more bluntly named Fast and Slow tracks, marked on the electronic indicators that hang over the platforms, as either F or S. Fast trains, as the name suggests, are intended to get you where you’re going faster by skipping some of the smaller stations along the way. Given the city’s obsession with (and ironic ineptitude at) saving time, it’s no surprise that the Fast trains at peak hours make the slow trains look like the Paris Metro on a Sunday. Opting for the Fast train at times like these is a game of Russian Roulette, with the bullet being the pleasant outcome. Otherwise they can be a genuinely efficient way to get where you’re going.

All indications point to confusion

Alan Turing would have had a tough time decrypting the Mumbai train indicators at first glance. So here’s a quick rundown on the elements you would find, on a working electronic indicator. There’s the final station destination, in abbreviated form, such as C for Churchgate, or V for Virar. Then comes the current time. We’ve already covered the F or S for Fast and Slow. And last, on the extreme right, are the estimated minutes to arrival on the platform. The largest indicators show all this, and also the stations it will stop at (if it’s a Slow), or not stop at (if it’s a Fast).

Leap before you look

If it’s the last stop on your route, then patiently wait for the train to completely halt and fill up with eager passengers before alighting. If you’re getting down en route, particularly at a busy station, you may run into a counter force that won’t patiently await your exit. Be patient in such cases, and allow the crazies to board first. Generally speaking, it’s wise to keep an eye on where you are and only move toward the ‘doors’ immediately before your station, lest you get carried unwillingly off the train. You’re likely to see that locals get down—or jump on—long before the train comes to a halt. Don’t. These stunts are best performed by professionals.

Hang out, inside

The open-air design of the trains (i.e. their lack of doors), combined with sweltering heat and suffocating crowds, might make the preferred position of some passengers—leaning out on the footboard into the oncoming rush of fresh-ish air—seem tempting. Resist the urge. Plenty of people die on Mumbai locals every year and this is one of the key contributors to those awful numbers.

The silver lining on the metallic compartments

Train travel in Mumbai can be harsh, but it also captures one of the defining traits of this immense city and its citizens: the ability to adjust. It’s the seemingly impossible accommodation of another body on a crowded footboard, the young lady who offers her seat to the elderly one (the equivalent of surrendering hard-won treasure), or the uncomplaining man who has a stranger’s bone-tired head resting on his shoulder. Ride enough and you’ll begin to notice a special kind of camaraderie here, born not despite the hardships, but because of them, which, really, is Mumbai in a nutshell. In the end, we’re all headed to the same destination.