Photographer Simone Sapienza speaks to R&K about how his series, “Charlie Surfs on Lotus Flowers,” finds new ways to depict modern Vietnam.

Over 40 years after the U.S. withdrew its troops, Vietnam, a one-party socialist republic that started making free-market reforms in the 1980s, is often described as one of the world’s fastest-growing economies. As generations have come of age far removed from the country’s post-war poverty, it has developed a booming middle class, and Vietnamese citizens have overwhelmingly favorable views on the U.S.—and on the free-market economy.

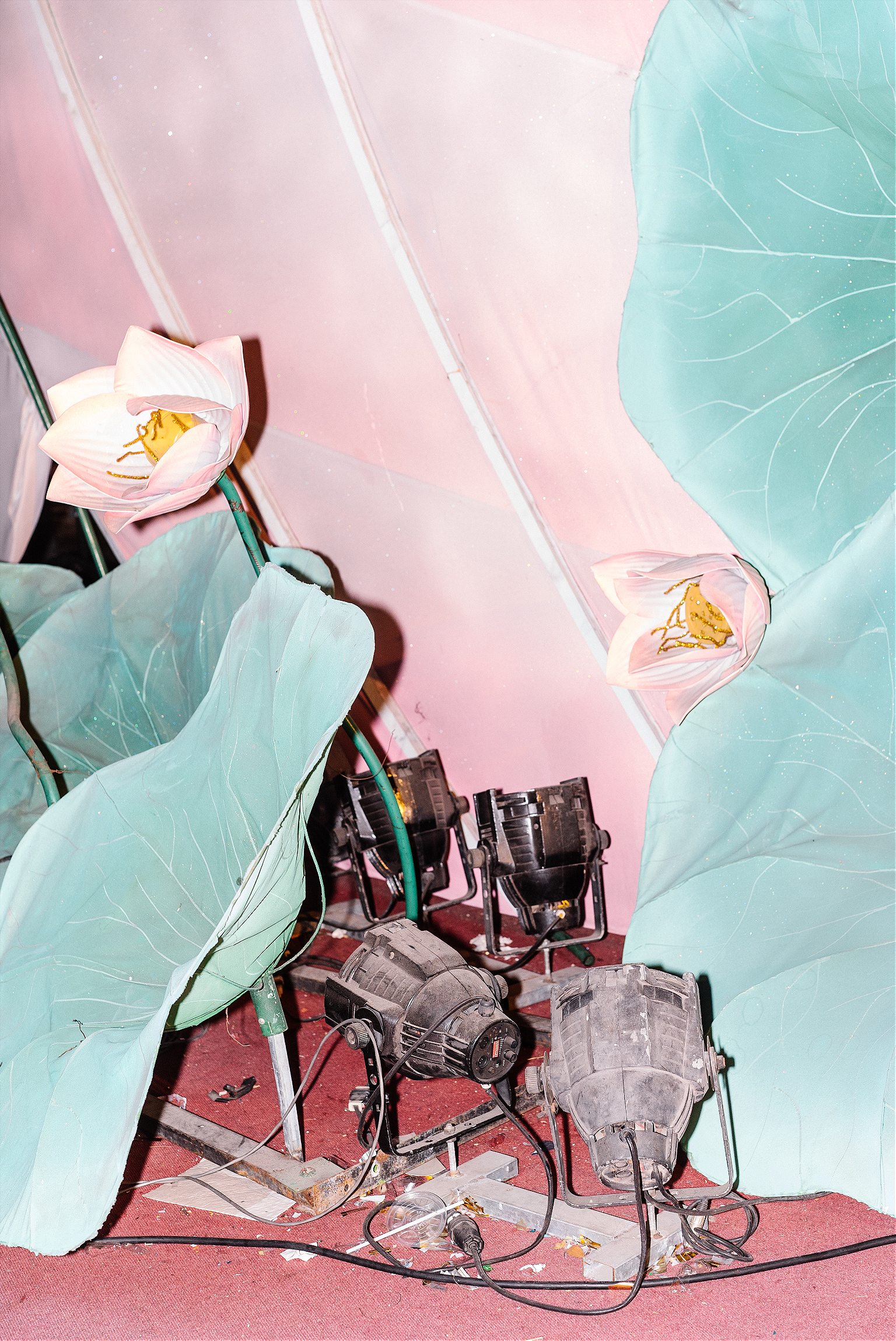

During his travels in Vietnam, Italian photographer Simone Sapienza became fascinated by the way Vietnamese society is embracing Western culture and ideals, while at the same time Vietnam’s Communist Party tightens its grip on the state, the media, and speech. He explores this contradiction at the heart of post-war Vietnam in his series, “Charlie Surfs on Lotus Flowers,” recently published as a photobook by AKINA. Sapienza departs from traditional documentary photography by depicting modern Vietnamese culture through metaphors, such as the national flower, the lotus, and red backdrops. He also references archival images to create a visual connection between the country’s past and present—illustrating the tension between the freedoms that economic momentum has brought its citizens and the government’s enduring control.

Roads & Kingdoms’ Emily Marinoff talked to Sapienza about how he developed the project, finding new ways to tell stories about Vietnam, and why he chose not to use captions.

Emily Marinoff: How did the idea for this project start?

Simone Sapienza: This began as a graduation project from my university. I was studying documentary photography at the University of South Wales in Newport. I was really interested in war photography, specifically the Vietnam War, because I didn’t learn about it at all in my studies when I was younger in Italy. My only knowledge of Vietnam came from Hollywood movies about the war and National Geographic-style travel pictures. I started to research Vietnam and learned a lot about the economics of the country, which made me realize that the new Vietnam does not resemble the communist country it’s supposed to be.

Marinoff: What does the title “Charlie Surfs on Lotus Flowers” mean?

Sapienza: Charlie was the American nickname for the North Vietnamese army, the Viet Congs. In the film Apocalypse Now there is a famous scene where a lieutenant says to the American soldiers ,“Charlie don’t surf.” Surfing in the South China Sea was the one of the main hobbies of the American soldiers, so in the movie that phrase implies that leisure activities only apply to Western people. Somehow this has changed. Now, the Vietnamese are looking more and more to the Western countries after being freed of them. The lotus flower is a symbolic flower for the Vietnamese. To me, it’s a metaphor for Vietnamese citizens creating a new future after occupation by the French and then the Americans.

Marinoff: Why did you decide to present your ideas about the current society and economy of Vietnam in metaphors rather than through pure documentary journalism?

Sapienza: I traveled four times to Vietnam in three years, because it takes some time for me to understand a new country. At the beginning I was looking more at action that could describe the main topics I was thinking of, but I got sick of this approach. Trip after trip, I looked at more archival photos of the Vietnam War and only after deep research did my more abstract ideas come about. Famous archival pictures inspired me to make new ones. I wanted my pictures to seem like a consequence of past events, which gave me an excuse to me to go out on the streets of Ho Chi Minh City and find references to old images. It was a nice balance between the subject and my personal approach.

I decided to not use captions to leave people free to interpret the pictures for themselves. It’s more difficult, but it forces everyone to really think about the project, which is more inspiring for me as well from the other side.

Marinoff: Can you give me an example of one of your photos that is directly inspired by images you found in your research?

Sapienza: There’s a picture with a tourist bus going through a gate. That was the same gate through which the Viet Congs entered the Independence Palace on the day of the fall of Saigon, and there is a famous picture of it. I also drew from photos of the Viet Congs living the inside the Cu Chi Tunnels. In my pictures you can see a tourist guide in the tunnel wearing the same uniform of the Viet Congs. He’s putting on a show and guiding a tour group inside the tunnel.

Marinoff: Were some of your pictures staged to mirror the archival photos?

Sapienza: Some of them were posed, but none were staged. There are some pictures referring to the concept of a stage, though. I put up a studio on the sidewalk in the financial district of Ho Chi Minh city, formerly Saigon. I just put this red background on the sidewalk and set up lights and then people just passed by. A few of them posed but most were really just passing by. They didn’t even know what was going on.

Marinoff: You’ve also mentioned that you wanted your photography of Vietnam to depart from picturesque travel photography. Can you talk more about that?

Sapienza: Instead of going into Vietnam and photographing the landscape I wanted to find something more fascinating and specific to the Vietnamese population. I was looking for something that is not your classic postcard, but tells a specific story that still depicts the daily life of Vietnamese culture.

Marinoff: What has the reception to this project been like?

Sapienza: We published some photos in a Vietnamese magazine and there was one photo they didn’t want to include, to avoid problems with the government. It was the photo of an officer during the anniversary of the birth of the Vietnamese Communist Party, and he looks kind of funny because he has one eye closed. The magazine didn’t want to publish it because they were scared that it commented too directly on the government. That’s the only photo they didn’t want me to publish, but that’s when I really felt the control the party has.

It’s always challenging when you create work on a country or culture that is not your own. There were some public exhibitions of my work in Vietnam, India, and China and it was interesting for me, because it let me create a relationship with the local people.

Marinoff: Did this project make you think a lot about the responsibility of documenting a culture that is not your own?

Sapienza: I realized that everyone is always going to have a different point of view. If I take pictures in my home country it would be different from pictures that a foreigner takes in Italy. It’s always subjective and I don’t think any person’s perspective is more true, just different, whether you’re a doing documentary photography or a personal project.

This conversation has been condensed and edited.