A photographer speaks to R&K about the issue of identity among the Madhesis, Nepal’s marginalized community that has had to continually fight for equal rights and representation as the rest of the country.

When Nepal was on the verge of adopting a new constitution three years ago, it was a historic moment—one that followed decades of unrest in the country, including a bloody civil war that saw thousands of people killed.

But the constitution wasn’t welcomed with equal enthusiasm by all Nepalis. Many members of the country’s traditionally marginalized groups argued that the constitution was too rushed, and was being implemented without addressing their demands for equal representation and rights. One of those groups were the Madhesi people, who live in the country’s Southern plains, alongside the Indian border.

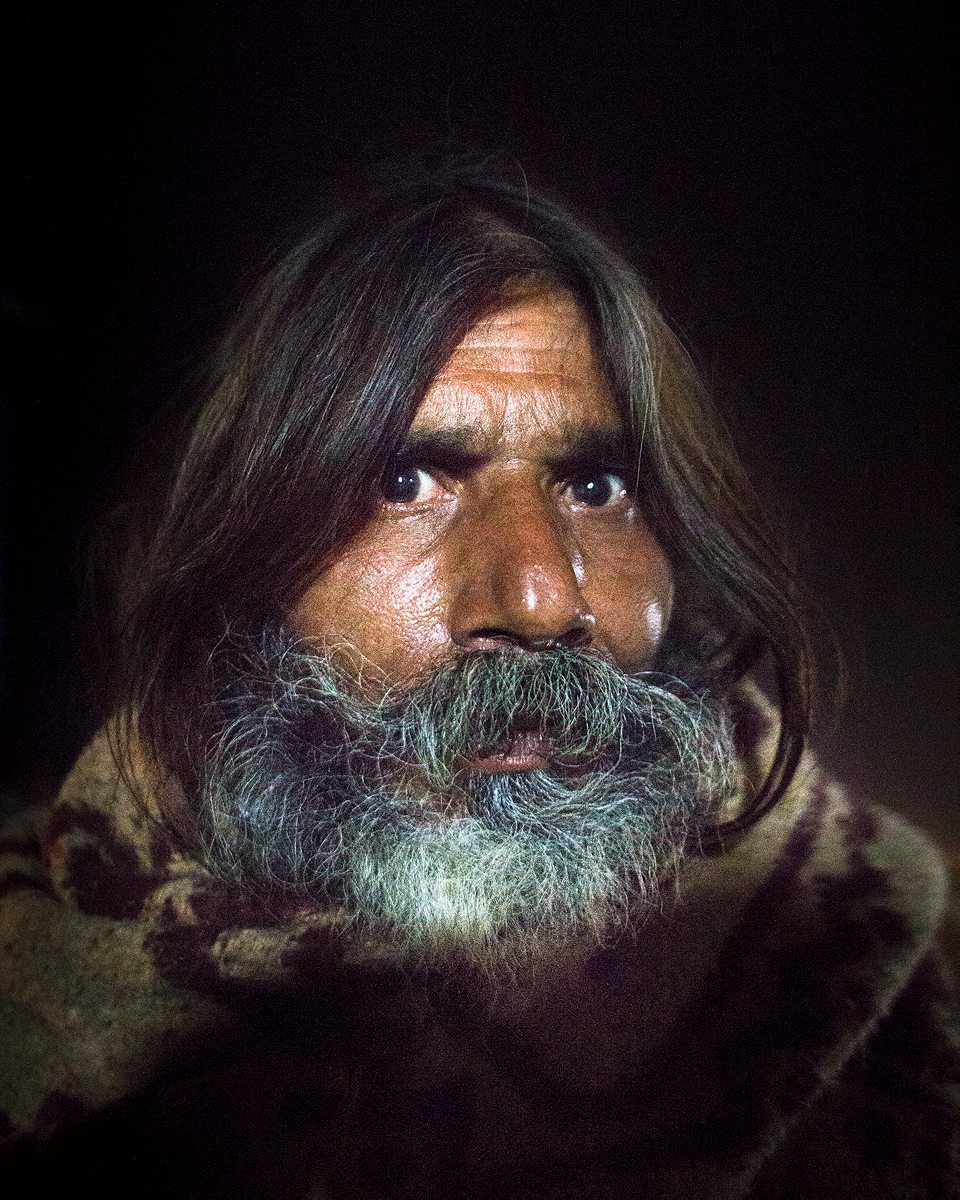

Earlier this summer, Nepali photographer Sagar Chhetri was one of the eight photographers who received the Magnum Foundation Fund grant. Chhetri, who approaches his subjects from a unique—and rather abstract—viewpoint, received the grant for his project Eclipse, which highlights the issue of identity among Nepal’s Madhesis.

R&K Photo Editor Cengiz Yar spoke to Chhetri about his project, and why the issue of Madhesis continues to remain a contentious topic in his country.

Roads & Kingdoms: Can you help us understand the tensions between the people who live in the south with the rest of the country?

Sagar Chhetri: Nepal has around 125 ethnic groups and more than 123 different languages. It has rich diversity, but the country is also divided culturally. Over the years, Nepal has been governed by an upper-class group of castes—the Brahmins and the Chhetris—who mainly come from the hilly areas of Nepal. There’s an ethnic group that comes from the Madhesh, the flat lowlands of Nepal, along the border with India. These people, known as the Madhesis, have historically been sidelined by the establishment, and as a result, they feel disregarded and detached. They don’t feel well-represented in the organization of this country.

R&K: Why don’t the Madhesis feel represented?

SC: People in the Madhesh say most Nepalis in the capital, Kathmandu, think they are of Indian origin, and therefore, hold a sense of prejudice. Their culture and language are close to those of people across the border in India, so they are often dismissed as Indians, and have their national identity questioned. The Madhesis are the indigenous group of Nepal and have been living on this land for centuries. They are every bit Nepali as those living in the hills or elsewhere. This question of identity and the plight of being historically sidelined has left the Madhesis, again and again, heartbroken.

R&K: What sparked your interest in this tension?

SC: The ambiguity and ambivalence that exists around the identity of the people of the Madhesh. As I was born and raised there, despite being a non-Madhesi, this region is close to my heart. My interest is to understand the identity struggles of my Madhesi peers. I wanted to look into how this border region has been a salient incubator of political grievance and is home to one of my generation’s biggest fight for identity.

When the second Madhesh uprising was unfolding in protest of the new constitution, the streets in several cities of Terai, along the Nepal-India border were packed with demonstrators, and the protest was getting more violent each day. While many parts of Nepal welcomed its new constitution, a major group of indigenous Nepalis was calling it a Black Day, pointing to some provisions that left the concerns and demands of the marginalized groups largely unaddressed.

The protests were mostly centered around the city of Birgunj, where protestors had shut down a bridge that spans the Sirsiya River between India and Nepal which also happens to be the economic lifeline of the country. The protests went on for five months, and the blockade at the border was a huge blow to the country that was barely recovering from the devastating earthquake earlier that year.

R&K: What did you focus on initially?

SC: I was photographing the clashes between the police and the Madhesi protesters for a few days in the beginning, but the images I was capturing were just so monotonous and didn’t carry any depth of the real story. So I quit photographing the protesters, police, and the clashes. I shifted my attention from the streets to the villages around the city. I went around and started interviewing people about Madhesh and what it feels like to be a Madhesi. Do they really feel that the protest is a worthwhile action, or do they oppose the protests? That’s how this project began, by trying to explore the idea of ambiguity and ambivalence among the Madhesi people about their own identity.

R&K: What role does the border play in the situation?

SC: Nepal and India share an open border. It does not have a wall or a fence. It doesn’t even have many clear markings. You can freely enter India, and the Indian people can freely enter Nepal without being stopped.

The Nepali people who live in the border area have a strong relationship with the people across the border. People often have relatives in India because it is common to get married with a family across the border. The role of the border here is also to cut a community, culture, lifestyle into two different national territories, hence leaving a room for a huge debate and identity politics.

Related Reads

R&K: Is this denying and suppression of rights increasing resentment among the Madhesi people?

SC: There are some actions of radicalism coming into play. Many of the Madhesi youth are starting to think that their own country does not care about them. They feel that the establishment denies their Madhesi heritage. They are beginning to be more skeptical regarding their future as an equal citizen; that makes them afraid, angry, and anguished.

R&K: What’s it been like since the protests?

SC: There aren’t many protests happening in the streets these days, compared to the situation back in 2015. But the story of how the Madhesi are being treated is the same.

R&K: Are the Madhesis expressing their identity struggle with you directly?

SC: Yes. Once I was conducting an interview with a young Madhesi man on the very bridge where the blockade happened in 2015. “Why don’t the Madhesis separate themselves from Nepal?” he told me. They were so angry that they want their own state. They don’t want to be part of a country that neglects them. A friend that I got to know, in Birgunj, told me, “When we go to Raxaul (India), we are identified as Nepali and when we go past Simara (further up into Nepali territory) we are called Bihari (people of Bihar, India). We must belong to a country. Who are we? We are seeking our identity.”

R&K: Have you had any interactions while working that really stood out to you?

SC: An interaction that stood out to me happened one night when I was photographing in the streets around villages. In the evening news, there was a report that one of the senior political leaders was injured in a protest. That news created more tension, and a group of Madhesi protesters started to become violent. They went around the streets trying to ask people to shut down their shops. They lit up torches and started burning tires on the streets, chanting slogans.

At the same time in the city hall, a few hundred meters away, there was a freestyle hip-hop dance competition with a lot of teenagers. They were just dancing. So, at the same time in the same city, there was a place where young people were dancing inside and outside in the streets, there was this heated protest going on. Tires were burning, people were shouting at each other and trying to start a strike. It was very bizarre and very interesting to me.

R&K: How do they view the rest of Nepal, specifically Kathmandu?

SC: When I was working on this project, I felt this strong sense of nationalism among the Madhesi people. They were fighting against the government, staging a blockade, being accused of treason, but in reality, they have this very strong connection to their country. That was so vivid in many things they said to me.

They view this country as their own, so they want to fight for it right now. They don’t want to be left powerless among the powerful. Now they want change.

When the demarcation of the country’s provinces was announced out in 2015, State Two, where many Madhesi people live, got the smallest piece of land, and they were not happy. The allocation of resources was less in this new state which again left the Madhesis to feel the same historic repression of the state.

R&K: What do people need to understand about the Madhesis and their situation?

SC: Politically, I would expect the establishment to listen to their voices and address their demands. They belong to this country and they deserve every single right that this country offers to its citizens.

People need to understand that the Madhesis are Nepalis.

R&K: How is life different between the areas where the Madhesi people live and the rest of Nepal?

SC: Nepal is a developing country and it relies heavily on remittances. Basically, a major chunk of the population is working abroad in Gulf countries, and others, who come from the cities, live and work in Europe, the United States, among other western countries. In the hilly parts of the country, people rely on agriculture.

The Madhesis’ lives don’t differ much from people in other cities in Nepal. They are also heavily reliant on agriculture and remittance. The problem right now is the feeling, again, that they are not well represented in the public service areas, in security agencies, especially in the army and the police.

Daily life is more or less the same. They do business, they do farming, they do agriculture, they are involved in foreign jobs, and they work as laborers.

R&K: You said young men in these areas are becoming radicalized or disillusioned with the government. Would you say this is indicative of young men anywhere in a disenfranchised position or is it different?

SC: This was a question that I also asked a political figure when I was working on this story. He said, and I think I agree with him, that when such movements happen there is always a force of young people who have been major, major contributors to such movements.

The same thing is happening within the Madhesi movement. These young people who are guided by the political leaders, so they are expressing their anguish on the streets.

R&K: How do you see your project evolving over the next few years?

SC: When I started I just wanted to know what was going on there because I didn’t trust the news that was published in most mainstream publications. I thought that because I was a photographer, I should go and find out for myself.

But when I went around and spent more time, I started to find there were so many layers to the issue. The interviews I have been doing are very powerful. And my photographs are a bit different than other images published in local newspapers. I want to focus more on identity now. Maybe the project may become a book, but it might take surely some time to shape the project.