After 30 years of service in Sudan, often defying her superiors’ orders, a remarkable Indian nun is forced to ask herself whether she’s made any difference at all.

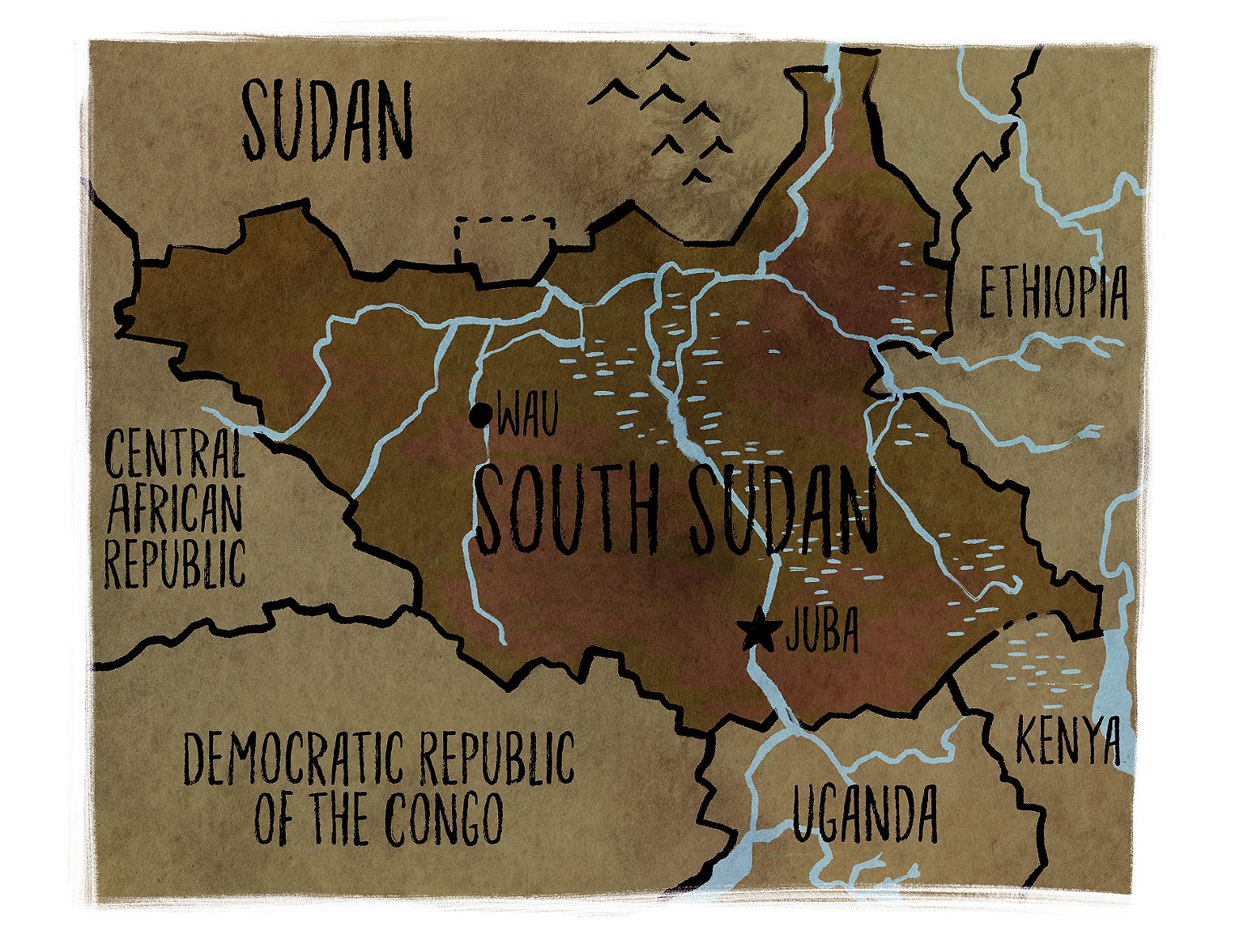

Ground Zero in the City of Wau

Sister Gracy sits on the edge of her seat as she guides her Landcruiser through the back roads of Wau, South Sudan. She knows every dusty path by heart. At five feet tall, she barely clears the steering wheel. She smiles as she peers over the dash, keeps a rosary hanging from the rearview, and has a habit of grinding the gears when she’s distracted, as she is now. The 60-year-old nun has one hand on the wheel while the other points out the demolished huts that pass by, burned down and bombed out. Furniture, grain sacks, family photos, remnants of looting litter the roads. We keep an eye out for military patrols, chop-top camouflage pickups mounted with machine guns.

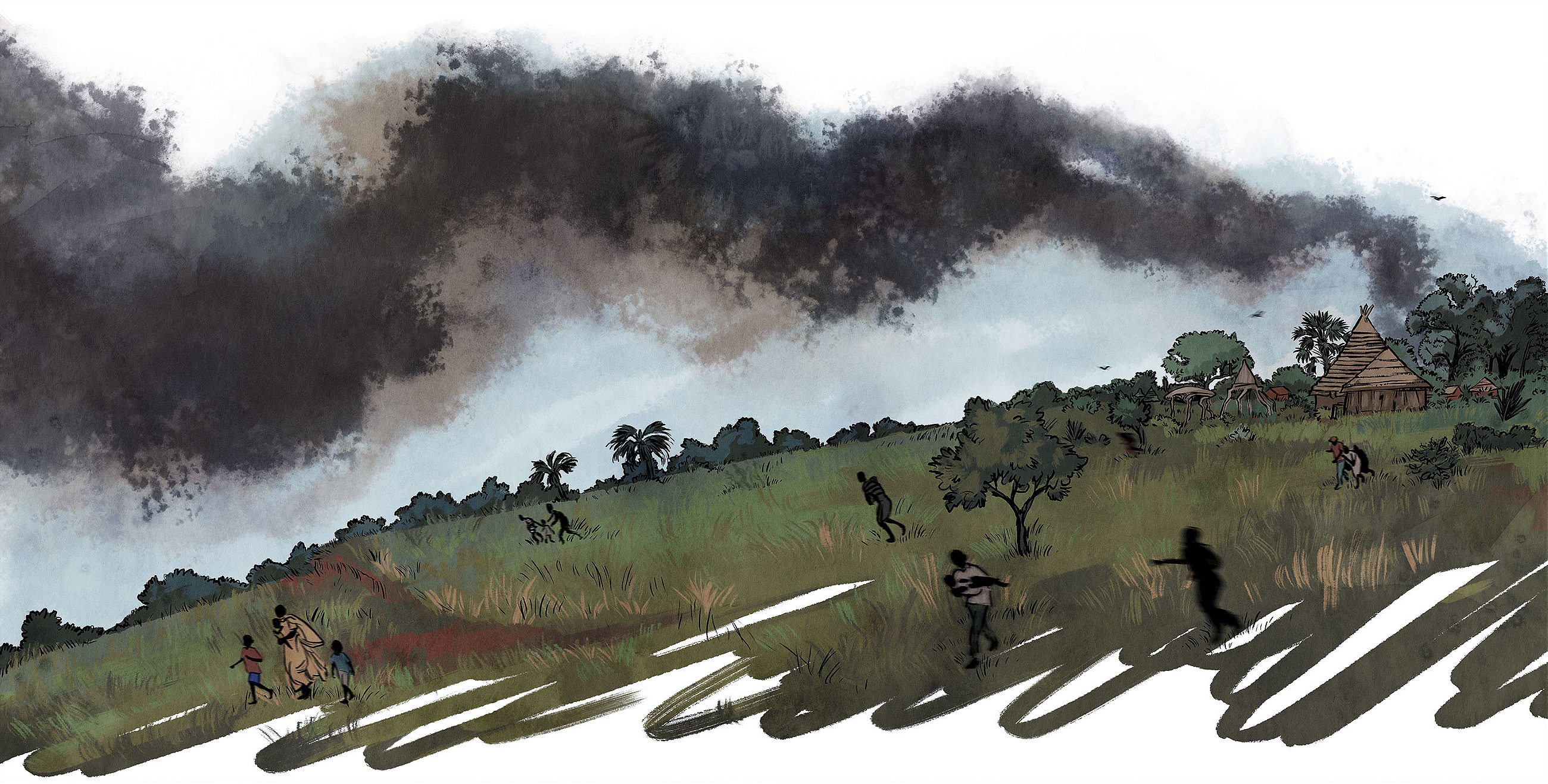

It was June 2016, and one week earlier, this had been ground zero of a devastating attack that displaced at least 30,000 people and as many as 150,000. Wau, one of South Sudan’s largest trade hubs, had become the latest victim in the country’s civil war. Initial government reports blamed the attack on a coalition of Darfuri paramilitaries and Joseph Kony’s LRA and put the death toll at 42. An official fact-finding commission later admitted the number could be higher.

Eyewitnesses, now huddled in camps around town, told me a much different story. They recounted door-to-door executions and bodies lying in the streets, left out in the sun. They said the culprit was the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, the guerilla force that became the government army when South Sudan achieved independence in 2011. Wau had become the latest victim in a civil war that began in 2013, when a political spat between President Salva Kiir and VP Riek Machar turned violent, sent Riek into the bush, and fractured the country along ethnic lines. To date, nearly 400,000 people have been killed in the ongoing conflict.

I landed in Wau a few days after the attack to report on the humanitarian situation and found the town paralyzed. The main streets bristled with soldiers and large swathes of town were entirely deserted. Many people fled to the UNMISS base but were refused entry to the fortified compound. They were forced to pitch camp outside the perimeter, protected by little more than knee-high barbed wire. (A year later, peacekeepers in Wau would face sexual abuse allegations.) Others ran to churches and schoolyards. The less fortunate were forced into the bush, where they were subject to army raids and tropical diseases.

By chance, I’d met Sister Gracy at one of these church camps soon after I arrived. She, along with church leadership, was heading up food distributions for the tens of thousands of people who’d taken shelter at churches across town. She’d been planning to take her triennial trip back home to India to seek medical treatment for a chronic heart condition and see her aging mother. But after the first shots were fired, she cancelled her flight and unpacked her bags. There was work to do.

Right away, she took me in. I was of south Indian descent and she saw much of her own nephew in me. We were almost the same age and shared the same mop-headed haircut. Over the next few weeks, I lived by her side as she did the best she could to hold the church camps together. All her young volunteers had flown back to India as soon as the fighting began, and she was happy to have company again.

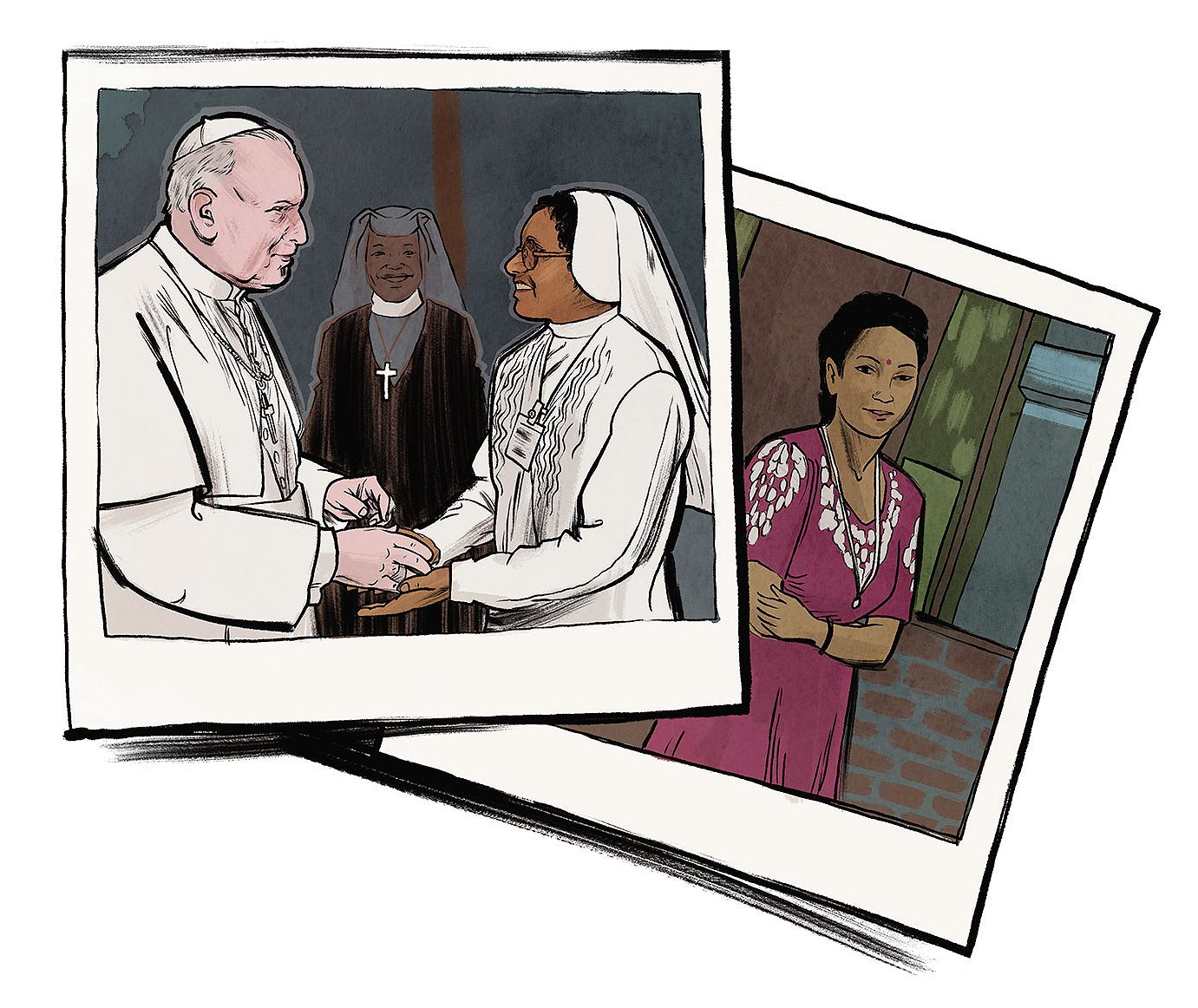

Sister Gracy Adichirayil was a nun in the Salesian order, a Roman Catholic institute founded in 1872 tasked with serving disadvantaged children around the world. She had come to Sudan 30 years ago, when civil war pitted the government in Khartoum against the southern SPLA insurgency. Despite chronic instability, she managed to build several schools, a nursing college, and a hospital. She taught thousands of children and found homes for hundreds of orphans. Along the way, she’d become something of a fixture in Wau. Wherever we went people called her by name, or called her uktana. Our sister.

But for all her work, she’d fallen afoul of her superiors in Rome for going beyond the provincial mandate of the Salesian Sisters, namely, elementary education. And it seemed that no matter how much she worked, a surge in violence would bring things back to square one. In some ways, the attack in Wau was a test of her resolve.

Throughout South Sudan’s tumultuous history, people like Sister Gracy, embedded in their communities and devoted to them, have done their best to hold on as best they can. She’d been through it all: the wars, the death threats, the deportations, and the peace deals that continue to precariously tie a tattered nation together. Her faith and her stubbornness had carried her through. But now, things were different. Her health was flagging, her congregation was nearing the end of their line, and the situation in South Sudan was showing little hope.

She was also faced with an ultimatum, handed down by her superiors in Rome, to choose between South Sudan and the Salesians. She was forced to ask herself if, after 30 years, she’d made a difference, and whether she was truly doing the Lord’s work. It was a question that laid bare the truth of doing the right thing: that it is not a single decision but a constant, often painful process, with no easy answers.

“The soldiers can’t stop me,” she told me. “I used to be their teacher!”

The June 23 attack was unexpected for Wau, which had been spared the worst of the war. It was also a test for South Sudan. A year earlier, things were looking up: Kiir and Machar had signed a peace deal. And in April 2016, Riek had returned to Juba, South Sudan’s capital, to take up his post in the unity government. But cracks showed early on. The president unilaterally redrew state boundaries, violence continued unabated in certain regions, and several officials in Juba were assassinated. It was uncertain just how long the peace deal would last.

Curiosity was getting the better of Sister Gracy on our drive. She wanted to see just how hard Wau had been hit. She turned to cut through Nazareth Quarter, which received the brunt of the attack. Like most of the worst-afflicted parts of the country, Nazareth was predominantly made up of ethnic minorities that had fought on the “wrong” side of South Sudan’s long battle for independence, that is to say, against the Dinka-led SPLA. This was score-settling. That the military hadn’t been paid in months provided a trigger for a decades-old animus.

As we passed through the wreckage, Sister Gracy told me how she’d driven through the shooting a week earlier to rescue Dennis, one of her assistants. She sped across town without concern for her safety. “The soldiers can’t stop me,” she told me. “I used to be their teacher!”

“If I have, I give.”

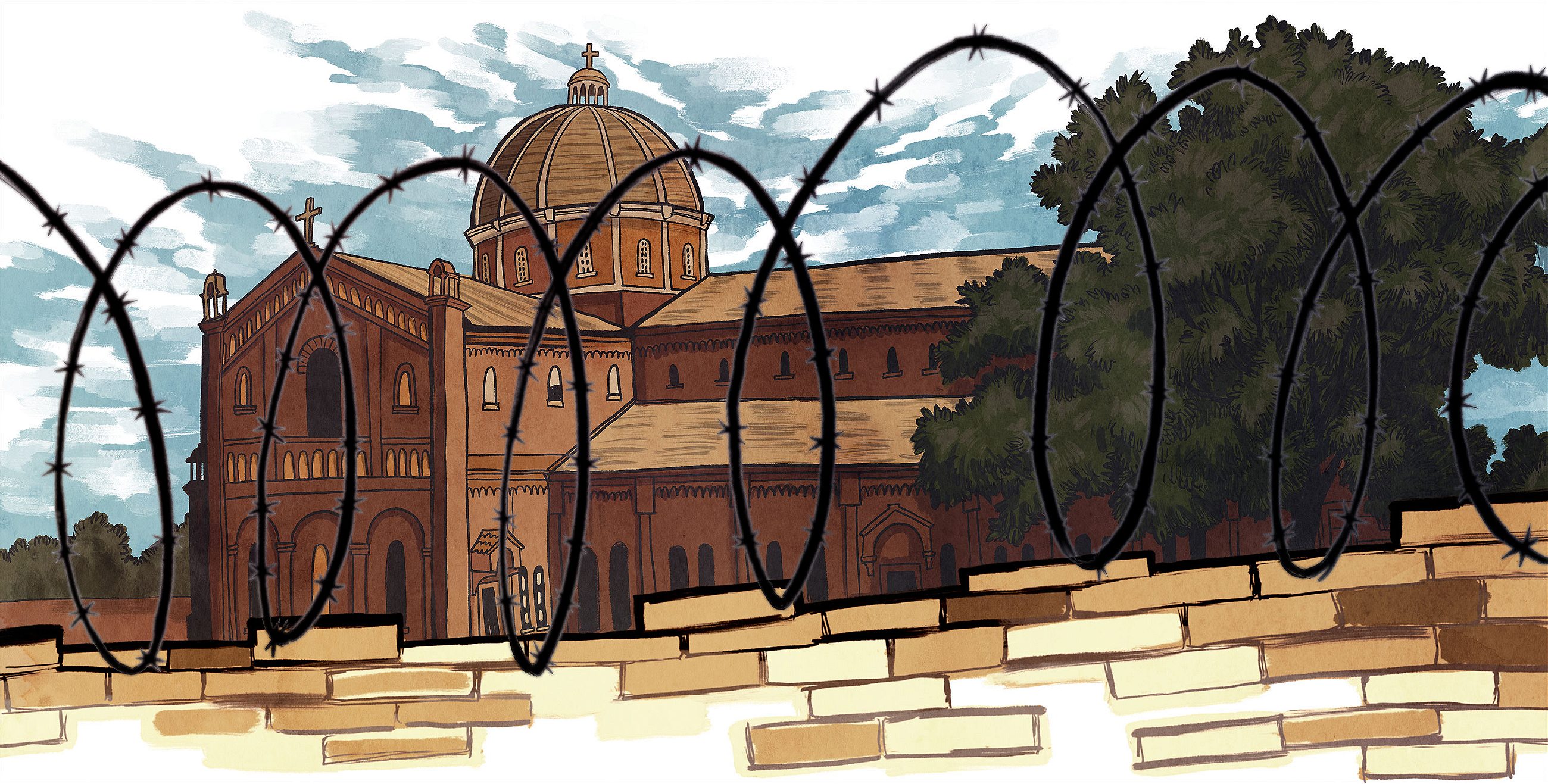

St. Mary’s Cathedral sits in the heart of Wau, a landmark for locals. Its tall brick dome rises high above the low-slung colonial-era buildings and tin-roof shacks around it. For decades it was the tallest structure in Wau, until a mosque was built on a nearby hill in the 1980s. Inside, turquoise columns and dark pews cut a path to an ornate gold altar watched over by a sculpture of Mother Mary, arms stretched open. “More beautiful than it has any right to be, no?” Sister Gracy asked when she caught me staring at it one afternoon, as we made our way through town.

She often turned her statements into questions, with a “But you already know this” sort of lilt in her voice. Sometimes she threw in a wink—“just between us.” She knew how to use it to her advantage, persuading UN officers to lend construction equipment or finding common cause with soldiers that tried to give her trouble. When I said that she seemed able to convince anyone of anything, she refused credit. She insisted, “When there’s something I want, Mother Mary goes before me and makes it easier.”

But some well-intentioned mischief and a white lie didn’t hurt either. Once, when the bank refused to let her withdraw cash, she had me pose as a donor visiting from Germany, demanding answers, while she pretended to weep. I’d seen her feign anger, yelling in Arabic when some farmers had encroached on her school’s land, only to turn to me and wink afterward. Whenever things got to be a bit too taxing, too tiring, she hit the release valve—“Oh my Jesus!”

Just across from St Mary’s was the Diocese of Wau, where we made daily visits, checking in on the more than 10,000 people sheltering in the compound. Before the attack, uniformed school children would rehearse songs in the playground and clergy-in-training would discuss theology under the courtyard’s mango trees. But now, families commandeered classrooms and pitched their tarps on the dusty lot. NGO 4x4s ebbed and flowed through the lot, as did people returning from day-trips to their homes, or what was left of them. A market sprang up between the tents where young boys hawked cellphone credit and their mothers roasted corn, eking out whatever normalcy they could.

And by the front gates lay an impromptu cemetery. It held 14 graves, some for children just into their teens. The military, however, said the graves were those of rebel soldiers.

And by the front gates lay an impromptu cemetery. It held 14 graves, some for children just into their teens. The military, however, said the graves were those of rebel soldiers.

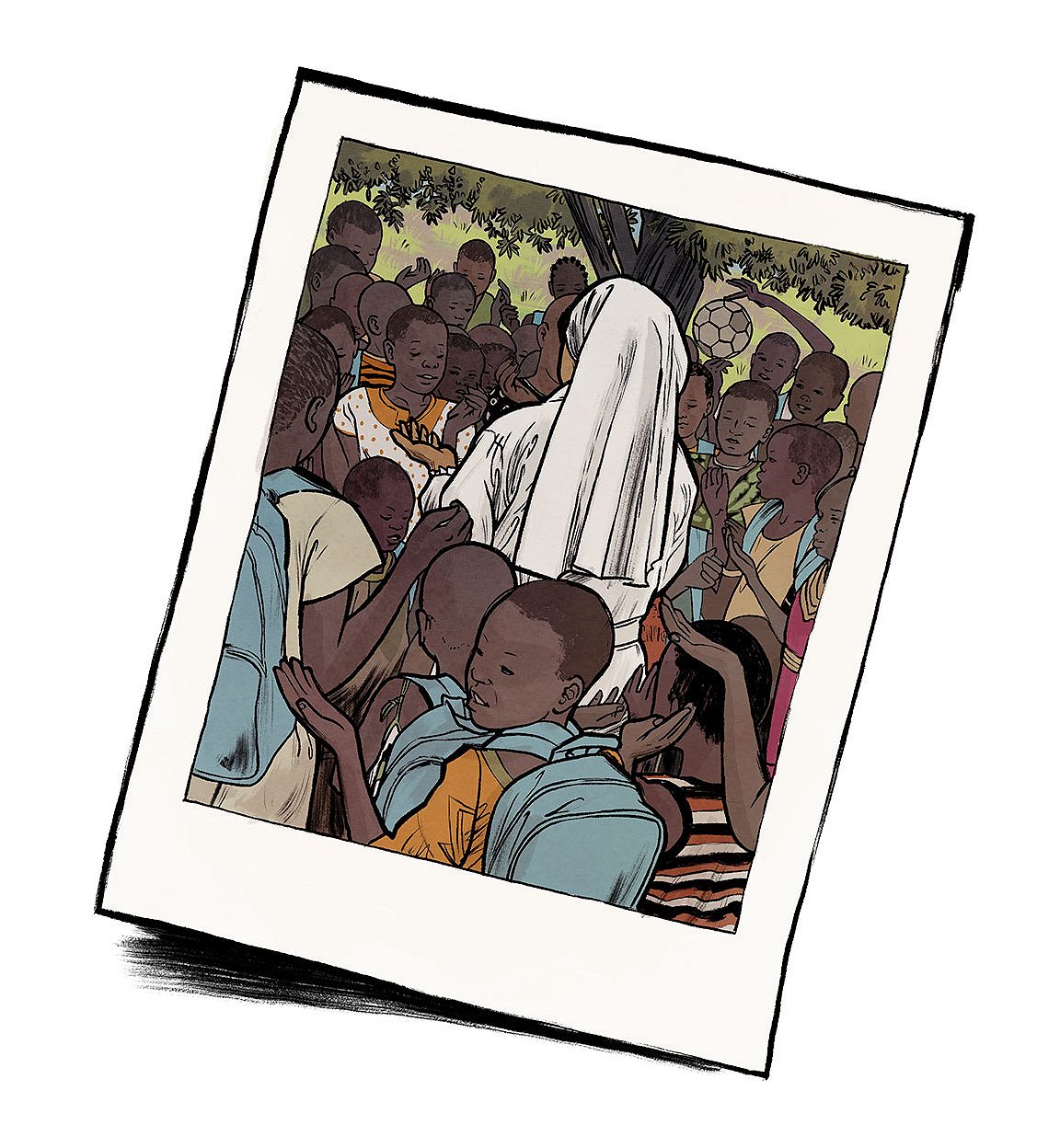

Sister Gracy ran point on food distributions at the compound, liaising between international NGOs and the Diocese. More than once, she dipped into her own funds and her hospital’s food stores to feed the growing camp. People often called out to her, “Uktana!” and asked for assistance. Maybe some food for their children, medicine for their grandparents, help to locate a lost relative. Sister Gracy would nearly always stop to listen, and direct a student or volunteer to see the request through. It also ensured that we ran perpetually late.

When they showered her with gratitude, she smiled uncomfortably and shoved her fists into the pockets on the front of her tunic. She did the same when she was trying to hide her frustration. Given the pace of life she lived, it was no wonder why all her pockets were torn.

I once asked how she decided when to give and when to say no.

She answered, “If I have, I give. No one asks unless they need, no?”

But it was rarely so simple. Take Sister Gracy’s malnutrition program, which offered regular diet supplements for more than 2,000 babies and their mothers. It’s a question at the heart of humanitarianism: do you feed the healthiest, who have the best chance of survival, or do you feed the weakest, who need the most help?

I thought that becoming a sister was the last decision I would have to make, but that’s just not so.

“These mothers come here looking miserable. They don’t wash or feed the babies. They know I’ll get angry with them. I’ve yelled at them so much. They think the only way to get food is by looking miserable. So I’m trying to only give food to those that keep their babies well.”

Sometimes it was impossible for her to tell whether she’d made the right choice. “I thought that becoming a sister was the last decision I would have to make but that’s just not so,” she recalled, laughing.

Missionaries in this part of this world have had a historically spotty record. Though they provided education and medical services, they were also an instrumental part of the imperial trinity, alongside the anthropologist and colonial administrator. Even recently, they have acted as vehicles for foreign intervention, informing on foreign governments, supporting white apartheid governments, and lobbying to restrict LGBTQ rights abroad.

Nevertheless, Christianity found fertile ground in South Sudan, especially during the 50 years of war for southern independence. When foreign missionaries were expelled by Sudan in 1964, locals were forced into leadership and are largely credited with the explosive growth of the faith in Southern Sudan. Church leaders, like Bishop Paride Taban, crafted peace agreements and led grassroots conferences that ended decades of inter-communal fighting. They even drafted pamphlets pleading for reconciliation and hand-delivered them to rebel leaders in the bush.

These local efforts and the American evangelical bloc were instrumental in ending South Sudan’s civil war in 2005 and paved the way for South Sudan’s independence in 2011. But just two years later, fighting would break out in the fledgling nation, wiping away decades of work by local churches and civil society.

One evening, Sister Gracy took me to see the children’s hospital she’d built. It was a two-story complex complete with a surgical wing, OB/GYN clinic, classrooms, and its own farm. As we drove around the property, Sister Gracy pointed out the fruit trees she brought from India, the rice paddy and vegetable garden her students planted. We parked beside a small pen with a fat, lonely, pig. “The volunteers and I were going to make a big thing and eat it but now they’ve all gone.” A silver lining for an old sow.

She showed me empty bookcases, dusty operating theaters, and bare-bones clinics. “We were only running for three weeks and now I’ve shut it down. People are scared to come to this side of town,” she said. To get to the hospital meant passing by the military barracks. Half of her hospital staff had gone missing after the attack and were as yet unaccounted for. We went up on the roof and looked out across the fields, once so carefully tended to, now pockmarked with weeds.

“I’ve seen young boys like you starving in the war, walking with sticks like old men,” she said, staring off. “I’ve had mothers give me their baby so they can die in my hands. I’ve seen misery here for decades. I never lost hope. But now, there are no easy solutions.”

The Road to Sudan

Early one morning we were woken up by the sound of artillery fire. “Oh, that? They’re only making trouble. Don’t worry. Just pretend it’s wedding drums,” Sister Gracy assured me. We would later learn that the SPLA had raided a small bush camp outside the city. Hundreds came to the Diocese that afternoon seeking shelter. They brought with them one more body, that of a young man who’d been shot in the head a week earlier and had finally succumbed to his injuries. He would be St. Mary’s 15th grave.

As I tried my best to ignore the distant explosions, Sister Gracy confessed, “I’m not feeling right.” It was the first time I’d heard her complain.

She revealed earlier that she suffered from a heart condition that left her leg swollen and tender. Her health had been deteriorating for years, but it was impossible to pull her away from her work. In 2012, the orders came down from Rome: go back to India and get treated. She complied. But after a short rest in a village home, she snuck back to South Sudan and wrote the Mother General a letter of apology.

But her leg wasn’t the source of her discomfort. “I’m not working. I’m not good at sitting,” she said.

I thought she was kidding. Every day, she woke up two hours before me to pray, coordinate food deliveries, and call around town to get the latest news. We would eat a quick breakfast before making the usual rounds: the Diocese, her children’s hospital, the market, the bank. We were on our feet all day, out in the scorching heat. I fell asleep as soon as we finished dinner while she stayed up a few more hours, handling paperwork and emailing donors.

Her uncle, a priest in Delhi, described young Gracy to me as “a monkey on a hot stone.”

But these were just ways for her to pass the time. Before the attack, her days had been packed: teaching classes, overseeing construction, visiting patients, managing her schools. But now, everything was shut down and many of her employees had taken to the bush in fear. If she could help it, she’d never sit down.

Sister Gracy had always been this way, long before she was in South Sudan, long before she was a sister. Her uncle, a priest in Delhi, described young Gracy to me as “a monkey on a hot stone.”

Sister Gracy was born in a small town in Kerala, India, where the apostle Thomas had ministered the Gospel 2,000 thousand years earlier. Charity ran in the Adichirayils’ blood. Her father, a well-off rubber farmer, built schools, roads, and clinics for the village. Her older sister Annie was a Salesian sister and nurse. Her uncle in Delhi ran a school for children living in the streets for the Don Bosco order, the Salesians’ male counterpart. Her older brother was known affectionately as “Saudi Babu”—he was a businessman in the Gulf, hiring people from the community and building homes for their families back in Kerala.

It was a spirit that seemed to infect Sister Gracy’s entire community, and she wasn’t afraid to use it. In 2017, I joined Sister Gracy on a visit to her village in India during one of her rare vacations. Her brothers, nephews, and more than a handful of neighbors proudly told me how they had volunteered for her in Wau as masons, teachers, and nurses. But they also rolled their eyes when Sister Gracy began telling stories about South Sudan. They’d heard it all a thousand times.

Growing up on her father’s farm, Sister Gracy spent a great deal of time with the laborers in the fields, women from the Dalit (formerly “untouchable”) underclass. She brought them water in the midday heat, helped them carry their harvests in the evening, and looked after the children while the mothers were out in the fields. “I was one of the only people they allowed in their huts,” she boasted.

When Sister Gracy was still in grade school, her older Sister Annie went off to northern India to join the Salesians. But a few years later, when she asked Annie how to become a nun, she was told, “Forget it Gracy, you will never become a sister.” She was too headstrong, too restless to be in a convent.

The dismissal only strengthened her resolve. Sister Gracy fired off a blunt letter to the convent in Assam state. “I want to become a sister. What shall I do?” The response from the provincial head read just as forthright. “Come quickly.”

And so she went, age 19, to a convent on the opposite side of the country. She was a star student and distinguished herself for her stoicism and courage. In 1987, when a bus toppled off a cliff on northern India’s tortuous mountain roads, Sister Gracy led the rescue mission. She also had a personal crusade to vaccinate every child in the state’s tribal areas. She recalled walking for hours a day, through forests thick with guerrillas fighting the Indian government, giving vaccines in every village along the way.

Sister Gracy was just one of many clergy in India committed to social justice during that time. Like Thomas Kocherry, a Catholic father who unionized fisherman in Kerala and turned down a $200,000 MacArthur “Genius” grant because Shell Oil, a well-known coastal polluter, was a sponsor. Or Arvind P. Nirmal, who adapted Liberation Theology to assert the humanity of the Dalit class and that Jesus was himself a Dalit.

When a fellow sister returned from Sudan with photographs of the desperate conditions in the camps outside Khartoum, Sister Gracy was deeply moved. When making her final vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity, she promised that “If Jesus calls me, I will go to Africa.”

But when the call came down from Rome a year later, Sister Gracy found herself feeling doubtful. She had found her stride serving the northern tribal areas and loved the villages in which she worked. She told her superior she wouldn’t go to Sudan, but was told to think it over.

“I stayed up, tossing and turning, for two days. I asked myself if I was doing it for my success or for Christ. That was when I really gave my life for Christ. If we give, we must give everything, not keep something for ourselves.”

She packed her bags and arrived in Khartoum on July 2, 1989.

An ultimatum

The Acts of Thomas, a non-canonical New Testament text, recounts the story of the Apostle Thomas’s mission to India. Shortly after the death of Jesus, the disciples gathered to cast lots to decide where in the world they would minister the Gospel. “Doubting” Thomas, the same who refused to believe that Jesus had truly risen until he touched Jesus’ stigmata, drew India. But true to his nickname, Thomas was apprehensive. So Jesus returned to earth, disguised as a slave trader, and sold Thomas to an Indian merchant. The merchant took Thomas to India to the court of King Gondophares, who upon learning that Thomas was a carpenter, ordered him to build a palace.

Thomas was sent away to begin construction and often wrote to the king asking for additional funds, which were obliged. But when the king came to see what Thomas had built for him, he found the site empty. Thomas had given all of the money to the poor and the needy. He told Gondophares that he had built the palace in heaven, that “When thou departest this life, you shall see it.” Thomas was, predictably, thrown in prison.

The work of the missionary in South Sudan was, aside from being uninvited, similarly thankless. Throughout Sudan’s history, missionaries have been regularly harassed, kidnapped, or killed. On the one year anniversary of Sister Gracy’s arrival in Khartoum, the small church she’d helped build and manage in the camp was burned down by Sudanese soldiers. It was an early lesson of life in war.

“All that I did for one year. One second later, under fire,” she said. “But as I cried, [the people in the camp] told me, ‘Sister, Allah Karim. God is Great. If he provided for us today, he will provide for us tomorrow.’”

On a particularly slow night, she dusted off an old photo album. It was tidy and meticulous, each photograph labeled with a printed slip and glued perfectly square. The first page held the very same images of the camps outside Khartoum that inspired Sister Gracy to come to Sudan in the first place.

When she was transferred down south to Wau in 1998, after serving in the Khartoum camps for ten years, she found the situation even worse. SPLA infighting and a government clampdown on aid relief left civilians squeezed on all sides. The government attacked civilians sheltering in hospitals and camps, sparing only the Diocesan compound. Mass graves dotted the city. Famine put 250,000 people at risk of starvation.

The faded, grainy photographs showed a much younger Sister Gracy kneeling beside young children, administering medicine and handing out nutritional supplements. She looked over nearly 5,000 children, nearly 300 of whom were orphaned. Even twenty years on, she could still name them through the faded photographs and recount which families took them in. As she turned the pages of her scrapbook, the skinny children sitting nearly naked in dirt courtyards, fleshed out, putting on weight and new clothes.

Despite Wau’s instability, Sister Gracy started constructing St. Joseph’s primary school. It started out as an informal outdoor program, with 250 kids in each class. Quickly, the school took on brick walls and tin roofs, chairs, and desks. She beamed with pride as she recalled the day the children received uniforms. “The happiness of the children! You can imagine. And how proud they walked!”

However, the Salesian leadership was concerned that resources were being poured into something that could be swept away by the next battle. “I was in a lot of trouble and always at odds with the leadership. After I finished St. Joseph’s, I came back into their good book.” She promised not to repeat the mistake. “But in my heart, I knew if the situation came I would do the same.”

Then she started building a nursing college. “Salesians are focused on primary and secondary education, but in a place like South Sudan, you must provide other services. And there is no one here to provide healthcare.”

She secured piecemeal permission from her superiors, writing back every few months, like Thomas, to stretch her vision. “You can call it updating goals, but I knew what I was doing,” Gracy said. She showed me proud photos of her first graduating class of nurses, now working all over the continent.

But the college far exceeded the mandate of the Salesians and was a financial and logistical burden they did not want to bear, especially given Sister Gracy’s health. As a stopgap, Sister Gracy handed off the college to an NGO co-signed by her older brother and a priest in Kerala. Mary Help of Wau, as it was called, allowed Sister Gray to fund her projects independently, but with the express permission of the Bishop of Wau.

For the next five years Sister Gracy did her best to stay in tract. “But these nurses needed to have practical training, so we needed a hospital.” She turned to photos of her students practicing on patients under mango trees in an open courtyard. She quietly started planning her magnum opus: The Mary Help Maternal and Child Friendly Hospital.

She raised a small army of allies to realize the vision. A former governor granted the land, the Chinese UN contingent offered sand and built the road, and Indian volunteers provided the labor. Bricks were cut from a quarry on the property and metal fixtures were made by local welders. She paired with German donors and Catholic NGOs to fund the project and ship in supplies.

I took a vow of obedience but did not obey. I took a vow of poverty but I have handled a lot of money through the NGO.

When the former governor of Wau visited the site, he told Sister Gracy, “I wish we had taken all the money we spent on guns and put it here.” She recalled him asking the health ministry, “If Sister Gracy can do all of this by herself, what are you doing?” During the June attack, that governor, known for speaking out against military abuses, was arrested and imprisoned.

For the congregation in Rome, however, the hospital was the last straw. They delivered Sister Gracy an ultimatum: Leave the Salesian order or leave South Sudan. It didn’t come entirely as a surprise.

“I took a vow of obedience but did not obey. I took a vow of poverty but I have handled a lot of money through the NGO. I don’t blame the Mother General, I do not blame anybody.” She paused for a moment and smiled. “At least, I know I am perfectly practicing chastity.”

Others in Wau were less forgiving of the situation the leadership had put Sister Gracy in. “When big people make a mistake, they don’t want to accept it. So they throw it under the carpet and people like Gracy become victims,” Fr. James Pulickal, an Indian Don Bosco missionary in Wau, told me. “See, there is this apartheid thinking. They consider anything that is not white as shit.”

“In every congregation, there are these vibrant people. You can’t smother them. Some surrender under the pretext of obedience. Only Gracy had the guts to say ‘rubbish’. For some, she is a saint,” Fr. James said. “For others, she is [a] rebel.”

When I called the Mother General’s office in Rome—which oversees the work of over 13,000 nuns worldwide—to ask about a “sister in South Sudan”, they knew right away who I was referring to. However, they declined to comment on their relationship with her.

Nevertheless, the Salesians had always been family to her. It was the order of her uncle and her older sister. Leaving the congregation was almost unthinkable. But leaving South Sudan, where she’d been for decades, was just as distressing. She always thought she would be buried in Wau.

Mother Teresa had found herself in a similar situation with the Loreto congregation exactly 70 years earlier. The Loreto mandate was strictly devoted to education and rarely allowed sisters to serve outside the convent. So when Mother Teresa felt her calling to live and work among the poorest in Calcutta, she had little choice but to ask to leave the congregation and strike out on her own. Sister Gracy hadn’t ruled out the option.

“To pull the plough and look back is not worthy of the Kingdom of God. Is my plough my congregation or my work here? Am I doing God’s will or am I doing it for myself?” She fought back tears. “I don’t know. God will show me the way.” She closed the scrapbook and put it back in her closet.

And that was the brutal truth of Sister Gracy and the part that lingered with me for years afterwards. She tore away all the excuses and contortions hiding the simple fact that “doing the right thing” takes sacrifice. It was a terrifyingly honest way of life that left little to hide behind. But it also gave me an example of what “righteousness” (and not in the pejorative sense) could look like.

Sister Gracy put others before her own safety, health, and comfort. That was the easy part. What wasn’t so easy was that the whole endeavor, her entire mission, hinged on faith. There was no way of telling whether she made any difference at all. Sister Gracy could never expect to see herself vindicated, especially in a place like South Sudan.

That was the brutal truth Sister Gracy wrestled with every day, and one that only outsiders like myself could find any comfort in: that the people who tear themselves to pieces trying to figure out whether they’re doing the right thing, often are.

The following night we learned that the unity government in the capital had fallen apart. The Presidential compound was attacked, Riek Machar’s home was bombed, and Juba had become a battlefield. When fighting approached closer to Wau later that week, we would evacuate aboard a 12-seat prop plane. We shook hands and transferred flights at the Juba airport. I would fly to Kenya, and Sister Gracy would fly to India, to take her long-delayed vacation.

“We always finish what we start.”

I returned to Wau in June 2017, almost one year to the day since the attacks. I had come to see how the town had fared since the peace deal’s collapse, and to check in on Sister Gracy, who was waiting for me at the side of the airstrip. “You’ve grown out your beard. Have you joined the Taliban?” She laughed and loaded me up in her trusty Landcruiser.

Things were steadily improving, she explained as we made our usual rounds. And sister Gracy had returned to that 5 a.m. to 11 p.m. schedule in which she felt at home: teaching at the university, running her nursing school, managing her hospital, and overseeing her primary schools. She’d even brought along two of her nephews and another nurse from India to help her.

But it hadn’t been entirely smooth sailing. The failure of the peace deal encouraged a spate of enterprising rebels to carve out ethnic fiefdoms, making peace even more elusive. Violence had almost entirely emptied the southern belt of civilians. Today, another tenuous power-sharing agreement is in place and on the rocks, co-signed by an alphabet soup of rebel groups. Still, aside from an attack in April 2017 which killed 16 people, Wau town had fared better than most.

Despite the improved security, tens of thousands of people remained in protections sites across town. The camp provided the Diocese with much-needed resources from international NGOs, and there was little affordable food to be had outside. It was upsetting for Sister Gracy, who preached self-reliance. “If the NGOs said they would give food, but you don’t need to stay in the camp, most would go to their homes,” she said. “But if there is no camp, there is no food. And if there is no camp, there is no money.”

In that spirit, Sister Gracy took me and her nursing students to work the fields around the St. Mary’s Hospital, now back up and running.

We worked double duty: planting cassava root and distributing food for the 400 mothers in Sister Gracy’s infant nutrition program. The mothers also received cassava root and careful planting instructions. Sister Gracy was in her element, handing out orders, rolling up her sleeves, checking in on the farm, the clinic, the classrooms. All her fears about the ultimatum looming before her and the precarious state of the country seemed distant. She’d bought a bit of time from the Salesian leadership, promising to find another congregation to take over her projects.

She traveled up and down Kerala to find one. But whenever one or another stepped up to the task, Sister Gracy would demur. “They’re just not ready,” she would say. She seemed to still be waiting for God’s guidance, staying in South Sudan as long as she could while still trying to remain obedient to the Salesians.

(When I spoke to her on the phone in November 2019, she told me that she had found a promising congregation to manage her hospital. Earlier this spring, five young sisters from Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, arrived in Wau to start their trial run.)

After a long day in the unrelenting heat, the evening rains were a welcome relief. We looked forward to sleeping in the cool air that night. Maybe we’d even get to sleep in.

Sister Gracy’s nephews shuttled mothers and students home in the Landcruiser. As we waited for the car to return, we took shelter in a small shack beside the hospital. Sister Gracy saw me soaked and shivering. “Do you want some tea?” she asked.

We crouched by the stove and set about trying to light it. We took turns blowing on a single chunk of coal, fanning it with cardboard, torching it with crumpled newspaper. Despite our best efforts to coax a steady flame, the coal remained less than compliant. By then, the rain had let up and the car had returned. Her nephew stood behind us, amused by our efforts. After 15 minutes of huffing and puffing, the coal finally glowed red.

Sister Gracy stood up, satisfied, and brushed her hands on her dusty tunic. She snuffed out the stove with a pot of water and made for the car. “Had your fun?” I asked, teasing.

“We always finish what we start.”

She jingled the keys, gave me a wink, and just like that, we were on our way. Running late as always.