Ice cream, pretzels, beer, plus Ethiopian wat (with karaoke!). Here are the 10 dishes that make Philly.

Philadelphia’s cuisine tells the story of an underdog city built on the hard work of immigrant communities. Most Philadelphia fare was born from resourcefulness and frugality, and food that nourished the city during pivotal moments in history. The Pennsylvania Dutch helped to feed America’s rebel-rousing Founding Fathers as they challenged England to war over independence. During the 19th century, industry was fueled by Italian laborers who not only worked in the factories but planted the seeds of what we now know as Italian-American cuisine. Even today, new waves of immigrants continue to deepen the Philadelphia foodscape, adding complexity to our cuisine and culture.

Pretzels

The history of the pretzel does not begin in Philadelphia, but pretzel-making in the city helped pioneer large-scale pretzel production and empowered entrepreneurship for generations of immigrant street vendors. America’s first pretzels migrated across the Atlantic in the 1700s with the Pennsylvania Dutch, a group of German-speaking immigrants, many of whom were Mennonite and Amish.

Their popularity can be credited to Daniel Christopher Kleiss, who began selling pretzels on the streets in the 1820s. But it wasn’t until the 1920s that the Philadelphia pretzel was born, leaving behind the three-holed pretzel shape representing the Christian trinity and taking on the distinctive figure-eight.

It was an Italian-American family who developed the first Philadelphia pretzel. The Nacchio family owned an Italian-American bakery, where the matriarch of the family, Maria, baked soft pretzels using a secret family recipe. Seeing how pretzels were growing in popularity in Philadelphia, her son, Edmund, created the Federal Pretzel Baking Company after importing a German machine. The new automated machine moved hand-twisted pretzels through a conveyor belt system that both soaked and baked pretzels, which resulted in sheets of soft pretzels that were easy to distribute widely throughout the city by street vendors, many of whom were immigrants starting a new life in Philadelphia. Today, one of the largest Philadelphia-style pretzel companies is the Philly Pretzel Factory, the company responsible for distributing the renowned soft pretzels from Long Island to Florida. You can find them at a Philly Pretzel Factory location, or from most street vendors operating out of metal carts on most city streets.

Scrapple

Scrapple is a hotly contested breakfast meat in Philadelphia. Made from scraps of pork (and sometimes cow) that can’t be used in other products, scrapple is a loaf of mystery meat that people either revere or detest.

Scrapple was brought to the Philadelphia region as early as the 1600s by the Pennsylvania Dutch. The dish, which stems as far back as pre-Roman times, was a way to repurpose scraps of meat and reduce waste. Skin, hooves, livers, snouts and any other undesirable parts were cooked down and thickened with cornmeal and flavored with salt, pepper, and herbs. The result was a firm loaf that could be sliced up and fried. It was a quick hit during colonial times, and by the end of the Revolutionary War, scrapple, as it became known to be, became a cornerstone in Mid-Atlantic cuisine.

Both George Washington and Benjamin Franklin were said to have enjoyed more than their fair share of scrapple during their years in Philadelphia. During a visit in 1860, Edward VII of England, then still the Prince of Wales, proclaimed it “a rather delicious native food.” Today, scrapple is served as a breakfast meat at most diners in the area, and can be purchased by the loaf in the Reading Terminal Market.

Ice Cream

Philadelphia’s deep relationship with ice cream has made it a center of ice cream innovation. It was a favorite dessert among colonists, and especially popular with America’s Founding Fathers. George Washington reportedly spent $200 ($5,000 in today’s money) on ice cream in a single summer, and Thomas Jefferson had his own 18-step ice cream recipe that he had learned from the French. The popular flavors at that time weren’t strawberry or chocolate, but savory ones such as oyster, which were a plentiful resource in Philadelphia’s Delaware River.

During the late 1700s to mid-1800s, several innovators in Philadelphia revolutionized ice-cream making, and it became an industry in itself. It began with Emanuel Segur, a Frenchman who began teaching Americans how to make French-style ice cream. From there, Augustus Jackson, a former White House cook, developed recipes for commercial use. Because many French-style ice cream recipes required egg yolks, a chemist by the name of Mary Engle Pennington taught producers how to safely make ice cream. And in 1843, Philadelphian housewife, Nancy M. Johnson filed the patent for her hand-crank ice cream maker—a design still used today. These advances transformed ice cream from a delicacy enjoyed only by the elite to a treat accessible to the average American.

Related Reads

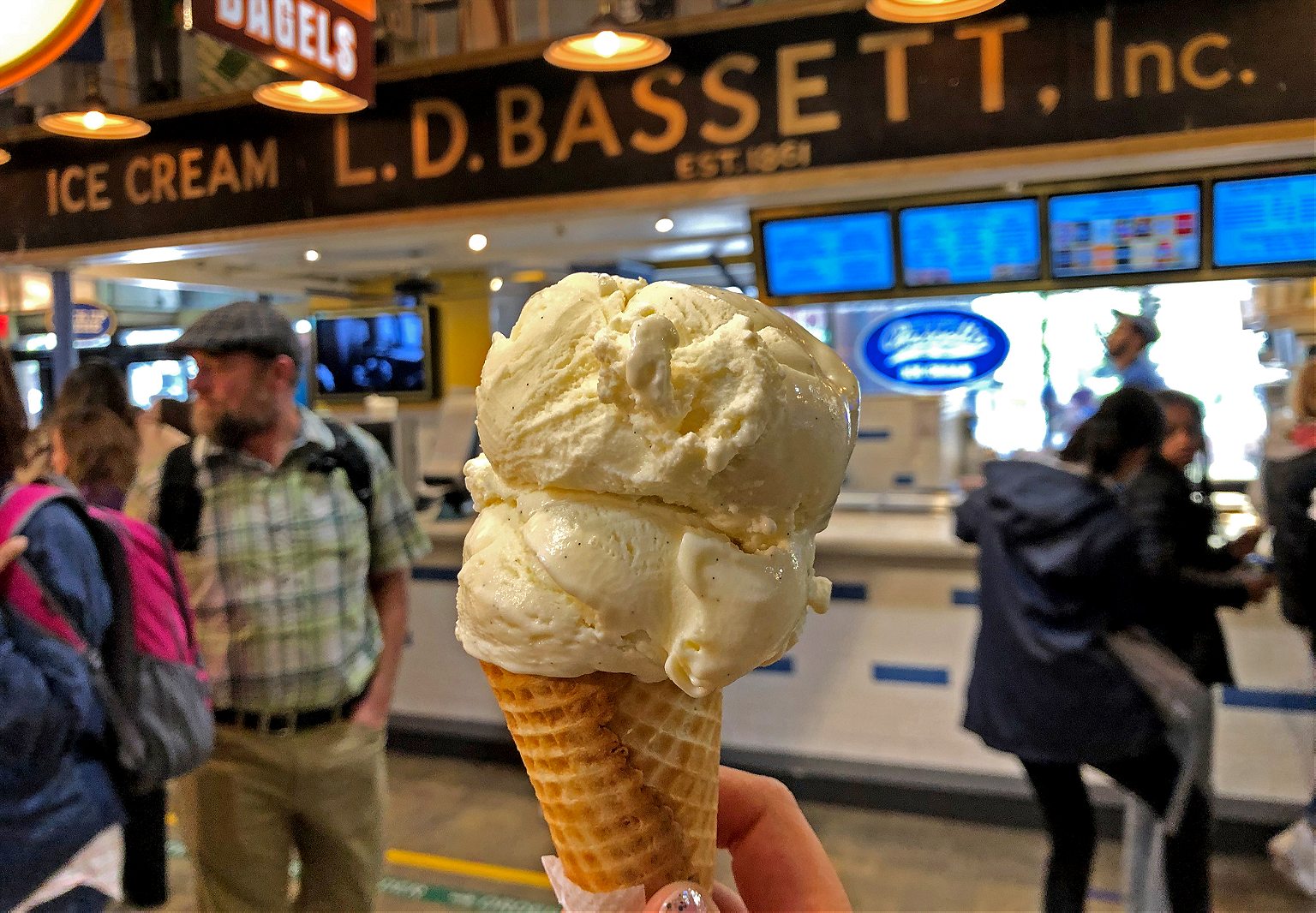

By the 1860s, Philadelphia was the leader in ice cream production in the United States. Bassett’s Ice Cream located in the Reading Terminal Market started in 1861 and is still the oldest existing ice cream parlor in the United States. Breyer’s Ice Cream was also headquartered in Philadelphia, from 1866 until they left in 1993.

The Philadelphia-style refers to an eggless variant to the French and New York styles of ice cream. Though Philadelphia-style can mean ice cream that is flavored with fruit, it also refers to a vanilla ice cream that uses vanilla bean instead of egg custard. During the 1800s, people would often seek out ice cream with specks of black vanilla, because it signaled to them that it was a purer product. History is blurry about whether Philadelphia-style ice cream originates in the city, but the city has been serving it continuously since Bassett’s opened in 1861.

Lager Beer

The word lager comes from the German word lagern—to store. It describes the slow-and-low method of fermenting, where the lager is stored in a cold cellar for prolonged periods of time. The method dates back to Medieval times, but it was perfected in Bavaria during the 1700s, around 200 years after the German Beer Purity Law (the Reinheitsgebot) limited beer making to four ingredients: water, hops, barley, and yeast.

As Bavarian lagers became known for consistency and quality, there was interest in bringing lager beer production to America. In 1840, John Wagner, a Bavarian brewer, brought lager yeast across the Atlantic Ocean, a tricky mission, considering how challenging it is to keep lager yeast alive. Wagner could brew a limited amount of lager beer from his home, but was never able to open a large-scale brewery. But with a large population of Germans living in Philadelphia, it didn’t take long for the demand for lager to grow and for ambitious brewers to seize the opportunity. By the 1850s, at least thirty breweries were producing lager beer, many of which were in the Brewerytown neighborhood.

The lager tradition carries on in Philadelphia as well as the rest of the state of Pennsylvania. Order a lager at most Philly bars and the bartender will hand you one from the oldest operating brewery in the United States: Yuengling.

Cheesesteaks

Perhaps most renowned Philadelphia dish, the cheesesteak is a long Italian roll stuffed with thinly chopped strips of steak, covered in a cheese adhesive holding the sandwich together. It has become a legendary part of the Philadelphia zeitgeist, thanks to a long-held rivalry over whose cheesesteak is best. This rivalry brings food-seeking travelers to where it all began, to the corner of 9th and Passyunk, where Pat’s and Geno’s are located.

The story of the cheesesteak begins in the 1930s, at a hot dog stand run by Pat Olivieri. One day, Olivieri, tired of having hot dogs for lunch, put grilled beef on a roll. As he finished assembling his meal, a cab driver, who had caught a whiff of Olivieri’s steak sandwich, asked if he could have some. Olivieri split his lunch with the cab driver and it didn’t take long for the rumor spread to spread that Olivieri had an irresistible new sandwich. Eventually, Olivieri opened Pat’s King of Steaks on 9th and Passyunk. In the 1940s, Pat’s manager, Joe Lorenza, added cheese to the mix, creating the infamous cheese steak.

The intense but friendly rivalry began in 1966 when Joey Vento opened a cheesesteak place across the street named Geno’s. In an interview with Philadelphia Magazine, Vento credited Olivieri for inventing the cheesesteak, but said: “All I did was come along and perfect it.”

Stromboli

The foundation of Italian-American cuisine is built on the Southern Italian staples of tomato sauce, cheese, olive oil, and breads. Italian immigrants, mostly from Naples, had their influence on the cuisine as well, but for the most part, what we know as Italian-American cooking comes from the kitchens of Sicily. During the 19th and 20th centuries, Italian immigrants moved to American cities for factory jobs, and with those jobs came the need for quick and portable meals made with simple ingredients.

The Stromboli was created in 1950 by Nazzareno Romano of Romano’s Pizzeria. He was experimenting with different kinds of “pizza imbottito” also known as “stuffed pizza” when he took ham, cotechino salami, cheese, and peppers, folded it all into a bread dough pocket, and baked it to perfection. A few variations exist within the region, such as the sauce-filled calzone and the deep-fried panzerotti, all of which are examples of how Italian-American culture has blended into the region’s culinary traditions.

Hummus

The Jewish community has had a presence in Philadelphia as early as the 1650s, earlier than William Penn’s arrival in 1682. Jews from Eastern Europe and Russia have been an integral part of Philadelphia’s food scene, opening diners and delis selling Ashkenazi staples such as hot pastrami, whitefish salad, and matzo ball soup. But Israeli Jewish cuisine, a culinary tradition drawing from Mediterranean and Middle Eastern influences, is redefining itself in Philadelphia, thanks to James Beard Award-winning chef Michael Solomonov. In 2008, Solomonov and his financier, Steven Cook, opened Zahav, adding Israeli dishes such as salatim, halloumi, and hummus to the Philadelphia foodscape. A few years later, the duo, listening to the demand for Israeli hummus, opened Dizengoff, a hummusiya that serves several styles of hummus and fresh pita bread in the Israeli tradition.

Ethiopian Wat

From 2000-2016, the fastest-growing community to immigrate to Philadelphia were African-born, with one of the largest groups coming from Ethiopia. During the 1970s and 1980s, Philadelphia accepted Ethiopian refugees fleeing the Dergue regime and the war with Eritrea. Many still immigrate to Philadelphia through family reunification, which allows refugees to resettle where they already have kin. This has resulted in a concentration of Ethiopians in the West Philadelphia neighborhood, where many have opened Ethiopian restaurants, grocery stores and spice shops selling high quality ingredients such as Berbere spice and injera.

Related Reads

Ethiopian cuisine is marked by wat, a thick stew of either vegetables, lentils, or spiced meats. Traditionally, several types of wat are served on top of the staple sourdough flatbread, injera. No utensils: diners use their right hand to tear pieces of injera and use it to scoop bites of wat.

Ethiopian food has blended into the West Philadelphia lifestyle. Dahlak Paradise has been operating for over 30 years and hosts a popular weekly karaoke party. Go upstairs at Abyssinia and you’ll find an unmarked speakeasy called Fiume, where you can pair Ethiopian wat with classic American cocktails. Rift Valley Grocery Store imports Ethiopian goods for anyone craving the aromas and spices of Ethiopian fare.

Polish Kielbasa

Polish communities had been migrating to Philadelphia since the 1750s, but many came during the early 20th century, when the ship-building industry was booming in the Port Richmond neighborhood. The neighborhood’s Polish cultural identity remains intact, with small businesses, clubhouses, and restaurants carrying on their traditions. Throughout the year, the neighborhood holds Polish festivals where visitors can experience traditional folk dances, indulge in babka, and snack on kielbasa.

Several Polish restaurants and smokehouses continue to specialize in the old-world techniques of preparing kielbasa. Czerw’s, a family-run smoke house that has been operating for over 75 years, continues to use traditional brick ovens built by the family’s patriarch, who immigrated from Poland in the 1930s. Swiacki Meats has been making kabanosy, kielbasa’s thinner, beef jerky-like cousin, since the 1950s.For a taste of Polish hospitality head to Syrenka Luncheonette, where you can enjoy traditional kielbasa along with other Polish staples such as pirogies, stuffed cabbage, and bigos.

Bibimbap

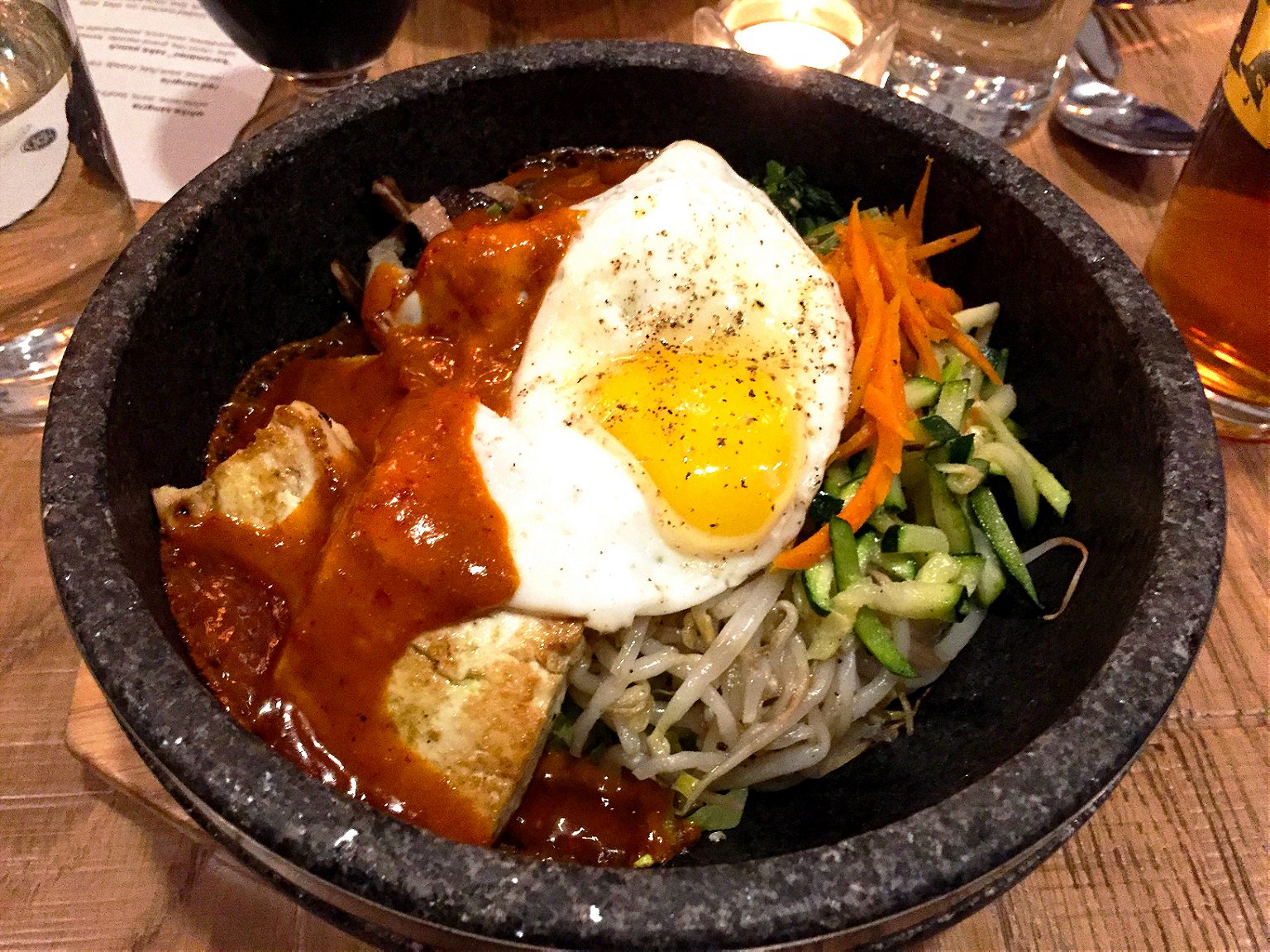

Philadelphia has seen many different immigrant groups who came to the city for many different reasons. For Korean families, it was a chance to pursue entrepreneurship, to send their children school and to seek a new life after the Korean War. When the U.S. passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which lifted the limit of how many Asian immigrants could come to America, Koreans seized the opportunity. They quickly became one of the top 10 new immigrant groups in Philadelphia only five years after the act passed. Though Philadelphia had a well established Chinatown that had been a safe haven for Asian communities who immigrated to the city, the Korean population began settling their own communities. By the 1980s, the Olney section of the city became known as Koreatown, which has become a culinary destination. Between restaurants and H-Marts, Philadelphians have access to the best that Korean cuisine has to offer. And one of the best Korean staples is bibimbap.

Bibimbap is a well-rounded comfort food: hot rice topped with a variety of vegetables, sliced meat, and a runny egg. It can be served in a regular bowl or a hot stone bowl as a Dolsot-bibimbap. It was a dish traditionally eaten on the lunar new year’s eve, to finish leftovers so as not to bring old side dishes into the new year. Now, bibimbap is a dish for any occasion.