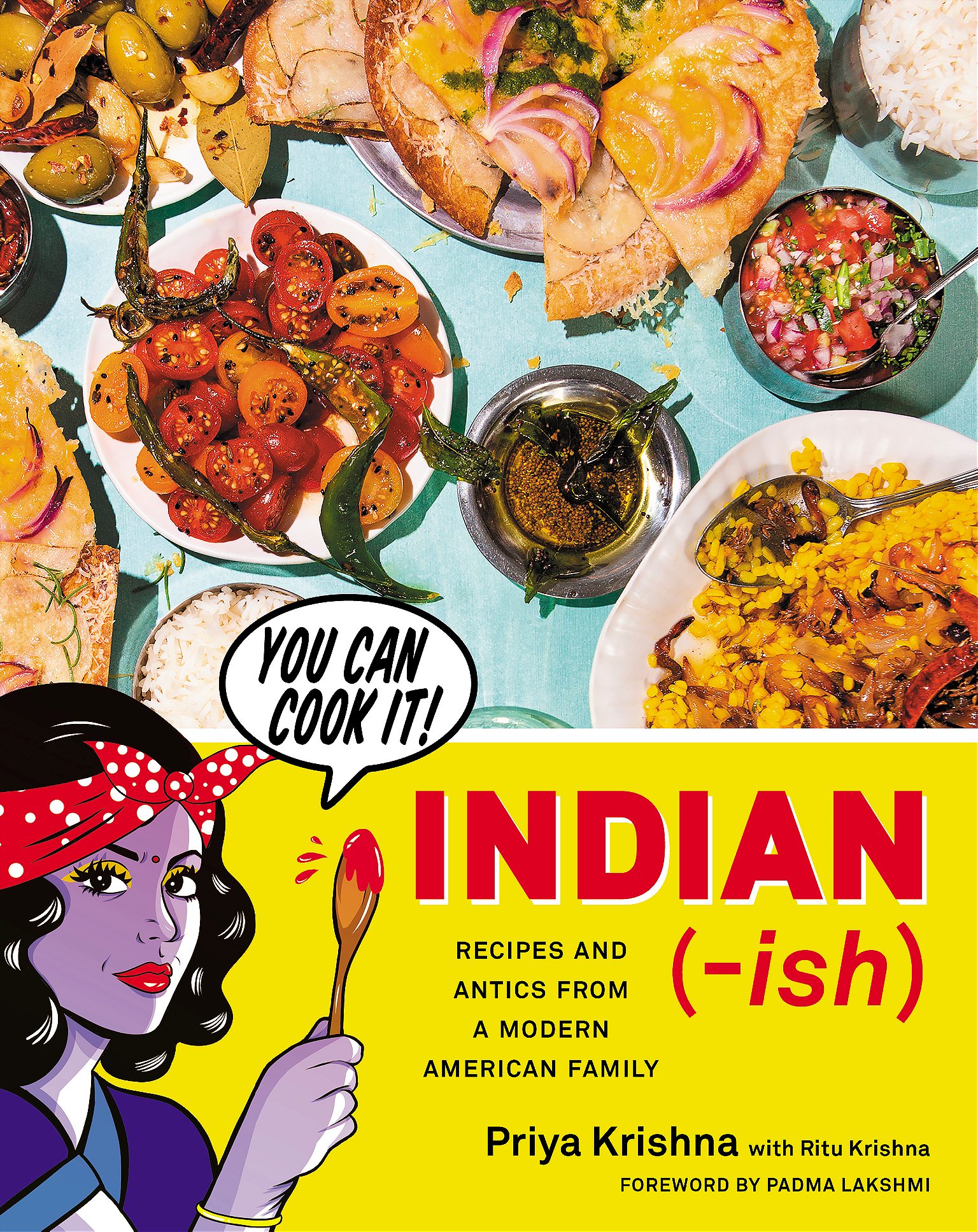

Priya Krishna is bringing her family’s unique recipes to the world with her new cookbook, “Indian-ish.”

Priya Krishna is a food chronicler, a YouTube sensation, and now, a published cookbook author. Her journalism has always highlighted unlikely stories, from an Instant Pot chef to Texas’s cult grocery store. Her new cookbook, Indian-ish: Recipes and Antics from a Modern American Family, is doing the same, but for her own family.

On top of being a software programmer who helped design airport check-in machines, Krishna’s mother, Ritu, is an accomplished home cook who adapted recipes from her home of India using American ingredients. In Indian-ish, Krishna tells the story of her family through their unique food, such as her mother’s atypical substitution of feta for paneer or her father’s insistence on only eating homemade yogurt. Roads & Kingdoms’ Leo Schwartz spoke with Krishna about why her goal is not only to share delicious recipes but to demonstrate why her family is the modern American family.

Leo Schwartz: So I know you got your start at Lucky Peach, a venerated food publication, and you were working in marketing. How did you start food writing?

Priya Krishna: Yeah, marketing, press, and events. This nebulously large role. My very first job for Lucky Peach was actually in customer service. Say you needed to change your address for your subscription, there was a hotline—I was the person on the end of the hotline. Even though my job was menial, I was just so happy to be a part of this club of people doing amazing things in food. I was working out of the Momofuku office, with Dave Chang just walking in and out of the office every day. I felt like I had made it.

Rachel Khong and Chris Ying encouraged me to write later on when we launched our website. Early on, I was really terrified to pitch stories. I was 21 years old, and I just wanted to do a good job. I was too focused on not fucking up at the job that I wasn’t even thinking about pitching stories.

The person who really pushed me to write about food was actually not someone at Lucky Peach. It was Kerry Diamond, who runs Cherry Bombe. I wrote a story for her and one of the early issues of Cherry Bombe, and she told me, “You need to be a food writer. You’re on the wrong side of the masthead.”

As time went by, I realized that while I liked doing events and marketing, it didn’t feel like what I was supposed to be doing. I ultimately love chasing stories. I love falling down deep rabbit holes. I love talking to people.

Schwartz: A lot of your food writing focuses on the anthropology or politics of food, like your oral history of street food for Grub Street. What made you decide to pursue more recipe-focused food writing as well?

Krishna: The through line in all my writing is that I want it to represent a corner of the food world that is not well-represented, whether that’s giving an in-depth oral history of the humble Halal cart or talking about WhatsApp, an app that some people in America haven’t even heard of but is ubiquitous in India. I like giving a voice to people who otherwise wouldn’t be in a publication like the New York Times or Bon Appetit.

When it came to Indian-ish, it was really important for me to present this as my normal. In most food publications, what is considered mainstream is grilled chicken and spaghetti. I wanted to write a book and explicitly call it an American cookbook and have there be dal chawal, have there be dips, have there be pizza made with roti and noodles seasoned with turmeric and mustard seeds, and not present it as exotic or foreign or other, but just as the food that I grew up with. This is the food my mom put on the table when she came home from work and only had 20 minutes to cook.

People think that Indian food is overly complicated or heavy or not good for you, but my experience was the opposite. By presenting that experience, hopefully, that type of food and brown people writing cookbooks will become a bit more normalized.

Schwartz: How did you come up with the idea for Indian-ish?

Krishna: It wasn’t my idea. My mom had contributed recipes to one of the Lucky Peach cookbooks called Power Vegetables. She gets a special acknowledgment in the book because she contributed more recipes than anyone else. Everyone at Lucky Peach knew of my mom—her being this insanely successful software programmer who also was an amazing cook.

When I gave recipes to our recipe developer, Mary-Frances Heck, to test, she came back and told me, “All of these are home runs.” The editor for our cookbooks, a woman named Rica Allannic, had breakfast with me and said she wanted a book of just my mom’s recipes: an accessible entry point into Indian flavors that also tells a modern story about what an American family looks like and what a mother-daughter relationship looks like.

Schwartz: The tagline for Indian-ish is “Recipes and antics from a modern American family.” Fusion is sort of a dirty word, but a lot of the recipes you do for Bon Appetit and for the book are hybrid recipes, like saag paneer with feta and dahi toast with sourdough. What’s your approach to this type of food, that’s not necessarily traditional, but how your family makes it?

Krishna: To me, the connotation of fusion is this unnatural bringing together of ingredients, but it was very much how my mom cooked. She immigrated to this country. She had these flavors that were familiar to her, but she couldn’t find certain things, so she found ways to innovate. She couldn’t find paneer, so she used feta. She had no idea how to make pizza dough, so she made roti pizza.

Some of my favorite restaurants in the country are ones that are born out of immigrants coming to a new country, not finding all the ingredients they’re looking for, and discovering new ingredients—the wonderful marriages that are born out of that. I wanted the book to speak to the beautiful tension that exists between the first generation and the second generation, and how my mom used food as a way to bridge her home culture with this new culture that she found.

I think it’s a really wonderful thing, and I see it happening more and more. It’s not unique to my mom, but I do think that the things that my mom came up with are pretty unique. I said it on the Bon Appetit video: I like saag paneer, but I love saag feta.

Schwartz: Have you gotten any negative reception from family and friends in India for these hybrid recipes?

Krishna: Weirdly, I anticipated there being a ton of pushback, but with the saag feta, surprisingly there hasn’t been. Actually, when I published that recipe, people came out of the woodwork to tell me they made it with mozzarella, or tofu, or seared halloumi, which sounds really amazing. Maybe what I’ve unintentionally tapped into is a shared experience of kids who grew up in America and found these clever ways of adapting their family recipe.

My bhua, which is my dad’s older sister—she’s in her 60s—called me yesterday and told me, “I made your saag feta.” I thought she was going to lambast me, but instead, she said,”And your uncle asked me to make it again tonight! It was so good!” So I’m like, OK, if these 60 and 70-year-olds are receptive to this, maybe I’m on to something.

How did you get started with the Bon Appetit videos?

Krishna: When I was asked to do the videos on Bon Appetit, I hadn’t realized what a phenomenon they were. I’d seen them pop up on my Facebook, but I didn’t realize there were entire accounts devoted to making memes out of Bon Appetit people. So I made one video for dahi toast, and all of a sudden people were randomly emailing and Instagram messaging me.

I realized that I really liked doing videos and that it was a great way to share my recipes in an accessible way. Bon Appetit does a really good job of not trying to sanitize the videos but really showcasing personality. I’m not a trained chef by any means. I worked in restaurants, but I don’t have the expertise that people like Carla do in the kitchen. But I think what’s wonderful about those videos is that they lean into the fact that I’m not a professional. I’m just an average home cook trying to recreate my mom’s recipes.

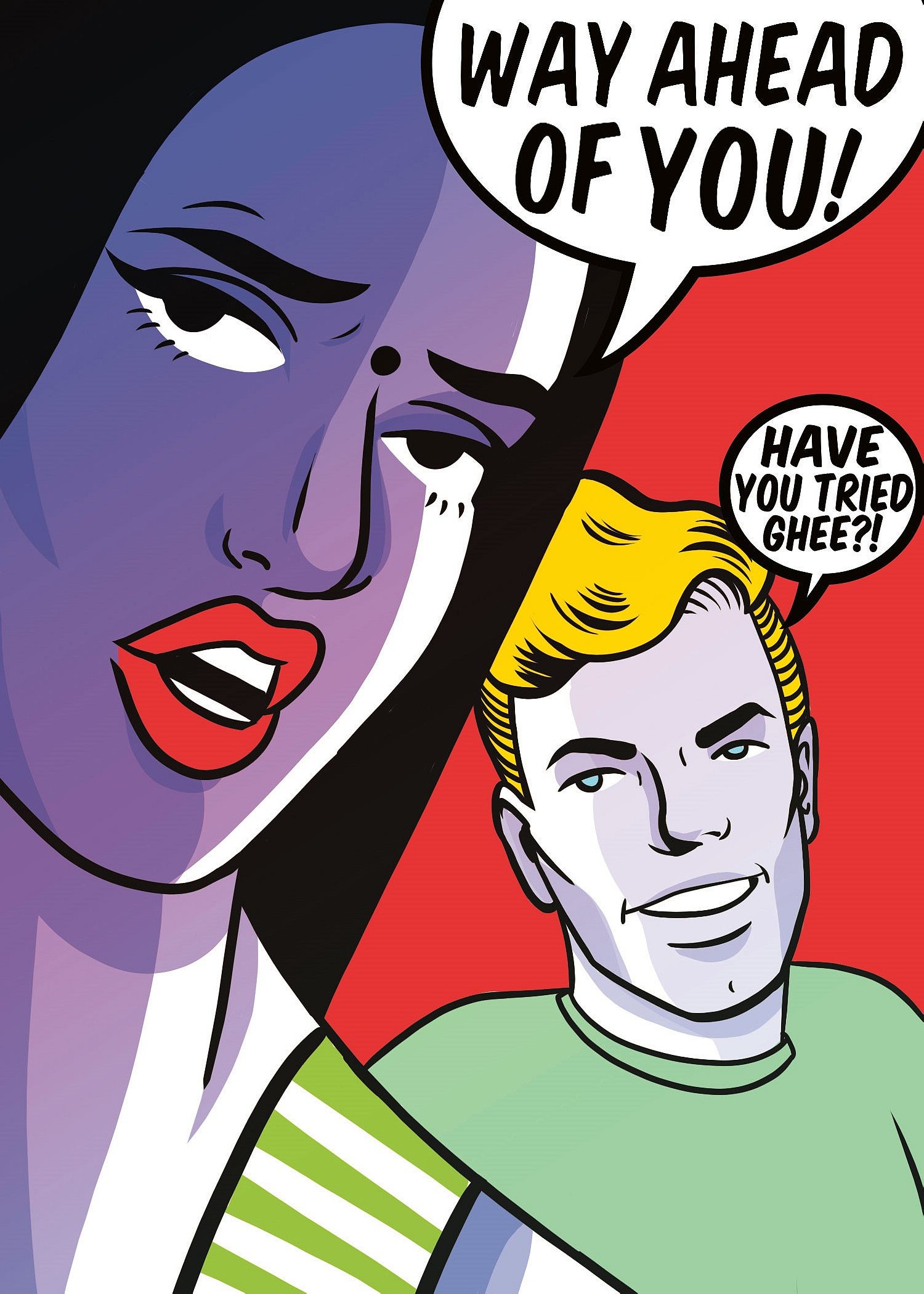

Schwartz: You collaborated with Maria Qamar, who did the illustrations in the cookbook. How did that come about?

Krishna: I am obsessed with her art. I’ve loved it for years and years. I love the way that she is inserting Indian figures into the pop art genre, where Indians have never had a place before. And also that she speaks to these very real aspects of being an Indian, like the overbearing Indian parents, the gossiping aunties, and the way that she intermixes Hindi and English—I feel so seen in those illustrations.

I felt like it could be my family in those illustrations. I wondered, “what if it actually was my family in those illustrations?” When I wrote the proposal for the book and I made a vision board, it was all Maria’s illustrations. And when they asked me who I wanted to do illustrations, I said, “It’s Maria or no one.” We called her, I made my pitch, and thankfully she said yes.

She asked me to make a video of my whole family, so I made a video of our Thanksgiving. I interviewed my mom, I interviewed all my aunts and uncles, I went into my mom’s closet, I showed all the saris. Maria basically made illustrations based off of my family’s unique quirks, but also in ways that would be relatable to other people. There’s one illustration of a white guy saying, “Have you heard of ghee?” which speaks to every Indian being asked if they’ve heard of this Indian ingredient that has existed in our culture for centuries and centuries.

Schwartz: Have you shown your family the final product?

Krishna: My parents saw the book, and then my aunts and uncles also came to my house and saw the book. At first, my parents were confused as to why anyone would buy a book of our very simple family recipes, but now seeing the narrative and the way the photographs and illustrations and the story all came together, they’re really excited. Plus, who gets the opportunity to codify their family recipes? These will exist for years and years to come after I’m gone, and after my mom’s gone. That’s exciting to me.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.