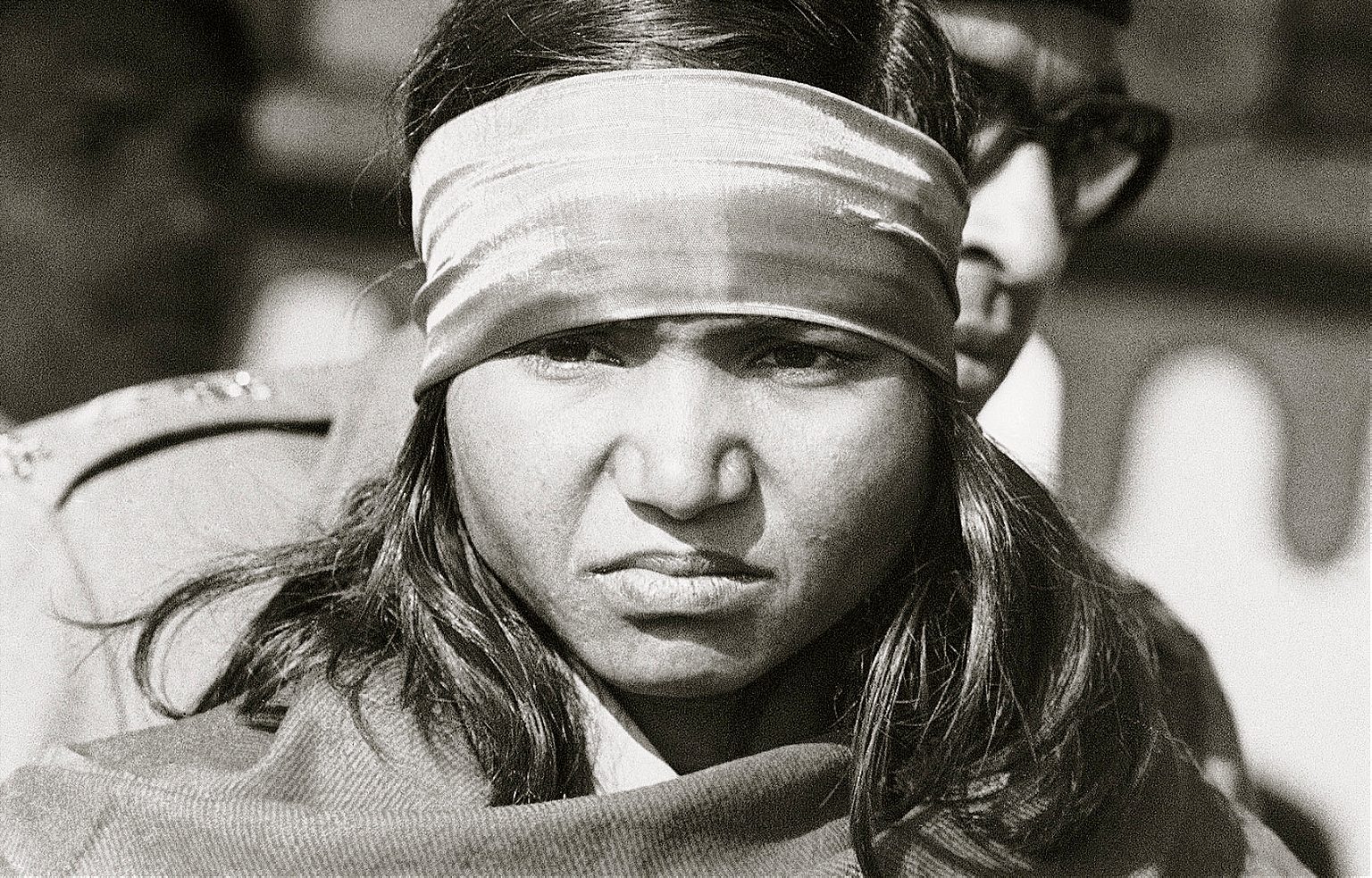

Phoolan Devi’s legacy—as a murderer, goddess, and liberator—masks the woman behind the stories.

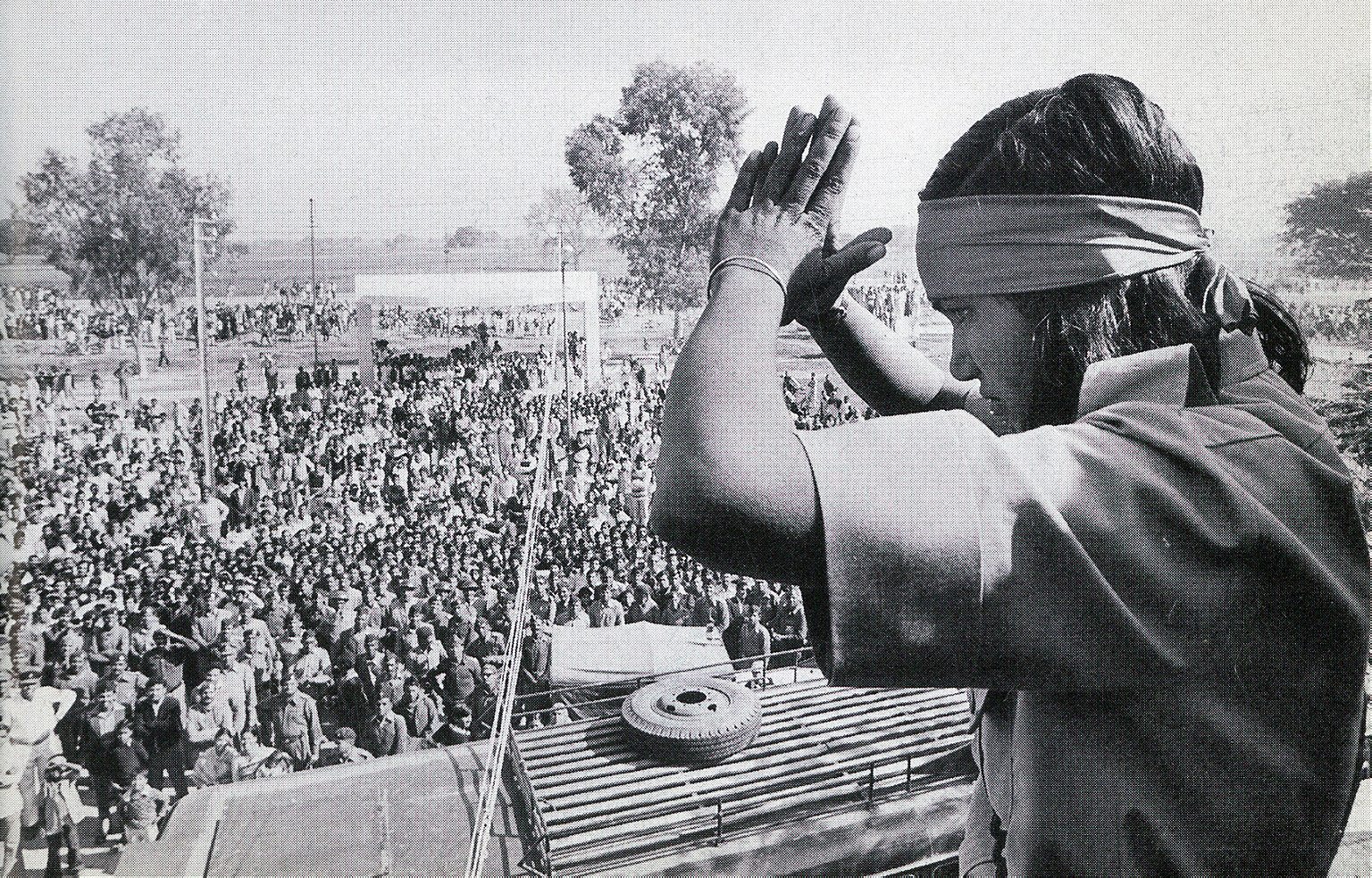

On a chill February day in 1983, a 20-year-old young woman known as Phoolan Devi—literally, Flower Goddess—walked out of the forested ravines of the Chambal River valley and handed over her gun. She bowed to images of Gandhi and the goddess Durga and surrendered herself to the Chief Minister and Chief of Police of Madhya Pradesh state in central India. The cheering crowd of 8,000 people gathered that day—journalists; politicians; some 300 cops; and others from across the dry, impoverished center of the world’s largest democracy—knew Phoolan Devi as a hero, a bandit, a murderess, and a goddess long before they saw her in the flesh. Phoolan Devi, India’s celebrated Bandit Queen, was not a woman, but a legend.

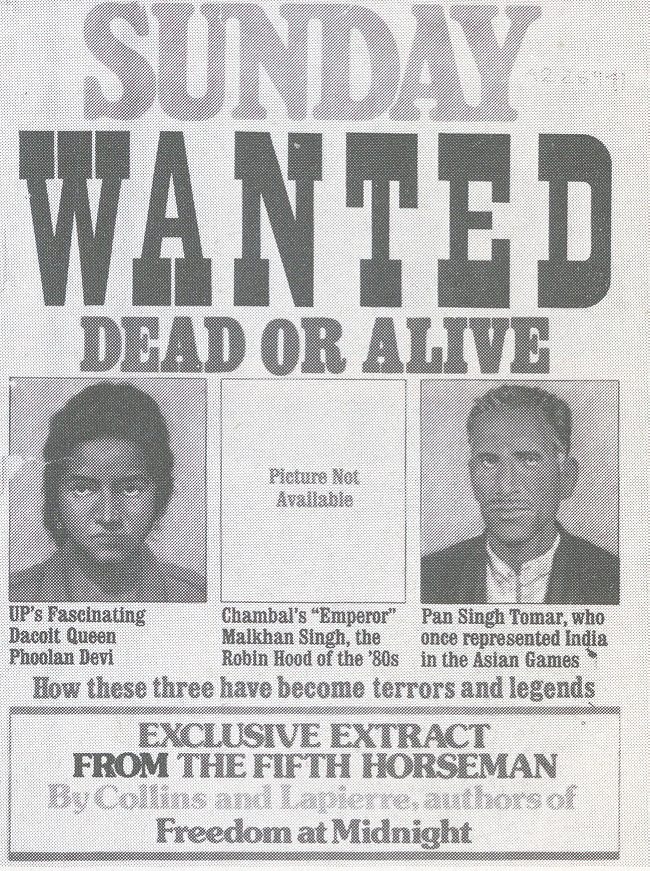

Born to a low-caste household in 1963 in a village on the banks of the sacred Yamuna River in the vast north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, Phoolan Devi was, by the time of her surrender, wanted on 22 counts of murder and another 26 counts of kidnapping and looting. At 31, after a decade in prison, she became the subject of a major Bollywood film, Bandit Queen, which she criticized and which, as Arundhati Roy pointed out in a two-part evisceration called The Great Indian Rape Trick, calcified a problematic version of her life (and its meaning) into accepted fact. Four years after that, she was elected to her first term in India’s parliament, the first low-caste woman to hold that distinction. In 2001, at the age of 37, while serving her second term, she was shot dead in front of her home in Delhi for still-unknown reasons.

Hers is not a life overburdened with hard facts. In making the fictionalized epic Bandit Queen, filmmaker Shekhar Kapur said, “I chose Truth, because Truth is pure.” In reality, the only nonfiction account of Phoolan Devi’s life is the book by Mala Sen on which the film is ostensibly based and which itself contains several divergent, and often contradictory, versions of Phoolan’s life. The Kapur film, rather than capturing the complex realities of Sen’s book, portrays Phoolan Devi as a noble victim. In an interview for Mary Anne Weaver’s excellent 1996 essay for The Atlantic, Phoolan Devi said the film showed her “as a sniveling woman, always in tears, who never took a conscious decision in her life.” She was a symbol of womanhood scorned and avenged, not a human being.

When the Iranian documentary filmmaker Hossein Fazeli first heard about Phoolan Devi five years ago, he was shocked to learn that no documentary had ever been made about her life. “I have a lot of respect for Kapur and I think he’s a very interesting filmmaker, but I think Bandit Queen is a bad film; it gets a lot wrong,” Fazeli told me recently. “At the time it was made, there were a lot of rumors and legends and not a lot of facts.” Not much has changed—if anything, Phoolan Devi’s legend has grown since her death—which is why Fazeli has already spent countless hours interviewing family members and prominent intellectuals across North India, a process he hopes to complete once he’s secured sufficient funding, in part through a Kickstarter campaign.

In conversation with Fazeli, noted Delhi-based journalist Purnima Tripathi says, “We put our goddesses in frames and install them somewhere. If those goddesses were to step out of those frames and speak out, we would stop worshipping them.” Phoolan Devi, after a short life of speaking out loudly, has been securely placed in her frame. “She was a fighter,” Tripathi says, “not a larger-than-life Bandit Queen, not an outstanding politician, but a woman who refused to go down because of adversity in her life.”

The window of opportunity to remember that woman, rather than the legend she became, gets narrower every day.

Bollywood became particularly enamored of the subject of highway bandits

It’s not hard to understand how Phoolan Devi became an icon; her story—as a woman, and especially as a poor, low-caste woman—is sensational and singular, but also tragically paradigmatic.

Phoolan Devi’s first rebellion comes at the age of ten when she confronts an uncle and cousin who, she learns, had stolen her father’s land by falsifying village land records. She publicly taunts and humiliates them; in return, she’s beaten unconscious with a brick. A year later, at the insistence of the same uncle, Phoolan Devi is married off to a 45-year-old widower in a distant village in exchange for a cow and bicycle. A few days later, she comes home. A year after that, she’s returned to her husband, stays a few months, then comes home again. For his 1981 essay “Phoolan Devi, Queen of Dacoits,” Khushwant Singh, another legend of Indian letters, spoke at some length with Phoolan Devi’s family and reports that, when Phoolan Devi comes home the second time “her mother describes her as being ‘filled up’—an Indian expression for a girl whose bosom and behind indicate she has had sex.” He continues, “A girl leaving her husband brought disgrace on the family. ‘I told her to drop dead,’ said her mother. ‘I told her to jump in a well or drown herself in the Jamuna.’” At the age of 12, Phoolan Devi was considered ruined.

She spends her early adolescence in the village grazing the family’s buffalo and takes up with the son of the village headman. She develops a reputation for promiscuity and is sent away to her sister’s home in a nearby village, where she and her distant (and married) cousin, Kailash, start an affair, a dalliance reportedly built on mutual flirtation and seduction. She runs off with him to be married but he returns to his first wife not long afterward. Phoolan Devi goes home. On Jan. 6, 1979, she was arrested for stealing from the home of the same uncle who had repeatedly wronged her, the only arrest in her brief, eventful life (much of Singh’s account of her early life is based on the deposition she dictates to the police at that time). In retribution, the cousin who had beaten her up years before burns her father’s crops. Released from prison two weeks later, she attacks the cousin with a rock.

Fed up, the uncle orchestrates a kidnapping by one of the many bands of armed robbers—known by outsiders as dacoits, or bandits, and amongst themselves as baagees, or rebels—that patrolled the Chambal Valley. In her interview with Fazeli, Phoolan Devi’s younger sister, Choti Devi (Little Goddess), recalls “my sister jumped from the roof to run away, but the bandits caught Shiv, my brother. Then she returned and said, ‘leave my brother, I will come with you.’”

Dacoity had been a major part of central Indian life for centuries. The word thug in English is, in fact, a Hindi word referring to a specific community of highway bandits that patrolled Central India for at least 500 years before the British East India Company created a “Thugee and Dacoity Department” to see to their eradication. The deep ravines and dense forests of the Chambal Valley had been fertile ground for dacoity for as long as anyone can remember. In the 60s and 70s, the last great flourishing of dacoity in Central India before its near eradication in the 1980s, Bollywood became particularly enamored of the subject.

However, the romance of dacoity presented to city audiences bears little resemblance to Phoolan Devi’s experiences as a low-caste woman in a mixed-caste gang with high-caste leadership. Phoolan suffered repeated rape by gang leader Babu Gujjar, and, most likely, by the rest of the gang, as well. One night, gang member Bikram Singh, part of the same low Mallah (or fishermen) caste as Phoolan, shoots Babu Gujjar in the head, becomes the head of the gang, takes Phoolan as his lover, and, at Phoolan’s command, forbids anyone else from touching her. This doesn’t sit well with some of his fellow gang members, particularly a pair of brothers from the high Thakur caste called Lal Ram Singh and Shri Ram Singh. Bikram Singh is, by all accounts, Phoolan Devi’s great love.

What happens next forms the crux of the Phoolan Devi legend. On Aug. 13, 1980, Lal Ram and Shri Ram Singh murder Bikram, kidnap Phoolan Devi, and lock her away in a Thakur village called Behmai where they—and, presumably, many others—repeatedly gang rape and publicly humiliate her over the course of three weeks. She is, at this point, 17 years old. One night she manages to escape, joins a new gang, and convinces its leader to help her take revenge. On Feb. 14, 1981, she leads the gang into Behmai (or so the commonly accepted story goes; Phoolan herself contests this version of events) and demands that the villagers turn over the brothers. They claim never to have seen them. She has 30 men marched to an embankment and, when they still don’t cooperate, orders her men to shoot. Twenty-two of them die. She becomes the most wanted person in India, with a $10,000 price on her head. To this day, Fazeli says, villagers in Behmai are skeptical of anyone entering town with a camera, certain that he or she will be sympathetic to Phoolan Devi whom they still view (understandably) as a cold-blooded murderer.

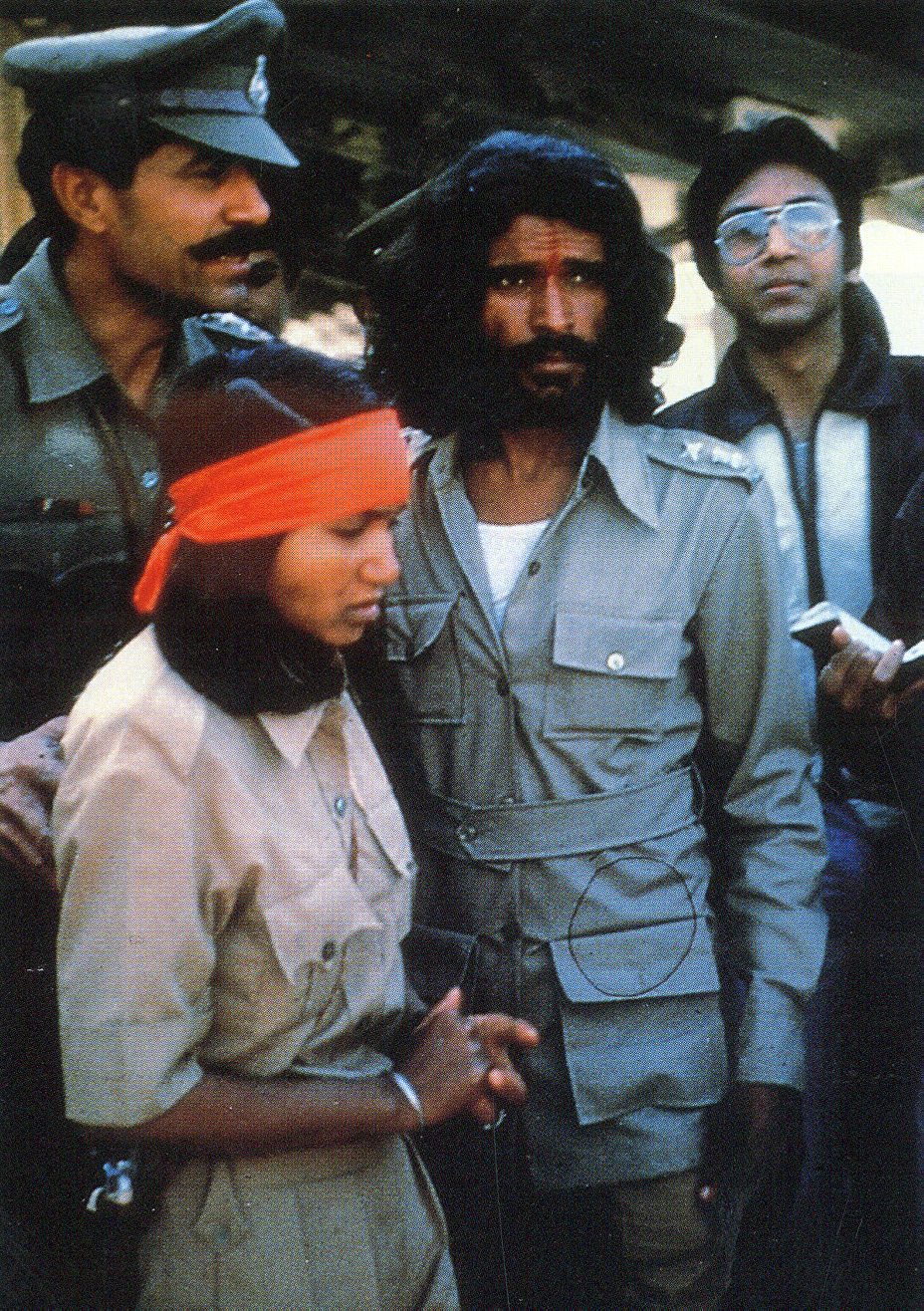

Two years later, she surrenders to the police under carefully drawn conditions. She demands that her gang members get no more than eight-year sentences, that her family members who have been jailed because of her be released, and that her own cases be tried only in special courts in Madhya Pradesh to protect her from retribution from angry Thakurs, the caste that, in effect, ran Uttar Pradesh. She spends the next 11 years in jail.

By the time she dies in a pool of her own blood on a leafy street in New Delhi 18 years later, the legend of Phoolan Devi, the avenging goddess, has already taken form.

In December of 2012, more than 30 years after Phoolan Devi reportedly took her revenge on Behmai, a young woman is brutally gang-raped by a group of men on a bus in Delhi. She later dies of her injuries. India responds with outrage. Her identity is protected by law, so papers and people alike start referring to her as Nirbhaya—Fearless—sometimes translated as The Brave One. New laws are passed requiring that court cases connected to rape charges be expedited through India’s notoriously inefficient judicial system and that those found guilty be punished with the death penalty. (Marital rape is, even today, not considered rape unless the wife in question is under 18 years old.) A nameless, faceless woman becomes a symbol for the suffering of women across the Subcontinent. She is fearless, though given the horrific circumstances of her death, this seems not just unlikely, but also, perhaps, inhuman. “When a woman becomes womanhood,” Roy wrote in her essay on Bandit Queen, “she ceases to be real.” Nirbhaya, too, becomes a symbol.

The rage that roiled (and continues to roil) India following Nirbhaya’s death may never have been possible without Phoolan Devi. It might have been equally impossible had Nirbhaya survived her assault and emerged as a real, complex human character, a young woman with a job, returning home late, out with a boy who was not her husband: some of the many excuses made by India’s politicians to excuse the countless sexual assaults that take place daily. Nirbhaya and Phoolan Devi are heroes in part because they are not quite real. They’re screens onto which we project our fantasies of bravery, salvation, and justice.

Phoolan Devi offers a rags-to-riches story more profound and satisfying than anything Bollywood could dream up

For the poor and dispossessed, Phoolan Devi offers a rags-to-riches story more profound and satisfying than anything Bollywood could dream up. She is a symbol of womanhood abused and transcendent. As the late Kalyan Mukherjee, the first journalist to write about Phoolan Devi, puts it in his conversations with Fazeli, “she represents the paradigm that a dispossessed woman can make her own path in this country.”

That’s an appealing story. It is also generally a false one. Dr. Ranajana Kumari, Director of the Centre for Social Research in Delhi, says that more than 40 percent of marriages in the states of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh (where Phoolan grew up) and Madhya Pradesh (where she lived as a dacoit) are of girls 18 and under.

“Women are the poorest of the poor,” she says in an interview with Fazeli, “They eat the last and the least. They wake up first and go to sleep last. They work 18-20 hours a day while suffering malnutrition.” Domestic violence remains the norm in India, including marital rape. This is the life that Phoolan Devi narrowly escaped. She was an extraordinary woman, and, literally, an exceptional one.

Rape is still, often as not, blamed on the victim, and still makes that woman ineligible, or at least undesirable, for marriage and childbirth, says Purnima Tripathi. “Our attitude is such that 90 percent of women who are raped have asked for it, and the judicial process in India is so humiliating it’s like being raped again and again,” Tripathi says. “This is what makes Phoolan different: having gone through all that she still had the courage to come out and start again.”

Depending on who you read and when they were writing, you may or may not read about Phoolan Devi’s various lovers who were also her partners in crime. Her own agency in her sexual life is an important part of who she was as a woman, but it is incompatible with some of the myth-making that surrounds her. Roy points out that this is why Kapur’s film focuses on Phoolan Devi’s sexual humiliations, says nothing of her sexual conquests, and allows her just one lover, Bikram Singh, who also happens to be her savior. “The Rape of a nice Woman (saucy, headstrong, foul-mouthed, perhaps, but basically moral, sexually moral) is one thing,” Roy writes. “The rape of a nasty/perceived-to-be-immoral woman, is quite another.” It’s why, at the end of Khushwanth Singh’s essay, he quotes a police superintendent in the region where Phoolan Devi was, at the time, still operating as saying, “‘I don’t look upon her as a dacoit but as a child that has lost her way. We will find her and put her on the right path.’”

Did Phoolan Devi change the moral calculus of womanhood in India? Perhaps not. “Today if a girl talks back to her parents, they might say, ‘don’t talk back, don’t be a Phoolan Devi,’” Mukherjee tells Fazeli in their interview. “In India,” Tripathi says, “femininity means total and complete submission.” But that should not undermine the power of Phoolan’s actions or the inspiration that, even in their sanitized form, they can provide.

That first fight for her father’s land was not about gender or caste, but about class, about claiming her rights, and her family’s right to justice under the law. For low-caste people, her ability to rise to a position of political power, to hold elected office despite the fact that she never learned to read or write, was a dramatic disruption of the structures of political power. It cleared the way for other politicians, most notably the exceedingly colorful (and exceedingly corrupt) Mayawati, a Dalit (the lowest community in the hierarchy of Brahmanical Hinduism) who became chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, the same state where Phoolan Devi served.

As early as 1994, when Phoolan Devi was still alive, Roy wrote, “Phoolan Devi the woman has ceased to be important […] she is suffering from a case of Legenditis. She’s only a version of herself.” Fazeli hopes that his film can, at least to some extent, serve as a corrective. “I think, in a sense, that society is remembering Phoolan in a safe way. I felt I had to demystify her. Everyone was talking about her as a hero or a goddess and I wanted to talk about the person,” Fazeli says. “She’s not a pasteurized character.”

Fazeli is also interested in the universal import of Phoolan Devi’s experience at this particular cultural moment, as many societies finally wake up to the fact that sexual assault is happening everywhere, all the time. The struggle now is to keep young women from internalizing violence as ordinary. For the rest of society, the message is clear: we don’t need the “nice” version of Phoolan Devi to condemn what was done to her. It’s not just goddesses who have a right to fight back.