A conversation about Japanese tattoo culture, Sailor Jerry, and being at peace with Stupid White Guy Tattoos

I first met Kotaku editor Brian Ashcraft at a high-floor Osaka cafe overlooking the whirring jumble of Umeda Station. In that single vista out the window there could have been a hundred things I didn’t understand, from the neon storefront kanji to the intricate patterns of pedestrians. It’s something you get used to in Japan: knowing that you know nothing. That is also what makes Ashcraft such an invaluable journalist. He is an American with 15 years in Japan, and a deep patience for researching and then explaining his adopted country to outsiders. His new book, Japanese Tattoos: History * Culture * Design is a continuation of that work, an accessible yet deep taxonomy of the ancient art and the people who practice it. I caught up with him by Skype recently to talk Koopa Troopas, Sailor Jerry, and whether or not the kanji on my shoulder qualifies as a stupid white guy tattoo.

Nathan Thornburgh: Tell me about your job at Kotaku [Gawker’s gaming blog, now owned by Univision]. I think that’s what brought you to doing

a book on Japanese tattooing.

Brian Ashcraft: Right, so I’m the senior contributing editor there. I’ve been with Kotaku since 2005, which in internet time is maybe about 1000 years. It’s been great, I handle a lot of the Japan-centric content because that’s where I’ve lived since 2001. I’m fortunate to work for a site like Kotaku. It’s a site that if I didn’t write for it I would read it.

Nathan: And after Gawker.com shut down Kotaku is still going strong?

Brian: Yeah, as you know, Univision purchased us and everything seems to be kind of continuing as normal. I think everyone seems pleased with Univision. We’ve been trying to do the best work that we can, so we’ll just keep doing that.

Nathan: Not worrying too much about the headlines, just putting your head down.

Brian: It’s like anything, everybody does the best work they can and they hope people will look at that. I think that for Kotaku, at least, that’s always been the attitude.

THIS COUNTRY MAKES ALL THE STUFF YOU LIKE

Nathan: Did the cosmos of interests that defines Kotaku drive you to Japan? Or did you realize when you got there that there was this entire world of gaming and nerdiness and kind of awesomeness in Japan?

Brian: I’ll give you the CliffsNotes version. As a kid, I was always interested in Japanese culture. There was a foreign exchange student from Japan who came to my grade school and I went over to his house once and it blew my mind that he had Famicom, the Japanese version of the NES, and it looked different from my console, and the games were all in Japanese, so that blew my mind as well, the cartridges were shaped differently but it was still Nintendo and it still had Mario on in, so that kind of thing, as a young kid, growing up in the 80s I think a lot of kids probably felt this way, that Japan seemed like a very interesting place. There was a kind of an instant fascination: “This country makes all the stuff you like.”

Nathan: And where was this you were growing up?

Brian: I grew up in Texas, in Dallas. But during the late 90s, I was interning at Quentin Tarantino’s distribution company, Rolling Thunder Pictures, and my boss Jerry Martinez was trying to buy the rights to some Yakuza movies and some monster movies and he went to Japan and he came back and he said, “It’s the greatest place I’ve ever been to.” So I thought when I graduate from college, I should go to Japan and see what it’s like. That turned into 15 years.

Nathan: That is how life happens.

Brian: Right, right, right. I was here for a few years and I started getting kind of small writing jobs from Wired, and then I became a contributing editor there. When I was in junior high school I had dreams of becoming a writer. I thought, “You can stay home all day, and they’ll pay you money to stay home and write stuff.” And that became possible. Then [Wired contributing editor] Brendan Koerner said there was this company called Gawker Media looking for writers for their video game site. I liked video games and Japanese geek culture, so I was interviewed via phone by Lockhart Steele. And that turned into Gawker.

Nathan: So basically you found the opportunity to fulfill middle school dreams.

Brian: Pretty much. it was like, “What I can do to enable me to stay home all day?” I’m sure you feel the same way, I get an immense amount of pleasure from writing. I enjoy the act of writing very, very much.

Nathan: You are a masochist.

Brian: I like it. I think it’s a lot of fun.

Nathan: So you are essentially living this dual existence, right? You’re an American but you’ve obviously been in Japan forever, you have a Japanese family, your kids are going to school in Japan. It seems like a lot of your professional life is explaining Japan back to Americans. Does that get more difficult the deeper you get?

Brian: The best way to explain it is kind of like video game design. The way they introduce different enemies in Super Mario World 1.1: one Goomba comes at you, then you get a Koopa, or a Koopa Troopa will come at you and it’s done in this very logical fashion. Same with explaining Japan. If you give people the proper context I think you can explain anything. The other thing that really helps, is if you realize it’s a different culture, but it’s not like people are walking around with hamburgers on their feet and eating shoes, people have the same boring kind of conversations they have everywhere else.

Nathan: But you’ve got to work your way up to the culture.

Brian: I think so. This year, I feel like I know more about Japan than I did last year, and last year, I knew more than the previous year, so every year it becomes this experience that just grows and grows and grows. When I go and read Japan writers who lived here, somebody like Donald Ritchie who lived here for forever, there’s this wealth of experience. It’s just putting in the time and showing up and being there, a lot of it’s that.

Nathan: Was this your first deep dive into a subsection of Japanese culture?

Brian: No, the first book I did was about arcades. As I started it, you start making these connections about urban planning. Like “wait a minute. Arcades are often near train stations.” You start noticing bigger picture things, so even if you’re just writing about arcades, you’re talking about larger cultural trends.

For tattoos, the thing for me was always, “Why does this society not respect people who get tattoos or tattoo artists, and what does it all mean?” It ended up being the most exhausting, intensive, research I’ve ever done for anything. It ends up being this really, really broad subject matter and one of the first interviews I did, we talked to Horiyoshi III and he’s like, the most famous tattooer in Japan, and something he said that really kind of resonated was “You’ll find, in a funny way, that tattooing is connected to everything.” And he was right.

Nathan: That is also sort of like Mario Brothers World 1.1, right? In Japan, once you figure out the vending machines, then you can move on to platform etiquettes. It always felt like this discrete series of tasks that you kind of have to complete before you can move on to the next level. Spoken as someone who is still stuck trying to get level 1.

Brian: I think that’s an accurate comparison. When you first come here, you’ll get kind of praised for very basic things, like “Oh, you can greet people!” or “You’re able to use chopsticks.” The bar is often very, very low. But after you’re here for a while, the bar gets kind of raised higher and higher. So, like, last year, I was on the, what would you say, what’s the group of people that are in a building association for your apartment?

Nathan: A condo association?

Brian: Yeah, a residence association or whatever. So I ended up being the president of that. And it was something was incredibly stressful and it’s something that even Japanese people don’t want to do: looking at cutting costs by switching to LED lights or different internet providers.

Nathan: Homeowners association is literally the castle level. That’s insane.

Brian: Yeah, nobody wanted to be the next president of the association and I just remember sitting in the meeting with like 30 people saying, “look, somebody here has to do it.”

A LOT OF GANGSTERS DO HAVE TATTOOS, BUT NOT EVERYBODY WHO HAS TATTOOS IS A GANGSTER

Nathan: So explain to me a little bit about tattooing and its relationship with polite society.

Brian: One thing to always keep in mind is tattooing in Japan has been traditionally very working class, so it’s kind of like folk art for people who are doing physical, manual labor. Samurai generally did not did get tattoos, and probably one of the big reasons was, you get your body from your parents, and then if you mark on it permanently, you’re defacing it, and if you deface it, you’re being rude or disrespectful to your parents. I don’t think that people now if they look at tattoos, they think, oh this is Confucian thought. But I have Japanese people tell me that, you get your body from your parents, and if you do that it’s rude to your parents, to mark it up that way.

Nathan: The Jews think something like that: you get your body from God, so don’t mark it up.

Brian: Right, similar in a way. And also, people look at Japan and think of it as largely middle class, and it is, but there’s been a hierarchy throughout Japanese history. They got rid of feudalism and these different classes, but it kind of lingers. When people see others with tattoos, they might think “Oh, that’s low class.” For example, in Osaka, if I go to more working-class areas of the city, I know I’m going to see more tattoos on people than where I live, which is in far north Osaka, where there are large houses and people driving German sports cars.

Nathan: It’s just full of homeowners associations run by Texans.

Brian: Right, yeah, pretty much (laughing). That does not mean that there aren’t people here with tattoos. That means that if they have them, they’re doing a very good job of keeping them covered up. But yes, a lot of gangsters do have tattoos, but not everybody who has tattoos is a gangster kind of thing.

Nathan: And Japanese people get that?

Brian: No, I don’t think they do. It’s like when you watch TV, if you see a guy jump out, you’re like, that’s a ninja, if you see a guy jump out with two sleeves and his back all done, that’s a gangster. It’s become part of the pop culture iconography. By the same token, there are magazines that cover organized crime in japan. If you flip through the back of them, there’s going to be a lot of tattooers, advertising their services. But for example, my co-author, who’s also an American, his professional name is Hori Benny. Hori is like doctor, or professor, basically, that’s kind of his title as a tattooer. His clients are all young, hip kids into fashion and music and stuff. These bohemian kids. And he’s doing these geek inspired, he does a lot of more traditionalist work as well, but he does a lot of geek inspired tattoos. He invented the word “Otattoo” which is kind of a mix of Otaku, geek, and tattoo.

Nathan: There’s a nice moment in the book explaining the transition to storefront tattoo parlors from backroom parlors. It’s like a chicken or egg type thing: was it mainstreamed because of the storefronts, or did the storefronts come because it became mainstream?

Brian: Right, and then you have these authorities in Osaka that are trying to clamp down on that now, and saying that tattooing is actually illegal. It’s like they want to drive it back underground. People can kind of say what they want about organized crime, and I think we can all agree that crime is bad, but after the government in like 1870s said “okay, tattooing is illegal,” it was the gangsters, especially during the 20th century, that kept tattooers working, and because tattooers were working, the Japanese tattoo tradition didn’t vanish. If you respect and admire Japanese tattooing as an art form, you have to, in a way, be grateful to them.

Nathan: The gangsters as preservers of the culture, keepers of the flame.

Brian: If you look at, for example, Kabuki, it was traditionally this working class, showy type of theater. But it’s now become this kind of revered and respected, Japanese culture with a capital C. It’s respected now but tattooing has not been brought along with it.

Nathan: So what is going on with Osaka?

Brian: Basically the authorities’ rationale is that if you’re going to pierce someone’s skin and insert pigment, then you need to be a licensed medical practitioner. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to get tattoos from a doctor.

Nathan: Especially as a Texan, it’s got to remind you of HB2 and what they’re doing to try to medicalize abortion, and it’s all kind of a smoke screen. I’m not asking you to comment on abortion, but it’s strikingly similar in some ways, of just kind of using “medical safety” to eliminate things you find disturbing.

Brian: Surely there is an easier answer; this is not it. If people want to go get a tattoo, they should certainly be allowed to do that. Tattooers in Japan take [hygiene] very seriously, but it would be kind of nice if the government helped and supported them. Also, apprenticeship in Japan… people spend years and years and years getting to the point where they can debut as a tattooer, so it’s not like, “Okay, you can’t tattoo anymore…Go do something else.” This is their identity, they see themselves as artisans and as part of this long tradition. You’re forcing people to question their identity, I think instead of looking at it holistically. I think it’s a mistake personally.

Nathan: So what’s happening right now in terms of the livelihoods in Osaka?

Brian: People are continuing. If this court case has an unfavorable outcome for tattooers, they’re not going to stop. It’s like the government often seems to want to promote “cool Japan,” and I think we can all agree that tattoos are pretty cool and foreigners are interested in them, but it’s like, “Cool Japan except for this. We don’t like this.” You have part of the government aggressively promoting tourism, and a lot of foreigners have tattoos, and they’re trying to figure out ways to appeal to these foreigners, and ensure that they can go to hot springs and not be banned because they have tattoos, and so they’ve come up with like, “Okay, how about passing out stickers, and people can put stickers over their tattoos.” And that’s great if you have like a heart on your bicep, but if your whole arm is done, are you supposed to put like 40 stickers on your arm?

A JAPANESE TATTOO IS LIKE A TAILORED SUIT

Nathan: Among the many things I’ve learned about tattoos from your book, are some throwback things you wouldn’t see in Western tattoo parlors, like people bringing their own towels. Tattooing is a very different art in Japan, traditionally than something in the States that kind of got clinical and mechanized earlier.

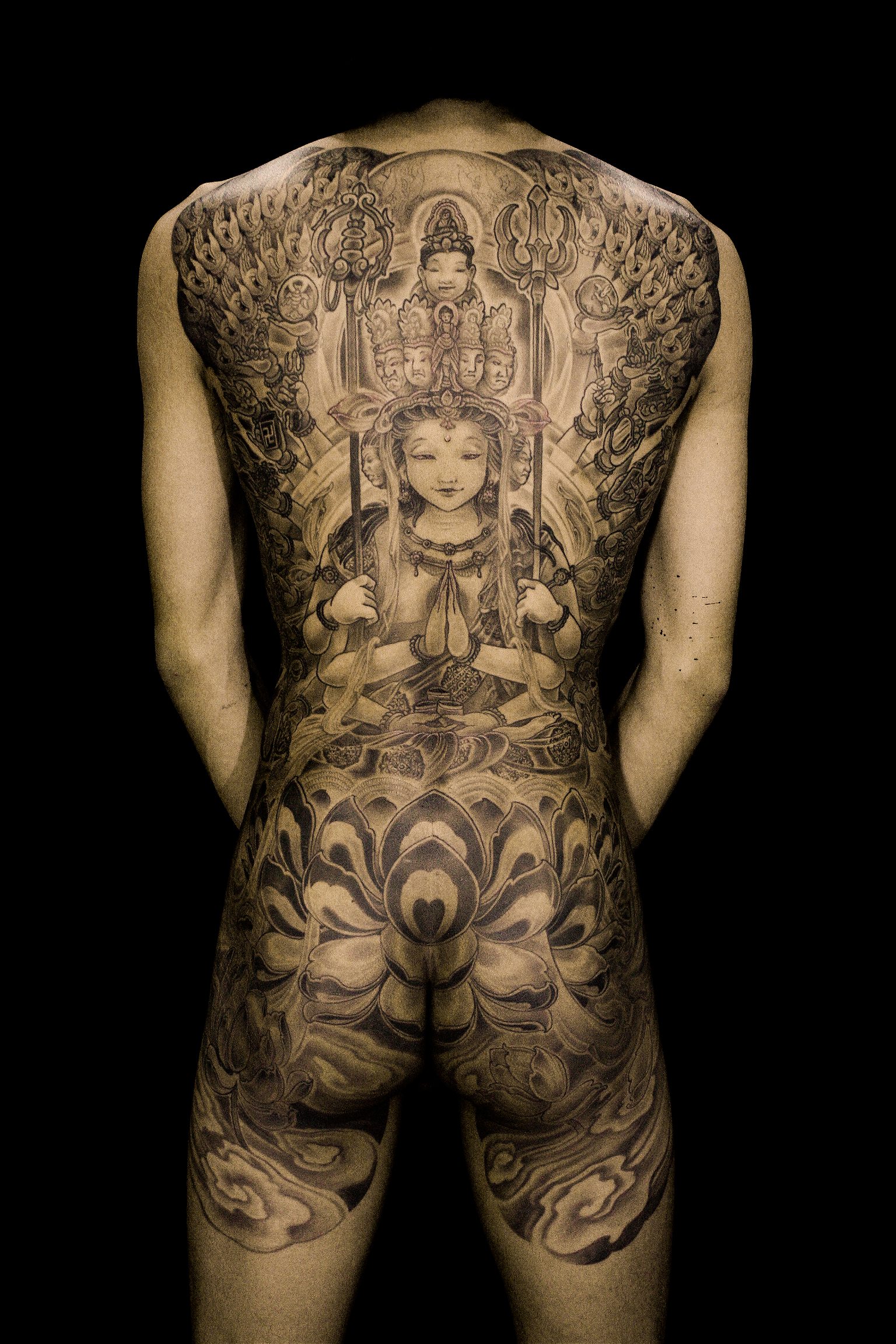

Brian: Yes and no. For example, there’s a picture on the last page where you can see my co-author’s studio. It’s got a nice table, and it’s wrapped in plastic for each customer. He’s taking obsessive care with sterilization, so I think that in the last few decades, Japanese tattooers have gotten a lot more aware. Same thing for American and European tattooers as well. If you listen to stories of like Sailor Jerry was tattooing guys during World War II, and they were just using a sponge and a bucket for everyone. I think the big difference between Japanese tattooing and Western tattooing is going to be the general approach. In Japan, you have central motifs and then you have the background, but it’s also incredibly important, the way it interacts and corresponds to the main, central motif. It underscores so much of the tattoo’s meaning. Whereas traditionally in the West, the great thing about Western tattooing is that people generally get a bunch of individual, one-off pieces. During your life, you can point to different tattoos and say what they meant to you in that stage of your life, whereas if you’re going to get a really large, Japanese piece, you’re thinking of the totality of that piece. It’s like a tailored suit.

Nathan: And that piece can take years or decades to finish?

Brian: It can take a while. It depends on how extensive the work is. It can cost as much as much as a car. Sometimes for gangsters, that has been like a show of wealth. To show, “hey look, look what I have. And this is the artist that did it.” But originally, those tattoos were forms of expression, but also kind of ways to protect their bodies. If they were an early Japanese fireman, they might get their body done in dragons because dragons are connected to water, and they don’t want to get burned.

Nathan: Who is this book for? I think there’s definitely some service to it, things to know before you get a tattoo.

Brian: We felt that there would be two types of readers. People who know nothing about tattoos but are interested in Japanese culture and people who already know about Japanese tattoos and maybe has work done or wants to get work done.

Nathan: So, has your interest in getting a tattoo changed since you started the project?

Brian: It’s probably been the same. For me personally, I have three children, and I’m acutely aware of the fact that if I had any large tattoos or any tattoos at all, it would make my life incredibly more complex. There’d be things I couldn’t do or things that would become very difficult to do with my kids, like taking them to swim school, and after swim school, changing into regular clothes. One of the guys I spoke with in the book, when he was in his 30s and his kids were young, he was like, “I didn’t have any tattoos at all because I couldn’t do stuff with my kids,” and now that they’re grown up, he’s been able to get tattoos that he’s wanted. It really made me respect people in this country who have tattoos or do tattoos. Because it’s not like in the US where it’s like, “I’m going to go get a tattoo,” then your life continues as is. It’s a lifestyle change.

Nathan: So every tattoo is like a neck tattoo.

Brian: It becomes a big change to your life. I have so much respect for the people who have decided to do that and the people who work in the industry. I also felt like going into…I didn’t have any tattoos before, if I suddenly start getting tattoos because of the book, to show street cred or whatever, if I got one tattoo on my arm or just a small amount of tattooing, I feel like that would be insulting to people who’ve spent ten years getting their whole bodies done. I felt like I wanted to cover it in the most respectful way possible. The other thing I found is that tattooers, all they care about is, “Do you know what you’re talking about and are you coming into this with an open mind?” Can I explain to you what it’s like to get your armpit tattooed? No, I can not. But that was the great thing about doing the book with a tattooer. He’s more than willing to add that element.

Nathan: So it’s less about asking what tribe are you?

Brian: I found Japanese tattooers to be among the most open-minded people I’ve met in Japan. Incredibly comfortable with foreigners.

Nathan: Which is rare?

Brian: Right. Sometimes when you meet Japanese people for the first time, depending on their experiences with foreigners, they might not be used to it, so things can get awkward. But there was none of that with tattooers. A lot of them travel abroad and they deal with foreigners as clients and as colleagues, so what they seem to care about is, “Do you understand Japanese tattooing?” Because there’s been lots of books written lots of books written about Japanese tattoos written by people with a lot of tattoos, but that doesn’t mean they’ve written a good book.

Nathan: What would you tell your kids about tattooing when they get old enough to make that decision themselves? Have you talked about that to your wife?

Brian: I don’t think either of us would tell them what to do. My co-author has been to my house and my kids have seen the dragons on both of his arms. I’ve told them to judge people not by how they look, but by the type of person they are. In the years after the war, the 40s, 50s, and 60s, you might go to your local bathhouse to take a bath, because you didn’t have a bath in your home, and you’d see all sorts of people in the bath. Those opportunities have diminished on a regular basis, I think that that might have exacerbated people’s reactions to tattoos.

Nathan: I think you and I met in winter time, I didn’t have a chance to show you my Japanese tattoo, so I’ll give you a slight description and you can tell me, on the atrocious gaijin tattoo scale, what you think… I have the two kanjiof my wife’s last name in that slightly older script, she’s Japanese and her name is Japanese. It basically has a hanko [signature stamp] on it, but it’s not a signature, it says genki, which is a complete inversion of the form. How terrible is all that?

Brian: I think that with tattoos, whatever you get, it should have meaning to you. I think that, as long as you’re happy with it, great!

Nathan: You’re the unitarian universalist of tattooing.

Brian: It’s your body, as long as you’re happy.

Nathan: I got that sense through the book, which was rigorously non-judgemental and kind of informative with an eye not towards weaponizing information. It’s unusual. When I think about people who get really intensely into Japanese culture, it often does get a little weaponized like, “I know this thing that you don’t know.”

Brian: The reason I wanted to work with Benny on this book is that when I met him, we really connected immediately. It was like, “This guy views Japan the same way I view it.” And it was like, you live here and you learn about it, and that isn’t information that can be lorded over others but then can be used to explain stuff. For better understanding. Because you should never forget that you once came here and didn’t know very much, and then even, it’s like I said earlier, there are people who have been here longer, and then Japanese people as well who can go even deeper. Every book that I write, I always hope it will give me another angle on Japan, and that the angle will lead off into the next book, and then maybe by the time I’m 70, I’ll have a good handle on the place.