Longing to Return to a Place You’ve Never Been

Longing to Return to a Place You’ve Never Been

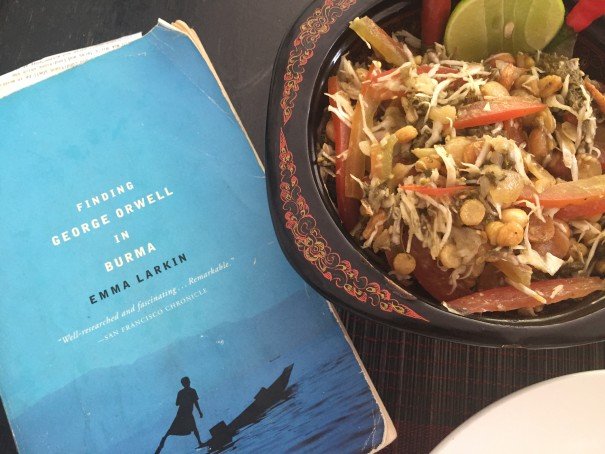

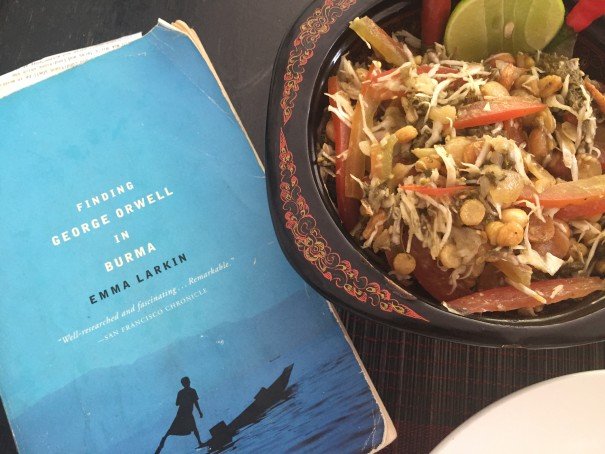

Lahpet in Phnom Penh

The faint aroma of stewing curry leads the way, reassurance that I’m not lost. As soon as I walk into Irrawaddi Myanmar Gallery Restaurant—Phnom Penh’s only Burmese eatery—I meet the owner’s eyes. She greets me with a smile, one that indicates she recognizes me, reinforced when she leads me to “my” table. It’s my third time here this week—today at breakfast time rather than dinner, though my order won’t change.

After weeks traveling alone with little intimate human contact, her graciousness fills a void as if I was enveloped by her soft embrace. Ceremoniously, she asks for my order and we both smirk slightly, ready to play the game.

“Lahpet, khayan thee hnut, and lapea yea with…”

“…no sugar!” she interrupts, as we giggle.

Moments later, a warm vegetable broth is in front of me, drops of oil and slices of soft onion floating about. Somehow—despite my permanent sweat marks from the enduring, sticky heat—this is soothing and not repellent. Mostly, the soup is a distraction from my anticipation for what brought me here in the first place: tea.

I first tried Burmese food in 2014, during a research trip to the Thai border district Mae Sot, a 10-minute drive east from the nearest Burmese trade town. When I wasn’t drinking tea, I was eating tea; the latter a custom of few countries in the world. (This was a treat for me as a tea-lover who is often ostracized for not drinking coffee.)

At the main market, I bought packets of sugary, clay-orange tea mix and strolled on the adjacent sidewalk. From there I could see Burma—renamed Myanmar in 1989 by the military junta—beyond a messy no-man’s-land; a jumble of trees and trash surrounding empty, dusty pathways, occasionally occupied by humans or mangy dogs. Robed monks walked past me and bilingual warning signs; vendors stood behind haphazard barbed wire or sat in makeshift wooden booths selling cigarettes and sex paraphernalia, eating and drinking tea.

Though I never set foot in Burma, the impressions of its people and flavors lingered. What’s the word for wanting to return to a place you’ve never been? The closest I’ve come since were restaurants in San Francisco, Seattle, Chiang Mai, and now, Phnom Penh.

My eggplant dish is gone. I return to three final bites of salad, an explosive combination of fermented green tea leaves, crunchy nuts and seeds, fresh tomatoes, a cocktail of pastes and oils, and a few critical splashes of pungent fish sauce, a condiment akin to an ugly dress that looks great when you put it on. By now, the restaurant is buzzing and every table is feasting on Burma’s national dish. I’m tempted to order another but remember the forthcoming beverage.

Even as a former British colony, Burmese tea culture is distinctly Burmese. Teahouses are gathering places, where customers sit around low tables and tea masters know their preferences—more or less strong, milky, sweet—and where government spies clandestinely monitor patrons for conversations considered subversive. While I wait, I read Finding George Orwell in Burma, in which Emma Larkin traces the imperial policeman-turned-author’s years in Burma from 1922 to 1927.

My tea arrives. It’s perfectly milky, without sugar.