Trekking in India’s most remote river valley.

The valley of the Shidi River occupies the easternmost wrinkle in India’s scrunched-up forehead, the Himalayan range. Thick jungle covers slopes that rise from its banks, and around its headwaters, to ridgelines that delineate the border with Myanmar. Fenced in to the north, east, and south by those geographical and political boundaries, the river rushes west, aimed at the vast drainage of the Brahmaputra basin. If borders were visible from the air, the Shidi Valley would appear like a dark green finger, jutting out of northeastern India and pointing at Myanmar.

When dozens of families fleeing unrest and famine in Myanmar macheted their way into this valley in the 1950s, both India and what was then called Burma had already become independent states, but the border between the two had yet to be drawn. These migrants, belonging to the Lisu tribe (later given the exonym Yobin in India) found only the scattered, stateless settlements of Lisu forerunners who had arrived just a few years earlier. Before those initial incomers, and stretching back through time immemorial, the valley had only hosted temporary visitors: hunters; purveyors of jhum, an age-old slash-and-burn cultivation that shifts from year to year; and the occasional itinerant priest or monk. No records exist of any visit by a British, Indian, or Burmese representative of a state.

But in 1961, 14 years after India’s independence, the Indian army did finally reconnoiter the valley, and nine years after that, India and Burma agreed to define their border, if only with lonely stone pillars placed hundreds of miles apart. For those Lisus who happened to live within India’s new valley, their “discovery” and subsequent envelopment into India marks the beginning of a perhaps inevitable tryst that even the most remotely situated peoples must have with statehood.

The valley is home to what are probably the most remote villages in India.

The first time I heard of the Shidi valley, albeit indirectly, was from a wizened old man in another valley, the Dibang, also in Arunachal Pradesh, a boomerang-shaped Indian state that abuts Tibet and northern Myanmar. The Dibang is remote, but unlike the Shidi, it has a road, electricity, and intermittent cell phone reception. As his grandson admired my friend’s camera, he put his hand on my shoulder and asked me a question with a sly look on his face.

“This boy keeps dreaming about what happens in Guwahati,” he said in Hindi, referring to northeast India’s biggest city, a smoke-choked urban nightmare a dozen hours’ drive from where we sat. “But no doubt people in Guwahati watch Delhi and Bombay on TV and dream about life in those cities, and then those city people must also be thinking about how it is in your country. And now you, here, came to find what?”

My response might have been incoherent because of my middling Hindi skills, but more likely because I’m not exactly sure what force attracts me to remote places, to seeking knowledge in the nooks and crannies of relative statelessness, to idealizing the isolated, the supposedly wild and natural, the flipside of my suburban upbringing. When I managed to mutter something like, “Cities are very polluted, and I don’t like how concrete looks, so I try to go far away,” the old man gestured vaguely at the layers of green, pyramidal peaks vanishing towards the east in the midday haze and said, “Then you should go there.”

Weeks later, on Google Maps, I determined that “there” was, unofficially, the Shidi valley.

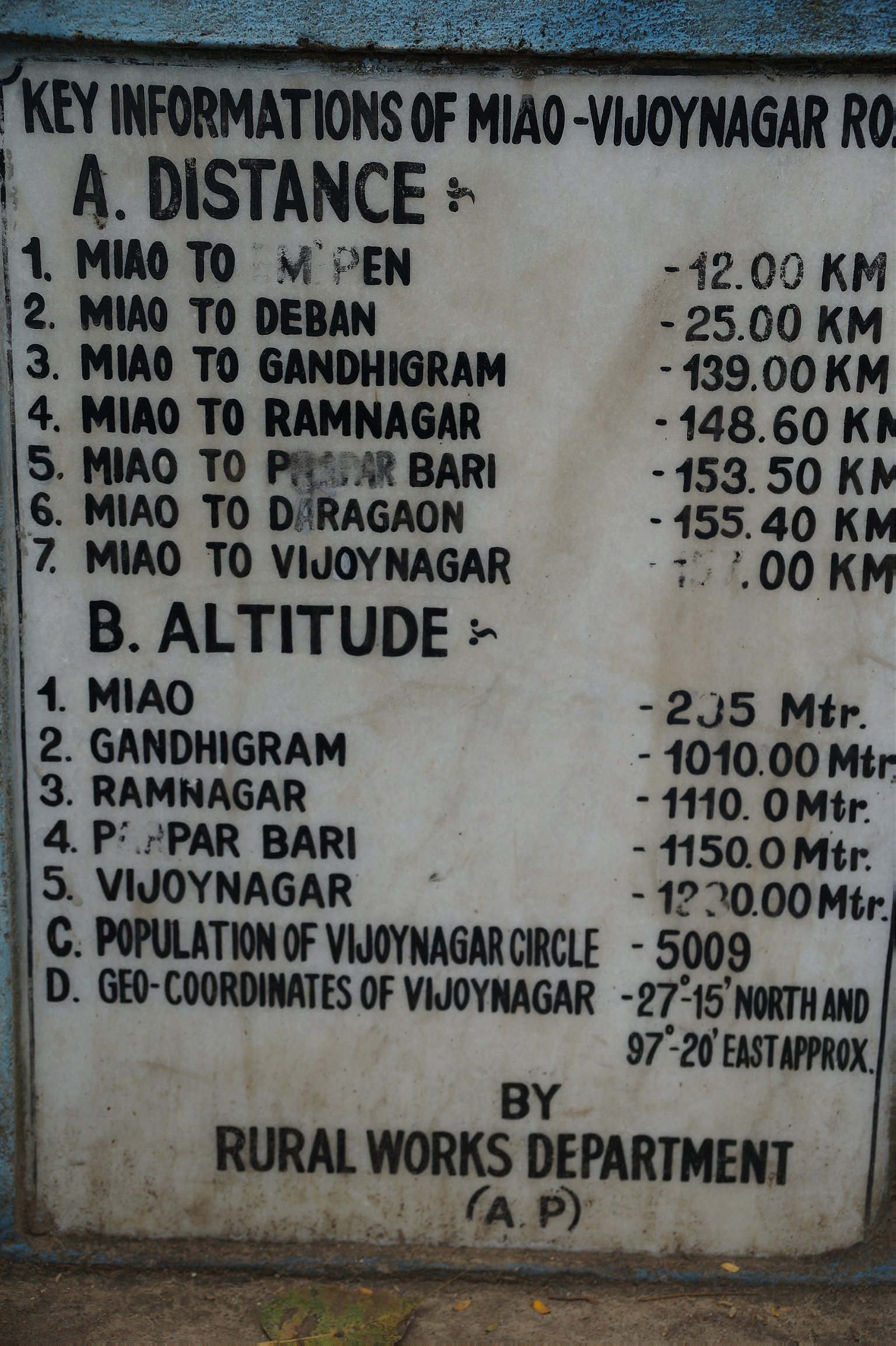

The valley is home to what are probably the most remote villages in India, if we measure remoteness by distance from a motorable road. Upwards of 5,000 people live the better part of a week’s walk from the nearest road in Miao, where the river meets the plains. To reach the most distant villages, one must follow muddy footpaths that cross jungle-darkened hills and vanish along slippery creek beds, then along the rock-and-driftwood-strewn banks of the Shidi River—and further, traversing its tributaries on handmade bamboo bridges for almost 100 miles.

As I walked up the valley, I asked the older Lisus to tell me how their lives changed when they suddenly became Indian. What I heard was a particularly sub-continental catalogue of promises and pitfalls, in this land where democracy and affirmative action for Lisus and other minorities are enshrined, yet simultaneously, remoteness is often a pretense for impunity and neglect. And while the Lisus I met on the way to the valley’s end seemed healthy, content, and at least mildly keen on being Indian citizens, their histories of the valley seemed to err decidedly on the pitfall side, with promise only recently becoming apparent, more than five decades after the Indian tricolor was first planted along the banks of the river.

The river flows through one of earth’s eighteen “biodiversity hotspots,” according to UNESCO, and the virgin jungles that enclose it host 600 species of orchid, 400 of fern, India’s only ape, the Hoolock Gibbon, and five species of endangered big cats, to name a few of the undeniable criteria it meets for deserving conservation. Given the region’s miniscule human population, it made for an ideal location to create a national park, and only twenty years after the Indian army first ventured into the valley, Namdapha, India’s second largest national park was christened and opened.

Life was simply arduous.

But back when Latchi Yobin was a young woman, and her family and six others made it to the Shidi valley in the early 1950s, the valley wasn’t just more or less empty; it was unknown to the Indian government. Together, the troupe had just escaped a truly fragile existence in northern Burma, where Lisus were essentially unwanted refugees, and traded it for a slightly less fragile one of hunting, foraging, buffalo raising, and gardening in what they saw as a place to make a new beginning, protected by miles and miles of jungles and hills between them and wars and famines in Burma at the time. Still, scarcity of food, tempestuous weather, and a cast of dangerous animals circumscribed life into survival mode here too. Life was simply arduous; besides dangers close at hand, older Lisus remember having to traipse through the jungle for more than fifteen days just to procure essential but unavailable items, primarily salt, from faraway towns.

That secluded existence, reminiscent of how people lived in times before nations, came to an abrupt end in the summer of 1961. Major General A.S. Guraya of the Assam Rifles division of the Indian Army, accompanied by around 30 soldiers, a fleet of porters, and two interpreters from outside the valley, arrived in Latchi’s village and, like the Czar’s men did in Anatevka in Fiddler on the Roof, told her and her kin that they were to be ready to leave their village immediately, or else. Latchi remembers the soldiers shooting several livestock to make sure their seriousness was understood.

In the coming weeks, all the Lisus in the valley were herded at gunpoint towards a village in a wide floodplain that they knew as Shidi, like the river. Once assembled there, they were told, “This place is India, and you are Indians,” Latchi recalled. Through the interpreters, the army men assuaged their fears with pledges of regular rations and road connectivity—promises of dependability given to a population that craved it, but knew little of the possible perils of dependence.

Meanwhile, the Indian government distributed the newly occupied land beyond Shidi to retiring Gurkha regiment soldiers and their families, who had been recruited from Nepal decades earlier by the British colonial army. As if taking a page out of the conquistador’s manual, Guraya then renamed the old Lisu villages Preetnagar, for his daughter Preeti; Ramnagar for his younger son Ram; and finally Vijaynagar, for his eldest. In Hindi, Vijaynagar also means “victory town.” Shidi village was—sincerely, I’m sure—renamed Gandhigram, in honor of India’s pacifist icon who held hallow, above most else, respect for decentralized power and village autonomy.

Adu Yelimi, now pushing 60, remembers that when his family first arrived there, Shidi wasn’t the town it is now, decades of settlement later. “A tiger might come to your field and eat your animals and you’d be scared to go out for many nights afterwards,” he said. “You could hear the elephants out back while you tried to go to sleep.”

But then a “Kheti Babu” came and taught them how to plant rice, said Adu, using his term for a representative from the Department of Agriculture. Rice is easy to grow, and one harvest can provide a family with a year’s sustenance. By cultivating rice, one can in turn cultivate a sedentary, stable lifestyle, living in cleared flood plains with fellow rice growers whose collective presence keeps wildlife at bay.

Adu, like many older Lisu, remains proficient at hunting and foraging, and he knows all the tricks one must use to test whether a mushroom is poisonous or not. But he remembers the monsoon season, decades ago, when the inherent insecurity of rice dependence was proven with alarming force. Dozens, or perhaps a hundred paddy fields including that of Latchi’s family were swept away by the Shidi River after heavy rains, and with their fields ruined and the fertile land up-valley from Shidi allocated to the Gorkhas, the affected moved downriver, only to soon find themselves boxed in ever further.

By 1978, Latchi’s family had settled in a downriver village called Nibodi. The adults of the village were summoned one day that year to Vijaynagar, a few days’ walk, ostensibly for what she remembers as a census count. While in Vijaynagar, a group of breathless young boys from Nibodi arrived, having sprinted the whole way to bear devastating news: Forestry Department officials had burned the village, with only the children and the elderly there to witness it.

Without the consent of the Lisu, the Indian government had decided to designate the rivers and mountains between Shidi and Miao—almost all of the remaining Lisu land in India, as far as they were concerned—as part of Namdapha National Park. As such, human settlement in those areas was made illegal. Those whose homes in Nibodi were reduced to ashes moved back to the only place that was left for Lisus in the valley—Shidi.

Unswayed by threats of violence and arguments for conservation, Latchi’s family moved back to Nibodi only two years after it was burnt, if anything, she said, for pride’s sake. Latchi claims to be 105 years old, but the contours of her memories place her at a more believable 85. When we met, in Nibodi, she told of her accumulated distaste for the Forestry Department officials with increasing vigor, chuckling at what now seems to her like the distant past, but practically spitting as she emphasized certain points. We sat around a fire, and floating pieces of ash were falling into her hair.

“Ten lakhs is nothing for this fertile land,” said Latchi, referring to the amount of money the government is willing to pay to resettle those living in the park on land outside of the valley, about $16,000. “Money is of no use anyhow. My husband is buried here. I will be too.”

Park officials blame the Lisu for cutting too much firewood from the forest, and for widespread poaching that has depleted wildlife. The latest tiger census, done by remote camera sensing, only captured four tigers though there are certainly more that didn’t happen to cross the cameras, said Dusu Shra, the park’s current field director. Most Lisus admit to hunting, but deny poaching animals like elephants and tigers, and without a road upon which cooking gas can be transported, Lisus use wood from the jungle for all heating and cooking. Park officials want the Lisu out.

Few, if any, want the resettlement money, and feel that Namdapha is rightfully Lisu land. At a meeting last November between national forestry officials and Lisu representatives, the additional director general of India’s National Tiger Conservation Authority’s, Rajesh Gopal, gave his tacit agreement to the stalemate when he promised, “Hum aur jabardasti nahi karenge.” We won’t do any more silly business, using a choice Hindi euphemism for forcible evictions.

Thus confined to a few villages near Shidi and illegal settlements in the national park, the Lisu have had to fashion lives that rely on forces beyond their valley, if only because arable land is becoming more and more scarce. Yet, despite the rocky history, everyone I met welcomes the opportunity to incorporate further into Indian markets and government welfare programs. If the alternative is returning to the fragility of living in a jungle that, in the grand scheme of things, they have only just begun to inhabit and understand, then the broken promises of the Indian government are but postponements of a long-awaited inclusion into Mother India’s reputedly caring embrace.

That caring embrace is visible to Lisus who make the walk down to Miao, or travel further. In that India, everyone seems to have access to schools, hospitals, roads, subsidized rations, and, if they belong to a registered, or “scheduled” tribe, they are reserved quotas for educational and employment opportunities, and can get certificates of ownership for their land. All of which would be beneficial should they actually receive those things—but as those of us who live in the unwieldy yet accessible parts of India witness constantly, being afforded a right scarcely translates to being availed it.

Fifty-four years into their tryst with India this year, the process to bestow scheduled tribe status to Lisus began in February. For decades, other tribes have argued that Lisus are more like refugees, who don’t truly belong to India, and don’t deserve a piece of its affirmative action pie, despite ample evidence that Lisus arrived in the valley before the Indian state even existed. In fact, Lisus were only made citizens by the federal government in 1994, after they were mistakenly left off the legally recognized list of tribes in Arunachal Pradesh in 1979, around the same time the plans for the national park were solidified and Nibodi was burned.

With scheduled tribe status, the Lisu will be able to claim what land they have left outside of the national park as their own. It is perhaps the only reason they can be happy that the promised road has still yet to be built after all these decades—otherwise, scheduled tribes from other valleys could have easily moved in and claimed it themselves.

The government has, for the third time since it drew the valley’s borders with Burma in 1972, commissioned the building of the road. The first two times, it was blocked by landslides or ruined by rains within a month of its opening. The last time it opened was in 2011, and in just 4 years, jungle has reclaimed it to the extent that paths cleared by machete in the jungle are often more efficient to travel on. This time around, the Lisu have submitted an appeal to their state government to give the building contract to the BRO, or Border Roads Organization, run by the military, which has an excellent track record.

But on one stretch of what’s left of the previous road, I ran into a group of sunglass-wearing, pot-bellied men taking selfies who said they had won the tender for that particular stretch. “Someone else has the tender for the rest of it—we are only building from here until 40th mile,” one of them said, refusing to give his name. I asked what company he worked for. “It’s a local company, sir, you wouldn’t know it.”

In Shidi, Phusa Yobin, the 66-year-old president of the Lisu Welfare Committee, said that the company belonged to a relative of a member of Arunachal Pradesh’s state assembly, and that the other two companies that won tenders for the rest of the road were tied to even higher officials in the state government. Without the BRO, Phusa said, he doubts the road will last any longer than the last ones, especially with it being done by separate companies with no vested interest in maintenance.

It seems safe to say that until the BRO steps in, the Lisus, young and old, will continue to walk for days and days to towns more firmly in India’s grasp to secure those things which they believe will improve their lives, and which are light enough to carry on their backs: tin for roofing, metal hooks for fishing, solar-powered lights, medicine, car batteries to power and charge electronics like tiny TVs and transistor radios. As one Lisu woman named Chamahey Ngwazah put it to me, “We’ll still need to do left-right-left all the way there and back.”

I’ll admit it: having escaped the crumble and clog of India’s plains again, I worry that if the Lisu get their wish, and the BRO steps in, trucks brimming with sacks of concrete and instant noodles and cheap cigarettes will trundle up to this utmost remote place. But the desire to finally be connected to India is palpable. At some point beyond the thirtieth mile of walking, I was overtaken by a man doing left-right-left, carrying a satellite dish on his back. It was the same dish I later saw in front of Phusa’s house and a good number of others in the villages. They all were made for Dish TV, an Indian company. And displayed on those strange grey orbs, installed in front of the thatch-and-bamboo homes of people forgotten by the rest of their country, was that company’s pompous Hindi slogan—Ghar aayi zindagi. “The world, brought to your home.”