As an angsty 25-year-old, Jeremy Hartley found a home in Bangkok’s thriving punk scene by grabbing a guitar, writing some awful lyrics, and starting a band.

The band was packed tight in a taxicab rolling down Bangkok’s Sathon Road when our song “Far Away” started playing on the radio. The four of us—Arm, Matt, Tat, and I—were headed to practice across the river in Khlong Ton Sai, and Tat, with the natural superiority of one born into a high-class Thai family, had asked the driver to roll the dial over to 104.5 FM Fat Radio, the local indie station, in the hope that our punk rock doo-wop single would come on.

The driver didn’t speak English but he had to have sensed something special was in the air. When the song started, the four of us broke up laughing and swearing, and Tat asked the driver to turn up the volume.

It was a lot to take in. A radio antenna on the hood of a Bangkok taxi had funneled the contents of an invisible wave down from the city’s smelly air. And what messages did that wave bear? Arm’s drum lead-in. The guitar solo Tat had conjured on the day we recorded. Matt’s bass line. And, finally, my off-key voice, laboring through the crude lyrics I had composed more to give form to my unmusical bellowing as I bashed on my own guitar than to make an aesthetic point.

Remember when we took a walk?

Remember when we danced?

Remember when I got so drunk I pissed my pants?

The parts were just as we had recorded them in a cigarette-and weed-smoke choked house weeks before. But in that moment in the taxi they all sounded bigger and more cohesive than they had in any previous playing. “Far Away” had ascended into the empyrean and become four minutes and 12 seconds of proper radio music, flying around in space where anyone could hear it.

We were The Darlings, and our song was on the radio.

This constant, overwhelming mindfulness couldn’t last

I moved to Bangkok from Chicago in April 2001 because I wasn’t satisfied with my life as a 25-year-old in America. George W. Bush had just become president and, somehow, I was able to survey the third-largest city in the richest country in the world, with all its music and comedy and art, and find no salve for my angst.

Heading to Asia temporarily put an end to all that. For my first few months there, every experience was heightened. Each trip to 7-Eleven for a tub of yogurt or a hot dog was a dip into pure being. The clerks remember me from when I came in yesterday for a hot dog. A Thai hotdog. This is the intensity of life!

My fits grew more emotional when I figured out how to buy fruit from street vendors. But this constant, overwhelming mindfulness couldn’t last. I’m no monk, and my soul could draw only so much nourishment from street-cart pineapple slices.

Within months, I started missing the pop culture that I had taken for granted back in Chicago. Pirated DVDs meant I never had to forego the familiar pleasures of Hollywood in Bangkok. Too hot to go to the pool? It was never too hot for Bobby DeNiro in a knock-off copy of Heat. But music was a problem. Back in the U.S., I would see punk and indie rock shows several times a month and had even brought several hundred CDs and a Discman with me to Thailand. When the polite murmuring of my fellow Bangkok Skytrain commuters was too much with me, I could turn to a Slayer or Suicidal Tendencies CD for comfort.

I needed live shows and was keen to embrace Thai music—which is to say, Thai bands playing globalized Western genres such as rock—but I couldn’t figure out where to find it. There were no well-known venues. I would go for a beer at a luk thung country music bar only to find my thoughts drifting toward distorted guitars and Billy Idol sneers. I was a dark, Hamlet-like presence amid the pure joy of the dancing folks around me. I might clink whiskey glasses with them and slap a few backs, but I always held part of myself back.

I saw a lady in an office wearing a shirt with the word “Vagitarian” on the front

I missed the old stylized cynicism of punk rock. I was certain there had to be an underground rock scene. Globalization had given the people of Bangkok donuts and candy-flavored lattes. Why should they not also have Minor Threat and The Misfits? And I had seen kids in punk t-shirts. (Though I also learned not to take people’s t-shirts too seriously there: I once saw a lady in an office wearing a shirt that had the word “Vagitarian” printed on the front.)

And I had heard that back in the mid-1990s, when Thailand was one of Asia’s booming economic Tigers, there were enough rockers in Bangkok to draw performances from famous American bands such as Sonic Youth, Weezer, the Beastie Boys, and Green Day. Some key local indie rock bands, like Modern Dog, for a while considered the Thai Radiohead, had also got their start around that time. But then the Asian Financial Crisis hit. The destruction of so much wealth didn’t leave a lot of baht leftover for seed capital for a Southeast Asian CBGB’s.

So I searched.

One night I was out draining cheap beers on Khao San Road, Bangkok’s famous backpacker street, when I spotted a skinny Thai guy with tattoos and a Mohawk. I grabbed him and started gushing about how I, too, was a punk rocker. I breathed a series of beery questions into his face: What bands do you like? Are there any bands here? Where do the rockers hang out? I shouted, relying on the alchemy of loudness to transform my slurred English into something a non-English speaker could understand. The punker was shy in a Thai way but a good sport. He signaled that he knew a bar I might like and offered to lead the way.

Our destination: Immortal Bar.

Immortal sat at the back end of a mostly empty commercial building in the middle of the carnival of Khao San. Inside were a few travel agents on the ground floor near the front of the building and a broken-down escalator that led up to an empty second floor. A lot of buildings were in such disrepair in the years after the Asian Financial Crisis.

Behind a graffiti-covered door at the back of the building was a large dark room with a 20-foot-high ceiling and rough stone floor. A bar sat near the door and to the right was parked a decommissioned tuk-tuk that housed the DJ gear. The music was heavy and too loud for conversation.

Between five and 10 people sat soaking in the heavy metal ambience.

I grabbed a beer and kept an ear cocked, smugly inventorying my disapproval of the DJ’s song choices. Rock rap? Oh boy. My mind wandered to my stack of CDs.

Fah was the owner. With a lot Beer Chang bravado, I told him I was no mere backpacker and demanded that he give me a shot in the DJ tuk-tuk. I started bragging to him about how great my CD collection was. This was before the days of fast music downloads, and the prospect of having some new music to listen to was kind of a big deal. Fah said he’d try me out.

Fah had a mischievous face and waist-length dreadlocks. He looked like Max Cavalera of the Brazilian heavy metal band Sepultura, and I would learn later that this was no accident. Fah professed a pan-third world nationalism inspired by Cavalera’s incorporation of Brazilian folk instruments into his own band’s music. Fah played in an “extreme metal” band called Plahn and had visions of taking this Western form and making something uniquely Thai of it. He spoke decent English and would ask me about Western metal’s preoccupation with Satan. Fah said he didn’t know Satan. He knew Buddha and had no problems with him. (I’m not sure I was ever able to parse such theological distinctions in Plahn’s music.)

No payment, but I could drink as much Beer Chang as I wanted

My first night in the DJ tuk-tuk followed a shift at the newspaper where I worked as a copy editor. I was wearing khakis, a sweaty button-down shirt and brown saddle shoes. My glasses were steamy from the humid air. I looked like a Sunday school teacher.

Fah had gathered a group of dignitaries from the local punk and metal scene at a small table at Immortal. They were working through a bottle of Sangsom, a Thai version of rum, with soda water and Cokes and seemed eager to know more about this bald guy in business casual attire.

I was more nervous than I had been on the first day of my day job. I gave them several hours of my best punk and metal, occasionally drawing a few claps from Fah’s table, and when it was all over Fah invited me over to drink and make our arrangement more formal. He said I could play every night but Friday and Saturday, which were reserved for the club’s main DJ, a shaven-headed young guy named Kai. He couldn’t pay me, but I could drink as much Beer Chang as I wanted. That sounded good to me.

I would spend almost every night at Immortal for the next year or so.

They all looked the same in their fisherman’s pants

The bar drew a mixed clientele of foreign backpackers and Thai rockers. I studied the foreigners and soon acquired a jaded disdain of their backpacker-ly affectations. The sun-burnt Brits, the Israelis just done with their military service, Japanese hippies—they all looked the same in their fisherman’s pants and free-spirited holiday cornrows. They were in Thailand seeking the possibility of adventure but were also receptive to the soothing familiarity of the Western music.

I judged their clothes and their behavior from the safety of my tuk-tuk, but I was just like them. I had taken on the airs of seedy hostel owner sneering at his clientele.

I was much more emotionally honest toward the locals. Occasionally, when they could put a little money together to spend on Cokes, a group of teenage “street punks” with Mohawks and leather coats with patches would stop by. (These punk signifiers were strictly rote: It couldn’t have been easy to wear leather in the tropics, but they did it anyway. And one of them once spent an evening trying to explain to a French backpacker why Thai punks can like the song “God Save the Queen” and still love their king. No Bastilles were stormed that night.)

I would watch them, hoping to please them with a well-timed musical selection. Nothing made me happier than when they started chanting “Oi! Oi!” in time with the music.

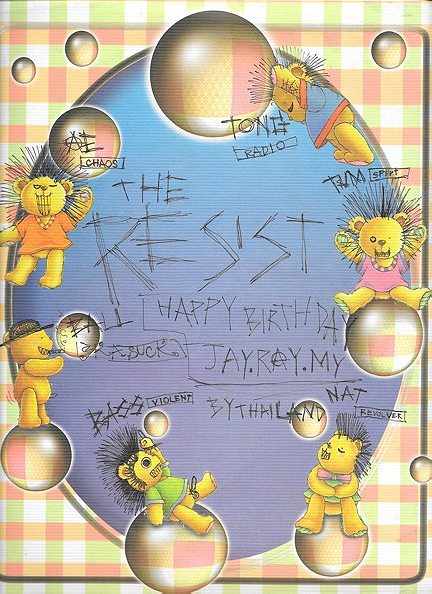

For my 26th birthday, the punks pitched in and got me a birthday card featuring a group of teddy bears on which they had drawn Mohawks, tattoos, cigarettes, middle fingers, and erections.

Later that night, a friend gave me some ecstasy, which I’d never tried before. I wandered Khao San clutching the punk rock teddy bear card to my chest and telling anyone who would listen that I loved the world and had finally come of age emotionally.

The only person to express anything even remotely reciprocal was a transvestite who pawed at my reproductive organs as I eased through the crowd at a bar. Feeling the hand cupping my genitals was like experiencing an electric shock and I dropped my punk rock teddy bear card on the floor. I was so focused on saving it that I scrambled roughly among the other patrons’ legs until I had retrieved it. I still have it.

The demands of commerce ended my tenure at Immortal. Fah had wanted to turn the place into a live venue for local metal bands, but couldn’t host regular concerts because of an anti-noise ordinance. Also, he couldn’t pay rent off the income from the cheapskate metal dudes and punkers who comprised the infrequent clientele. Eventually, he started having hip-hop nights and brought in DJs able to drive backpackers into orgies of awkward grinding. Fah reckoned such types would also being willing to spend on drink. They did.

My own hip-hop collection was too weird for parties, so I had to give up my spot in the tuk-tuk. I didn’t mind, though, because by then I had already become friends with the members of what would become my band.

Tat’s family’s maids would bring fresh ice for our drinks

Tat was a college friend of Kai and would come by when I was DJing. He was half a year older than me but had the build of a ‘tween and, by some quirk, a handful of the mannerisms of Dave Chappelle. It could have been all the weed he smoked. (He’s also the source of my favorite statement on beer. He was pressuring me into drinking one night and said, “Come on, have a beer. It’s cold and you know what it tastes like.” Budweiser, are you listening?)

Tat was insanely passionate about music. He had spent some time in Tennessee as a student and had a deep love for independent rock music, the more obscure and lo-fi, the better. If you’ve a recorded a couple fuzzy ballads in your closet in Glasgow, Tat has heard of you and probably has your 7-inch.

We shared a love of guitar-heavy power pop and would spend many nights drinking whiskey and spinning records at his home. His family was well-to-do and his house like a museum, packed with ornate furniture, plants, and pictures of his police general father kneeling before the Thai king. Each of the rooms was like a separate apartment, and it was rare to bump into one of his brothers or a parent while visiting. Tat’s room was like a little rock temple—he had a hi-fi system, stacks of records and CDs, and a computer perpetually linked by dial-up to peer-to-peer music-sharing programs.

During our record-spinning parties, his family’s maids would bring fresh ice for our drinks, crouching low to ensure their heads always stayed beneath ours, even if we were sitting on the floor, in a sign of deference. It made me uncomfortable and I tried to out-defer them by slouching. This only made them draw lower to the ground. Seeing the discomfort I was causing, I realized it was better to make peace with the local class system and focus instead on giving hearty thanks.

Many truly great bands have started with less

After many nights singing along with his Ramones records, Tat and I decided it was wrong to continue denying the public access to the talents we imagined we possessed. It was time to form a band. We both could handle guitars well enough to bludgeon our way through three chords’ worth of music. And we were enthusiastic. Many truly great bands have started with less.

I was a little worried about how little we knew about amplifiers and other parts of live performance. Luckily, I had an ace up my sleeve in the form of my childhood friend Matt.

Matt was the reason I moved to Bangkok. We grew up together in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, becoming friends at the age of eight when we realized we both had an adult command of vulgar language. Our schoolyard swearing sessions would lead to other adventures—fort-building, ice-berg sailing on Lake Michigan, skateboarding, and early explorations of punk rock and heavy metal. He had moved to Thailand a few years before me and helped me land the newspaper job.

Matt was always good at finding ways to exercise his passions. In his words, he was a “steely eyed missile man.” We both played in our high school marching band, but Matt had a genius for music and an intensity that allowed him to practice for hours at a time. When we were teens, he got his hands on a Sears-brand guitar and within a couple years he could easily switch back and forth between complex classical pieces and mind-melting Steve Vai-style guitar heroics. He could also handle amplifiers and the rest of the relevant apparatus. We had always dreamed of forming a band, but there was no music scene in Northern Michigan.

We went our separate ways during college, but our old habits kicked in after reconnecting in Thailand. Matt would come by Immortal as often as he could stand (the music really was too loud) and we would occasionally dust off the band talk.

But it wasn’t until Tat and I started writing songs that things came together. I asked Matt if he’d mind playing bass for our band since Tat and I had already bought guitars. It was a criminal waste of his skills, but he agreed. Next, we just had to find a drummer.

Tat and I knew of one possibility from among the regulars at Immortal. The members of a ska-punk band called Adulterer used to come by to nurse a bottle of Sangsom. They were laid back and spent more time hanging out than practicing or playing music. There was one dark presence, though.

Arm was their drummer, and was usually out with them, though he didn’t drink. Drinking made him violent. Arm struggled with a desire to fight that he had fully indulged as a vocational school student (school rivalries in Bangkok often devolve into full-on gang warfare). Legend had it that as a teenager, Arm had been wrapped up with a school gang that was selling handguns. During a deal, things went south and a fight broke out. Arm allegedly grabbed a machete and hit a guy on the arm, cleaving it off. People said his mom had had to buy him out of jail. I was never able to figure out how true any of this was. Everyone whispered rumors about this incident and made sure never to make Arm mad.

By trade, he was a baker and worked for several of Bangkok’s international hotel chains. He could knowledgeably discuss a variety of pastry types and would complain about the quality of local croissants. For friends’ birthdays he would bring eight-inch tall cheesecakes, festooned with the finest chocolates and preserved fruits available in the hotel kitchens in which he worked. He was fiercely loyal but still shy with friends. It was incongruous, but a few shots of whiskey would have him kicking over tables.

So far as I know, Arm taught himself to play drums by banging on buckets and other surfaces, and his sets with Adulterer were something to behold. He looked angry even when he was playing a goofy ska song. I figured he’d be perfect for what Tat and I were cooking up. (I was right.) Plus, I sensed Adulterer’s mellow collective life was nowhere near intense enough for someone of Arm’s angry disposition, and he’d probably be glad to have another outlet for his drum playing.

We asked if he was free, and he said he’d be glad to sit in.

Our first concert was at a girly bar in Bangkok’s red light district

We blundered our way through a handful of songs in weekend practice sessions at a studio across the river from Bangkok. The owners didn’t like us playing loudly, though it was our default approach. We didn’t understand the equipment well enough to get good tones out of it, so we just made everything louder. They would let us know if the volume was disturbing the people in the other rooms.

Unfortunately, there were no outside powers to help us with the internal dynamics. We were bosom chums when passing around a Sangsom bottle, but things could get difficult during practice sessions. Matt would get bored with Tat’s inability to tune his guitar. Arm would get sick of having to learn another mid-temp song that I unconsciously ripped off from Weezer (though I also think that one’s our best song, despite the terrible singing). I would get frustrated with anyone whose enthusiasm seemed to flag. And we were all embarrassed by how hard it was to accomplish even the most basic feats of musical composition.

It is amazing that an undertaking as humble as punk rock could cause such strife. We weren’t The Beatles and had no illusions about being talented. Still, each practice session was a trial. The fact that we weren’t particularly good at playing music and, frankly, looked strange performing together is what inspired our name. The Darlings. It conjures images of sweetness and light. Instead, we were two old-looking white foreigners, an angry Thai guy, and what looked like a young Thai boy with weed-reddened eyes. What a letdown. And letdowns are kind of punk, right?

So we pushed ahead, and slowly some songs emerged. We rallied around them and even as our affections for one another waxed and waned, we were soon ready to play in front of an audience.

Our first concert was at Paradise Disco, a girly bar in Bangkok’s notorious Soi Nana red light district.

My friend Stirling, the bassist in another Bangkok band called the Eastbound Downers, was launching a concert series to showcase local indie rock bands and was kind enough to give The Darlings a place on the inaugural roster. His choice of Paradise Disco for the first outing was inspired. He had tempted the frat-boyish American owner to surrender the premises with visions of young hipsters delivering better drink receipts than the usual discrete pairings of old white men and young Thai ladies sipping cheap bear and small Cokes. I don’t know that the business dynamics worked out—the owner would later saddle his hopes for the bar’s future on a mechanical bull—but let’s give Stirling his due: He arranged a concert at a seedy bar in the middle of a neon-lit village of nudie bars and brothels. It was like something from the fever dreams of a young Axl Rose.

A decent crowd came that night, including many of the Mohawk punks from Immortal. Even though they were intimidating in their leather and spikes and patches, most of them were too shy to have ever walked through Nana on their own. Seeing big gangs of Mohawk punks preening and smoking outside of Paradise, I sensed they enjoyed freaking out the bar girls and their Johns. The reactions probably weren’t that different from what they’d have got at a church picnic. The behavior in red light districts sticks within fairly predictable boundaries, so it’s fair to say a relative conservatism prevails. And there’s nothing punks love more than tweaking norms.

We were nervous as we took the stage. I leaned toward the microphone and said, “Hi, we’re The Darlings,” and started in on the opening riff of our first song. In my excitement, I played it two or three times faster than we had ever practiced it. I could see Matt had given up on playing with a pick and was punching his bass with a closed fist. Arm was panting with the effort of keeping up.

Our set was over quickly. I was pleased that a few of the punks had danced during the show. From the stage, it felt like a scene from a Mötley Crüe concert video. Later, I saw some video footage captured by a German documentary filmmaker who had happened to be there, and it was clear the dancers were really few in number.

Arm would have an apocalyptic meltdown if we had to wait

Other shows would follow. In the absence of a regular venue, we played in bars and restaurants and even grabbed a spot at a punk rock festival at the Queen Sirikit National Convention Center. I had once seen a performance of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute” there, and performing our own music felt iconoclastic. I had taken over for Papageno as the night’s comic oaf.

We shared stages with dozens of local bands—hardcore punkers License to Kill; pop punkers Stage Clear; rock gods Brandnew Sunset (who kindly named one of their songs “Jeremy Hartly” [sic] because I so admired the guitar fireworks starting at the four-minute mark); the impossibly cute Bear Garden—as well as some touring groups from Australia, Hong Kong, and Malaysia.

We were welcomed into the scene, but I suspect people also pitied us because of the mistakes we made. I wouldn’t be able to stop my guitar feeding back or my voice would be flat when I tried singing. Tat would bang his guitar against a mic stand, knocking it out of tune, but then couldn’t figure out how to fix it. Matt would decide he didn’t want to carry a bass to the show so we would have to ask to borrow one from one of the other bands. Arm would insist that we play first so he could go home early—and then have an apocalyptic meltdown if we had to wait.

In short, performing live wasn’t easy for us. We started to wonder if taking The Darlings into the controlled confines of a recording studio would be more supportive of our, ahem, art.

We enlisted Bank, a recording engineer and the front man of the strange rock band Red Twenty, to help us. He was running his own record label out of a dingy house and had arranged to borrow some drums and extra microphones to record us.

The night before we were due to start, Arm had gone to the studio to set up the drums. He hadn’t told the rest of us that he expected us to help, so it was a bit of a surprise when he called Tat around 10:30 p.m. and subjected him to an unhinged, expletive-filled rant about how we had let him down. We gathered in an emergency meeting at Tat’s house to calm everyone down and make sure things would move forward in the morning. The next day, Arm showed up with a homemade Japanese-style curry that he had made that morning, a spicy peace offering that we all enjoyed together.

The studio occupied two rooms. The drums were in one, and the second room was where Bank did all the recording on a desktop PC. He had hung heavy curtains across the entrance to deaden the sound. The rooms were air-conditioned but there was no ventilation otherwise. This proved a liability, at least to me. We were at the studio from early afternoon until late at night, and everyone was chain smoking. Tat and Bank also took multiple breaks throughout the day to roll and smoke thumb-sized joints. I would end up getting a case of tonsillitis aggressive enough to make a doctor gasp when he looked in my throat. That infected, pus-slicked throat is the one responsible for the voice on our CD.

We finished recording the next day, and asked our friend Daisy to do some artwork for us. Then it was all a matter of turning the audio and picture files over to the cheapest printer and assembler of CDs we could find. Within days, boxes containing several hundred Darlings CDs were ready.

We organized a CD release party and tried to sell copies whenever we played shows. And Bank was good enough to pass a copy over to the people at Fat Radio. After we heard our song in the taxi, we would ask our friends to call in and request The Darlings, falsely creating the impression that we were in demand. I can’t help but wonder now how many cab drivers might have heard it during the few weeks our single was in rotation.

I don’t know that the CD was available for sale anywhere other than at our concerts. Somehow it found its way onto Amazon, where one vendor was recently offering to part with a used copy for a princely $80.14. I doubt anyone has bought a Darlings CD off Amazon. I have no idea where the proceeds of a sale might go. We certainly don’t get them.

The Darlings’ career culminated at Bangkok’s 2004 Fête de la Musique, an all-day outdoor festival organized by the Alliance Française and some promoters from a music magazine. Somehow, The Darlings were selected to play alongside a collection of much more accomplished bands, such as Apartment Khun Pa and Futon. Easily more than 1,000 Thai hipsters, foreign backpackers, and curious old people had gathered near the stage, drinking, dancing, and churning up the mud left by the afternoon drizzle.

The other Darlings and I had watched a succession of much-loved performers take the stage and we prayed for the sun to set so our performance would look more professional by the grace of the stage lights. The dread of inevitability grew with every passing minute.

Around 8 p.m., we finally took the stage. Two MCs had been telling jokes and entertaining the crowd between bands, and the sight of two sick-looking white guys, a sick-looking Thai guy, and an angry Thai guy was irresistible. The MCs joked with us by pretending to introduce themselves in English: “Hello! Thank you very good!” The crowd thought it was hilarious.

I did my best to ignore them. I had brought a stack of Darlings CDs on stage with me, and while the MCs tried to interview a grumpy Matt, I threw copies out into the crowd. The people surged forward and jumped into the air trying to get them. Anything for a free treat.

One of the MCs came over and asked why I was giving away CDs. I said, “because I want people to like us!” It was supposed to come out as a joke, but it sounded pretty sincere thanks to my quavering voice. Anyway, I don’t think the MC understood what I was saying and no one in the crowd seemed to care. The excitement of free-CD time ended pretty quickly and it was clear everyone wanted to be entertained. Otherwise, why the hell were we wasting their time when they could be dancing to Futon?

The MCs left the stage. I gave my customary, “Hi, we’re The Darlings,” introduction and then we jumped into our first song. Thankfully, a burst of energy came up from the crowd that inspired us all. There were so many people dancing under the stage lights that they disappeared into a pogo-ing black mass beyond the glare’s reach. It was probably our best show, and I doubt I’ll forget it.

While some guys keep returning to that night of high school glory acted out on the football field, I know I will forever replay those first few chords of our opening song, “Who’s the Asshole?” They are my game-saving Hail Mary pass.

Illustrations by Ken Garing, author and illustrator of Planetoid. Follow him on Twitter at @ken_garing