I set out to write an honest profile of Shahid Kapoor, one of India’s biggest stars. His fans may never forgive me.

MUMBAI, India—

It was just after the power went out across the whole south of the city that the online hate against me really lit up.

As I stared at a silhouette of myself on a Mac screen gone dark, my colleagues at the GQ India office started to get up from their chairs, some cursing that the sudden electricity cut had robbed them of their best lede ever, some inquiring if we could go home now, and me wondering if this was the act of a benevolent God to save me from the torrent of all-caps abuse coming my way on Twitter.

I’d already been receiving tweets like “looks like your magazine has too much of empty space for you to waste… :)”, “never again i will read any article by@davebesseling,” “He doesn’t even know the J of journalism,” and “The writing skill of @davebesseling is as ugly as his face.”

The rest of the team milled about in an impromptu office-wide water-cooler conversation, as I, ever the masochist, opened Twitter on my phone. With each refresh, notification bubbles in the double digits popped up on the screen. Every tweet slandering not only the story I’d written, but my name and professional credentials, was being favorited and retweeted by a swelling mob of readers out for my blood. One tweeter preferred I handle the lynching for them: “U want to be famous….. Jst do suicide.”

You’d think I’d actually reported on something important.

As features editor at GQ India for the past year, I’d written all the original cover stories, the majority of which were au courant profiles of the subcontinental Alpha class that lords over Bollywood, the largest film industry in the world. Sounds fun, doesn’t it? It is, especially when you end up in a drunken late-night guitar battle with the Indian equivalent of Brad Pitt in his living room, and the Indian Angelina Jolie eventually has to come out and tell you to shut up she needs to get some sleep.

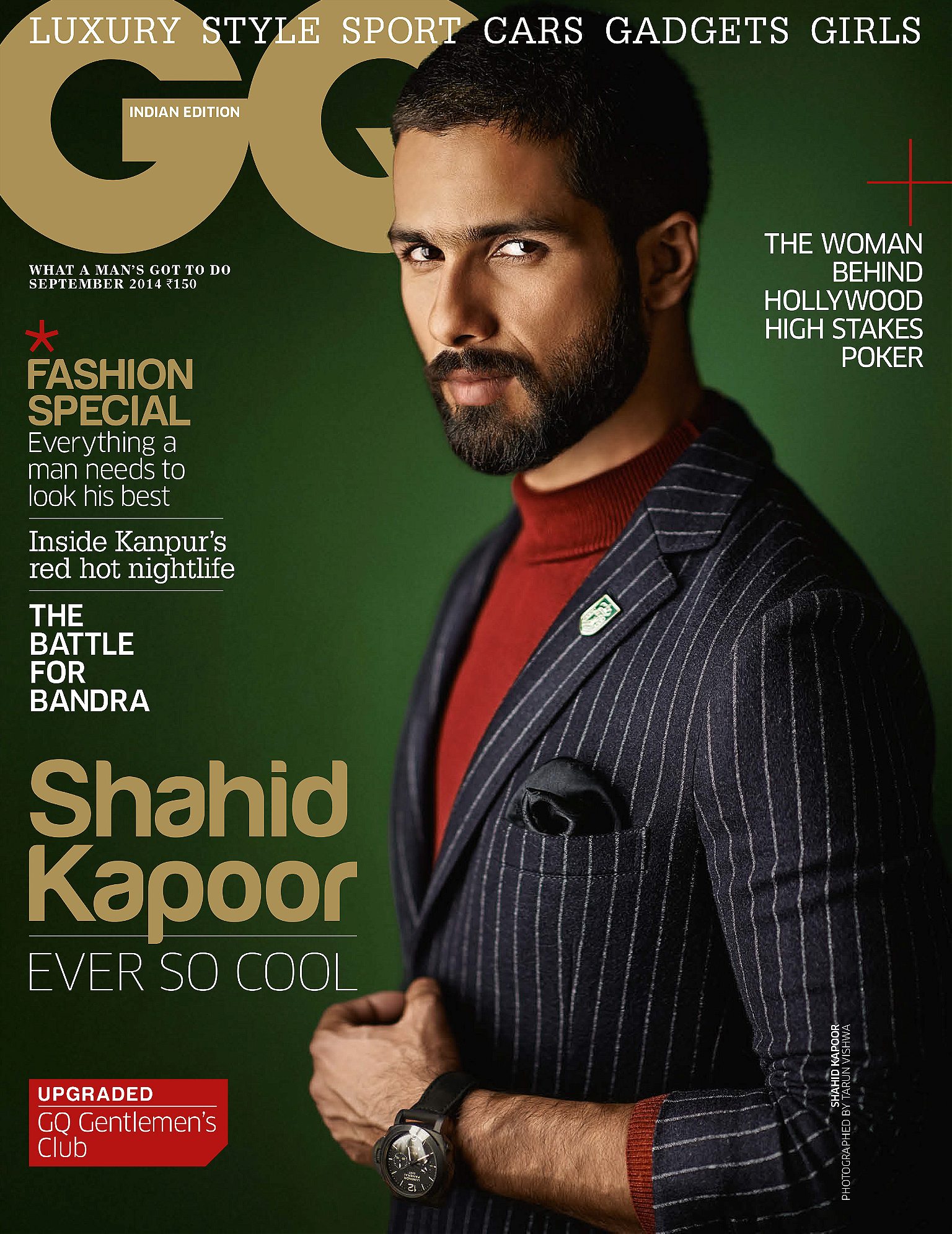

I’d pulled no punches with any of my celebrity subjects. I’d been happy with the stories I’d produced, especially compared to the usual sycophantic Q&As in the tabloids and the panegyrics in the weekend supplements. But none of my work had incited as violent a reaction as the September issue’s cover story: my afternoon at home with actor Shahid Kapoor.

Delhi-born, Mumbai-raised, 33-year-old Shahid told me he considered himself a dancer long before he thought about becoming an actor, and he appeared in a few music videos and TV commercials before his first leading Bollywood role in 2003. Since then, his career arc has been more like a series of peaks and valleys. He’s a could-have-been kind of superstar: still famous enough to buy a house with its own private dance club, but considered, artistically, as unleavened. Turns out some of his fans don’t see it that way.

“I request Shanatics to not to buy @GQ_India’s edition! We STRONGLY CONDEMN @davebesseling’s pathetic writing & we wont accept this to SK.”

What the hell did I say?

“#Shanatics Should Be United Against This Damn journo @davebesselingWho Doesnt Even Deserves His Job!”

And what the hell is a #shanatic?

Sitting in the dark at my desk, more mobile phone screens started to cast shadows. The office chattered. Power’s out all over town. Won’t be back on for the rest of the day. Does this mean we can go home now?

Before you make an India power-supply joke, the conceit around here is that south Mumbai is the one place in the country where the electricity never goes off. I’ve lived in a few other Indian cities where the first power-out lament is directed at Mumbai’s miraculously uninterrupted current.

Something was definitely wrong.

Several minutes later, sitting shotgun in my boss’s car on the way to lunch in Colaba, I began reading the Tweets aloud:

“Just read @davebesseling ’s intrvw in@GQ_India Felt like read some gossip girl’s blog. Such an unprofessional, cheap, disrespectful thing.”

“Interview of @GQ_India by@davebesseling is pathetic ! Will try not to come across ur work ever again. Your imaginations are worse Unreal.”

Our editor had decided to take the crew to a restaurant that we’d called and confirmed still had its lights on, and he was clearly amused at the reactions our cover story was getting on its first day after publication. I would have been laughing too if I wasn’t the one at the center of the storm. “What are they even mad about?” he chuckled.

“I don’t rightly know,” I professed.

As the hate continued to roll in through the appetizers, I began to understand. Shahid Kapoor, in the eyes of his fawning superfans, is a good, clean, Indian-made man-boy. And that’s what Bollywood provides to the young, the impressionable, and the bored. Man-boys. He sings, he dances, he smiles. You could bring him home to meet your mom in your traditionalist village.

We don’t like to assume that our ‘stars’ have sex

The escapism he and his Bollywood counterparts offer is without controversy. Or at least they try to keep it that way. With very few exceptions, any potentially raw subject is met with a reaction akin to a drop of rain on a convex mirror, to the throbbing consternation of anyone sent to interview them. This isn’t the U.S., where our brother magazine recently published a cover story that had Channing Tatum confessing to being more or less a functioning alcoholic. He sold some magazines, the magazine sold some ads, and everyone had a good laugh. In Mumbai, it’s easy to forget that the vast majority of this country’s 1.2 billion people would look at the skyline with much more jaw-drop awe than a Kentucky runaway would at her first glimpse of the Hollywood sign. Behavior we take for granted can still be shocking to a large section of the Indian film audience.

As a local journo friend of mine wrote to me a few days later, “We don’t like to assume that our ‘stars’ have sex.”

In the piece, I had alluded to the fact that this movie star, “a Top Gun–era Tom Cruise with a better tan,” had been accused in the online gossip columns of inter-floor booty calls with a co-star who lives in the same building. This was all in service of my thesis: to go into the interview with a gossip-composite of the man, lay it down, and through the catharsis of getting to know him, refute, confirm or dispel various facets of this very public figure versus the human being seated across from me on the L of his high-rise living room couch.

Quoth Paragraph 3: “What I really want out of this meeting is to decode the online bollocks dipped in bullshit that have fused into a public persona akin to this: Shahid Kapoor is the most arrogant, difficult, time-wasting, womanizing, talented egomaniac in Bollywood.”

Of course the italics were meant to connote an assumption, not an opinion, but the sentence soon began to appear online as a direct quote from me. Trolls are not known for their appreciation of set-up or subtext.

Detractors are a healthy part of the journalistic cycle, but to be so lambasted so quickly, so baselessly, I confess, it got to me, and at one point after the rot began, mea culpa, I typed into the tweether: “If you’re going to come out from under your bridges into daylight to insult my writing, learn how to fucking spell.”

This may have been ill-advised. My blue notification bubble remained at 20+ through the salad course. A quick call revealed the power was still off back at the office, and as rice and curries were served, our digital editor was visibly giddy. For her, this was all unique visitor traffic to the website.

“Ah. I see,” she said, mulling over what else might have caused so much offence, “you also said he was smoking.”

I had indeed written that Shahid Kapoor was smoking. Because he was smoking. In India, or at least in the land of fundamentalist #shanatics, even this can pass for outrageous.

Then a hate-tweet came from a fan in Russia. It was going global

By the time we’d finished lunch and confirmed there was still no electricity back at work, I’d gone home and opened my laptop to find tweets like this: “You said Shahid Kapoor was smoking.” “No. He doesn’t smoke.” “You are wrong. He doesn’t.” “You are only out to speak negative things against him.”

How do you argue with that? What was even more confounding was an internationally known journalist, author, and acquaintance writing to me on Facebook, with no irony I could detect, saying, “I’m pretty sure Shahid quit smoking a few years ago.”

I’m pretty sure I quit smoking a few years ago, too. But I’m smoking right now, you know what I mean? This was getting weird. Then a hate-tweet came from a fan in Russia. It was going global.

It’s worth noting that the world’s largest film industry includes as part of its audience the world’s largest diaspora community. The annual Indian International Film Awards—the Indian equivalent of the Oscars—aren’t even held in India, but in places like London, Dubai, Amsterdam, Toronto, and, most recently, in Tampa (where our man Shahid shimmied to the hit film song “Lungi Dance” with Kevin Spacey, Keyser Söze himself, who’d wrapped a lungi, the south Indian sarong, over his tuxedo).

Once the U.K. woke up, I was being referred to as “Dave Beastling.” This was about the time I started receiving tweets, Facebook messages, and emails from friends just tuning in, asking what in the name of Hindu Heaven I’d done now.

“I don’t rightly know,” I lied, relieved that at least, so far, no one whose professional opinion I valued had told me to “go home and get my fuckin’ shine box.”

I may not have set out to tilt the Shahid Kapoor story this way, anything but—I thought our hero came out sounding endearingly human, which is all I’ve been trying to do with these celebrity profiles all year—though now that things were in full whirl, another confession: I started to enjoy it. The regularly tweeted rhythm of the attention after so long thinking no one was reading any of my stuff. It felt good. And not long after I admitted that, someone, somewhere, after a full diurnal cycle of focused wrath, turned off a tap. Like the devil Keyser Söze, poof, it was gone.

A minor catharsis. I slept badly.

The next morning at GQ HQ, the strip lighting was full fluorescent overhead, the trolls had retreated back under their bridges, and sitting at my desk, feeling a bit like Mark Zuckerberg at the end of The Social Network, my colleague who’d been in Shahid’s living room during the interview that day, a personal friend of his who can also attest to the smoking, perched herself on the edge of my desk and asked how I was handling everything.

“Does Shahid like the piece?” I asked.

She looked up from her phone mid-text and smiled. “He loves it.”