The memories of starting a new life in Greece, coupled his adoptive country’s seemingly never-ending economic and social crises, form the basis of his project “Shadows in Greece.”

It used to be a country people emigrated from. During the greater part of the 20th century, the Greek diaspora spread and linked up throughout the globe. But the fall of the Soviet Union transformed the flows of people in Europe and beyond. By 2001, Greece had an immigrant population of over 762,000 – about half of which were Albanians. Photographer Enri Canaj and his family were among those who left when communism fell in the small Balkan country. The memories of starting a new life in Greece, coupled his adoptive country’s seemingly never-ending economic and social crises, form the basis of his project “Shadows in Greece.” Some things have changed since his childhood, others have remained the same. But without judgement, he captures the underbelly of a gritty Athens that seems as abandoned as the Olympic Village the country spent billions of dollars on in 2004. He joined R&K from Kukes in Albania.

Roads & Kingdoms: When did you leave Albania for Greece?

Enri Canaj: I left Albania when I was 11 years old. During the early 1990s, Albania’s political system changed. It was total chaos. I left Tirana with my family, but I couldn’t understand why at the time. For me, my country was beautiful and I was just a child. We went to Athens by bus. The journey last more than 15 hours. I remember that my parents sold all our possessions and I felt like I would never return.

R&K: What were your first impressions of Athens?

Canaj: When we got to Athens, I remember the streets being full of life, seeing those big ads and posters, the shops, the bars… It was amazing. The first place we stayed at was a small hotel in the center of the city. That part of town welcomed all the immigrants at the beginning – most of whom were from Albania. So we stayed there the first month, on the third floor of the hotel. Young girls who worked as prostitutes lived on the other floors. They were my first friends in Greece.

R&K: You were immediately confronted by the positive and the negative sides of Greece…

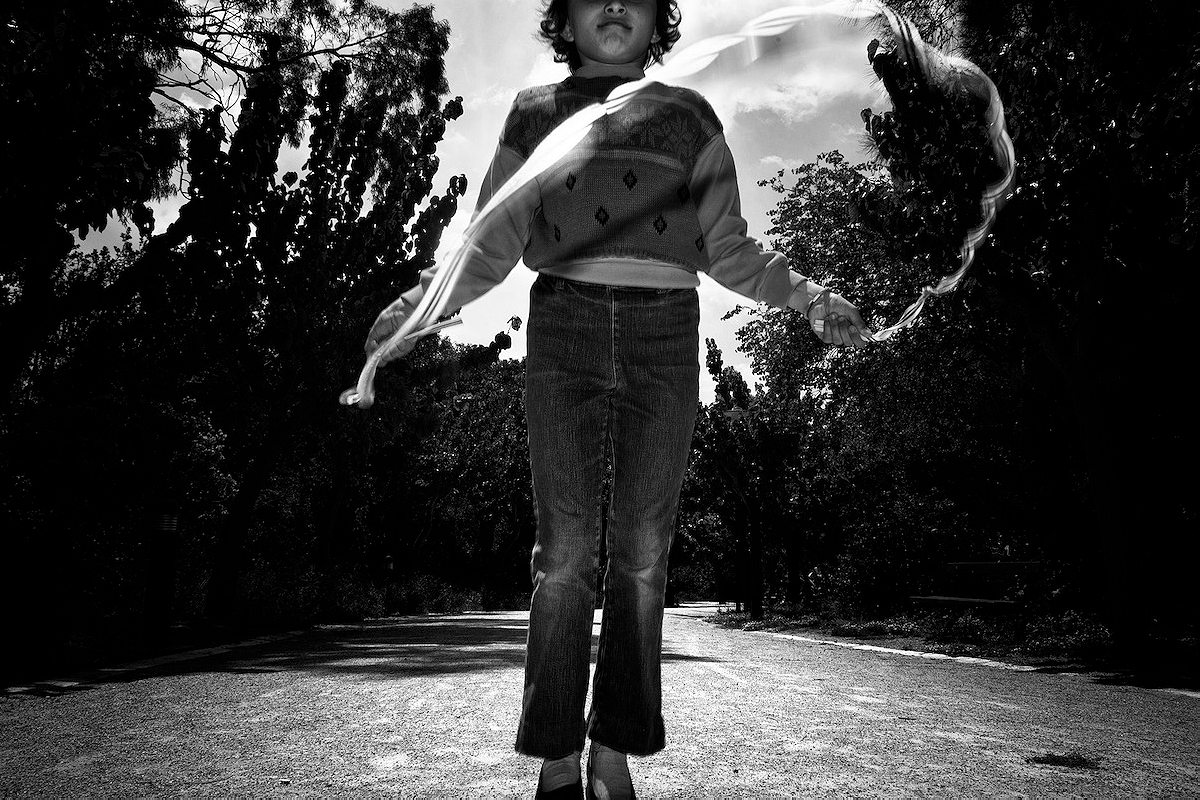

Canaj: I can’t say that the negatives were the poverty and the prostitutes. This was something new, I believe, like the first difficulties that any immigrant goes through. For me, these girls were just beautiful. And I had the energy and curiosity to learn and to see all that was around me.

R&K: They were the ones who taught you Greek?

Canaj: Yes. But after a month we moved to a house with three rooms. We rented one, the others were both occupied by Albanian families. That lasted for the first two years. Greece was something new for us, and we were new for Greece. After the first few years, it became much easier for me to socialize with other communities.

R&K: How do your childhood memories compare to what you saw during this project?

Canaj: In general, it’s hard to move to another county. But I can say that things are much harder now for immigrants in Greece than what I lived through. The number of immigrants is much higher, and because of the economic crisis and social problems in Greece, racism is deeper and more violent than it was. I was very moved to see that, and it influenced my project greatly.

R&K: When did you actually start “Shadows in Greece”?

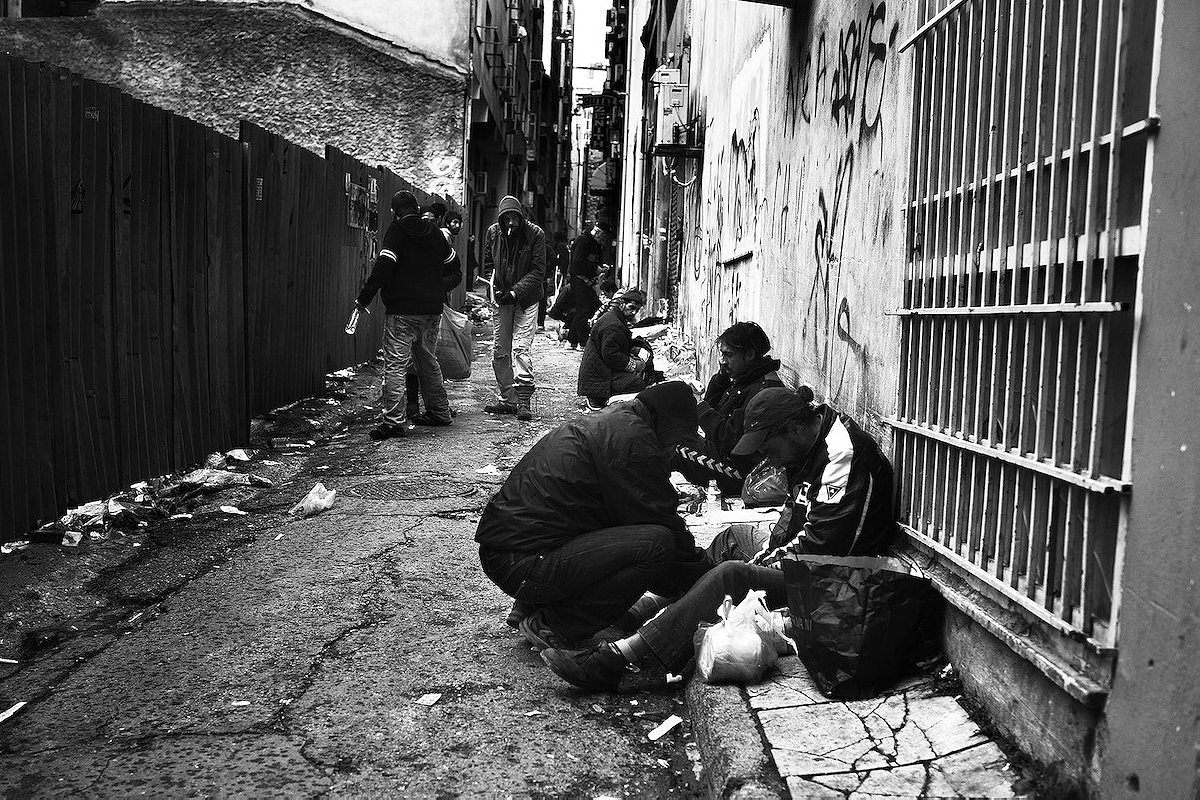

Canaj: I started in 2009, when the crisis started. I wanted to take pictures to show the current situation in the city. The changes were huge. The center quickly became a ghetto. It was very dangerous. It’s still the case today.

R&K: At the time, we saw images of people protesting and rioting in Athens. You chose to photograph something else…

Canaj: The people in my photographs aren’t the ones protesting. For me, the crisis was not only the protests and riots. It was all of what was behind them that was difficult to look at: the fear, the sadness, the hopelessness. For me, that was the real crisis.

R&K: It’s a giant contrast to what happened to Greece during the Olympics.

Canaj: That time was incredible. After so many years, the Olympics were back in Greece. The enthusiasm was high, the economy was great, the city was clean and safe. You could feel the happiness of the people, the new shops, bars, hotels, restaurants… Now, it’s the complete opposite. Not only for the city, but also for its people. The Olympics now feel so far away, like a dream that never happened. Like a joke.

R&K: The subjects of your photographs – what happened to them at that time?

Canaj: They were still in the city, but not in the center, and their living conditions were better. At the time, no one would prostitute themselves for five euros. Of course, there were problems, but it was easier to survive.

R&K: Can you talk a little more about these people in your photographs?

Canaj: I didn’t know them before starting the project. I went to these places in the city center every day for the past four years. That’s how I met them. At the beginning, no one wanted to talk to me. They were scared and suspicious and I was embarrassed. Then I just decided to talk to them and explain what I wanted to do and why I wanted to photograph them. I talked to them as I did with my friends, without prejudice.

R&K: Did you tell them about your personal story with Greece?

Canaj: Yes, I told the ones who were interested. When I shared my history, the connection was stronger. I remember talking with them and just hearing their stories, their problems. I understood that it could make them feel a little bit better. They just wanted to express themselves. So it’s us, as a society, who should not be indifferent – and of course the government shouldn’t either.

R&K: Do you think the Greek government has forgotten them?

Canaj: They are forgotten by all, unfortunately. The government has cut everything, the programs that used to help do not exist anymore. Passers-by see them as parasites, or they are invisible.

R&K: What do you think about when you think of Greece’s future?

Canaj: I am an optimist. In my life, I have always seen things under this lens, so I want to believe in a better future for Greece and its people. The crisis is still present and it has affected all of us, all professions, all life aspects… But I believe that the Greek people are very proud and that this is their weapon to affront difficulties.

You can see more of Enri Canaj’s work here and follow “Shadows in Greece” here.