The story of a working class immigrant family and a changing city.

When I was young my family lived in West Kowloon, a residential area emerging from the industrial past of the peninsula. Our apartment was tiny. Like most flats in the city, our living room was our bedroom and our study. But what set ours apart was that we had converted the balcony into a multi-purpose room—part kitchen, part shower, part laundry, and part storage room. We developed a streamlined operation in the evenings: We boiled water on the stove, poured it into a bucket of cold water for showers, and used leftover water to hand-wash our clothes, all in one place.

We shared a bathroom with our nice neighbor, who made his living as a butcher. It was all the way at the end of the hallway by the stairs. Dad never let me go alone, because there were no security guards in the entire housing complex, and old ladies on our floor had had their gold necklaces yanked from their necks before.

I was 13-years-old and careful not to broadcast my family apartment’s shortcomings to my schoolmates. Our sixth grade geography textbook showed photos of our building and mentioned that the complex was one of the oldest public housing projects and that the government intended to demolish it. Even though my apartment left some things to be desired, I was still proud to show my friends that there was something famous in my little world, “Look! That’s where my family lives!” I excitedly told my classmates.

In the late 90s, the government bulldozed the whole place and the housing project was no longer living history. Most tenants moved into a brand new complex right across the street, and we did too. We were ecstatic to have a real shower, a separate kitchen and a living room. And we didn’t have to sleep in the same bed anymore!

My parents moved our family from the Mainland to Hong Kong so that our family could lead a better life. “This quick turnaround in housing would have never happened back in Guangdong. The Hong Kong government is so efficient and reliable,” Dad said. “This is the place where the poor little guys can make a reasonable living and have a decent life! Now you understand why we worked so hard to immigrate here? Baba wants you two to grow up in a better environment.” Dad said that with a mixed Cantonese and Hakka accent (Hakka is a dialect spoken in Southeast China) the day we moved into our new flat, hugging his children tightly.

My baba (Chinese for Dad) was a patriot, but he loved Hong Kong, too. Although every October 1st he religiously tuned in to watch the celebratory National Day shows put on by the Communist Party in Beijing, and sung songs of praise to the motherland with over-exaggerated vibrato, he never hesitated to point out that “the Brits did something right.” Some of the first instructions he gave me when I first moved to Hong Kong were, “Don’t cut the queue. Don’t litter. Don’t spit. Don’t jaywalk. Don’t speak loudly in public. We are not on the Mainland anymore.”

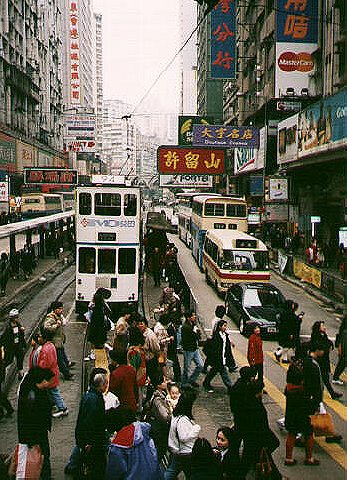

Hong Kong emerged as a world-renowned financial center and tourist destination after 150 years of British rule. It has more skyscrapers, a higher population density, and more expensive housing prices than New York City. But it also boasts of parks, woodlands, reservoirs, and scenic rural areas that cover two-thirds of the archipelago. It was a crown colony of the British Empire and the pearl of the east for the Chinese.

But Baba didn’t move to Hong Kong because it was equal parts Manhattan and Hawaii. Like most immigrants, he joined the corps of city mice because he heard there were good jobs, his children would get a better education, and he likely wouldn’t have to bribe the doctor when his children got sick.

My father is a man of ordinary stature and extraordinary pace—he is the fastest walker and quickest eater I’ve ever known. He has a full head of dark hair and a young complexion. Dad has a quirky but endearing sense of humor, and is always dependable and considerate when I ask him for advice.

I don’t think “independent judiciary” or “open press” were explicit criteria of Baba’s decision-making process, but he had a hunch that a culture of transparency and accountability would make life easier for the poor. Hong Kong felt more secure overall, partly because standards mattered. We could generally trust the government to deliver public services, and trust the quality of products and services we purchased and consumed. Unlike my cousins on the Mainland, who from a young age developed the street smarts of avoiding soy sauce made from industrial wastewater or watermelons injected with red liquid, we lived our daily lives with a lot less suspicion and a great deal more idealism. Baba was particularly grateful that we could take information and announcements from the government at face value—and it’s wonderful to have confidence in something, instead of constantly deciphering and second-guessing the subtexts.

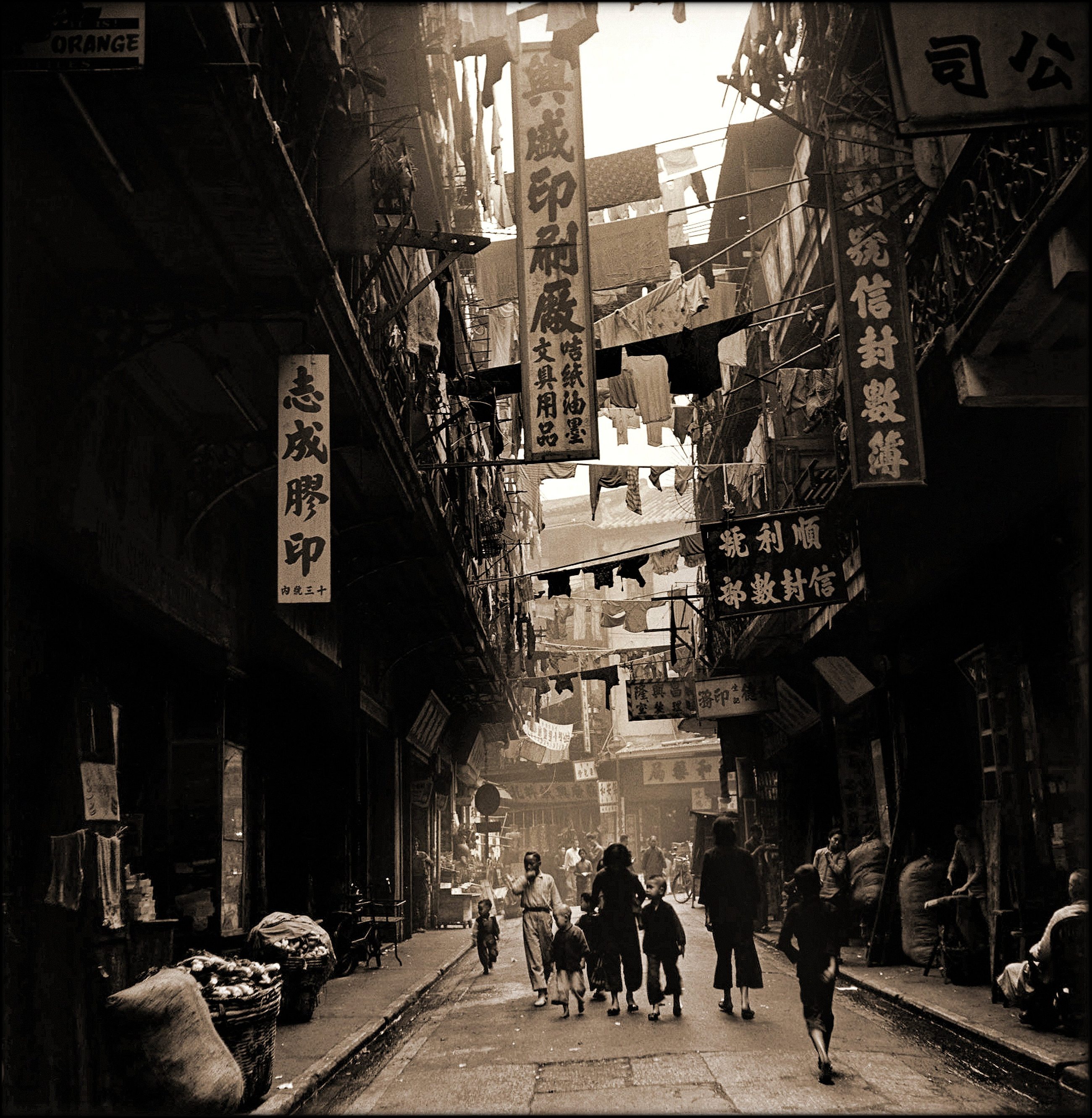

Baba was born in a Hakka village, a walled multi-family communal living structure, in 1952. He was the youngest of three children from a somewhat well-to-do family. His mama, my grandma, was cheaply bought as a maid before her tenth birthday. She grew up doing all kinds of house chores, taking care of her future husband and his younger siblings. After she and my grandpa were married, she continued to care for the house and their children. But my grandpa, whose musical talents I am supposed to have inherited, was preoccupied with playing the erhu—a two-stringed bowed instrument often called the “Chinese violin”—and running a local opera troupe. Most of my baba’s memory of his baba came from watching opera performances from the VIP seats backstage, on top of the bamboo poles that were used to construct the stage. That must have been where he got his over-exaggerated vibrato.

My uncle was sold to a rich family

Somehow my dad developed a trait that he certainly didn’t receive from his father—an extraordinary attention to the details of his children’s lives. He remembered the names of all my teachers and friends, and those of my favorite TV shows, authors, and singers. He would come home with a new tube of toothpaste on the exact day we ran out.

It was almost like a DNA mutation—Grandpa was nothing like that to his children. He squandered away his family’s modest wealth and passed away before my baba turned seven, leaving my grandma with three children and no financial means. My uncle was sold to a rich family a few miles away for the price of salt and vinegar, but he ran away and came back to my grandma, who cried many, many rivers. My aunt moved to Hong Kong along with relatives who “didn’t want to starve to death in the village,” as my dad once described it, but didn’t speak to my grandma again until 10 years later, because she was so ashamed that her meager income went to support her children instead of her mother.

Baba attended middle school for free because the headmaster hated to see wasted potential, but he suffered many sleepless nights in the bitter cold winters. His friend shared a bed with my dad at no charge; but when the friend rolled over with the entire blanket, Baba did not feel he could demand more generosity. That must be why his first order of business in the winter was to make sure we had enough blankets.

Financial hardship, frugality, and an astonishing tolerance for discomfort marked the lives of people from Baba’s generation. But even in those trying times, my dad developed a reputation among friends and family as a “super-saver” with “superhuman resilience.” He worked three part-time jobs in three different textile factories before he got a more permanent position with a public transport bus company. He worked night shifts for more than sixteen years, directing fleets of buses to the right depots and cleaning the city’s trademark double-deckers, until he retired at age 60 in 2012.

For years I wondered if there was a limit to the stamina of this small man—Baba shopped and cooked, and delivered lunch boxes to my school every day, even when he was supposed to be sleeping during the day. He would walk a few extra blocks at the end of his night shift to get me a pineapple bun for breakfast every morning, because it was fifty cents cheaper at that particular bakery. He smuggled some scrap paper and pens for me to do homework, just to save a few dollars here and there. Sometimes I thought he was too stubborn and unnecessarily stingy (especially when he didn’t account for the opportunity cost of time and effort)—but where would I be without that military discipline of his? Or more precisely, the perseverance fueled by the unwavering hope and belief that his sacrifice would set me up for a better future?

The face of Hong Kong is usually one of a successful financier or that of a happy tourist. But I think of the army of humble and hardworking blue-collar workers who labor behind the scenes to provide the quality services a powerhouse world-class city enjoys. Most of them do not speak much English beyond “Hello,” “F(Th)ank you,” and “L(n)o problem.” In fact, they often speak Cantonese with a thick dialect accent, be it Hakka or others.

Many Hong Kongers were apprehensive but ultimately relieved when Margaret Thatcher and Deng Xiaoping announced the “One Country, Two Systems” deal in the 80s, because they all left the Mainland for a different future and a new hope. They wanted to raise their family in a city with a reliable supply of clean water, cops who protected the people, and roads where a majority of the drivers followed the traffic rules. They prioritized their children’s education, because hard work and academic achievement were tickets to social mobility in Hong Kong. You did not have to come from a middle or upper-middle class family to have a successful career and a stable life. Baba made the right bet, too—I thrived in the meritocratic culture, and somehow I even made it to an elite college in the U.S., for free.

My parents did not have the resources to be “tiger parents” even if they wanted to. I took subsidized pipa lessons offered at our public schools (I followed my grandpa’s footsteps and learned to play a stringed Chinese musical instrument), but by and large we did not have the money to go through a regimen of serious music, dance, or sports lessons. But with access to books of a robust library system and the freedom to debate policies without fear of reprisal, I started developing what educators call “critical thinking.” I learned what leadership and humble service looked like while checking the blood pressure of the elderly and leading field trips for young children, alongside the staff of Red Cross and other well-established NGOs. Baba was proud of how I was growing, and pleased that it came at a relatively low cost. It was easier for hard work to pay off, or it seemed like odds might be in our favor, when a system was designed to provide opportunities to the underprivileged.

Then something changed while I was in boarding school and college overseas, far away from home. I still can’t quite comprehend how it all happened, but my close-fisted Baba accidentally and secretly became a proxy for a former colleague’s gambling addiction, at the expense of his family’s welfare. He lost his entire pension when he agreed to be the guarantor for this former coworker’s debt, because Baba “felt bad for him.” His marriage with Mama was falling apart too, because she had trouble believing in his lies.

I cried myself to sleep in my dorm room on the nights we chatted on the phone. My conversations with friends back home also felt increasingly downbeat: Lawyers were concerned about the independence of the court system; teachers were frustrated about the introduction of “Patriotic Education,” which would erase the “Tiananmen Square Incident” from history. Yes, the Hong Kong economy has also benefited from China’s legendary, uninterrupted, and unprecedented growth—but somehow almost everybody felt bleak about the future; nobody was satisfied with GDPism. The changes and uncertainty didn’t feel comfortable at all—were we trading our autonomy for prosperity? Are we exchanging the “free speech that has freed us” for favors from the central government? Can we rely on this committee of tycoons and plutocrats to elect the leader to govern a city where the income gap is one of the widest in the world and where one-fifth of the population lives in poverty? And Baba, why did you choose your coworker over us? Tell me, please tell me the truth—what is happening, and whose story can we trust?

I wish I could join the protestors

Baba once told me he has had a thousand heartbreaks, but the worst one is the guilt he feels about disappointing his children, and how that strained our relationships. As I got older, I began to appreciate the depth and height of his resilience when I caught glimpses of how he copes with the pain of bitter regrets, losses, and failures.

“How are you, Baba?” I asked during one of our phone calls.

“Well, you know, same old, same old,” he replied. “My back pain is excruciating and I don’t know how to pay for everything. But I gotta keep on keeping on. How are you? Is it getting cold over there? Do you have enough blankets?”

All of a sudden I realized that despite the mistakes and setbacks, Baba has kept on keeping on his whole life, and my life is different than it might have been because of it. When I went to bed that night, a new kind of gratitude and courage welled up in my heart—the opportunities in my life are the fruits of my father’s labor, in a special city that offered prospects to immigrants like us.

Unlike Baba, this year on October 1st, I didn’t watch the National Day celebration or sing “March of the Volunteers,” the Chinese national anthem. Instead, I joined in singing “Do You Hear the People Sing?” as I watched the Umbrella Movement unfold on my computer screen. Just as the students sang the song to awaken a revolution in the musical Les Miserables, Hong Kong protestors bellowed the adapted Cantonese version as the anthem for their own movement. My job currently keeps me in the States, but sometimes I wish I could join the protestors myself, to be with them as they brave tear gas and sort recycled trash all night long, because I, too, cherish the hope of a different future that Hong Kong once held for my baba.

Fighting the Communist Party of the People’s Republic of China for genuine democracy, the rule of law, and civil liberties might feel like a losing battle, much like fighting the demons of past regrets and the deterioration of your body. But Hong Kongers will do what they do best: keep calm, and keep on keeping on.

[Header image: “Dusty Hong Kong” by Luke Ma, used under CC BY 2.0]