FC Alga Bishkek was once one of the best teams in Soviet Central Asia. But in the post-Soviet age, the club—much like Kyrgyzstan itself—is mired in the nostalgia of better times.

It is the semi-final of an amateur indoor soccer tournament in Kyrgyzstan’s capital, Bishkek. A team representing the Russian Embassy are playing a team representing a local mobile phone operator, and a diminutive pensioner with a white puff of hair is controlling the game effortlessly.

The embassy team is winning the match 2-0. The white puff of hair strolls around the pitch, five feet four inches tall and 63 years old, directing a troupe of enthusiastic lumberers roughly half his age with barked commands and crisp, unfailing passes. Younger fans in the 100-strong crowd, saturated by televized and online coverage of the English, Russian and Spanish leagues, have no idea who the old man is. They can only murmur in collective deference as he receives an awkward ball at waist height, swivels expertly and traps it dead beneath his foot before spraying it onward with enviable ease.

A thick-set middle-aged fan sitting behind the kids has seen it all before.

“Vladimir Oreshin,” he whispers reverently. “He is better than Pirlo, isn’t he?”

Although that comparison might be a stretch, Vladimir Maximovich Oreshin shook the world in his prime. Or at least, he shook a little-known corner of it.

A NOSTALGIA CLUB IN A COUNTRY SOAKED IN NOSTALGIA

Bishkek’s oldest soccer club, FC Alga, is a nostalgia club in a country soaked in nostalgia. A 2013 Gallup poll of former Soviet countries showed only rueful Armenia regretted the collapse of the Union more than Kyrgyzstan, a small, indebted, landlocked republic unfurled awkwardly across some of Central Asia’s most magnificent mountain ranges.

That sense of loss is understandable. The Kyrgyz SSR was perhaps the republic least prepared for the kind of independence dumped on it back in December 1991. Heavily subsidized by Moscow, the Union’s disintegration was nothing to be celebrated. Pensions and incomes got halved, quartered and quartered again in the space of months as hyperinflation ran wild. Heart attacks hit neighborhoods in waves, as healthy people caved under the sheer shock brought on by an epic collapse.

Communism had not been without its challenges. Political repressions were many and the command economy reduced the nomadic Kyrgyz people’s wandering lifestyle to a series of quotas for meat production. Yet being part of a multinational empire also had advantages. Chingiz Aitmatov, a local writer endorsed by the Kremlin, was read across the Soviet bloc and beyond. Kyrgyz soldiers were part of the celebrated Panfilov division that defended Moscow from the Nazi onslaught. When Yuri Gagarin returned from his historic mission into the cosmos, he recuperated on the shores of Kyrgyzstan’s ethereal Lake Issyk-Kul.

So while the Kyrgyz stake in the colossal, fateful Soviet narrative was small, there was still enough to be proud of. The soccer was much better back then, too.

In Kyrgyz, “alga” translates as “forward,” but for soccer aficionados of Shulgin’s generation the word is a conveyor to a fondly remembered past.

“I can’t tell you who scored how many goals in what year,” says Shulgin. “But I can tell you about the atmosphere surrounding FC Alga, the atmosphere of that time.”

That time. A time when FC Alga held its own in the Soviet Union’s First League, the second most prestigious all-Union division after the Supreme League. A time when crowds of over 20,000 crunched through turnstiles and packed into the country’s main stadium to watch their gods do battle with other gods from teams representing cities all over the Union.

Bishkek, then called Frunze, was as close to a backwater as a republican administrative center could possibly be. The only time and place it ever saw a traffic jam was outside Alga’s home on match day.

Alga never made it to the Supreme League, regularly dominated by the likes of Ukraine’s Dynamo Kiev, the Moscow teams, and Georgia’s Dynamo Tbilisi. Other teams from Central Asia tasted this promised land, but the closest Alga ever got was in 1967, when a swashbuckling, physical side led the First League for what seemed like an age, only to end up two points short of promotion. To hear Kyrgyzstani soccer fans of that era talk, one would think FC Alga in 1967 were Brazil in 1970: an irrepressible combination of skill and bravery.

With seniority in years comes a license to embellish, acknowledges Shulgin. But he chooses a different sort of memory to define the spirit of the age.

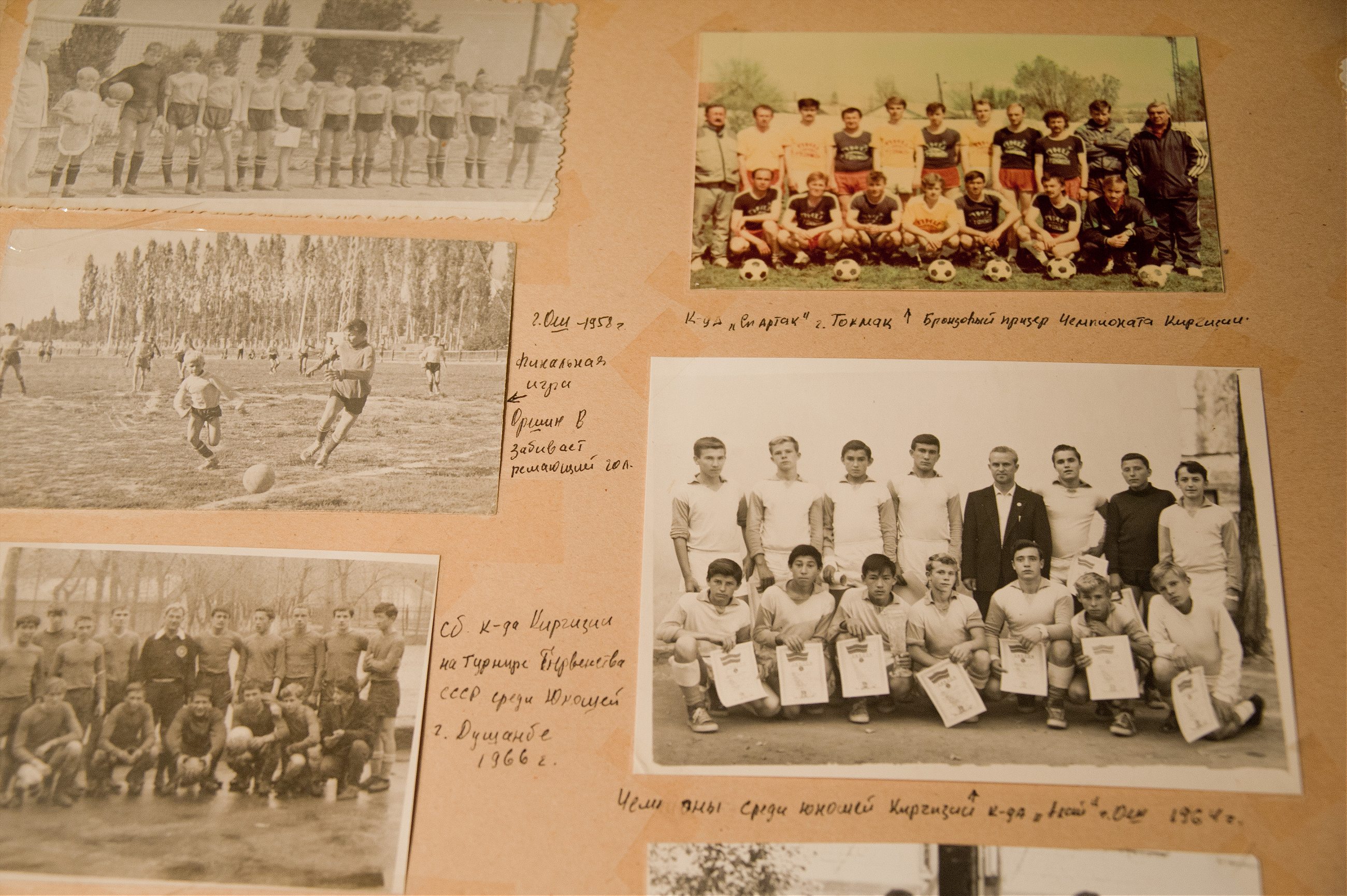

In the 1978-1979 season, Alga were in the throes of a terminal decline, their time in all-Union level soccer coming to an end. A visiting team from Russia—Shulgin is hazy on names—are turning them over, 4-0. Even the side’s most gifted technicians, men like Vladmir Oreshin, Mars Chokmorov and his brother Almaz Chokmorov, are treading water, and there would be no stirring comeback on this occasion.

At one point during an excruciatingly long and comfortable period of possession for the Russian side, a Kyrgyz mother sporting a bright red headscarf and giant lungs rises up to rally the hushed crowd: “ALGA WILL NEVER BE DEFEATED!!!”

VLADIMIR ORESHIN MAY BE ETHNICALLY RUSSIAN, BUT HE REMAINS VERY MUCH A SON OF KYRGYZSTAN.

Vladimir Oreshin may be ethnically Russian, and he may represent the Russian Embassy in meaningless friendly tournaments, but he remains very much a son of Kyrgyzstan. His birthplace, the southern city of Osh, is a very different kind of place to Bishkek, which bears all the hallmarks of a Soviet pop-up city. At the turn of the millennium, Kyrgyz politicians conveniently decided Osh was 3,000 years old and held festivities to celebrate the fact. It is a place dominated by a giant, UNESCO-listed rock called Suleiman, tea-houses that smell of smoking mutton, and dense, winding neighborhoods, or mahallas. On the eve of independence in 1990, Osh was devastated by ethnic violence that erupted as groups of titular Kyrgyz and minority Uzbeks clashed over land and status. In June 2010, events repeated themselves, only this time there was no Red Army to intervene, possibly more weapons, and probably more lives lost. An independent report into the 2010 violence put the death count at over 400. No reliable data for the 1990 violence has ever been produced.

Oreshin left Osh for Frunze and Alga in 1967, aged 15, and soon became the symbol of a small-town club vying for its seat at the Soviet table.

“I suppose they were like our Xavi and Iniesta,” muses Kozhanov, referring to Spain and Barcelona’s phenomenal midfield tandem. “We had some good, strong, center forwards at the time—they could bully the ball into the net—but they weren’t technical guys at all. Oreshin and Chokmorov could plant the ball at their feet so all they had to do was shoot.”

Sitting next to Kozhanov inside the recently renovated Kyrgyz Football Federation, Oreshin demurs. He was no Pirlo, Xavi or Iniesta and certainly not as good as the brilliant Mars Chokmorov, currently confined to his home with high blood pressure. He was just a hard-working boy from Osh with “two hearts”.

“One heart upstairs and one heart downstairs,” Kozhanov grins.

FOR EVERY FAMOUS VICTORY THERE WAS A TOTALLY AVOIDABLE DEFEAT.

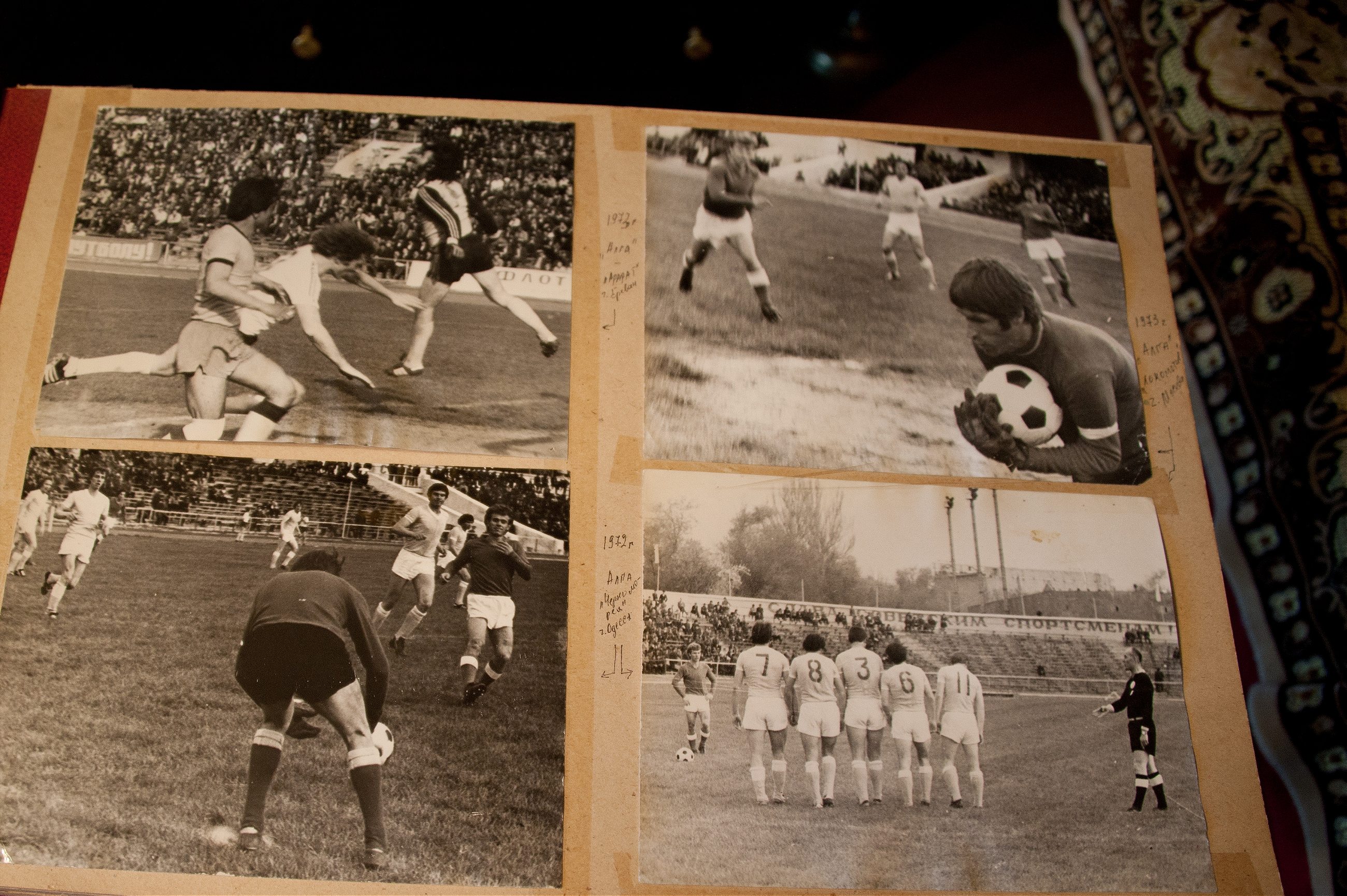

Oreshin’s Alga were certainly not Brazil of 1970. For every famous victory there was a totally avoidable defeat. Alga were a thorn in the side of FC Kairat, the strongest club in the neighboring Kazakh SSR, but more often than not lost to FC Pakhtakor, the Uzbek SSR’s “Cotton Pickers”, who tended to go straight back up whenever relegated from the Supreme League.

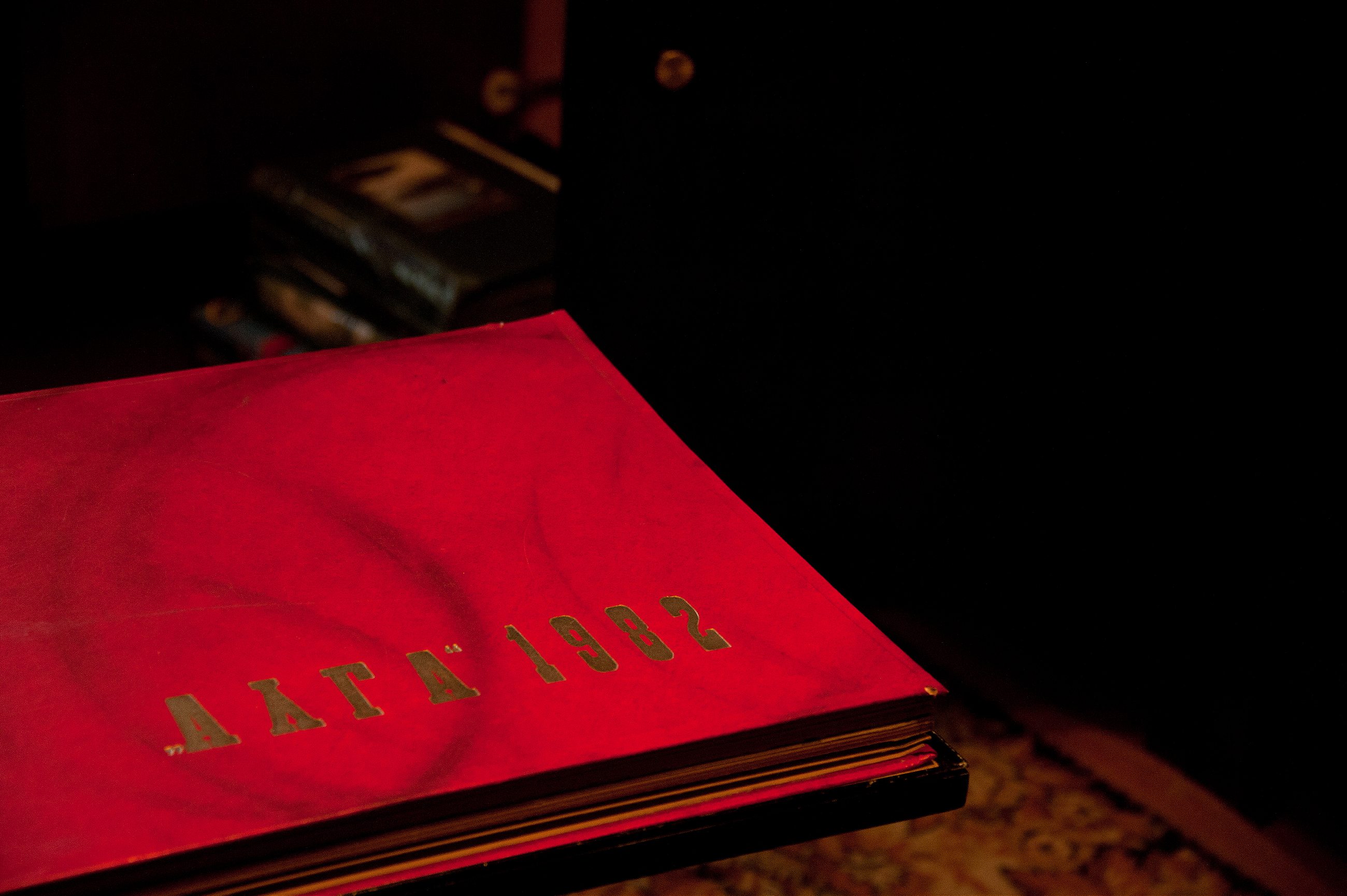

Of all FC Alga’s greatest moments, however, many of them frozen as black and white stills in a gloriously nostalgic scrapbook presented to Oreshin by the Kyrgyz government upon retirement, there is one enshrined as legend.

Dynamo Moscow, one of the strongest sides in the Supreme League, were tied with Alga in the Soviet Cup. Their players thought they would win the game in their sleep.

“They had guys like Bubnov, Gazzaev, all of them in the Soviet Union team. People were watching the game from trees outside the ground,” says Oreshin. “But in the end, they couldn’t get the ball off us. We won 3-0. Gazzaev was swearing like a dog. He didn’t even turn up to the press conference after the game. People still stop me in the street and talk about that game. How did we do it?”

FC Alga may ultimately have been held together by one man, but for much of its existence the club was placed on the balance books of a behemoth metallurgical plant that employed around 10,000 people producing machinery for collectivized agriculture.

Although being paid for playing soccer is not a concept in harmony with the dictatorship of the proletariat, in reality every Soviet soccer player in the top two divisions received a wage. Kozhanov, Oreshin, Chokmorov and their teammates were placed on the factory’s payroll as “sports instructors” earning 160 rubles per month, but they never instructed any sport and their relationship to the factory as a whole was nominal.

ORDINARY WORKERS HAD TO WAIT TEN YEARS ON A LIST FOR A CAR, BUT EVERY ALGA STAR HAD ONE

Other benefits accrued on top of the players’ basic wage, including bonuses for wins and individual performances. Ordinary workers had to wait ten years on a list for a car, but every Alga star had one. The differences between communist soccer players and the people watching them were not as pronounced as they are in many countries in the 21st century, but were visible nonetheless.

One morning in 1972, towards the end of a lackluster training session, the club’s coach at the time, a short, irascible Armenian called Artem Falyan, decided his players needed to be reminded who they were working for, and took them on an impromptu visit to the plant. Some of the players were nervous, fearing the workers might view them as “nakhlebniki”—parasites—and waited in the courtyard in silence as the factory director called his staff out to meet them.

What followed was less a Soviet set piece and more an unstoppable outpouring of affection as the people of the factory proved their fears groundless. They thundered into the courtyard and mobbed them with handshakes, backslaps and kisses. Some even offered their lunch.

“ALGA! ALGA! ALGA! ALGA!” they chanted.

Vladimir Oreshin, a local god, stood among the thronging masses, fresh from welding and working the lathe, their faces grubby, their hands swollen from exertion, and felt tears in his eyes. “People were different then,” he says.

Kyrgyz parents tend to think twice before they call their child Manas. It is a name so strong it can leave the named feeling like they are walking in a shadow. It is the name of Kyrgyzstan’s epic hero, a figure of ancient folklore revived with a vengeance by the country’s first president, Askar Akayev, whose life story is sung by elderly bards at village festivals and clan get-togethers. Manas, it is said, kept the imperial Chinese armies at bay, pegged back the Uyghur hordes and united the disparate Kyrgyz tribes into a single nation at a time no-one can attach a date to. Nothing any mortal can do would compare.

Coaching the modern incarnation of FC Alga, restored in 2010 after a 16-year absence, must be like being called Manas.

Veterans, including Kozhanov and Oreshin, attend games from time to time, sitting in a specially allocated part of the near empty stadium that used to be full, talking about the old days.

Perhaps they reminisce about the time Alga visited Nepal as part of a low-level diplomatic delegation from the Kyrgyz SSR and everyone had to wait for an hour at half time as the Nepalese King took lunch. Or maybe they discuss the time the Moroccan national team came to Bishkek and played Alga in a friendly. Alga were winning 5-0, and a Soviet official raced onto the pitch to tell them to stop scoring goals and allow the Moroccans to save face. When Mali arrived, it was the same scenario. Back then, Kozhanov observes, the Africans couldn’t really play soccer at all, but ever since their game has progressed immeasurably while Kyrgyzstan’s has hurtled backwards. Now many of the best players in the largely symbolic eight-team Kyrgyz league are African. The modern day Alga cannot afford their wages.

The territory surrounding Alga’s temporary training ground on the outskirts of the city is overrun. Weeds, including flowering cannabis, streak across the landscape like a green rash. Standing before the rusty iron gates of the disused stadium is the ubiquitous Lenin. Few locals treasure or romanticize him—he is not really theirs after all—but there is little impetus to deliberately discard him as was the case in other republics. Historically, the Kyrgyz had always been on the run from someone. It was the state Lenin created that provided them with their permanent home.

The man that coaches Alga, Nurzad Kadyrbekov, is humble and unassuming. By all accounts, he is doing a fantastic job. Against expectations, Alga are topping the Kyrgyz league by four points going into the last third of the season, admittedly with their better-resourced rivals having played two fewer games. Mindful of the location’s grim aesthetic, Kadyrbekov is at pains to convey the fact that FC Alga usually train somewhere better. His players are only training here today because their principle training ground is unavailable, he says.

His job is difficult. In addition to struggling under the weight of other people’s memories and getting the best out of limited players, he has to persuade the fiscally-challenged Bishkek municipal government that now finances Alga of the need to improve the squad and raise salaries in order to prevent players departing to the privately-owned clubs and teams in oil-rich Kazakhstan. Although Kadyrbekov did not want to discuss figures, a contact in the Mayor’s office doubts the Alga players can earn much more than $200 per month, the standard salary for a frontline employee of the state. The municipal government has cratered roads to repair, houses to connect to the energy grid, and a chronic shortage of kindergartens in Bishkek. Alga players may not be in line for a pay rise for some time.

Almost any retired soccer player is left with what ifs. They are the unanswered questions, shortcomings and near misses that in addition to the triumphs provide a career with its shape. Roberto Baggio won a Ballon d’or, two Italian league titles, a Coppa Italia and the UEFA cup, but is mostly remembered for the skied penalty kick that cost Italy the World Cup in 1994. Michael Ballack, every inch a winner, had a legendary record for losing finals. Paul Gascoigne, a darling of Italia ’90 whose career was blighted by alcoholism, famously turned down a move to Manchester United, a decision manager Alex Ferguson admitted “hurt them both.”

Vladimir Oreshin, who made the USSR youth squad but was never considered for the senior version, had plenty of offers to leave Alga and join teams playing in the Supreme League. But the difference between an offer to play for someone else and the opportunity to do so weighed around 160 kilograms and chaired the Kyrgyz SSR’s Council of Ministers for a decade from 1968 to 1978. He was Akhmatbek Suutubaevich Suyumbaev, Alga’s most dedicated and politically important supporter.

In 1973, the young Oreshin, then 21, was tempted by the trainer of FC Chernomorets, a club based in Odessa, Ukraine. The team’s coach had met him when the clubs played each other the season prior and had placed the keys to a three room apartment in Odessa and a car in Oreshin’s hand, actions that in the modern era would be understood as “tapping up” another club’s player. The 1973-74 season turned out to be one of the best in FC Chernomerets’ history, as the club went on to finish third in the Supreme League. But Oreshin would not be a part of their success. As he was sitting on a plane to the Black Sea coast via Moscow, counting the seconds before takeoff, a black Volga pulled up on the runway. Four huge men in black suits, unmistakably KGB, bailed out of the car and ran up the gangway to board the plane.

“Are you Oreshin?”

“Yes, I am Oreshin.”

“You have to get off the plane.”

Oreshin was quickly transported from the airport to the expansive room of the Council of Ministers where he was left alone with Suyumbaev. It was an interrogation.

“Where were you born, son?” Suyumbaev asked.

“Osh, Kyrgyz SSR, Akhmatbek Suutubaevich!”

“Then why do you want to play your football in Odessa? You have a flat here. The people love you. You need a car? You can have three cars…”

“I don’t need anything, Akhmatbek Suutubaevich! Just please don’t kill me!”

Suyumbaev believed that the ransacking of Alga’s promising 1967 side was a crime that had denied the republic the opportunity to shine on the biggest stage of all, and he was damned if he was going to let it happen again on his watch. Oreshin, who ungrudgingly refers to Suyumbaev as the “father of Kyrgyz football,” returned to the squad and remained with Alga even after they were relegated to the Kyrgyz SSR’s local league, eventually retiring from professional soccer aged 47.

For all the adulation they received, Alga’s gods never forgot there was a god still greater.

The new patrons of Kyrgyz soccer in the capitalist era, Suyumbaev’s heirs, are businessmen Askar Salymbekov and Sovetbek Sakebaev.

In addition to being two of the republic’s most successful entrepreneurs, both Salymbekov and Sakebaev were MPs in the Ak-Jol party that supported Kyrgyzstan’s second president, Kurmanbek Bakiyev. Currently, both Salymbekov and Sakebaev have brothers that are MPs in the Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan, loyal to Kyrgyzstan’s fourth president, Almazbek Atambayev, which helped overthrow Bakiyev and effectively dissolve Ak-Jol in a bloody revolution on April 7, 2010. If you are a wealthy businessman in a country that combines political pluralism and endemic corruption, flexibility is a must.

It is Salymbekov’s club, FC Dordoi, that has claimed eight out of the last ten Kyrgyz league titles and play in obscure tournaments with the champions of Myanmar and other countries too lowly ranked to compete in the Asian Champions League. Dordoi, too, is the club with the African players. No one really knows how they arrived in Bishkek, but Daniel Tagoe and David Tette, both born and raised in Ghana, are rumored to earn up to $3,000 dollars a month, and now also turf out for Kyrgyzstan’s national side, ranked 146th in the world.

FC Dordoi takes its name from Salymbekov’s Dordoi bazaar in Bishkek, the largest bazaar in Central Asia, whose turnover was around twice Kyrgyzstan’s GDP at the peak of its powers in 2008. Sakebaev’s FC Abdysh-Ata, based in the provincial town of Kant, have been Dordoi’s closest competitor in recent years, but as a team financed by a brewery, can only get so close.

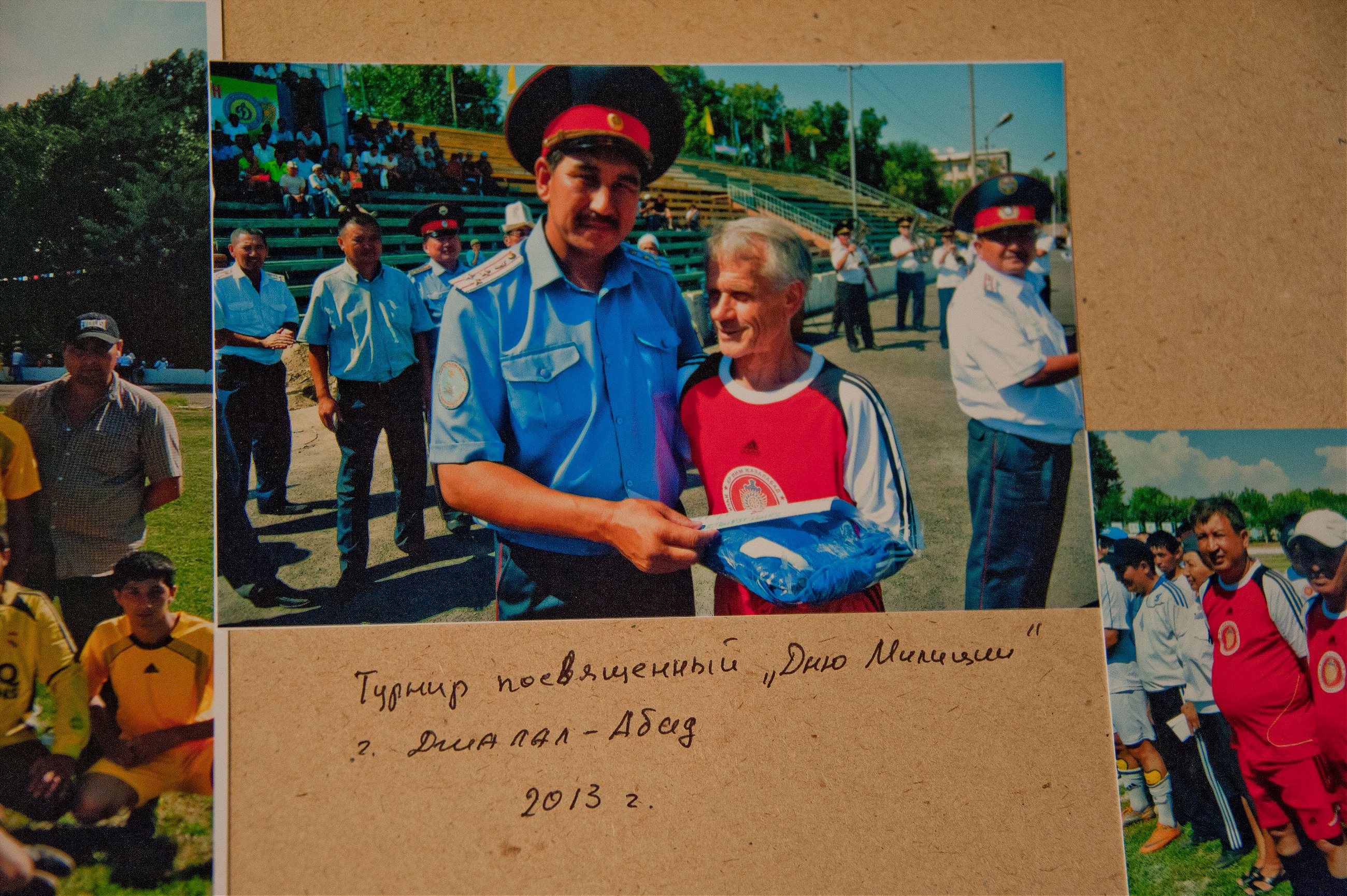

Nevertheless, Sakebaev plays his part in developing Kyrgyz soccer, funding several youth and women’s teams that wear the company logo splashed across their strips, while FC Abdysh-Ata’s stadium is the most modern and well kept in Kyrgyzstan. When Oreshin plays there in veterans’ tournaments, Sakebaev is always sure to ply him and his friends with free beer.

Kyrgyzstan may miss the size and significance of the Soviet Union but it has already shed much of its Soviet skin. The generation belonging to Oreshin and Kozhanov—for whom life was partly planned, nationality mostly meaningless, and who loved nothing more than the game, the people and the post-match sauna—appears more and more like a Leninist anachronism. Nowadays, Kyrgyzstanis are oligarchs, bazaar traders, nationalists, liberals, religious conservatives and feminists, but seldom communists.

Where once they told witty anecdotes, Bishkek’s politicized taxi driver class now talks darkly of “external projects”, whose success or failure will determine the country’s destiny. The Chinese are arriving, building roads, then settling down and marrying Kyrgyz women, they complain. Russia, which never really regarded Kyrgyzstan as a sovereign state, has decided it wants an empire again. Islamists aim to turn Central Asia into a caliphate and everything, without exception, is America’s fault.

Things will never be the way they used to be, because they never are, and every year of independence only adds to the uncertainty. Kyrgyzstan’s future might be brighter than, bleaker than or broadly similar to its frustrating present. But for those with better times to remember—times like the pomp of FC Alga—there is more joy to be had looking backwards than forwards.