Lola Akinmade Åkerström went north—far north—to where the “blue hole” where solar explosions morph into a dancing line of green, red and fuchsia light—in search of the real meaning of the Aurora Borealis.

The narrow beam from Peter Rosén’s headlamp illuminates the viewfinder on my camera, which is balanced atop a sturdier tripod I’d loaned from him. I thought my own tripod would be stable enough, but it seemed flimsy that night as it dug into calf-deep snow. He is pressing buttons with thinly gloved fingers, showing me controls, making sure I have the right settings, or rather, the perfect settings for capturing the only other source of light around us: the Northern lights. Green bands like folding curtains shimmer in the sky above and all around us. Peter’s own camera is already wirelessly at work, capturing a time-lapse of the gyrating Northern Lights.

A staple on many travelers’ bucket list, the Aurora Borealis is a fickle apparition. It occurs when solar explosions cause particles from the sun to collide with gases in the Earth’s atmosphere to create vibrant red, green, and sometimes fuchsia bands of light. And while NASA dutifully monitors these solar patterns, there is still no guarantee you’ll catch a glimpse of the resulting Northern Lights. Even throwing in ideal weather conditions for auroral activity—crispy cold, clear, cloudless skies with little to no moonlight–promises you nothing.

Aurora photographers like Peter, who moved to Abisko 14 years ago and has been photographing the lights ever since, follow NASA’s monitoring website like scripture. They know the strongest auroras appear 24 to 48 hours after a solar explosion. Their gearboxes are always packed and ready with two to three tripods and cameras, several wide angle lenses diligently cleaned each night to remove frost and dust, and enough battery life to beat the threatening cold. They’ve captured thousands of images of these lights, and yet Peter is still out here in a borderline reverent state, making sure my settings are absolutely correct because those lights deserve nothing short of perfection. Then he turns back to the sky, just watching the show, his own camera forgotten in the background.

Just watching the show: it turns out that’s actually the best way to get in tune with the appearance of the aurora. Even though Peter knew about the solar explosions and the possibility of the lights showing up sometime tonight based on NASA predictions, we knew to be outside at exactly 9pm scanning the sky because Anders Kärrstedt, an elder with the indigenous Sámi people, had said so.

Anders had stepped out into that dark February night and had begun scanning the horizon for signs of the aurora a little while earlier. He manages the Nutti Sámi Siida lodge here, along with Nils Nutti and other members of the Nutti family, who open up their indigenous culture to travelers to experience elements of local Sámi lifestyle—from corralling reindeer at their lodge, to cooking souvas (smoked reindeer meat) over open flames, sledding through winter landscapes using reindeer sleds, and scanning for Aurora Borealis while sitting out in a Nordic tentipi.

Anders had been studying the shapes of the clouds, the direction of the wind. Very little activity. A mild green line here and there.

He looked down at his watch. Based on what he was seeing, the lights should appear by 9pm, he told me. He was right: the lights began to appear a few minutes past 9pm and then they burst through the sky with vibrant greens, purples, and pinks, canvassing the entire sky.

We grabbed our cameras and tripods and trotted out into the darkness, hoping the lights would dance long enough for us to set up our gear.

Anders attributes it all to luck–unpredictable luck. “From experience, you know approximately when to expect Northern Lights,” he says. “It’s more like you get a feeling for when it might occur, but many times, you are not even close.”

Regardless of the solar weather, the nearby town of Abisko is scientifically proven to be the most ideal viewing spot in all of Sweden because of its unique microclimate. Abisko National Park is home to the 70km (43mi) long Lake Torneträsk, which helps create the “blue hole of Abisko”—a patch of sky that remains clear regardless of the surrounding weather patterns. So the next night, 48 hours after a solar explosion, when the strongest auroras were coming, Anders’ partner Nils Nutti drove me over the snow and ice-coated Arctic tundra to Abisko.

The Sámi are an indigenous people of roughly 70,000 living in regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola peninsula collectively known as the Sápmi region. Approximately 20,000 of them live in Swedish Lapland. As we rode, Nils explained that Northern Lights mythology is central to the Sámi. According to their religion, life started and came down to earth through the Northern Lights.

“The white big male reindeer is holy because it came from the sky riding on the dancing aurora,” he said, his eyes never leaving the narrow asphalt road ahead which cut through the pristine white, eerily silent landscape as we forged on towards Abisko. The rare white reindeer was the source of life. And life came in spectacular fashion dancing across the skies.

In a more prosaic usage, Nils often looks to the northern lights to forecast the next day’s weather, especially when he is somewhere remote with his herd of reindeer. Because the Sámi were nomadic for centuries, they read different signs in nature so they know what type of weather was coming on their journey.

“We can see in the northern lights if strong hard winds are coming tomorrow. If they dance a lot across the sky with lots of shifting patterns, we know that strong winds are coming tomorrow,” Nils said. “If it’s a stable cloudy green aurora, then you know it’s going to be relatively stable weather tomorrow.”

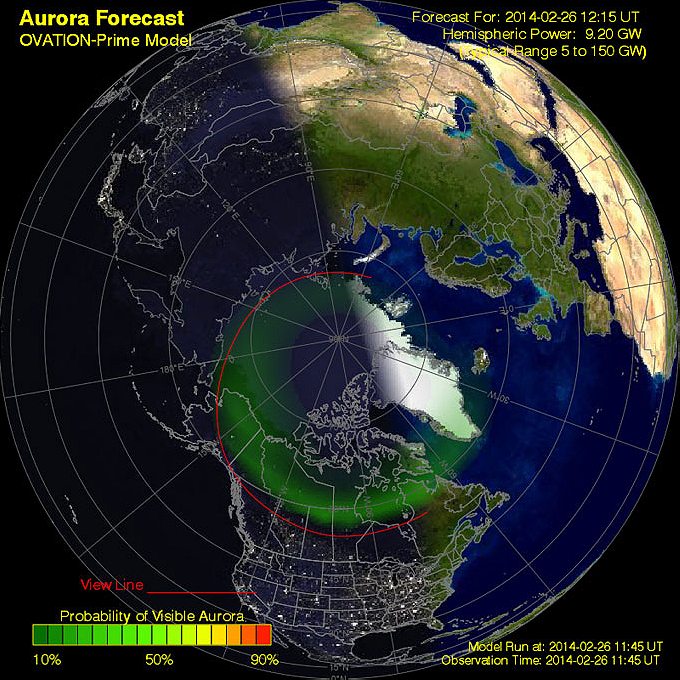

For all the closeness the Sámi feel for the lights, however, the true obsessives are the aurora chasers like Peter. It’s his livelihood: he runs evening Aurora photo courses during the peak viewing season, which runs between December and early April, in Abisko National Park and the Aurora Sky Station. The same goes for another Abisko-based photographer, Chad Blakley, who has been running photography courses for five years. And also for “astrophotographers” like Göran Strand. All these professionals rely on a dizzying array of advanced modeling. The U.S. OVATION Aurora model put out by the Space Weather Prediction Center, for example, is built on Department of Defense meteorological data collected by the ACE satellite and extrapolated by a program developed at Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Lab. It maps expected aurora appearances using measurements of Hemispheric Power ratings, space radiation classifications and something called x-ray flux.

But when you talk to these professionals, you hear, more than anything, the emotion of it all.

“I love photographing light,” says Peter, “and the dancing queen of the northern sky is certainly the most spectacular of them all.” Says Chad: “There is no natural display of beauty that can compete with the magic and splendor of the aurora borealis… There really is no better sight than a powerful aurora dancing over your head.”

Goran, the astrophotographer, grew up with the night sky. “Being out under a starry night is something I’ve done my entire life,” he says. “Every light is unique in shape, color and strength, so you never know what to expect when going out to watch it. The most intriguing thing I’ve learned after all these years, is that the Northern Lights still amaze me while watching them unfold.”

For me, standing under the frigid Abisko sky, that is the key: The shape-shifting. The way auroras morph and transform and dance so no two events are ever the same or remotely close. It holds the fascination, not just for a single nighttime, but for a lifetime of watching. It’s like a long marriage that still surprises and delights. Forget the forecasts and the data modeling. Chase the aurora and you might experience something far more elemental: love.