The city of Skopje is undergoing a Disneyfied transformation in celebration its ancient Macedonian heritage. If only the Greeks next door didn’t argue it was their history first.

“Sure it feels good when you see the movie Alexander the Great and he says ‘come on Macedonians, ride with me’,” says 23-year-old student Bojan Gazhoski, standing in Macedonia Square. “But all this is a little too much.”

Gazhoski is waiting for his girlfriend near the gigantic eight-storey “Golden Warrior” statue, which dominates the center of Skopje and forms the centerpiece of the city’s controversial new makeover called Skopje 2014.

Wagner’s Flight of the Valkyries blares from nearby speakers. Sequenced jet streams of water splash around the statue’s marble pedestal, eight bronze lions set around the fountain spew water from their mouths towards eight ancient warriors who encircle the bottom of the column.

This is more than just a garish fountain, though it is certainly that. For two decades, Greece has refused to recognize the Republic of Macedonia’s name, claiming it’s a territorial threat to its own region of the same name. They’ve saddled the country with the temporary title FYROM—Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia—and blocked its path to NATO and the EU unless they agree to a change to a name with a “clear qualifier” like ‘upper’ or ‘northern’ Macedonia.

The Greeks also accuse their northern neighbors of usurping their Hellenic culture and stealing their symbols like Alexander the Great, which they say have no connection Macedonia’s Slavic Christian majority.

THIS IS OUR WAY OF SAYING (UP YOURS) TO GREECE

Skopje 2014 is in many ways an architectural rebuttal. Although not officially named Alexander the Great, little about the Golden Warrior is subtle, especially at night when it’s illuminated by colorchanging lights. And as it stands 150m away from an equally massive statue of Alexander’s father Philip of Macedon, the message to Greece is hard to miss.

“This is our way of saying (up yours) to them,” former Macedonia foreign minister Antonio Milososki told the Guardian in an interview in 2010, as the project got underway.

Since then, Macedonia’s government has continued their construction offensive. They’ve built a barrage of 20 neoclassical and baroque inspired buildings including museums, theatres, concert halls, hotels and administrative offices as well as about 15 monuments (including a 21m Arch of Triumph) and dozens of statues. For an early visualization of the whole project, set to stirring music, see this YouTube video.

The whole thing is meant to “Europeanize” the city while instilling an official narrative about Macedonian ethnicity, identity and history, anchored deeply the idea of Macedonia’s ancient descent.

ut all this building has created a controversial, divisive and, some say, dangerous spectacle. Critics see it as inauthentic kitsch, but more problematic is the fact that its proclamation of Macedonian identity doesn’t only deliver an antagonizing message to Greece, but also to the country’s ethnic Albanians who comprise a quarter of the population.

When these critics look at the gilded fountain, they see what they say lies beneath the gaudy exterior: government corruption, dangerous ethnic-nationalism and increasing authoritarianism by a government adept at using its stalemate with Greece and festering ethnic tensions, to marshal popular support and keep social issues out of the limelight.

“This is all marketing and politics to make a point,” Gazhoski continues, as the song switches to Strauss’ Blue Danube (e). “They market history and nationalism, and people buy that.”

When I visited Skopje in May, the country had just reelected the ruling VRMO party by a convincing margin (albeit amid accusations of electoral irregularities). And I met plenty of residents who approved of the city’s new look. “These are our symbols, Alexander the Great,” says 40-year-old security guard Gore Micov, banging his chest with his fist. “When the tourists come we have something to show them, all of the history.”

Micov is standing next one of the center’s many modernist buildings, built after a devastating earthquake in 1963, that’s currently having its façade reconstructed in rococo style.

He says although he’s a proud of the project, he’s against its price tag, a common criticism in a country where 30% of people live under the poverty line., according to the CIA World Factbook. Although the admitted cost is EUR 208 million, unofficial estimates exceed EUR 500 million, both painful figures particularly when couched in accusations of shady deals.

SHOULD A GOVERNMENT BE THIS PREOCCUPIED WITH MARKETING ITS COUNTRY?

Students Angel Manova and Ana Trickovska, eating ice cream alongside the Vardar River, are more ambivalent. “Some parts are okay. Others too much,” Angela, a police cadet says, pointing at the mock galleon intruding in the river behind us. It’s one of four that will eventually house cafes.

Among their major justifications, the government and Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski (widely seen as the driver of the project) have touted the tourism appeal of the revamp and according to their figures, by 2012 foreign visitors had risen by 30% since building begun.

“It’s a bit like Las Vegas,” says 57-year-old Danish tourist Henrik Mortenson, standing on the Stone Bridge across the Vardar.

“But this country needs desperately to assert itself as a nation and from a marketing point of view it’s a splendid idea.’

But should a government be this preoccupied with marketing its country? In his recent paper Counterfeiting the Nation? Skopje 2014 and the Politics of Nation Branding, University of Virginia anthropologist Andrew Graan argues that Skopje 2014 goes beyond modern nationalism into the growing arena of brand nationalism, where states take on the role of an entrepreneurial subject to lure foreign investors and tourists.

But rather than disputing the government’s role in marketing the country, Graan explains that Skopje 2014’s critics cite lack of authenticity as their chief concern.

“The feared consequence of Skopje 2014 is that its product will render ‘Macedonia‘ a negative brand, at best recognized as kitsch, at worst recognized as essentially inauthentic and counterfeit,” he writes.

On the east side of the Vardar, the muezzin’s adhan drifts through the Old Bazaar, the heart of the Ottoman quarter of the city, home predominantly to Skopje’s ethnic Albanians–many of them Muslim.

In stark contrast to the broad avenues of the west side, here tight stone paved streets lead through archways and past mosques and Ottoman and Byzantine-era merchant houses their storefronts filled with jewelry and clothes. The maze’s aesthetic is matched by smell of Albanian and Turkish food steaming behind glass windows. Like many ethnic Albanians I speak to, salesman Taki Emin ridiculed the project.

“The first Disneyland is in the US, the second in Paris and the third is in Macedonia,” he says while hawking novelty magnets outside his clothing store. “I am Ottoman, my family came from Turkey 300 years ago. Over the river this is new history.”

Leaving an eastern instrument store nearby, ethnic Macedonian photographer, filmmaker and tambura player Gjorgji Klincaro says he’s also worried about the project’s authenticity. It elides the Yugoslav period in particular, which causes historic confusion for Macedonians, especially the younger generation.

THIS GOVERNMENT IS DELETING IMPORTANT PARTS OF OUR HISTORY

“We are Slavic people, we have a big Slavic heritage and now, out of nowhere, these ancient roots,” he says.

“You cannot make history in two years, you have to have a tradition for that. The real problem now is this government is deleting important parts of our history, the part of Communist times. The children now will be raised in totally different times, we are mixing up our heads with different history.”

According to a 2013 study by Skopje’s Institute of Social Science and Humanities, only 5.8 percent of the country’s populations consider the period of antiquity of defining importance to Macedonia’s identity, a number which rises to 7.8 percent among ethnic Macedonians.

Meanwhile, almost 20% cited the medieval period of Orthodox Slavic Christianity as the defining period, while 20 percent chose Macedonia’s Independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, 16.9 percent said the Yugoslav period and 13.8 percent the turn of the 20th century struggle for Macedonian liberation from the Ottoman Empire.

“It’s not just an architectural project but is also a cultural project, a sort of social engineering,” says Artan Sadiku, director of Skopje’s Institute of Social Sciences and Humanities, sitting on the balcony of the institute 15 minutes walk from the center.

Sporting a gruff beard and checked shirt, Sadiku chain-smokes Gauloise Blondes and talks with frustration about the rapid transformation of the city.

He says that while cracking down on freedom of speech and the media, the government began injecting references to Macedonia’s ancient history in public discourse and text books, as a way of building a nationalistic argument against Greece and even against the ethnic Albanians in Macedonia.

“Even a significant portion of those working with income are poor,” he says. “[The government] knew the social situation in the country will not be stable for long so they had to switch from economic argument to mainstreaming the ultra-nationalist argument, and started to use internal and external enemies.”

“What you do is unite the country under a big national rhetoric and then you make it impossible for social issues to become primary political issues.”

“The main political issue in these last five years is the defending of national identity, the defending of the name. I think without the increased pressure from Greek side, without their veto [of] the country’s integration into the EU, the fascination with Alexander the Great would have remained as it always was, a very marginal part of society.”

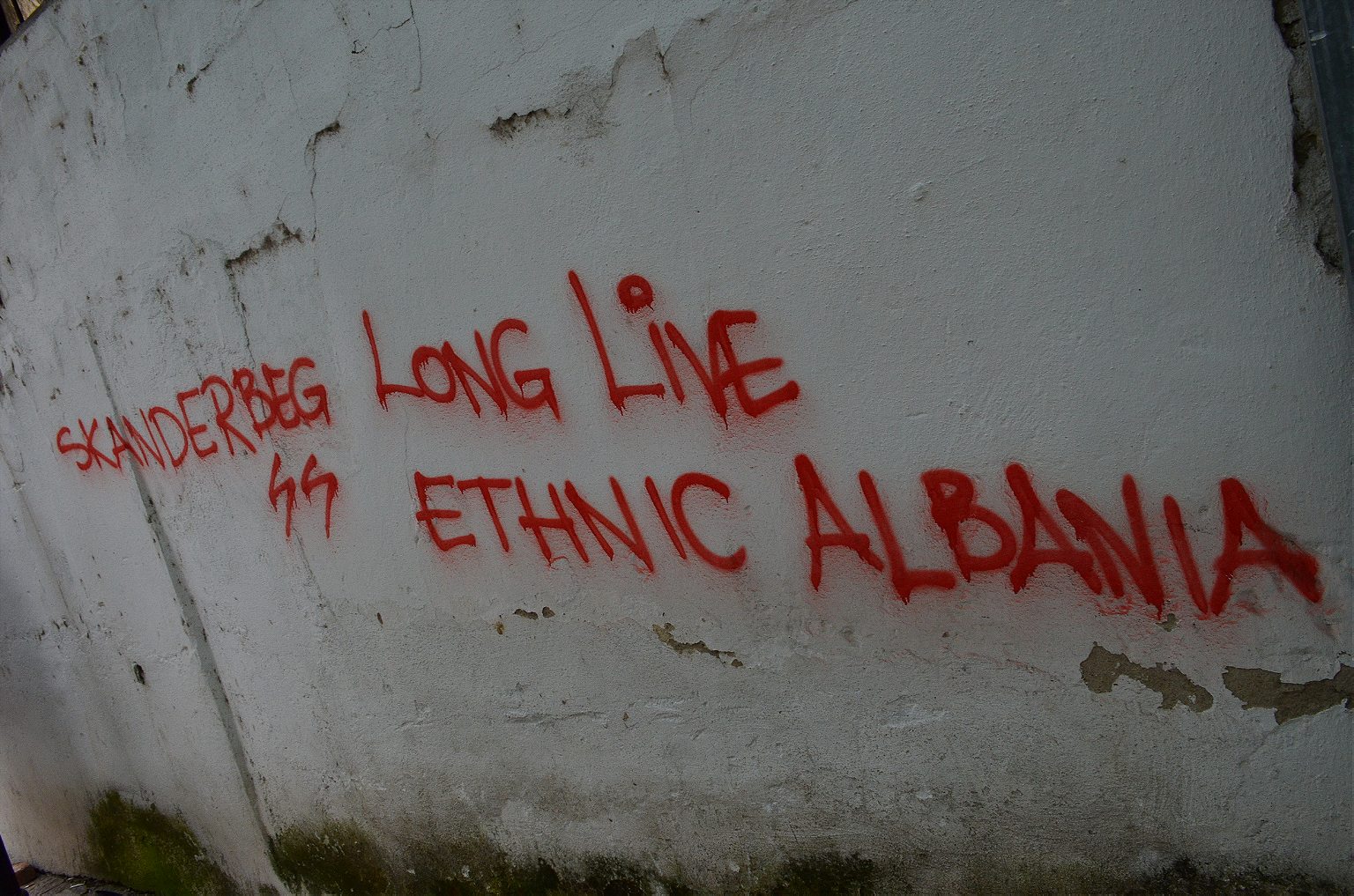

Since nearly slipping into civil war in 2001, the country has seen sporadic clashes between ethnic Albanians and ethnic Macedonians, often involving youths on the streets or in buses—the most recent clashes took place July 4, as Albanian protesters and police battled in the capital.

Initially promoted as a unifying project, Skopje 2014’s exclusion of Albanian and Muslim monuments has only exacerbated tensions. In December last year, ethnic Albanians attacked a statue of 14th century Serbian Tzar Dusan that was built on central Skopje’s Bridge of Civilizations. Although celebrated by Serbians as a great ruler who expanded the Serb medieval kingdom to its peak, Dusan is seen by Albanians as an occupier who annexed traditionally Albanian regions.

“If you look at the [new] buildings around the river you will notice you cannot see anything behind them, none of the old, oriental side of Skopje, especially the mosques,” says Arsim Zekolli, former Macedonian ambassador to OSCE and now a leading Macedonian-language columnist.

“It’s considered a wall of division that aims to separate the Macedonian part of town from the Albanian part.”

Although VMRO shares power with an ethnic Albanian party, the ethnic groups’ public and private lives are largely divided, a gap politicians on both sides maintain as a distraction to their mutual interests of corruption says Zekolli.

WE HAVE A DECLINE IN EVERY FACET OF DEMOCRACY

He says that while purporting to Europeanize the city, the country’s leaders are dragging Macedonia in the opposite direction, under the noses of tourists and without any objection from the West. Instead of condemning rife corruption and organized crime, the international community tolerates it for the sake of regional stability, he says.

“During this dispute with Greece we have a simultaneous decline in every facet of democracy, it’s obvious it’s being used as an excuse to crackdown on the opposition, on journalists, NGOs and the international community, all under the blanket of justification that this is because Greece is blocking us.”

“We are losing contact with Europe, becoming less and less a European country and turning into a version of democracy like Turkey or Russia.”

Before leaving Skopje, I climb the Kale Fortress, first built in the six century. Regardless of one’s thoughts on Skopje’s new look; the surrounding beauty of the mountains, including Vodno, to the southwest, with its massive 66m-tall Millennium Cross, is hard to dispute. From above, the city itself looks calm, its strange mix of architecture, monuments, statues and mosques all bathed in the soft late afternoon light.

And yet later that day, around the time my bus was approaching the border with Bulgaria, ethnic rioting had broken out in Skopje. An Albanian teen had supposedly stabbed a Macedonian teen, and in response hundreds of ethnic Macedonian rioters were smashing shops and cars they thought belonged to ethnic Albanians.

It wasn’t a direct response to the violence, perhaps, but three weeks later, the government announced more upgrades for Macedonia Square. First on the agenda: a 10 by 20 meter “jumping jet” fountain for the space in front of Alexander.